Cherokee Landing State Park Resource Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARPET CLEANING SPECIAL K N O W ? Throughout History, I Dogs Have Been the on OU> 211 Most Obvious Agents in 5 MILES SO

remain young and beautiful only by bathing in and in the story of Lauren Elder’s grueling 36-hour or S a t u r d a y drinking the blood of young innocent girls — includ deal following the crash of a light aiplane that killed ing her daughter’s. 12:30 a.m. on WQAD. her two companions. The two-hour drama is based "Tarzan’s New Adventure” —- Bruce Bennett and "Sweet, Sweet Rachel” — An ESP expert is pit on the book by Lauren Elder and Shirley Ula Holt star in the 1936 release. 1 p.m. on WMT. ted against an unseen presence that is trying to drive Streshinsky. 8 p.m. on NBC. "Harlow” — The sultry screen star of the 1930s is a beautiful woman crazy. The 1971 TV movie stars "Walk, Don’t Run” — A young woman (Saman the subject of the 1965 film biography with- Carroll Alex Dreier, Stefanie Powers, Pat Hingle and Steve tha Eggar) unwittingly agrees to share her apart Baker, Peter Lawford, Red Buttons, Michael Con Ihnat. 12:30 a.m. on KCRG. ment with a businessman (Cary Grant) and an athe- nors and Raf Vallone 1 p.m. on WOC lete (Jim Hutton) during the Tokyo Olympics (1966). "The Left-Handed Gun” — Paul Newman, Lita 11 p.m. on WMT Milan and Hurd Hatfield are the stars of the 1958 S u n d a y western detailing Billy the Kid’s career 1 p.m. on "The Flying Deuces” — Stan Laurel and Oliver KWWL. Hardy join the Foreign Legion so Ollie can forget an T u e s d a y "The Swimmer” — John Cheever’s story about unhappy romance (1939). -

Michael Preece

Deutscher FALCON CREST - Fanclub July 31, 2009 The First Director: MICHAEL PREECE Talks about the Falcon Crest Première and Other Memories Interview by THOMAS J. PUCHER (German FALCON CREST Fan Club) I sent Michael Preece, who directed ten episodes of Falcon Crest, particularly the series première, a request for an interview via e-mail, and he replied immediately so we scheduled a phone conversation for July 31, 2009. He has been one of the most successful directors of U.S. TV shows for more than 30 years. His directing credits include many hit series from the 1970’s, ’80’s and ’90’s, such as The Streets of San Francisco, Knots Landing, Fantasy Island, Flamingo Road, Trapper John, M.D., The Incredible Hulk, T.J. Hooker, Riptide, Stingray, Jake and the Fatman, MacGyver, Hunter, Renegade, Seventh Heaven and Walker, Texas Ranger as well as — last but not least — Dallas. Getting to Work on Falcon Crest Michael stepped right into the middle of how much he enjoyed working on Falcon Crest, particularly with Jane Wyman. He said she wanted him to direct more often, but he was extremely busy with Dallas: “I had to go to Jane Wyman and tell her that I couldn’t work on the show.” He left no doubt that directing Dallas did not leave much room for anything else because he directed approximately 70 episodes of the series. But he enjoyed doing an episode of Falcon Crest from time to time. “So how did you get your first assignment for Falcon Crest, the first episode, In His Father’s House?” I asked. -

Reversible BRAIDED RUGS BROWN TONES ONLY

Page A-8 TORRANCE PRESS Sunday, August 21, I960 (Jeorge Ori/xard. stars as a junior executive who com mits blunders that project him into a tragedy, in "The Twisted Image." premiere drama on the NBC-TV Net work's full-hour Tuesday night "Thriller" series Sept. 13. Boris Karloff is host of the series. Huhbell Robinson CARTWRIGHTS CORRALLED The stars of which portrays the members of the Cart- is executive producer. Co- NBC-produced "Bonanza" color film series wright family three half-brothers and their starred with (ifi/^ard on the are a frolicky foursome as they get set for father are (left to right) Lome Green as "Thriller" premiere are Na their second season of adventures on the Ben, the father, Dan Boclcer as Hoss, Michael talie 'IVundy. Leslie Nielsen full-hour colorcasts which start on the NBC- Lanjion as Little Joe and Pernell Roberts as Koster. and Diane UNITED STATES STEEL HOUR A hasty ceremony and a bor TV network Saturday, Sept. 10. The group Adam. + * * * rowed wedding ring unite Richard Kiley, as a Confederate $ol-| .lan Murray returns to the dier-spy, and Ina Balin, in marriage, just before Union troops NBC-TV NetwA-k Sept, "> as discover their whereabouts, during rehearsals for "Bride of the star and host, dfipis own Mon- Fox." The "live" U. S. Steel Hour drama, based on a true Civil 'day-through-KTepay afternoon War incident, will be seen on Wednesday, Aug. 24, at 10 p.m., colorcast series. On the new via Channel 2. ".lan Murray Show" the comedian will chat with con testants before they play a f a s t. -

