Antidepressant Drugs: Additional Clinical Uses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Migraine Agents Reference Number: OH.PHAR.PPA.34 Effective Date: 01.01.21 Last Review Date: 11.20 Line of Business: Medicaid

Clinical Policy: Anti-Migraine Agents Reference Number: OH.PHAR.PPA.34 Effective Date: 01.01.21 Last Review Date: 11.20 Line of Business: Medicaid See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description • When using a preferred agent where applicable, the number of tablets/doses allowed per month will be restricted based on the manufacturer’s package insert and/or Buckeye Health plans quantity limits. CNS AGENTS: ANTI-MIGRAINE AGENTS – ACUTE MIGRANE TREATMENT NO PA REQUIRED “PREFERRED” STEP THERAPY REQUIRED PA REQUIRED “NON-PREFERRED” “PREFERRED” NARATRIPTAN (GENERIC OF AMERGE®) NURTEC™ ODT (rimegepant) ALMOTRIPTAN (generic of Axert®) RIZATRIPTAN TABLETS (GENERIC OF CAFERGOT® (ergotamine w/caffeine) MAXALT®) ELETRIPTAN (generic of Relpax®) RIZATRIPTAN ODT (GENERIC OF ERGOMAR® (ergotamine) MAXALT-MLT®) FROVA® (frovatriptan) SUMATRIPTAN TABLETS, NASAL SPRAY, MIGERGOT® (ergotamine w/caffeine) INJECTION (GENERIC OF MIGRANAL® (dihydroergotamine) IMITREX®) ONZETRA™ XSAIL™ (sumatriptan) REYVOW™ (lasmiditan) SUMAVEL DOSEPRO® (sumatriptan) TOSYMRA® (sumatriptan) TREXIMET® (sumatriptan/naproxen) UBRELVY™ (ubrogepant)* ZOLMITRIPTAN (generic of Zomig®) ZOLMITRIPTAN ODT (generic of Zomig ZMT®) ZOMIG® NASAL SPRAY (zolmitriptan) CNS AGENTS: ANTI-MIGRAINE AGENTS – CLUSTER HEADACHE TREATMENT NO PA REQUIRED “PREFERRED” PA REQUIRED “NON-PREFERRED” VERAPAMIL (Generic of Calan®) EMGALITY™ (galcanezumab) VERAPAMIL SR/ER (Generic of Calan SR®, Isoptin SR®, Verelan®) CNS AGENTS: ANTI-MIGRAINE AGENTS – PROPHYLAXIS TREATMENT NO PA REQUIRED “PREFERRED” STEP THERAPY REQUIRED PA REQUIRED “NON-PREFERRED” (Trials of at least 3 controller “PREFERRED” medications) Cardiovascular Agents: Beta-blockers AIMOVIG™ (erenumab-aooe) † EMGALITY™ (galcanezumab) CNS Agents: Anticonvulsants AJOVY™ (fremanezumab-vfrm) * CNS Agents: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors CNS Agents: Tricyclic antidepressants †Initial Dose is limited to 70mg once monthly; may request dose increase if 70mg fails to provide adequate relief over two consecutive months. -

Supporting Children with Autism with Bedwetting Difficulties

Supporting Children with Autism with Bedwetting Difficulties (Primary Nocturnal Enuresis) Bedwetting is described as involuntary wetting during sleep, and is a common occurrence in childhood. Ten per cent of 7 year olds are affected by bedwetting. Boys are affected more than girls, and there is often a family history. Bedwetting often improves with age. There is a higher incidence of bedwetting in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Bedwetting can occur as a result of one or more of the following reasons: 1. Bladder control has not yet matured 2. Sleeping deeply and not waking in response to a full bladder 3. Producing a lot of urine at night due to hormonal reasons 4. Overactive bladder (by day and by night) Recommendations Avoid any punishment for bedwetting. Anxiety or significant socialisation difficulties can affect bedwetting. Focus on these first before addressing bedwetting. Children with ASD often have sleep difficulties. Any approaches to help bedwetting should not affect sleep. Strategies Use social stories and visual schedules to support your child. Examples include; a schedule of their bedtime routine that may include two trips to the toilet (see below), and social stories about what to do if their bed is wet when they wake during the night or in the morning. Set realistic and appropriate targets, and reward your child for achieving them. Rewarding a dry night may be unachievable initially and may result in disappointment for your child. An example of an achievable target may be; putting a used pull up in the bin, or helping to change the sheets. Empty bladder at night-time as part of bedtime routine. -

