Performing Shakespeare Extract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare Othello Mp3, Flac, Wma

Shakespeare Othello mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Non Music / Stage & Screen Album: Othello Country: US Style: Spoken Word MP3 version RAR size: 1178 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1926 mb WMA version RAR size: 1908 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 984 Other Formats: MP1 VOC MP2 WMA MP3 DMF AAC Tracklist A Othello B Othello Companies, etc. Recorded By – F.C.M. Productions Published By – Worlco Credits Composed By [Musique Concrete], Composed By [Sound Patterns] – Desmond Leslie Directed By – Michael Benthall Voice Actor [Brabantio] – Ernest Hare Voice Actor [Cassio] – John Humphry Voice Actor [Desdemona] – Barbara Jefford Voice Actor [Duke Of Venice] – Charles West Voice Actor [Emilia] – Coral Browne Voice Actor [Iago] – Ralph Richardson Voice Actor [Lodovico, Senator] – Joss Ackland Voice Actor [Narrator] – Michael Benthall Voice Actor [Othello] – John Gielgud Voice Actor [Sailor] – Stephen Moore Voice Actor [Senator] – David Tudor-Jones Voice Actor [Small Part] – David Lloyd-Meredith, Peter Ellis , Roger Grainger Written-By – William Shakespeare Notes Modern abridged version. An F.C.M. production. Includes a 16 page booklet. Australian WRC 2nd pressing, sourced from original stampers and featuring unique sleeve art. Same sleeve design as previous issue, except new addresses. The mono version has a red sticker with "mono" on the back (though these tend to drop off with age). "SLS-4" on labels, "LS/4" on sleeve. 299 Flinders Lane Melbourne 177 Elizabeth St Sydney Newspaper House, 93 Queen St Brisbane 60 Pulteney St Adelaide Barnett's Building, Council Ave Perth Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year William Othello (LP, Oldbourne Press, DEOB 3AS DEOB 3AS UK 1964 Shakespeare Album) Odhams Books Ltd. -

Actors and Accents in Shakespearean Performances in Brazil: an Incipient National Theater1

Scripta Uniandrade, v. 15, n. 3 (2017) Revista da Pós-Graduação em Letras – UNIANDRADE Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil ACTORS AND ACCENTS IN SHAKESPEAREAN PERFORMANCES IN BRAZIL: AN INCIPIENT NATIONAL THEATER1 DRA. LIANA DE CAMARGO LEÃO Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR) Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil ([email protected]) DRA. MAIL MARQUES DE AZEVEDO Centro Universitário Campos de Andrade, UNIANDRADE Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: The main objective of this work is to sketch a concise panorama of Shakespearean performances in Brazil and their influence on an incipient Brazilian theater. After a historical preamble about the initial prevailing French tradition, it concentrates on the role of João Caetano dos Santos as the hegemonic figure in mid nineteenth-century theatrical pursuits. Caetano’s memorable performances of Othello, his master role, are examined in the theatrical context of his time: parodied by Martins Pena and praised by Machado de Assis. References to European companies touring Brazil, and to the relevance of Paschoal Carlos Magno’s creation of the TEB for a theater with a truly Brazilian accent, lead to final succinct remarks about the twenty-first century scenery. Keywords: Shakespeare. Performances. Brazilian Theater. Artigo recebido em 13 out. 2017. Aceito em 11 nov. 2017. 1 This paper was first presented at the World Shakespeare Congress 2016 of the International Shakespeare Association, in Stratford-upon-Avon. LEÃO, Liana de Camargo; AZEVEDO, Mail Marques de. Actors and accents in Shakespearean performances in Brazil: An incipient national theater. Scripta Uniandrade, v. 15, n. 3 (2017), p. 32-43. Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil Data de edição: 11 dez. -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

Hamlet-Production-Guide.Pdf

ASOLO REP EDUCATION & OUTREACH PRODUCTION GUIDE 2016 Tour PRODUCTION GUIDE By WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ASOLO REP Adapted and Directed by JUSTIN LUCERO EDUCATION & OUTREACH TOURING SEPTEMBER 27 - NOVEMBER 22 ASOLO REP LEADERSHIP TABLE OF CONTENTS Producing Artistic Director WHAT TO EXPECT.......................................................................................1 MICHAEL DONALD EDWARDS WHO CAN YOU TRUST?..........................................................................2 Managing Director LINDA DIGABRIELE PEOPLE AND PLOT................................................................................3 FSU/Asolo Conservatory Director, ADAPTIONS OF SHAKESPEARE....................................................................5 Associate Director of Asolo Rep GREG LEAMING FROM THE DIRECTOR.................................................................................6 SHAPING THIS TEXT...................................................................................7 THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET CREATIVE TEAM FACT IN THE FICTION..................................................................................9 Director WHAT MAKES A GHOST?.........................................................................10 JUSTIN LUCERO UPCOMING OPPORTUNITIES......................................................................11 Costume Design BECKI STAFFORD Properties Design MARLÈNE WHITNEY WHAT TO EXPECT Sound Design MATTHEW PARKER You will see one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies shortened into a 45-minute Fight Choreography version -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

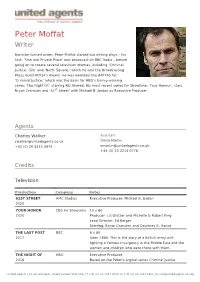

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

March 2016 Conversation

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE WNDC IN WASHINGTON THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION DIANA OWEN ♦ Tuesday, February 23 As we commemorate SHAKESPEARE 400, a global celebration of the poet’s life and legacy, the GUILD is delighted to co-host a WOMAN’S NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC CLUB gathering with DIANA OWEN, who heads the SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE TRUST in Stratford-upon-Avon. The TRUST presides over such treasures as Mary Arden’s House, WITTEMORE HOUSE Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, and the home in which the play- 1526 New Hampshire Avenue wright was born. It also preserves the site of New Place, the Washington mansion Shakespeare purchased in 1597, and in all prob- LUNCH 12:30. PROGRAM 1:00 ability the setting in which he died in 1616. A later owner Luncheon & Program, $30 demolished it, but the TRUST is now unearthing the struc- Program Only , $10 ture’s foundations and adding a new museum to the beautiful garden that has long delighted visitors. As she describes this exciting project, Ms. Owen will also talk about dozens of anniversary festivities, among them an April 23 BBC gala that will feature such stars as Dame Judi Dench and Sir Ian McKellen. PEGGY O’BRIEN ♦ Wednesday, February 24 Shifting to the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY, an American institution that is marking SHAKESPEARE 400 with a national tour of First Folios, we’re pleased to welcome PEGGY O’BRIEN, who established the Library’s globally acclaimed outreach initiatives to teachers and NATIONAL ARTS CLUB students in the 1980s and published a widely circulated 15 Gramercy Park South Shakespeare Set Free series with Simon and Schuster. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Talking Theatre Extract

Richard Eyre TALKING THEATRE Interviews with Theatre People Contents Introduction xiii Interviews John Gielgud 1 Peter Brook 16 Margaret ‘Percy’ Harris 29 Peter Hall 35 Ian McKellen 52 Judi Dench 57 Trevor Nunn 62 Vanessa Redgrave 67 NICK HERN BOOKS Fiona Shaw 71 London Liam Neeson 80 www.nickhernbooks.co.uk Stephen Rea 87 ix RICHARD EYRE CONTENTS Stephen Sondheim 94 Steven Berkoff 286 Arthur Laurents 102 Willem Dafoe 291 Arthur Miller 114 Deborah Warner 297 August Wilson 128 Simon McBurney 302 Jason Robards 134 Robert Lepage 306 Kim Hunter 139 Appendix Tony Kushner 144 John Johnston 313 Luise Rainer 154 Alan Bennett 161 Index 321 Harold Pinter 168 Tom Stoppard 178 David Hare 183 Jocelyn Herbert 192 William Gaskill 200 Arnold Wesker 211 Peter Gill 218 Christopher Hampton 225 Peter Shaffer 232 Frith Banbury 239 Alan Ayckbourn 248 John Bury 253 Victor Spinetti 259 John McGrath 266 Cameron Mackintosh 276 Patrick Marber 280 x xi JOHN GIELGUD Would you say the real father—or mother—of the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company is Lilian Baylis? Well, I think she didn’t know her arse from her elbow. She was an extraordinary old woman, really. And I never knew anybody who knew her really well. The books are quite good about her, but except for her eccentricities there’s nothing about her professional appreciation of Shakespeare. She had this faith which led her to the people she needed. Did she choose the actors? I don’t think so. She chose the directors. John Gielgud Yes, she had a very difficult time with them. -

