Battle of New Orleans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Drafting Template

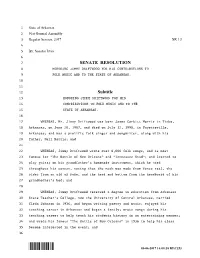

1 State of Arkansas 2 91st General Assembly 3 Regular Session, 2017 SR 13 4 5 By: Senator Irvin 6 7 SENATE RESOLUTION 8 HONORING JIMMY DRIFTWOOD FOR HIS CONTRIBUTIONS TO 9 FOLK MUSIC AND TO THE STATE OF ARKANSAS. 10 11 12 Subtitle 13 HONORING JIMMY DRIFTWOOD FOR HIS 14 CONTRIBUTIONS TO FOLK MUSIC AND TO THE 15 STATE OF ARKANSAS. 16 17 WHEREAS, Mr. Jimmy Driftwood was born James Corbitt Morris in Timbo, 18 Arkansas, on June 20, 1907, and died on July 12, 1998, in Fayetteville, 19 Arkansas; and was a prolific folk singer and songwriter, along with his 20 father, Neil Morris; and 21 22 WHEREAS, Jimmy Driftwood wrote over 6,000 folk songs, and is most 23 famous for “The Battle of New Orleans” and “Tennessee Stud“; and learned to 24 play guitar on his grandfather’s homemade instrument, which he used 25 throughout his career, noting that the neck was made from fence rail, the 26 sides from an old ox yoke, and the head and bottom from the headboard of his 27 grandmother’s bed; and 28 29 WHEREAS, Jimmy Driftwood received a degree in education from Arkansas 30 State Teacher’s College, now the University of Central Arkansas, married 31 Cleda Johnson in 1936, and began writing poetry and music; enjoyed his 32 teaching career in Arkansas and began a family; wrote songs during his 33 teaching career to help teach his students history in an entertaining manner; 34 and wrote his famous “The Battle of New Orleans” in 1936 to help his class 35 become interested in the event; and 36 *KLC253* 03-06-2017 14:08:28 KLC253 SR13 1 WHEREAS, it was not until the -

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected]

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS NOVEMBER 25, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 20 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Lady A’s Country Artists As Emotionally Torn Ocean Sails >page 4 By Impeachment As Their Fan Base “Old Town” Rode November Lee Greenwood might need to rewrite “God Bless the U.S.A.” in the current climate, and it’s particularly discouraging that Awards Nearly three years into a divisive presidency, the 53rd annual they have a difficult time even settling on reality. >page 10 Country Music Association Awards coincided with the start of “It’s he said/she said,” said LOCASH’s Chris Lucas. “I don’t impeachment hearings on Nov. 13. Judging from the reaction know who to believe or what to believe. There’s two sides, and of the genre’s artists, the opening line in Greenwood’s chorus — the two sides have figured out how to work [the media].” “I’m proud to be an Cash’s father, The Word From American” — is still Johnny Cash, was Garth Brooks a prominent belief. an outspoken sup- >page 11 But “I’m frustrated porter of inclusive to be an American” values, challeng- is hard on its heels as ing the ruling class Still In The Swing: a replacement. in his 1970 single An unscientific “What Is Truth.” Asleep At 50 LOCASH RAY CASH red-carpet poll of Just two years later, >page 11 the creative com- Rosanne cam- munity about the hearings found a wide range of awareness, paigned as a teenager for Democrat George McGovern in his from Rosanne Cash, who said she was “passionate” about bid to unseat Richard Nixon in the White House, and she has Makin’ Tracks: watching them, to a slew of artists who barely knew they were consistently stood up for progressive policies and politicians Tenpenny, Seaforth happening. -

“The Stories Behind the Songs”