Medication: Amitriptyline 10 Mg

Amitriptyline (Elavil) COMPLEX CHRONIC DISEASES PROGRAM Medication Handout Date: May 15, 2018 Medication: Amitriptyline 10 mg What is Amitriptyline? Amitriptyline belongs to a group of medications called tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) that were first used to treat depression. It works by altering the levels of certain neuro- transmitters in the brain such as noradrenalin and serotonin. They have since been found to be effective for many different uses such as: pain, helping with sleep quality (but is not a sleeping pill), irritable bowel syndrome (with diarrhea), migraine prevention, and interstitial cystitis. Expected Benefit: Usually takes several weeks to notice a benefit You may not notice a benefit until you get to a dose of 25 mg Watch for possible side effects: This list of side effects is important for you to be aware of; however, it is also important to remember that not all side effects happen to all people. Many of these less serious side effects will improve over the first few days of taking the medications. If you have problems with these side effects talk with your doctor or pharmacist: Dry mouth – this is the most common side; the others are much less frequent Hangover effect – too sleepy in the morning Blurred vision Urinary retention, trouble with urination Tiredness, dizziness that is more than usual Diarrhea or constipation Stopping the medication: Do NOT stop taking this medication suddenly without asking your doctor – this medication is usually decreased slowly (at higher doses) before it is stopped completely How to use this medication: Take this medication with or without food Dosing Schedule: Start with 5 mg (½ tablet) 2 hrs before bed Increase dose according to table below Many patients can only tolerate 20 or 30 mg If you don’t have dry mouth or side effects, you can continue slowly increasing the dose to a maximum of 70 mg You can stay at a lower dose (stop increasing) if you get side effects (usually dry mouth). -

Clomipramine | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION Clomipramine This information from Lexicomp® explains what you need to know about this medication, including what it’s used for, how to take it, its side effects, and when to call your healthcare provider. Brand Names: US Anafranil Brand Names: Canada Anafranil; MED ClomiPRAMINE; TARO-Clomipramine Warning Drugs like this one have raised the chance of suicidal thoughts or actions in children and young adults. The risk may be greater in people who have had these thoughts or actions in the past. All people who take this drug need to be watched closely. Call the doctor right away if signs like low mood (depression), nervousness, restlessness, grouchiness, panic attacks, or changes in mood or actions are new or worse. Call the doctor right away if any thoughts or actions of suicide occur. This drug is not approved for use in all children. Talk with the doctor to be sure that this drug is right for your child. What is this drug used for? It is used to treat obsessive-compulsive problems. It may be given to you for other reasons. Talk with the doctor. Clomipramine 1/8 What do I need to tell my doctor BEFORE I take this drug? If you have an allergy to clomipramine or any other part of this drug. If you are allergic to this drug; any part of this drug; or any other drugs, foods, or substances. Tell your doctor about the allergy and what signs you had. If you have had a recent heart attack. If you are taking any of these drugs: Linezolid or methylene blue. -

Current Current

CP_0406_Cases.final 3/17/06 2:57 PM Page 67 Current p SYCHIATRY CASES THAT TEST YOUR SKILLS Chronic enuresis has destroyed 12-year-old Jimmy’s emotional and social functioning. The challenge: restore his self-esteem by finding out why can’t he stop wetting his bed. The boy who longed for a ‘dry spell’ Tanvir Singh, MD Kristi Williams, MD Fellow, child® Dowdenpsychiatry ResidencyHealth training Media director, psychiatry Medical University of Ohio, Toledo CopyrightFor personal use only HISTORY ‘I CAN’T FACE MYSELF’ during regular checkups and refer to a psychia- immy, age 12, is referred to us by his pediatri- trist only if the child has an emotional problem J cian, who is concerned about his “frequent secondary to enuresis or a comorbid psychiatric nighttime accidents.” His parents report that he wets disorder. his bed 5 to 6 times weekly and has never stayed con- Once identified, enuresis requires a thorough sistently dry for more than a few days. assessment—including its emotional conse- The accidents occur only at night, his parents quences, which for Jimmy are significant. In its say. Numerous interventions have failed, including practice parameter for treating enuresis, the restricting fluids after dinner and awakening the boy American Academy of Child and Adolescent overnight to make him go to the bathroom. Psychiatry (AACAP)1 suggests that you: Jimmy, a sixth-grader, wonders if he will ever Take an extensive developmental and family stop wetting his bed. He refuses to go to summer history. Find out if the child was toilet trained and camp or stay overnight at a friend’s house, fearful started walking, talking, or running at an appro- that other kids will make fun of him after an acci- priate age. -

