The Relationship Between Political Elites and Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Fear and Faith: Uncertainty, Misfortune and Spiritual Insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Ligtvoet, I.J.G.C

Fear and faith: uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Ligtvoet, I.J.G.C. Citation Ligtvoet, I. J. G. C. (2011). Fear and faith: uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria. s.l.: s.n. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/22696 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/22696 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Fear and Faith Uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Inge Ligtvoet MA Thesis Supervision: ResMA African Studies Dr. Benjamin Soares Leiden University Prof. Mirjam de Bruijn August 2011 Dr. Oka Obono Dedicated to Reinout Lever † Hoe kan de Afrikaanse zon jouw lichaam nog verwarmen en hoe koelt haar regen je af na een tropische dag? Hoe kan het rode zand jouw voeten nog omarmen als jij niet meer op deze wereld leven mag? 1 Acknowledgements From the exciting social journey in Nigeria that marked the first part of this work to the long and rather lonely path of the final months of writing, many people have challenged, advised, heard and answered me. I have to thank you all! First of all I want to thank Dr. Benjamin Soares, for being the first to believe in my fieldwork plans in Nigeria and for giving me the opportunity to explore this fascinating country. His advice and comments in the final months of the writing have been really encouraging. I’m also grateful for the supervision of Prof. Mirjam de Bruijn. From the moment she got involved in this project she inspired me with her enthusiasm and challenged me with critical questions. -

Resource Allocation and the Problem of Utilization in Nigeria: an Analysis of Resource Utilization in Cross River State, 1999-2007

Resource Allocation and the Problem of Utilization in Nigeria: An Analysis of Resource Utilization in Cross River State, 1999-2007 By ATELHE, GEORGE ATELHE Ph. D/SOC-SCI/02799/2006-2007 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POST- GRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE. JANUARY, 2013 1 DEDICATION This research is dedicated to the Almighty God for His faithfulness and mercy. And to all my teachers who have made me what I am. 2 DELARATION I, Atelhe George Atelhe hereby declare, that this Dissertation has been prepared and written by me and it is the product of my own research. It has not been accepted for any degree elsewhere. All quotations have been indicated by quotation marks or by indentation and acknowledged by means of bibliography. __________________ ____________ Atelhe, George Atelhe Signature/Date 3 CERTIFICATION This Dissertation titled ‘Resource Allocation and the Problem of Utilization in Nigeria: An Analysis of Resource Utilization in Cross River State, 1999-2007’ meets the regulation governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) of Ahmadu Bello University, and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. ____________________________ ________________ Dr. Kayode Omojuwa Date Chairman, Supervisory Committee ____________________________ ________________ Dr. Umar Mohammed Kao’je Date Member, Supervisory Committee ___________________________ ________________ Prof. R. Ayo Dunmoye Date Member, Supervisory Committee ___________________________ ________________ Dr. Hudu Abdullahi Ayuba Date Head of Department ___________________________ ________________ Dean, School of Post-Graduate Studies Date 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Words are indeed inadequate to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors, Dr Kayode Omojuwa, Dr Umar Kao’je, and Prof R.A. -