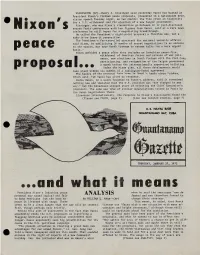

And What It Means

WASHINGTON ( AP)--Henry A. Kissinger said yesterday Hanoi has balked at President Nixo n's Vietnam peace proposals, presented in a nationwide ele- vision speech Tuesday night, on two counts: the fine print on blueprints for a U.S. wit idrawal and the election of a new Saigon government. Kissinger, w ho was Nixon's clandestine go-between in 12 just-disclosed H IXOH S secret Paris c conferences with key figures from Hanoi, said at a rare news conference he still hopes for a negotiating breakthrough. He called th e Presidents eight-point proposal a flexible one, not a take-it-or-leal ve-it proposition. The Presiden t's far-travelled assistant for national security affairs said Nixon, by publicizing 26 months of secret negotiations in an address peaceto the nation, may spur North Vietnam to resume talks "on a more urgent basis.", Nixon unfold ed a peace offer that includes an Indochina cease-fire, withdrawal of American forces and release of war pris- oners, new elections in South Vietnam with the Viet Cong participating, and resignation of the Saigon government a month before the internationally supervised balloting. proposal. Under the Nixon plan, all these developments would take place within six months of a Washington-Hanoi agreement. The basics of the proposal have ie an in 7hanni's hands since Octoberr, Nixon said, bu t Hanoi has given no response. Radio Hanoi, in a quick response to Nixon's address, said it contained nothing new an d insisted that the U.S. position was "not changed in any way." But the broadcast stopped short of rejecting the Chief Executive's proposals. -

The Zombie in American Culture by Graeme Stewart a Thesis Presented

The Zombie in American Culture by Graeme Stewart A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English - Literary Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Graeme Stewart 2013 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT My research explores how the oft-maligned zombie genre reveals deep-seated American cultural tendencies drawn from the nation's history with colonization and imperialism. The zombie genre is a quintessentially American construct that has been flourishing in popular culture for nearly 60 years. Since George A. Romero first pioneered the genre with 1968's Night of the Living Dead , zombie narratives have demonstrated a persistent resilience in American culture to emerge as the ultimate American horror icon. First serving as a method to exploit and react to cultural anxieties in the 1960s, the zombie genre met the decade's tumultuous violence in international conflicts like the Vietnam War and domestic revolutions like the Civil Rights Movement. It adapted in the 1970s to expose a perceived excess in consumer culture before reflecting apocalyptic fears at the height of the Cold War in the 1980s. Following a period of rest in the relatively peaceful 1990s, the genre re-emerged in the early 2000s to reflect cultural anxieties spurred on by the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the subsequent resurgence of war those attacks inspired. -

Tenkiller State Park Resource Management Plan

Tenkiller State Park Resource Management Plan Sequoyah County, Oklahoma Hung-Ling (Stella) Liu, Ph.D. Lowell Caneday, Ph.D. I-Chun (Nicky) Wu, Ph.D. Tyler Tapps, Ph.D. This page intentionally left blank. Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge the assistance of numerous individuals in the preparation of this Resource Management Plan. On behalf of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department’s Division of State Parks, staff members were extremely helpful in providing access to information and in sharing of their time. The essential staff providing assistance for the development of the RMP included Lessley Pulliam, manager of Tenkiller State Park; Jim Sturges, park manager; Bryan Farmer, park ranger; and Leann Bunn, naturalist at Tenkiller State Park. Each provided insight from their years of experience at or in association with Tenkiller State Park. Assistance was also provided by Deby Snodgrass, Kris Marek, and Doug Hawthorne – all from the Oklahoma City office of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department. Greg Snider, northeast regional manager for Oklahoma State Parks, also assisted throughout the project. It is the purpose of the Resource Management Plan to be a living document to assist with decisions related to the resources within the park and the management of those resources. The authors’ desire is to assist decision-makers in providing high quality outdoor recreation experiences and resources for current visitors, while protecting the experiences and the resources for future generations. Lowell Caneday, Ph.D., Regents Professor Leisure Studies Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 74078 i Abbreviations and Acronyms ADAAG ................................................. Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines CDC ...................................................................................................... Centers for Disease Control CFR ..................................................................................................... -

