'Conditions of Time and Space'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stern Twin-Propeller Effects on Harbor Infrastructures. Experimental Analysis

water Article Stern Twin-Propeller Effects on Harbor Infrastructures. Experimental Analysis Anna Mujal-Colilles 1,* , Marcel· la Castells 2, Toni Llull 1, Xavi Gironella 1 and Xavier Martínez de Osés 2 1 Marine Engineering Laboratory, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, C/ Jordi Girona 1, 08034 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (X.G.) 2 Department of Nautical Science and Engineering, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Pla de Palau, 18, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (M.l.C.), [email protected] (X.M.d.O.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-93-401-7017 Received: 12 October 2018; Accepted: 30 October 2018; Published: 2 November 2018 Abstract: The growth of marine traffic in harbors, and the subsequent increase in vessel and propulsion system sizes, produces three linked problems at the harbor basin area: (i) higher erosion rates damaging docking structures; (ii) sedimentation areas reducing the total depth; (iii) resuspension of contaminated materials deposited at the seabed. The published literature demonstrates that there are no formulations for twin stern propellers to compute the maximum scouring depth. Another important limitation is the fact that the formulations proposed only use one type of maneuvering during the experimental campaign, assuming that vessels are constantly being undocked. Trying to reproduce the real arrival and departure maneuvers, 24 different tests were conducted at an experimental laboratory in a medium-scale water tank using a twin propeller model to estimate the consequences and the maximum scouring depth produced by stern propellers during the backward/docking and forward/undocking scenarios. -

Is the Greek Crisis One of Supply Or Demand?

YANNIS M. IOANNIDES Tufts University CHRISTOPHER A. PISSARIDES London School of Economics Is the Greek Crisis One of Supply or Demand? ABSTRACT Greece’s “supply” problems have been present since its acces- sion to the European Union in 1981; the “demand” problems caused by austerity and wage cuts have compounded the structural problems. This paper discusses the severity of the demand contraction, examines product market reforms, many of which have not been implemented, and their potential impact on com- petitiveness and the economy, and labor market reforms, many of which have been implemented but due to their timing have contributed to the collapse of demand. The paper argues in favor of eurozone-wide policies that would help Greece recover and of linking reforms with debt relief. reece joined the European Union (EU) in 1981 largely on politi- Gcal grounds to protect democracy after the malfunctioning political regimes that followed the civil war in 1949 and the disastrous military dictatorship of the years 1967–74. Not much attention was paid to the economy and its ability to withstand competition from economically more advanced European nations. A similar blind eye was turned to the economy when the country applied for membership in the euro area in 1999, becom- ing a full member in 2001. It is now blatantly obvious that the country was not in a position to compete and prosper in the European Union’s single market or in the euro area. A myriad of restrictions on free trade had been introduced piecemeal after 1949, with the pretext of protecting those who fought for democracy. -

Doctor Who Sonic Screwdriver Universal Remote Control AVAILABLE in AUSTRALIA

BBC Worldwide Press Office BBC Worldwide Australia Level 5, 6 Eden Park Drive, Macquarie Park NSW 2113 …THE TIME LORD’S TECHNOLOGY FINALLY UNDER HUMAN CONTROL… Doctor Who Sonic Screwdriver Universal Remote Control AVAILABLE IN AUSTRALIA Thursday August 30, 2012 The Doctor Who Sonic Screwdriver Universal Remote Control - recently unveiled by The Wand Company and BBC Worldwide as the must-have accessory for Doctor Who fans - will be available for purchase from August 31 here in Australia prior to the return of Doctor Who on ABC1. Ever since Patrick Troughton, the Second Doctor, first produced it from his jacket, the sonic screwdriver has been the Doctor’s most trusted tool. Now, for the first time, Australian Doctor Who fans will have the opportunity to bring the Time Lord’s extremely cool and iconic gadget into their own homes. A high quality metal replica of the Mark VII Sonic Screwdriver currently used by the Eleventh Doctor, Matt Smith, the new Sonic Screwdriver Universal Remote Control is a gesture-based universal remote control that utilises infrared (IR) technology to manipulate almost all earth-based home entertainment systems - from TVs and iPod docks to DVD/Blu-ray players and beyond. With a green flashing tip and an impressive four operational modes – including a practice mode – and three memory banks, a total of 39 commands can be stored in the Sonic Screwdriver Universal Remote Control, giving aspiring Time Lord’s the option of operating multiple home entertainment devices with different flicks of the wrist. Control is straightforward – even for humans. The Sonic Screwdriver Universal Remote Control works through a series of 13 short gestures, such as rotating, flicking or tapping, and a guided set-up procedure uses spoken prompts to match gestures to commands learned from existing remote controls. -