Medication Conversion Chart

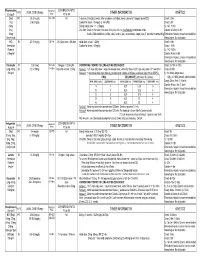

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

Cyproheptadine

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION Cyproheptadine This information from Lexicomp® explains what you need to know about this medication, including what it’s used for, how to take it, its side effects, and when to call your healthcare provider. What is this drug used for? It is used to ease allergy signs. It is used to treat hives. It may be given to you for other reasons. Talk with the doctor. What do I need to tell my doctor BEFORE I take this drug? For all patients taking this drug: If you have an allergy to cyproheptadine or any other part of this drug. If you are allergic to this drug; any part of this drug; or any other drugs, foods, or substances. Tell your doctor about the allergy and what signs you had. If you have any of these health problems: Bowel block, enlarged prostate, glaucoma, trouble passing urine, or ulcers in your stomach or bowel. If you are taking certain drugs used for depression like Cyproheptadine 1/9 isocarboxazid, phenelzine, or tranylcypromine, or drugs used for Parkinson’s disease like selegiline or rasagiline. If you are taking any of these drugs: Linezolid or methylene blue. If you are 65 or older. If you are breast-feeding. Do not breast-feed while you take this drug. Children: If your child is a premature baby or is a newborn. Do not give this drug to a premature baby or a newborn. This is not a list of all drugs or health problems that interact with this drug. Tell your doctor and pharmacist about all of your drugs (prescription or OTC, natural products, vitamins) and health problems. -

FDA Approved Drugs with Broad Anti-Coronaviral Activity Inhibit SARS-Cov-2 in Vitro

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.25.008482; this version posted March 27, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. FDA approved drugs with broad anti-coronaviral activity inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro Stuart Weston1, Rob Haupt1, James Logue1, Krystal Matthews1 and Matthew B. Frieman*1 1 - Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 685 W. Baltimore St., Room 380, Baltimore, MD, 21201, USA *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Key words: SARS-CoV-2, nCoV-2019, COVID-19, drug repurposing, FDA approved drugs, antiviral therapeutics, pandemic, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine AbstraCt SARS-CoV-2 emerged in China at the end of 2019 and has rapidly become a pandemic with over 400,000 recorded COVID-19 cases and greater than 19,000 recorded deaths by March 24th, 2020 (www.WHO.org) (1). There are no FDA approved antivirals or vaccines for any coronavirus, including SARS-CoV-2 (2). Current treatments for COVID-19 are limited to supportive therapies and off-label use of FDA approved drugs (3). Rapid development and human testing of potential antivirals is greatly needed. A potentially quicker way to test compounds with antiviral activity is through drug re-purposing (2, 4). Numerous drugs are already approved for use in humans and subsequently there is a good understanding of their safety profiles and potential side effects, making them easier to test in COVID-19 patients. -

NORPRAMIN® (Desipramine Hydrochloride Tablets USP)

NORPRAMIN® (desipramine hydrochloride tablets USP) Suicidality and Antidepressant Drugs Antidepressants increased the risk compared to placebo of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies of major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Anyone considering the use of NORPRAMIN or any other antidepressant in a child, adolescent, or young adult must balance this risk with the clinical need. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction in risk with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older. Depression and certain other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide. Patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber. NORPRAMIN is not approved for use in pediatric patients. (See WARNINGS: Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk, PRECAUTIONS: Information for Patients, and PRECAUTIONS: Pediatric Use.) DESCRIPTION NORPRAMIN® (desipramine hydrochloride USP) is an antidepressant drug of the tricyclic type, and is chemically: 5H-Dibenz[bƒ]azepine-5-propanamine,10,11-dihydro-N-methyl-, monohydrochloride. 1 Reference ID: 3536021 Inactive Ingredients The following inactive ingredients are contained in all dosage strengths: acacia, calcium carbonate, corn starch, D&C Red No. 30 and D&C Yellow No. 10 (except 10 mg and 150 mg), FD&C Blue No. 1 (except 25 mg, 75 mg, and 100 mg), hydrogenated soy oil, iron oxide, light mineral oil, magnesium stearate, mannitol, polyethylene glycol 8000, pregelatinized corn starch, sodium benzoate (except 150 mg), sucrose, talc, titanium dioxide, and other ingredients. -

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH ELAVIL® Amitriptyline Hydrochloride Tablets