University of Maiduguri Utme Admission

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR) UTME ADMISSION FOR 2017/2018 ACADEMIC SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE AND SURGERY S/No. Reg. No Name of Candidate 1 76186593GA MUHAMMED MUSABIRA MBBS 2 75616150BI ALI JUMMA'A SA'ADATU MUHAMMAD MBBS 3 75225603JD BELLO MAHASIN MBBS 4 75228686FJ TOGBORESO LOKPANE JAVAV MBBS 5 75234576ED BRUNO O CLEMS MBBS 6 75853832BJ ADEKOYA SEUN MBBS 7 76074976GH HASANA J DANIEL MBBS 8 75072297DH PIUS PAULINUS WARIGASU MBBS 9 75922039GI ABU OLUWAFEMI SUCCESS MBBS 10 75226335DB OLADOSU ABDULRASAQ OLALEKAN MBBS 11 76772693HJ CHARLES ANIYIN MBBS 12 75071512GE NEHEMIAH NGATI ULEA MBBS 13 75596581EA YUNUSA UMAR MBBS 14 77174029DF YUNUSA SHAMSI MBBS 15 75232914IC SHALTUT AHMAD MUHAMMAD MBBS 16 75962393GC GBOGBO JOSEPH OGHENEOCHUKO MBBS 17 76169985CG AMBI YAHAYA SALEH MBBS 18 75343406FF TOBALU FELIX AIGBOKHAI MBBS 19 75230208FC TUMBA CHRISTOPHER SUNDAY MBBS 20 75231817HF PHILIP PRISCILLIA DIBAL MBBS 21 75223796IC OLUKUNLE BOLANLE IRETUNDE MBBS 22 75966302HC UMEH FORTUNE CHIMA MBBS 23 76055844DJ ABASS ABDULLATEEF RAJI MBBS 24 76770023DI UDECHUKWU PROMISE CHIDI MBBS Page 1 of 144 25 75069790IJ JESSE TAIMAKO MBBS 26 75356959DJ ONOJA ANTHONY MATHEW MBBS 27 75475076CJ MUHAMMAD ABBAS BELLO MBBS 28 75225451GE NGGADA SAMUEL DAVID MBBS 29 76770533GA HARUNA ABUBAKAR YIRASO MBBS 30 75229251BD ABDU YUSUF LAWAN MBBS 31 76187405EJ YUSUF FATIMAZARA WASILI MBBS 32 77084690EB OZIGI PIUS JOHN ASUKU MBBS 33 75482315EA MUSA ILIYA MBBS 34 75550189CB TITUS FRIDAY MBBS 35 75174715HJ UMORU HARUNA MAINA MBBS -

Carnival Fiesta and Socio-Economic Development of Calabar Metropolis, Nigeria F

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 2 Issue 6 ǁ June. 2013ǁ PP.33-41 Carnival Fiesta and Socio-economic development of Calabar Metropolis, Nigeria F. M. Attah1, Agba, A. M. Ogaboh2 and Festus Nkpoyen3 1Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. 2(corresponding author) is also a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. 3Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Purpose- This study examines the relationship between Calabar carnival fiesta and the socio- economic development of Calabar metropolis in Cross River State, Nigeria. Design/methodology/approach- The approach adopted in this study was survey method which employed structured questionnaires,which were administered to 1495 respondents. Data elicited from respondents were analyzed using simple percentage and Pearson product moment correlation. Findings - The study reveals that Calabar carnival fiesta significantly influence the development of infrastructural facilities, level of poverty, standard of living of the people in terms of clean and healthy environment and the sexual behaviour of the people in Calabar Metropolis. Practical implications –Some of the recommendations are, that, a blue print on Calabar carnival fiesta be expanded to include other parts of Cross River State. Originality/value- This research work is the first empirical work to assess the impact of Calabar carnival fiesta on the socio-economic development of Calabar Metropolis. Empirical evidence from the field provides an insight that could assist in redesigning tourism blue print in Cross River State. -

Federal Republic of Nigeria - Official Gazette

Federal Republic of Nigeria - Official Gazette .. Nov i2. - . - Lagos ~ 25th February, 1988 Vol. 75 CONTENTS oO Lo Page Appointment of Judges vs ve ae se ee +. ee ee oe 180-82 Movements of Officers .. we ae ee 182-216 “Individual Duty Drawback Rate sppicoved andex fitedity Duty Drawback Committee. _ . -- 216 Public Notice No. 11—Cooper Drums Nigeria Limited—Appointment of Receiver/Manager ee 216 Public NoticeNo. 12—Suit No. M/705/87 we lee +. os ae 217 - 180 | OFFICIAL GAZETTE Nov 42, Vol. 75 Government Notice No. 98 . _ APPOINTMENT OFk JUDGES. The..f6Tlorwineea. cers were appointed to Le Supreme Court of Nigeria, Court of Appeal, FedeavastCourt, States‘High,Court, Sharia Court of Appeal.and the CustomaryCourt of Appeal res- it is —_ , : . fp. J4PeNaingsAy : - s1489ul Court: ' : . Effective Date Justice BoonyaminGladirin Kazeem .. Supreme Cpurt of Nigeria ve e 5~7-84 justite Dahunsi OlubeinniCoker .. Supreme Courtof Nigeria ee - 5~7-84 Justice Adbiphus Godwin Karibi-Whyte Supreme Court of Nigeria ce we . 5-784 Justice Saidu Kawu o .. Supreme Court of Nigeria an a oe 5-7-84 Justice Chukwudifu Akune Oputa .. Supreme Court of Nigeria ae wee 5-7-84 Justice Salihu Moddibo Alfa Belgore .. Supreme Court of Nigeria. oe ees ee | 26-86-84 justice Owolabi Kolawole .., we .. Courtof Appeal .. 0... et cee. 1-5-85 . -Justice Joseph Diekola Ogundere ... .. CourtofAppeal .. ee ae ee 1=5-85 | Justice Reider Joe Jacks .. Court of Appeal -. _ 1-5-85 Justice Mahamud Babatunde Belgore .. Acting Chic?Judge of Federal High Cou ‘s. 22-10-84 Justice Danlami Mohanimed . .. -Feéderal High Court . -

Boko Haram, Nigeria Has a Chance to Move Toward Reconciliation and Durable Peace

i n s t i t u t e f o r i n t e g r at e d t r a n s i t i o n s The Limits of Punishment Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism nigeria case study Vanda Felbab-Brown May, 2018 “In Nigeria, We Don’t Want Them Back” Amnesty, Defectors’ Programs, Leniency Measures, Informal Reconciliation, and Punitive Responses to Boko Haram About the Author Dr. Vanda Felbab-Brown is a senior fellow in the Acknowledgements Foreign Policy program at the Brookings Institu- I would like to thank Frederic Eno of the United tion in Washington, DC. She is an expert on inter- Nations in Nigeria for facilitating my research. national and internal conflicts and nontraditional The help of Adeniyi Oluwatosin, Nuhu Ndahi, and security threats, including insurgency, organized Philip Olayoku was invaluable in the research. crime, urban violence, and illicit economies. Her Many thanks go to all of my interlocutors for fieldwork and research have covered, among their willingness to engage. Particularly for my others, Afghanistan, South and Southeast Asia, Nigerian interlocutors, such willingness could the Andean region, Mexico, Morocco, and Eastern entail risks to their personal safety or jeopardise and Western Africa. Dr. Felbab-Brown is the their job security or economic livelihoods from author of The Extinction Market: Wildlife Traffick- the hands of Boko Haram or militias and Nigerian ing and How to Counter It (Hurst-Oxford 2017); officials. I am thus most grateful to those who Narco Noir: Mexico’s Cartels, Cops, and Corruption accepted such risks and were very willing to (Brookings Institution Press, 2019, forthcom- provide accurate and complete information. -

Calabar Municipal Recreation Centre Expression Of

CALABAR MUNICIPAL RECREATION CENTRE EXPRESSION OF INDIGENOUS CONTEXT IN RECREATIONAL FACILITY DESIGN BY EkpaAyahambemNtan DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA MAY 2014 1 CALABAR MUNICIPAL RECREATION CENTRE EXPRESSION OF INDIGENOUS CONTEXT IN RECREATIONAL FACILITY DESIGN BY EkpaAyahambemNtan B.sc Arch (ABU 2007) M.sc/ENV-DESIGN/01787/2006–2007 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN ARCHITECTURE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA MAY 2014. 2 DECLARATION I declare that the work in the dissertation entitled „CALABAR MUNICIPAL RECREATION CENTRE EXPRESSION OF INDIGENOUS CONTEXT, IN RECREATIONAL FACILITY DESIGN‟ has been performed by me in the Department of Architecture under the supervision of Dr. S. N Oluigbo and Dr. A. Ango The information derived from the literature has duly been acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided. No part of this dissertation was previously presented for another degree or diploma at any university. EkpaAyahambemNtan May, 2014 Name of student Signature Date 3 CERTIFICATION This dissertation entitled “CALABAR MUNICIPAL RECREATION CENTRE EXPRESSION OF INDIGENOUS CONTEXT, IN RECREATIONAL FACILITY DESIGN” by Ekpa .A. Ntan, meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Master of Science of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. _____________________________ ________________ Dr S. N. Oluigbo Date Chairman, Supervisory Committee _____________________________ ________________ Dr. A. Ango Date Member, Supervisory Committee __________________________ __________________ Dr. M.L. Sagada Date Member, Supervisory Committee _____________________________ ________________ Arc. -

List of Issues and Questions in Relation to the Combined Seventh and Eighth Periodic Reports of Nigeria

CEDAW/C/NGA/Q/7-8/Add.1 Distr.: General 27 June 2017 Original: English ADVANCE UNEDITED VERSION Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Sixty-seventh session 3-21 July 2017 Item 4 of the provisional agenda Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women List of issues and questions in relation to the combined seventh and eighth periodic reports of Nigeria Addendum Replies of Nigeria* [Date received: 27 June 2017] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. Note: The present document is being issued in English, French and Spanish only. CEDAW/C/NGA/Q/7-8/Add.1 Constitutional and legislative framework and harmonization of laws 1. Issue: Response 1. During the constitutional review process, the gender ministry submitted a memo to the Review Committee on the need to amend Section 26(2)(a) of the 1999 Constitution such as to give foreign men married to Nigerians the opportunity to acquire citizenship. Further is the need to state in express terms that a woman married to any man from a state of the federation other than her own should have the rights to choose which of the states to claim as her own. 2. Further suggested an amendment to Section 147(3) of the constitution, which provides for federal character in the president’s selection of ministers to include a 35% affirmative action for women. 3. As at Thursday 29th September, 2016, the Gender and Equal Opportunities Bill, 2016, scaled through the Senate for second reading. -

16Th Acasa Triennial Symposium on African Art

AXIS G A L L E 16TH acasa R Bobson Sukhdeo Mohanlall Y TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART MARCH 19–22, 2014 ACASA ARTS COUNCIL OF THE AFRICAN STUDIES assOCIATION Hosted by Untitled. c. 1970.. On view at Skoto Gallery during ACASA 529 W 20th Street, 5th flr. New York March 11 - April 12, 2014 Tue. - Sat. 11–6 L O CA TION Floor 4 MORRIS A. AND MEYER SCHAPIRO WING Forum DONALD M. Period Rooms AND (all _.3 MARY P. sessions MA Donors to ACASA Funds OENSLAGER held GALLERY here) P ACASA gratefully acknowledges the following individuals for their generous S Staircase 4 Contemporary Art donations to our various funds since the last Triennial Symposium in 2011: Elevator B I ng Con ST RA ACASA Endowment Fund ep T ssi empo HA Decorative Decorative Eli Bentor 20th- A GALL A nie RAR Staircase 2 A William Dewey C nd entury E Y R Tim Rebecca Nagy A A Y RT RT rts O F Roy Sieber Dissertation Award Endowment Fund William Dewey Daniel Reed 19th-Century Decorative Wedgwood Robert T. Soppelsa Arts 19th-Century Decorative Arts and Wedgwood galleries are not yet Travel Endowment Fund wheelchair accessible. Pamela Allara Staircase 1 William Dewey Elevator A Kate Ezra Barbara Frank MORRIS A. AND MEYER SCHAPIRO WING Christine Mullen Kreamer Floor 5 Life, Death, and Transformation Rebecca Nagy BEATRICE AND in the Americas, SAMUEL A. SEAVER GALLERY IRIS AND Arts of the Americas Gallery B. GERALD CANTOR Triennial Fund GALLERY Ramona Austin HANNAH Staircase 4 LUCE CENTER FOR AMERICAN ART AND William Dewey American Identities LEONARD William Fagaly STONE Staircase 3 -

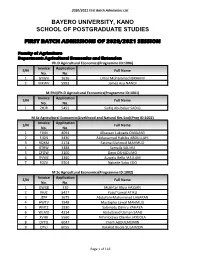

First Batch Admissions of 2020/2021 Session

2020/2021 First Batch Admissions List BAYERO UNIVERSITY, KANO SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES FIRST BATCH ADMISSIONS OF 2020/2021 SESSION Faculty of Agriculture Department: Agricultural Economics and Extension Ph.D Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1006) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 GYWH 1636 Umar Muhammad IBRAHIM 2 MXWV 5993 James Asu NANDI M.Phil/Ph.D Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1001) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 ZHJR 5491 Sadiq Abubakar SADIQ M.Sc Agricultural Economics(Livelihood and Natural Res Eco)(Prog ID:1002) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 FJVN 4091 Alhassan Lukpada DANLAMI 2 FJQN 3430 Abdussamad Habibu ABDULLAHI 3 RQXM 2174 Fatima Mahmud MAHMUD 4 BTRW 3488 Samaila SALIHU 5 CFQW 3100 Dayo OSHADUMO 6 RVWZ 3360 Auwalu Bello MALLAM 7 FDZV 5504 Ngbede Sabo EDO M.Sc Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1002) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 QWXB 330 Mukhtar Aliyu HASSAN 2 XHJC 5427 Yusuf Lawal ATIKU 3 JZFP 1675 Abdullahi Muhammad LABARAN 4 HWTV 1948 Mustapha Lawal MAHMUD 5 RMTZ 1930 Salamatu Dahiru YAHAYA 6 WLMD 4314 Abdulbasid Usman SAAD 7 XVHK 5560 Nihinlolawa Olanike JAYEOLA 8 DYTQ 6047 Imam ABDULMUMIN 9 CPVJ 6055 Barakat Bisola SULAIMON Page 1 of 116 2020/2021 First Batch Admissions List M.Sc Agricultural Extension(Programme ID:1003) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 DMWZ 36 Olayinka Adebola BELLO 2 PYHF 518 Isiagu Benedeth ANTHONY 3 RVFW 2291 Obako ENAHIBRAHIM 4 XFYN 2366 Kabiru MUSA 5 HBYD 5171 Musa GARBA Department: Agronomy Ph.D Agronomy(Programme ID:1108) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. -

Swindon Deanery Prayer Diary 2019 – Third Quarter

Swindon Deanery Prayer Diary 2019 – Third Quarter Date Swindon Deanery Cycle of Prayer Anglican Communion Cycle of Prayer Sunday Parish Please send amendments and corrections to [email protected] Sunday 7th July A village church, with a full range of services. Sunday 7 July 2019 Trinity 3 Prayer for the growing link with the Church school, local families to be Pray for the Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea Broad Blunsdon drawn to faith, and the opportunity of new housing for mission The Most Revd Allan Migi - Archbishop of Papua New Guinea Priest-in-Charge Revd Geoff Sowden Monday 8 July 2019 LLMs North West Australia (Australia) The Rt Revd Gary Nelson Mrs Kathryn Dack Awka (Nigeria)The Rt Revd Alexander Ibezim Kafanchan Mr. Paul Morris (Nigeria) The Rt Revd Marcus Dogo Churchwardens Mrs. Jane Ockwell Tuesday 9 July 2019 PCC Treasurer Northern Argentina (South America) The Rt Revd Nicholas Mrs. Lucy Sturgess James Quested Drayson PCC Secretary Northern Argentina (South America) The Rt Revd Mateo Mrs. Helen Griffiths Alto Northern Argentina (South America) The Rt Revd Crisanto GROWING DISCIPLES Rojas Exploring faith courses, run in conjunction with Highworth. Awori (Nigeria) The Rt Revd J Akin Atere GROWING LEADERS Mentoring of a coaching group by the Vicar Wednesday 10 July 2019 GROWING VOCATIONS Northern California (The Episcopal Church) The Rt Revd Mentoring of a coaching group by the Vicar Barry Beisner MISSION within the parish: Badagry (Nigeria) The Rt Revd Joseph Adeyemi Ballarat One nursing care home (Australia) The Rt Revd