“The Stories Behind The Songs” John Henderson The Stories Behind The Songs A compilation of “inside stories” behind classic country hits and the artists associated with them John Debbie & John By John Henderson (Arrangement by Debbie Henderson) A fascinating and entertaining look at the life and recording efforts of some of country music’s most talented singers and songwriters 1 Author’s Note My background in country music started before I even reached grade school. I was four years old when my uncle, Jack Henderson, the program director of 50,000 watt KCUL-AM in Fort Worth/Dallas, came to visit my family in 1959. He brought me around one hundred and fifty 45 RPM records from his station (duplicate copies that they no longer needed) and a small record player that played only 45s (not albums). I played those records day and night, completely wore them out. From that point, I wanted to be a disc jockey. But instead of going for the usual “comedic” approach most DJs took, I tried to be more informative by dropping in tidbits of a song’s background, something that always fascinated me. Originally with my “Classic Country Music Stories” site on Facebook (which is still going strong), and now with this book, I can tell the whole story, something that time restraints on radio wouldn’t allow. I began deejaying as a career at the age of sixteen in 1971, most notably at Nashville’s WENO-AM and WKDA- AM, Lakeland, Florida’s WPCV-FM (past winner of the “Radio Station of the Year” award from the Country Music Association), and Springfield, Missouri’s KTTS AM & FM and KWTO-AM, but with syndication and automation which overwhelmed radio some twenty-five years ago, my final DJ position ended in 1992. -

WDAM Radio Presents the Rest of the Story

WDAM Radio Presents The Rest Of The Story # Artist Title Chart Comments Position/Year 0000 Mr. Announcer & The “Introduction/Station WDAM Radio Singers Identification” 0001 Big Mama Thornton “Hound Dog” #1-R&B/1953 0001A Rufus Thomas "Bear Cat" #3-R&B/1953 0001A_ Charlie Gore & Louis “You Ain't Nothin' But A –/1953 Innes Female Hound Dog” 0001AA Romancers “House Cat” –/1955 0001B Elvis Presley “Hound Dog” #1/1956 0001BA Frank (Dual Trumpet) “New Hound Dog” –/1956 Motley & His Crew 0001C Homer & Jethro “Houn’ Dog (Take 2)” –/1956 0001D Pati Palin “Alley Cat” –/1956 0001E Cliff Johnson “Go ‘Way Hound Dog” –/1958 0002 Gary Lewis & The "Count Me In" #2/1965 Playboys 0002A Little Jonna Jaye "I'll Count You In" –/1965 0003 Joanie Sommers "One Boy" #54/1960 0003A Ritchie Dean "One Girl" –/1960 0004 Angels "My Boyfriend's Back" #1/1963 0004A Bobby Comstock & "Your Boyfriend's Back" #98/1963 The Counts 0004AA Denny Rendell “I’m Back Baby” –/1963 0004B Angels "The Guy With The Black Eye" –/1963 0004C Alice Donut "My Boyfriend's Back" –/1990 adult content 0005 Beatles [with Tony "My Bonnie" #26/1964 Sheridan] 0005A Bonnie Brooks "Bring Back My Beatles (To –/1964 Me)" 0006 Beach Boys "California Girls" #3/1965 0006A Cagle & Klender "Ocean City Girls" –/1985 0006B Thomas & Turpin "Marietta Girls" –/1985 0007 Mike Douglas "The Men In My Little Girl's #8/1965 Life" 0007A Fran Allison "The Girls In My Little Boy's –/1965 Life" 0007B Cousin Fescue "The Hoods In My Little Girl's –/1965 Life" 0008 Dawn "Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round #1/1973 the Ole Oak Tree" -

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events. -

Mundealan2011-12-08Transcript.Pdf (1.076Mb)

Oral History Interview of Alan Munde Interviewed by: Andy Wilkinson December 8, 2011 Wimberley, Texas Part of the: Crossroads of Music Archive Texas Tech University’s Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Oral History Program Copyright and Usage Information: An oral history release form was signed by Alan Munde on December 8, 2011. This transfers all rights of this interview to the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University. This oral history transcript is protected by U.S. copyright law. By viewing this document, the researcher agrees to abide by the fair use standards of U.S. Copyright Law (1976) and its amendments. This interview may be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes only. Any reproduction or transmission of this protected item beyond fair use requires the written and explicit permission of the Southwest Collection. Please contact Southwest Collection Reference staff for further information. Preferred Citation for this Document: Munde, Alan Oral History Interview, December 8, 2011. Interview by Andy Wilkinson, Online Transcription, Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library. URL of PDF, date accessed. The Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library houses almost 6000 oral history interviews dating back to the late 1940s. The historians who conduct these interviews seek to uncover the personal narratives of individuals living on the South Plains and beyond. These interviews should be considered a primary source document that does not implicate the final verified narrative of any event. These are recollections dependent upon an individual’s memory and experiences. The views expressed in these interviews are those only of the people speaking and do not reflect the views of the Southwest Collection or Texas Tech University. -

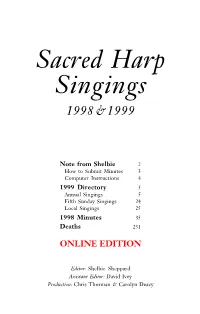

Sacred Harp Minutes 1998

Sacred Harp Singings 1998 & 1999 Note from Shelbie 2 How to Submit Minutes 3 Computer Instructions 4 1999 Directory 5 Annual Singings 5 Fifth Sunday Singings 24 Local Singings 25 1998 Minutes 35 Deaths 231 ONLINE EDITION Editor: Shelbie Sheppard Assistant Editor: David Ivey Production: Chris Thorman & Carolyn Deacy January 1, 1999 Dear Singers and Friends of Sacred Harp, I want to take this opportunity to thank all of you who took the time to help me in any way with this edition of the minutes book. Address changes from rural routes to street numbers or county road numbers were made, along with area code changes. A great many of these corrections were made, but I am sure there are others. If your address changed and we didn’t get it corrected, please send it to me. Also, many singings have changed the dates of their singings or combined them with other singings, so check the listings in the directory of singings section. It has been a year of a lot of changes! A problem has arisen that needs to be addressed. In the fabulous world of technology there still remain some problems connected with these new advances. One such problem is the fact that when you send minutes via e-mail, you do not send a check with it. It is extremely difficult to keep up with who has and has not mailed a check. If you are among this group, please note that I will not include your singing minutes in the book until I have received a hard copy with a check enclosed. -

Folk Artist # of Albumstitles Andersen

Folk Artist # of AlbumsTitles Andersen, Eric 4 bout Changes & Things; The Best of Eric Andersen; More Hits from Tin Can Alley; Blue River Axton, Hoyt 2 Joy To The World; Southbound Baez, Joan 10 Diamonds & Rust; Farewell Angelina;Come From The Shadows;The First 10 Years; Joan; One Day At A Time; Blessed are…; Any Day Now; Joan Baez 5; The Joan Baez Ballad Book Batdorf & Rodney 1 Life Is You Bawdy Songs & Backroom Ballads 7 Bawdy Sea Shanties; Bawdy Songs & Backroom Ballads Vol 1; Vol 3; Vol 4; Vol 6; Sing Along; Bawdy Hootenanny Belafonte, Harry 3 An Evening with Belafonte; Harry Belafonte Pure Gold; Belafonte Bikel, Theo 2 A Folksingers Choice; A New Day Blues Project 1 The Blues Project Live At Town Hall Bonoff, Karla 2 Karla Bonoff; Restless Nights Bowers, Bryan 1 The View From Home Bread & Roses 1 Bread & Roses Bromberg, David 2 Demon in Disguise; The Best Of David Bromberg Browne, Jackson 5 The Pretender; Running On Empty; Late For The Sky; For Everyman; Saturate Before Using Camp, Hamilton 2 Paths of Victory; Welcome to Hamilton Camp Cashman & West 1 A Song or Two Clancy Brothers 3 Green In The Green; In Person At Carnegie Hall; Sing of the Sea Collins, Judy 12 Living; Judy Collins; Judith; Judy Collins 3;True Stories; Who Knows Where The Time Goes; Wildflowers; In My Life; Fifth Album; The Judy Collins Concert; A Maid of Constant Sorrow; Golden Apples of the Sun Cooney, Michael 3 Singer of Old Songs; Still Cooney After All These Years; The Cheese Stands Alone Donovan 4 The Best Of Donovan; Donovan in Concert; Thye Real Donovan; -

Country Shows at the Flame Jimmy Wells

Country Shows at the Flame Jimmy Wells; Ardis Wells; Princess Jo Ann February 23 1956 Tex Ritter; TBS; Jimmy Wells May 16 1956 Tabby West; TBS; Jimmy Wells May 23 1956 Betty Foley; The Westerners - World's only Square Dance Roller Skaters; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup May 30 - June 2 1956 Marvin Rainwater; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup June 6 - 9 1956 Bobby Lord and Wanda Jackson; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup June 13 - 16 1956 Billy Walker; The Westerners; TBS; Jimmy Wells June 20 - 23 1956 Mac Weisman; TBS; Jimmy Wells June 27 - 30 1956 Justin Tubb; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup July 4 - 7 1956 Arlie Duff; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup July 11 - 14 1956 Jerry Reed; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup July 18 - 21 1956 Joe Carson (Wells on vacation) July 25 - 28 1956 Marvin Rainwater; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup August 1 - 4 1956 Lee Emerson, Everly Brothers; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup August 8 - 9 1956 Marvin Rainwater; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup August 10 - 11 1956 Bobby Lord; TBS; Jimmy Wells August 15 - 18 1956 Del Woods; Bonnie Sloan August 23 1956 Autrey Inman; TBS; Jimmy Wells August 22 - 25 1956 Mitchell Torok; TBS; Jimmy Wells Dakota Roundup August 29 - September 1 1956 Mrs. Hank Williams (Miss Audrey); TBS; Jimmy Wells September 5 - 8 1956 Jimmy Roberts; TBS; Jimmy Wells September 12 - 15 1956 Leon Payne; TBS; Jimmy Wells September 19 - 22 1956 Cowboy Copas; TBS; Jimmy Wells September 26 - 29 1956 Marvin Rainwater and Mimi Roman September 27 1956 Justin Tubb; TBS; Jimmy Wells October 10 - 13 1956 Mimi Roman; -

Tennessee Stud

TeBy Jimmy n Driftwood, n e © s 1958 s Warden e e Music S Company, t u Inc. d (BMI) D Along about eighteen and twenty-five; CHORUS C I left Tennessee very much alive. Drifted on down into no man's land; D Crossed the river called the Rio Grande. I never would have got through the Arkansas mud, I raced my hoss with the Spaniards foal; C D Till I got me a skin full of silver and gold. If I hadn't been a-ridin on the Tennessee stud. Me and a gambler, we couldn't agree; Got in a fight over Tennessee. D We jerked our guns, he fell with a thud, I had some trouble with my sweetheart's pa. And I got away on the Tennessee stud. C One of her brothers was a bad outlaw. CHORUS D I sent her a letter by my Uncle Fudd; Got as lonesome as a man can be, C D Dreamin' of my girl in Tennessee. And I rode away on the Tennessee stud The Tennessee stud's green eyes turned blue; 'Cause he was a-dreamin' of a sweetheart too. CHORUS D C D We loped on back across Arkansas; The Tennessee stud was long and lean; I whipped her brother and I whipped her pa. G F A I found that girl with the golden hair, The color of the sun and his eyes were green. She was ridin' on a Tennessee mare. D C D He had the nerve and he had the blood; CHORUS C D And there never was a hoss like the Tennessee stud. -

Diana Davies Photographs, 1963-2009

Diana Davies photographs, 1963-2009 Stephanie Smith, Joyce Capper, Jillian Foley, and Meaghan McCarthy 2004-2005 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 General note.................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Newport Folk Festival, 1964-1992, undated............................................. 6 Series 2: Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1967 - 1987.................................................. 46 Series 3: Broadside -

“The Stories Behind the Songs”

“The Stories Behind The Songs” John Henderson The Stories Behind The Songs A compilation of “inside stories” behind classic country hits and the artists associated with them John Debbie & John By John Henderson (Arrangement by Debbie Henderson) A fascinating and entertaining look at the life and recording efforts of some of country music’s most talented singers and songwriters 1 Author’s Note My background in country music started before I even reached grade school. I was four years old when my uncle, Jack Henderson, the program director of 50,000 watt KCUL-AM in Fort Worth/Dallas, came to visit my family in 1959. He brought me around one hundred and fifty 45 RPM records from his station (duplicate copies that they no longer needed) and a small record player that played only 45s (not albums). I played those records day and night, completely wore them out. From that point, I wanted to be a disc jockey. But instead of going for the usual “comedic” approach most DJs took, I tried to be more informative by dropping in tidbits of a song’s background, something that always fascinated me. Originally with my “Classic Country Music Stories” site on Facebook (which is still going strong), and now with this book, I can tell the whole story, something that time restraints on radio wouldn’t allow. I began deejaying as a career at the age of sixteen in 1971, most notably at Nashville’s WENO-AM and WKDA- AM, Lakeland, Florida’s WPCV-FM (past winner of the “Radio Station of the Year” award from the Country Music Association), and Springfield, Missouri’s KTTS AM & FM and KWTO-AM, but with syndication and automation which overwhelmed radio some twenty-five years ago, my final DJ position ended in 1992.