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH ELAVIL® amitriptyline hydrochloride tablets USP 10, 25, 50 and 75 mg Antidepressant AA PHARMA INC. DATE OF PREPARATION: 1165 Creditstone Road Unit #1 August 29, 2018 Vaughan, ON L4K 4N7 Control No.: 217626 1 PRODUCT MONOGRAPH ELAVIL® amitriptyline hydrochloride tablets USP 10, 25, 50, 75 mg THERAPEUTIC CLASSIFICATION Antidepressant ACTIONS AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Amitriptyline hydrochloride is a tricyclic antidepressant with sedative properties. Its mechanism of action in man is not known. Amitriptyline inhibits the membrane pump mechanism responsible for the re-uptake of transmitter amines, such as norepinephrine and serotonin, thereby increasing their concentration at the synaptic clefts of the brain. Amitriptyline has pronounced anticholinergic properties and produces EKG changes and quinidine-like effects on the heart (See ADVERSE REACTIONS). It also lowers the convulsive threshold and causes alterations in EEG and sleep patterns. Orally administered amitriptyline is readily absorbed and rapidly metabolized. Steady-state plasma concentrations vary widely and this variation may be genetically determined. Amitriptyline is primarily excreted in the urine, mostly in the form of metabolites, with some excretion also occurring in the feces. INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ELAVIL® (amitriptyline hydrochloride) is indicated in the drug management of depressive illness. ELAVIL® may be used in depressive illness of psychotic or endogenous nature and in selected patients with neurotic depression. Endogenous depression is more likely to be alleviated than are other depressive states. ELAVIL® ®, because of its sedative action, is also of value in alleviating the anxiety component of depression. As with other tricyclic antidepressants, ELAVIL® may precipitate hypomanic episodes in patients with bipolar depression. These drugs are not indicated in mild depressive states and depressive reactions. -

Neuroprotection by Chlorpromazine and Promethazine in Severe Transient and Permanent Ischemic Stroke

Mol Neurobiol (2017) 54:8140–8150 DOI 10.1007/s12035-016-0280-x Neuroprotection by Chlorpromazine and Promethazine in Severe Transient and Permanent Ischemic Stroke Xiaokun Geng1,2 & Fengwu Li1 & James Yip2 & Changya Peng2 & Omar Elmadhoun2 & Jiamei Shen1 & Xunming Ji1,3 & Yuchuan Ding1,2 Received: 29 June 2016 /Accepted: 31 October 2016 /Published online: 28 November 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Previous studies have demonstrated depressive or enhance C + P-induced neuroprotection. C + P therapy im- hibernation-like roles of phenothiazine neuroleptics [com- proved brain metabolism as determined by increased ATP bined chlorpromazine and promethazine (C + P)] in brain levels and NADH activity, as well as decreased ROS produc- activity. This ischemic stroke study aimed to establish neuro- tion. These therapeutic effects were associated with alterations protection by reducing oxidative stress and improving brain in PKC-δ and Akt protein expression. C + P treatments con- metabolism with post-ischemic C + P administration. ferred neuroprotection in severe stroke models by suppressing Sprague-Dawley rats were subjected to transient (2 or 4 h) the damaging cascade of metabolic events, most likely inde- middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) followed by 6 or pendent of drug-induced hypothermia. These findings further 24 h reperfusion, or permanent (28 h) MCAO without reper- prove the clinical potential for C + P treatment and may direct fusion. At 2 h after ischemia onset, rats received either an us closer towards the development of an efficacious neuropro- intraperitoneal (IP) injection of saline or two doses of C + P. tective therapy. Body temperatures, brain infarct volumes, and neurological deficits were examined. -

A Drug Repositioning Approach Identifies Tricyclic Antidepressants As Inhibitors of Small Cell Lung Cancer and Other Neuroendocrine Tumors

Published OnlineFirst September 26, 2013; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0183 RESEARCH ARTICLE A Drug Repositioning Approach Identifi es Tricyclic Antidepressants as Inhibitors of Small Cell Lung Cancer and Other Neuroendocrine Tumors Nadine S. Jahchan 1 , 2 , Joel T. Dudley 1 , Pawel K. Mazur 1 , 2 , Natasha Flores 1 , 2 , Dian Yang 1 , 2 , Alec Palmerton 1 , 2 , Anne-Flore Zmoos 1 , 2 , Dedeepya Vaka 1 , 2 , Kim Q.T. Tran 1 , 2 , Margaret Zhou 1 , 2 , Karolina Krasinska 3 , Jonathan W. Riess 4 , Joel W. Neal 5 , Purvesh Khatri 1 , 2 , Kwon S. Park 1 , 2 , Atul J. Butte 1 , 2 , and Julien Sage 1 , 2 Downloaded from cancerdiscovery.aacrjournals.org on September 29, 2021. © 2013 American Association for Cancer Research. Published OnlineFirst September 26, 2013; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0183 ABSTRACT Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine subtype of lung cancer with high mortality. We used a systematic drug repositioning bioinformat- ics approach querying a large compendium of gene expression profi les to identify candidate U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs to treat SCLC. We found that tricyclic antidepressants and related molecules potently induce apoptosis in both chemonaïve and chemoresistant SCLC cells in culture, in mouse and human SCLC tumors transplanted into immunocompromised mice, and in endog- enous tumors from a mouse model for human SCLC. The candidate drugs activate stress pathways and induce cell death in SCLC cells, at least in part by disrupting autocrine survival signals involving neurotransmitters and their G protein–coupled receptors. The candidate drugs inhibit the growth of other neuroendocrine tumors, including pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma.