ABSTRACT a Director's Approach to William Shakespeare's Hamlet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

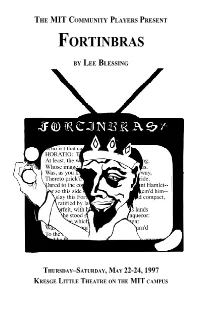

Fortinbras Program

THE MIT COMMUNITY PLAYERS PRESENT FORTINBRAS BY LEE BLESSING THURSDAY–SATURDAY, MAY 22-24, 1997 KRESGE LITTLE THEATRE ON THE MIT CAMPUS FORTINBRAS by Lee Blessing *Produced by special arrangement with Baker’s Plays The Persons of the Play Fortinbras ...................................... Steve Dubin Hamlet ........................................... Greg Tucker (S) Osric .............................................. Ian Dowell (A) Horatio........................................... Matt Norwood ’99 Ophelia .......................................... Erica Klempner (G) Claudius ........................................ Ben Dubrovsky (A) Gertrude ........................................ Anne Sechrest (affil) Laertes .......................................... Randy Weinstein (G) Polonius......................................... Peter Floyd (A, S) Polish Maiden 1............................. Alice Waugh (S) Polish Maiden 2............................. Anna Socrates Captain .......................................... Jim Carroll (A) English Ambassador ..................... Alice Waugh (S) Marcellus....................................... Eric Lindblad (G) Barnardo ....................................... Russell Miller ’00 The Scenes of the Play Act I: Elsinore — ten minute intermission — Act II: Still Elsinore (“S” indicates MIT staff member, “G” indicates graduate student, “A” indicates alumnus, and “affil” indicates affiliation with a member of the MIT community). Behind the Scenes Director............................................. Ronni -

View in Order to Answer Fortinbras’S Questions

SHAKESPEAREAN VARIATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF HAMLET, PRINCE OF DENMARK Steven Barrie A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor Dr. Kimberly Coates ii ABSTRACT Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor In this thesis, I examine six adaptations of the narrative known primarily through William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark to answer how so many versions of the same story can successfully exist at the same time. I use a homology proposed by Gary Bortolotti and Linda Hutcheon that explains there is a similar process behind cultural and biological adaptation. Drawing from the connection between literary adaptations and evolution developed by Bortolotti and Hutcheon, I argue there is also a connection between variation among literary adaptations of the same story and variation among species of the same organism. I determine that multiple adaptations of the same story can productively coexist during the same cultural moment if they vary enough to lessen the competition between them for an audience. iii For Pam. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Stephannie Gearhart, for being a patient listener when I came to her with hints of ideas for my thesis and, especially, for staying with me when I didn’t use half of them. Her guidance and advice have been absolutely essential to this project. I would also like to thank Kim Coates for her helpful feedback. She has made me much more aware of the clarity of my sentences than I ever thought possible. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’S Hamlet

The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mosley, Joseph Scott. 2017. The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33826315 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Dilemma of Shakespearean Sonship: An Analysis of Paternal Models of Authority and Filial Duty in Shakespeare’s Hamlet Joseph Scott Mosley A Thesis in the Field of Dramatic Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2017 © 2017 Joseph Scott Mosley Abstract The aim of the proposed thesis will be to examine the complex and compelling relationship between fathers and sons in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This study will investigate the difficult and challenging process of forming one’s own identity with its social and psychological conflicts. It will also examine how the transformation of the son challenges the traditional family model in concert or in discord with the predominant philosophy of the time. I will assess three father-son relationships in the play – King Hamlet and Hamlet, Polonius and Laertes, and Old Fortinbras and Fortinbras – which thematize and explore filial ambivalence and paternal authority through the act of revenge and mourning the death of fathers. -

Hamlet-Production-Guide.Pdf

ASOLO REP EDUCATION & OUTREACH PRODUCTION GUIDE 2016 Tour PRODUCTION GUIDE By WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ASOLO REP Adapted and Directed by JUSTIN LUCERO EDUCATION & OUTREACH TOURING SEPTEMBER 27 - NOVEMBER 22 ASOLO REP LEADERSHIP TABLE OF CONTENTS Producing Artistic Director WHAT TO EXPECT.......................................................................................1 MICHAEL DONALD EDWARDS WHO CAN YOU TRUST?..........................................................................2 Managing Director LINDA DIGABRIELE PEOPLE AND PLOT................................................................................3 FSU/Asolo Conservatory Director, ADAPTIONS OF SHAKESPEARE....................................................................5 Associate Director of Asolo Rep GREG LEAMING FROM THE DIRECTOR.................................................................................6 SHAPING THIS TEXT...................................................................................7 THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET CREATIVE TEAM FACT IN THE FICTION..................................................................................9 Director WHAT MAKES A GHOST?.........................................................................10 JUSTIN LUCERO UPCOMING OPPORTUNITIES......................................................................11 Costume Design BECKI STAFFORD Properties Design MARLÈNE WHITNEY WHAT TO EXPECT Sound Design MATTHEW PARKER You will see one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies shortened into a 45-minute Fight Choreography version -

Edward II: Negotiations of Credit in the Early Modern Public Sphere Jane E

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2018 Edward II: Negotiations of Credit in the Early Modern Public Sphere Jane E. Kuebler Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Kuebler, Jane E., "Edward II: Negotiations of Credit in the Early Modern Public Sphere" (2018). All Theses. 2856. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2856 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edward II: Negotiations of Credit in the Early Modern Public Sphere A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts English by Jane E. Kuebler May 2018 Accepted by: Dr. Elizabeth Rivlin, Committee Chair Dr. William Stockton Dr. Andrew Lemons ABSTRACT This paper addresses the role that Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II plays in the establishing and expanding of an early modern public sphere. By examining the ways that power is earned, and wielded in the play, Marlowe demonstrates an economy of cultural credit that operates in both the financial and the socio/political spheres of public life in early modern England. Marlowe applies the logic of that economy beyond the realm of the common people and subjects the historical monarch to the same parameters of judgement that flourished in society, drawing parallels with the currently reigning Elizabeth I, and opening up a discourse that reexamines the markers of credit, power and birth-ordered hierarchies. -

Timberlake Wertenbaker - Cv

TIMBERLAKE WERTENBAKER - CV Timberlake Wertenbaker is working on new commissions for the Royal Shakespeare Company, Bolton Octagon and Salisbury Playhouse. OUR COUNTRY'S GOOD will be produced at the National Theatre in 2015, directed by Nadia Fall. THEATRE: JEFFERSON'S GARDEN 2015 Watford Palace Theare, world premiere Dir: Brigid Larmour THE ANT AND THE CICADA (RSC) 2014 Midsummer Madness Dir: Erica Whyman OUR AJAX (Southwark Playhouse / Natural Perspective) 2013 Dir: David Mercatali Original play, inspired by the Sophocles play OUR COUNTRY'S GOOD (Out Of Joint) Dir: Max Stafford-Clark UK Tour & St James Theatre, London - 2013 US Tour - 2014 ANTIGONE (The Southwark Playhouse) 2011 Dir: Tom Littler THE LINE (The Arcola Theatre) 2009 Dir: Matthew Lloyd JENUFA (The Arcola Theatre) 2007 Dir: Irena Brown GALILEO'S DAUGHTER (Theatre Royal, Bath) 2004 Dir: Sir Peter Hall CREDIBLE WITNESS (Royal Court Theatre) 2001 Dir: Sacha Wares ASH GIRL (Birmingham Rep) 2000 Dir: Lucy Bailey (Adaptation of Cinderella) AFTER DARWIN (Hampstead Theatre) 1998 Dir: Lindsay Posner THE BREAK OF THE DAY (Royal Court/Out of Joint tour) 1995 Dir: Max Stafford-Clark OUR COUNTRY'S GOOD (Broadway) 1990 Dir: Mark Lamos Winner: New York Drama Critics Award for best foriegn play THREE BIRDS ALIGHTING ON A FIELD (Royal CourtTheatre) 1991 Dir: Max Stafford-Clarke Winner: Writers Guild Award Winner: Susan Smith Blackburn prize THE LOVE OF THE NIGHTINGALE (RSC) 1988 Dir: Garry Hines OUR COUNTRY'S GOOD (Royal Court Theatre) 1985 Dir: Max Stafford-Clarke Winner: Olivier Award Play -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

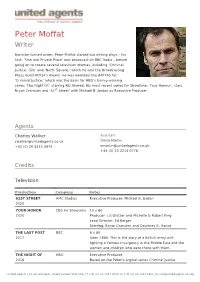

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

The Case of Hal and Henry IV in 1 & 2 Henry IV and the Famovs Victories

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book Jepson School of Leadership Studies chapters and other publications 2016 The iF lial Dagger: The aC se of Hal and Henry IV in 1 & 2 Henry IV and The Famovs Victories Kristin M.S. Bezio University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/jepson-faculty-publications Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bezio, Kristin. “The iF lial Dagger: The asC e of Hal and Henry IV in 1 & 2 Henry IV and The Famovs Victories,” Journal of the Wooden O 14-15 (2016): 67-83. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jepson School of Leadership Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book chapters and other publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 67 The Filial Dagger: The Case of Hal and Henry IV in 1 & 2 Henry IV and The Famovs Victories Kristin M. S. Bezio University of Richmond nglish culture and politics in the last decade of the sixteenth century were both patriarchal and patrilineal, in spite of— E or, perhaps, in part, because of—the so-called bastard queen sitting on the throne. The prevailing political questions of the day concerned Elizabeth’s successor and the fate of the nation that, so many believed, hung precariously in the balance.