INTRODUCTION Xl Othello a 'Black Devil' and Desdemona's 'Most Filthy

INTRODUCTION xl Othello a 'black devil' and Desdemona's 'most filthy bargain' ^ we cannot doubt that she speaks the mind of many an Englishwoman in the seventeenth-century audience. If anyone imagines that England at that date was unconscious of the 'colour-bar' they cannot have read Othello with any care? And only those who have not read the play at all could suppose that Shake speare shared the prejudice, inasmuch as Othello is his noblest soldier and he obviously exerted himself to represent him as a spirit of the rarest quality. How significant too is the entry he gives him! After listening for 180 lines of the opening scene to the obscene suggestions of Roderigo and lago and the cries of the outraged Brabantio we find ourselves in the presence of one, not only rich in honours won in the service of Venice, and fetching his 'life and being from men of royal siege',3 but personally a prince among men. Before such dignity, self-possession and serene sense of power, racial prejudice dwindles to a petty stupidity; and when Othello has told the lovely story of his courtshipj and Desdemona has in the Duke's Council- chamber, simply and without a moment's hesitation, preferred her black husband to her white father, we have to admit that the union of these two grand persons, * 5. 2.134, 160. The Devil, now for some reason become red, was black in the medieval and post-medievcil world. Thus 'Moors' had 'the complexion of a devil' {Merchant of Venice, i. 2. -

James Strong Director

James Strong Director Agents Michelle Archer Assistant Grace Baxter [email protected] 020 3214 0991 Credits Television Production Company Notes CRIME Buccaneer/Britbox Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2021 Episodes 1-3. Writer: Irvine Welsh, based on his novel by the same name. Producer: David Blair. Executive producers: Irvine Welsh, Dean Cavanagh, Dougray Scott andTony Wood. VIGIL World Productions / BBC One Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 - 2020 Episodes 1- 3. Starring Suranne Jones, Rose Leslie, Shaun Evans. Writer: Tom Edge. Executive Producer: Simon Heath. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes LIAR 2 Two Brothers/ ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Episodes 1-3. Writers: Jack and Harry Williams Producer: James Dean Executive Producer: Chris Aird Starring: Joanne Froggatt COUNCIL OF DADS NBC/ Jerry Bruckheimer Pilot Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Television/ Universal TV Inspired by the best-selling memoir of Bruce Feiler. Series ordered by NBC. Writers: Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. Producers: James Oh, Bruce Feiler. Exec Producers: Jerry Bruckheimer, Jonathan Littman, KristieAnne Read, Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. VANITY FAIR Mammoth/Amazon/ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2017 - 2018 Episodes 1,2,3,4,5&7 Starring Olivia Cooke, Simon Russell Beale, Martin Clunes, Frances de la Tour, Suranne Jones. Writer: Gwyneth Hughes. Producer: Julia Stannard. Exec Producers: Gwyneth Hughes, Damien Timmer, Tom Mullens. LIAR ITV/Two Brothers Pictures Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2016 - 2017 Episodes 1 to 3. Writers: Harry and Jack Williams. -

Introduction: Reflections on the Tragic in Contemporary American Drama and Theatre

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadt.commons.gc.cuny.edu Introduction: Reflections on the Tragic in Contemporary American Drama and Theatre by Johanna Hartmann and Julia Rössler The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 31, Number 2 (Winter 2019) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center In Tony Kushner’s provocative play Homebody/Kabul (2002), Milton reassures his daughter Priscilla during their trip to Afghanistan where they investigate the disappearance of Pricilla’s mother and Milton’s wife, “we shall respond to this tragedy by growing, growing close. .” Priscilla blankly replies, “people don’t grow close from tragedy. They wither is all, Dad, that’s all.”[1] While Milton interprets their situation as a tragic story from catastrophe to future hope, growth, and communality, Priscilla’s view is focused on the concrete suffering, defeat, and regress that will not contribute to some higher purpose. At the heart of this brief exchange between Milton and Priscilla lies a profound paradox which speaks of Kushner’s shrewd placement of tragedy between the human subjects’ transcendence and his or her irrevocable defeat. Similarly, in her play Desdemona: A Play About a Handkerchief (1994), Paula Vogel, deeply disturbed by the fact that when seeing Shakespeare’s Othello she would rather empathize with Othello than with Desdemona, poses the question if Desdemona deserved death, had she indeed been unfaithful to Othello. In Vogel’s rewrite of this classic tragedy, she reflects on how our individual response to what we see, our pity and empathy, depend on the formal and structural properties of a play but also on our sense of the social legitimacy for these feelings.[2] She shifts the focus from Othello to Desdemona and from Othello’s “flaw” of rogue jealousy to the systemic suppression of women in a patriarchal society.