Little Rock, Arkansas

LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS The civil works portion of this District covers an area of the District is responsible for the portion of the Little approximately 36,414 square miles in northern, western, River and its tributaries that are in the state of Arkansas, and southwestern Arkansas and a portion of Missouri. above its mouth near Fulton, AR. In the White River This area is within the Arkansas River, Little River, and Basin, the District is responsible for those portions in White River basins. In the Arkansas River Basin, the southern Missouri and northern and eastern Arkansas in District is responsible for planning, design, construction, the White River drainage basin and its tributaries above operation, and maintenance of the navigation portion of Peach Orchard Bluff, AR. The Memphis District is re- the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System sponsible for navigation maintenance on the White River (MKARNS). The District is also responsible for the ar- below Newport, AR, to the mouth of Wild Goose Bay- eas included in the Arkansas River drainage basin from ou, in Arkansas County, AR. The White River down- above Pine Bluff, AR, to below the mouth of the Poteau stream from the mouth of Wild Goose Bayou is part of River, near Fort Smith, AR. In Little River Basin, the MKARNS. IMPROVEMENTS NAVIGATION 1. Arkansas River Basin, AR, OK, And KS ........... 3 Multiple-Purpose Projects Including Power 2. Arthur V. Ormond Lock & Dam (No.9), AR ..... 4 3. David D. Terry Lock And Dam (No. 6), AR ...... 4 28. Beaver Lake, AR ………………………………9 4. Emmett Sanders Lock And Dam (No. -

To Purchase an Electronic, Downloadable Copy of This Issue

Cowboy Way Tribune Volume 3, Issue 3 Cowboy Way Cowboy Way Cowboy Way Crossroads & Jubilee Store LIVE Concerts Thursday, Your online source for Western, well, Saturday, October 7 everything! May 1, 2021 through • Cowboy Way Jubilee Noon to 7pm & Sunday, 7pm to 10:30pm October 10, Logo items & Gifts @ Fort Concho on the 2021 • Official James Drury Parade Grounds see website for times Photos Bring a Blanket or Chairs • 3rd Party Vendors to hear @ Fort Concho, Nation- al Historic Landmark Stephen Pride & Musicians: Kristyn Harris Experience a Modern It’s a great place to in concert Wild West event! 3 Days sell your CDs! of Celebrities, Music, Vendors Wanted! Film, Shopping, Food, & Artisans & Booths $25 Workshops! Store Owners Musicians Wanted! So much to do you’ll have Reach your target market “Open Mic” to come back year after with little effort for donations year! • Easy DIY Set up See our Article in • Email notification of Featured Register online: orders Events! www.CowboyWayJubilee.com • You ship (page 37) 52 g Everything ratin Cowbo Celeb y The Cowboy Way Tribune Pre story Tribune s i ervin e & H g Cowboy Cultur A Triannual Publication, Oleeta Jean, LLC, Publisher VOLUME 3, ISSUE 3 — EARLY SPRING 2021 Preserving Cowboy Culture & History! History Only Repeats — If We Refuse to Preserve the Past “A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots”. — Marcus Garvey NEARLY EVERYONE AGREES, 2020 was a year to forget, not a year we care to re-live. Certainly it had its challenges. And losses. -

Tuesday, February 11, 2020 at 9:00 Am Oklahom

AGENDA Oklahoma Wildlife Conservation Commission Regular Meeting Public Meeting: Tuesday, February 11, 2020 at 9:00 a.m. Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation 1801 N. Lincoln Blvd. Oklahoma City, OK 73105 The Commission may vote to approve, disapprove or take other action on any of the following items. The Commission may vote to authorize public comment on any agenda item requesting a rule change. 1. Call to Order – Chairman Bruce Mabrey 2. Roll Call – Rhonda Hurst 3. Invocation – Barry Bolton 4. Pledge of Allegiance – Barry Bolton 5. Introduction of Guests 6. Presentation of Awards – J.D. Strong, Director Dru Polk, Warden Supervisor – 20 years Presentation and recognition of the 2020 Governor’s Communication Effectiveness Award presented to the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation for efforts to promote awareness and participation in the Hunters Against Hunger program. Kelly Adams, Information and Education Specialist, took the lead in developing and executing the award- winning communication plan. 7. Consideration and vote to approve, amend, reject or take other action on minutes of the December 2, 2020 regular Commission meeting. 8. Presentation of the November 30 & December 31, 2019 Financial Statements and consideration and vote to approve, amend or reject miscellaneous donations – Amanda Stork, CFO and Chief of Administration. 9. Director's Report – J.D. Strong a. Federal and Congressional Update • Oklahoma Legislative Update – Corey Jager, Legislative Liaison b. Calendar Items – discussion of upcoming department calendar items. c. Agency Update – an update on current activity within each division of the agency. 10. Consideration and vote to approve, amend, reject or take other action on Permanent Rules – Barry Bolton, Chief of Fisheries Division. -

Murder, She Wrote (An Episode Guide)