A Producer's Handbook

DEVELOPMENT AND OTHER CHALLENGES A PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK by Kathy Avrich-Johnson Edited by Daphne Park Rehdner Summer 2002 Introduction and Disclaimer This handbook addresses business issues and considerations related to certain aspects of the production process, namely development and the acquisition of rights, producer relationships and low budget production. There is no neat title that encompasses these topics but what ties them together is that they are all areas that present particular challenges to emerging producers. In the course of researching this book, the issues that came up repeatedly are those that arise at the earlier stages of the production process or at the earlier stages of the producer’s career. If not properly addressed these will be certain to bite you in the end. There is more discussion of various considerations than in Canadian Production Finance: A Producer’s Handbook due to the nature of the topics. I have sought not to replicate any of the material covered in that book. What I have sought to provide is practical guidance through some tricky territory. There are often as many different agreements and approaches to many of the topics discussed as there are producers and no two productions are the same. The content of this handbook is designed for informational purposes only. It is by no means a comprehensive statement of available options, information, resources or alternatives related to Canadian development and production. The content does not purport to provide legal or accounting advice and must not be construed as doing so. The information contained in this handbook is not intended to substitute for informed, specific professional advice. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Doctor Who 4 Ep.18.GOLD.SCW

DOCTOR WHO 4.18 by Russell T Davies Shooting Script GOLDENROD ??th April 2009 Prep: 23rd February Shoot: 30th March Tale Writer's The Doctor Who 4 Episode 18 SHOOTING SCRIPT 20/03/09 page 1. 1 OMITTED 1 2 FX SHOT. GALLIFREY - DAY 2 FX: LONG FX SHOT, craning up to reveal the mountains of Gallifrey, as Ep.3.12 sc.40. But now transformed; the mountains are burning, a landscape of flame. The valley's a pit of fire, cradling the hulks of broken spaceships. Keep craning up to see, beyond; the Citadel of the Time Lords. The glass dome now cracked and open. CUT TO: 3 INT. CITADEL - DAY 3 FX: DMP WIDE SHOT, an ancient hallway, once beautiful, high vaults of stone & metal. But the roof is now broken, open to the dark orange sky, the edges burning. Bottom of frame, a walkway, along which walk THE NARRATOR, with staff, and 2 TIME LORDS, the latter pair in ceremonial collars. FX: NEW ANGLE, LONG SHOT, the WALKWAY curves round, Narrator & Time Lords now following the curve, heading towards TWO HUGE, CARVED DOORS, already open. A Black Void beyond. Tale CUT TO: 4 INT. BLACK VOID 4 FX: OTHER SIDE OF THE HUGE DOORS, NARRATOR & 2 TIME LORDS striding through. The Time Lords stay by the doors, on guard; lose them, and the doors, as the Narrator walks on. FX: WIDE SHOT of the Black Void - like Superman's Krypton, the courtroom/Phantom Zone scenes - deep black, starkly lit from above. Centre of the Void: a long table, with 5 TIME LORDS in robes Writer's(no collars) seated. -

Gardner • Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Edit No Proof

James Gardner Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Since his return to active service a few years ago1, Peter Zinovieff has appeared quite frequently in interviews in the mainstream press and online outlets2 talking not only about his recent sonic art projects but also about the work he did in the 1960s and 70s at his own pioneering computer electronic music studio in Putney. And no such interview would be complete without referring to EMS, the synthesiser company he co-founded in 1969, or namechecking the many rock celebrities who used its products, such as the VCS3 and Synthi AKS synthesisers. Before this Indian summer (he is now 82) there had been a gap of some 30 years in his compositional activity since the demise of his studio. I say ‘compositional’ activity, but in the 60s and 70s he saw himself as more animateur than composer and it is perhaps in that capacity that his unique contribution to British electronic music during those two decades is best understood. In this article I will discuss just some of the work that was done at Zinovieff’s studio during its relatively brief existence and consider two recent contributions to the documentation and contextualization of that work: Tom Hall’s chapter3 on Harrison Birtwistle’s electronic music collaborations with Zinovieff; and the double CD Electronic Calendar: The EMS Tapes,4 which presents a substantial sampling of the studio’s output between 1966 and 1979. Electronic Calendar, a handsome package to be sure, consists of two CDs and a lavishly-illustrated booklet with lengthy texts. -

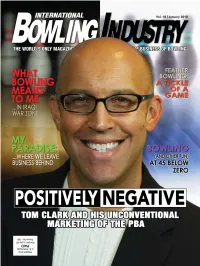

Freeze Frame by Lydia Rypcinski 8 Victoria Tahmizian Bowling and Other [email protected] Fun at 45 Below Zero

THE WORLD'S ONLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED EXCLUSIVELY TO THE BUSINESS OF BOWLING CONTENTS VOL 18.1 PUBLISHER & EDITOR Scott Frager [email protected] Skype: scottfrager 6 20 MANAGING EDITOR THE ISSUE AT HAND COVER STORY Fred Groh More than business Positively negative [email protected] Take a close look. You want out-of-the-box OFFICE MANAGER This is a brand new IBI. marketing? You want Tom Patty Heath By Scott Frager Clark. How his tactics at [email protected] PBA are changing the CONTRIBUTORS way the media, the public 8 Gregory Keer and the players look Lydia Rypcinski COMPASS POINTS at bowling. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Freeze frame By Lydia Rypcinski 8 Victoria Tahmizian Bowling and other [email protected] fun at 45 below zero. By Gregory Keer 28 ART DIRECTION & PRODUCTION THE LIGHTER SIDE Designworks www.dzynwrx.com A feather in your 13 (818) 735-9424 cap–er, lane PORTFOLIO Feather bowling’s the FOUNDER Allen Crown (1933-2002) What was your first game where the balls job, Cathy DeSocio? aren’t really balls, there are no bowling shoes, 13245 Riverside Dr., Suite 501 Sherman Oaks, CA 91423 and the lanes aren’t even 13 (818) 789-2695(BOWL) flat. But people come What was your first Fax (818) 789-2812 from miles around, pay $40 job, John LaSpina? [email protected] an hour, and book weeks in advance. www.BowlingIndustry.com 14 HOTLINE: 888-424-2695 What Bowling 32 Means to Me THE GRAPEVINE SUBSCRIPTION RATES: One copy of Two bowling International Bowling Industry is sent free to A tattoo league? every bowling center, independently owned buddies who built a lane 20 Go ahead and laugh but pro shop and collegiate bowling center in of their own when their the U.S., and every military bowling center it’s a nice chunk of and pro shop worldwide. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Nominations Announced for the Ee British Academy Film Awards in 2019

NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED FOR THE EE BRITISH ACADEMY FILM AWARDS IN 2019 London, 9 January 2019: The British Academy of Film and Television Arts has announced the nominations for the EE British Academy Film Awards in 2019. The Favourite is nominated in 12 categories. Bohemian Rhapsody, First Man, Roma and A Star Is Born each have seven nominations; Vice has six, BlacKkKlansman has five, and Cold War and Green Book have four each. Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Mary Poppins Returns, Mary Queen of Scots and Stan & Ollie have three nominations each. The Favourite is nominated for Best Film, Outstanding British Film, Original Screenplay, Cinematography, Production Design, Costume Design, Make Up & Hair, Editing and Yorgos Lanthimos for Director. Olivia Colman is nominated for Leading Actress for her role as Queen Anne, and Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone are both nominated for Supporting Actress. Roma is nominated for Best Film, Film Not in the English Language, Director, Original Screenplay, Cinematography, and Editing. Alfonso Cuarón is nominated in all of these categories. The film is also nominated for Production Design. A Star Is Born is nominated in seven categories; Leading Actor, Director, Adapted Screenplay, Original Music, Sound, Best Film and Leading Actress for Lady Gaga. Bradley Cooper is nominated for five of these categories. Bohemian Rhapsody receives nominations for Outstanding British Film, Cinematography, Editing, Sound, Costume Design, and Make Up & Hair, as well as Leading Actor for Rami Malek for his role as Freddie Mercury. First Man receives nominations for Adapted Screenplay, Cinematography, Editing, Production Design, Sound, and Special Visual Effects, as well as Supporting Actress for Claire Foy. -

Copyright Undertaking

Copyright Undertaking This thesis is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. By reading and using the thesis, the reader understands and agrees to the following terms: 1. The reader will abide by the rules and legal ordinances governing copyright regarding the use of the thesis. 2. The reader will use the thesis for the purpose of research or private study only and not for distribution or further reproduction or any other purpose. 3. The reader agrees to indemnify and hold the University harmless from and against any loss, damage, cost, liability or expenses arising from copyright infringement or unauthorized usage. IMPORTANT If you have reasons to believe that any materials in this thesis are deemed not suitable to be distributed in this form, or a copyright owner having difficulty with the material being included in our database, please contact [email protected] providing details. The Library will look into your claim and consider taking remedial action upon receipt of the written requests. Pao Yue-kong Library, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong http://www.lib.polyu.edu.hk WAR AND WILL: A MULTISEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF METAL GEAR SOLID 4 CARMAN NG Ph.D The Hong Kong Polytechnic University 2017 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Department of English War and Will: A Multisemiotic Analysis of Metal Gear Solid 4 Carman Ng A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2016 For Iris and Benjamin, my parents and mentors, who have taught me the courage to seek knowledge and truths among warring selves and thoughts. -

TORCHWOOD T I M E L I N E DRAMA I 2 K S 2 Sunday BBC3, Wednesday BBC2 ~*T0&> ' ""* Doctor Who Viewers Have Hear

DRAMA SundayI2KS BBC3,2 Wednesday BBC2 TORCHWOOD TIMELINE ~*t0&> ' ""* Doctor Who viewers have heard the name Torchwood before... 11 Jure 2005 In the series one episode It may be a Doctor Who spin-off, but Torchwood Sad Wolf, Torchwood is an is very much its own beast, says Russell T Davies answer on Weakest Link with Anne-droid (pictured above). % Jack's back. But he's changed - he's of course, their leader, and two of the other angrier. The last we saw of Captain actors have also appeared in Doctor Who: Eve 25 December 2005 Jack Harkness, at the tail end of the Myles, who played Victorian maid Gwyneth In The Christmas Invasion, Prime Minister Harriet Jones rejuvenated Doctor Who series one, he'd in The Unquiet Dead; and Naoko Mori continues reveals she knows about top- been exterminated by Daleks (see picture to play the role of Dr Toshiko Sato, last seen secret Torchwood - and orders below), been brought back to life and then examining a pig in a spacesuit in Aliens of London. it to destroy the Sycorax ship. abandoned by the Doctor to fend for himself. As you'll see from the cover and our profile on What does a flirtatious, sexy-beast Time Agent page 14, they're a glamorous bunch. Or, as 22 April 2006 from the 51 st century, understandably miffed at Myles puts it, "It's a very sexy world." In Tooth and Claw, set in being dumped, do next? Easy: he joins Torchwood. Their objective? Nothing less than keeping the Torchwood House, Queen Doctor Who fans - and there are a few - will world safe from alien threat.