Murder, She Wrote (an Episode Guide) Murder, She Wrote an Episode Guide by Jeff DeVouge Last updated: Tue, 26 Jul 2005 00:00 264 eps aired from: Sep 1984 to: May 1996 CBS 60 min stereo closed captioned 4 TVMs Full Titles 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th (BIG) List Season Season Season Season Season Season Season Season Season Season Season Season Guide regulars: ● Angela Lansbury as Jessica Fletcher recurring characters: ● William Windom as Doctor Seth Hazlett ● Tom Bosley as Sheriff Amos Tupper [ 1-4 ] ● Jerry Orbach as Harry McGraw [ 1-6 ] ● Michael Horton as Grady Fletcher [ 1-11 ] ● Richard Paul as Mayor Sam Booth [ 3-7 ] ● Julie Adams as Eve Simpson [ 4-9 ] ● Will Nye as Deputy Floyd [ 5-7 ] ● Keith Michell as Dennis Stanton [ 5-9 ] ● Ron Masak as Sheriff Mort Metzger [ 5-12 ] ● James Sloyan as Robert Butler [ 6-7 ] ● Ken Swofford as Lt. Perry Catalano [ 6-7 ] ● Hallie Todd as Rhoda Markowitz [ 6-7 ] ● Louis Herthum as Deputy Andy Broom [ 8-12 ] http://epguides.com/MurderSheWrote/guide.shtml (1 of 67) [14.08.2012 16:48:50] Murder, She Wrote (an Episode Guide) SEARCH Back to TO Title TO Next Related links Menus FAQ epguides TOP of Page List Season via Google & Grids & TV.com Pilot 1. "The Murder of Sherlock Holmes" cast: Eddie Barth [ Bernie ], Jessica Browne [ Kitty Donovan ], Bert Convy [ Peter Brill ], Herb Edelman [ Bus Driver ], Anne Lloyd Francis [ Louise McCallum ], Michael Horton [ Grady Fletcher ], Tricia O'Neil [ Ashley Vickers ], Dennis Patrick [ Dexter Baxendale ], Raymond St. Jacques [ Doctor ], Ned -

Arkansas-Oklahoma Arkansas River Compact Commission

Arkansas-Oklahoma Arkansas NTRODUCTION River Compact Commission I Environmental Committee Report September 24, 2020 INTRODUCTION This document is a compilation of data that has been collected within the Arkansas/Oklahoma Arkansas River Compact area. Items included for review; NTRODUCTION I Introduction Water Quality Trends at Different Flow Regimes OWRB Beneficial Use Monitoring Program - Streams/Rivers OWRB Beneficial Use Monitoring Program – Lakes/Reservoirs Compact Waters included in the Oklahoma Water Quaity Integrated Report – 303(d) Water Quality Standards Revisions Relevant to the Arkansas-Oklahoma Compact Commission Area TMDL’s Completed in the Compact Area Oklahoma’s Phosphorus Loading Report for the Illinois River Basin Funding Provided by OWRB’s Financial Assistance Program Permits Issued for Water Rights in the Illinois River Watershed Oklahoma Conservation Commission Efforts in the Illinois River Watershed Table 1. Comparison of geometric means to the Oklahoma Scenic River total phosphorus criterion calculated from 1999-20191 and 2014-2019. 1999-2019 (3-month GM'S) 2014-2019 (3-month GM'S) Station (see footnotes) N N< % Exceeding N N< % Exceeding NTRODUCTION (Period) 0.037 0.037 (Period) 0.037 0.037 I Illinois River near Watts2 335 11 97% 63 5 92% Illinois River near Tahlequah2 336 23 93% 63 11 83% Flint Creek near Kansas2 327 0 100% 63 0 100% Barren Fork near Eldon2 327 193 41% 66 50 24% Little Lee Creek near Nicut1 110 108 2% 44 44 0% Lee Creek near Short 226 225 0% 47 47 0% Mountain Fork River near 197 167 15% 46 42 9% -

Title Catalog Link Section Call # Summary Starring 28 Days Later

Randall Library Horror Films -- October 2009 Check catalog link for availability Title Catalog link Section Call # Summary Starring 28 days later http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. DVD PN1995.9. An infirmary patient wakes up from a coma to Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris, edu/record=b1917831 Horror H6 A124 an empty room ... in a vacant hospital ... in a Christopher Eccleston, Megan Burns, 2003 deserted city. A powerful virus, which locks Brendan Gleeson victims into a permanent state of murderous rage, has transformed the world around him into a seemingly desolate wasteland. Now a handful of survivors must fight to stay alive, 30 days of night http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. DVD PN1995.9. An isolated Alaskan town is plunged into Josh Hartnett, Melissa George, Danny edu/record=b2058882 Horror H6 A126 darkness for a month each year when the sun Huston, Ben Foster, Mark Boone, Jr., 2008 sinks below the horizon. As the last rays of Mark Rendall, Amber Sainsbury, Manu light fade, the town is attacked by a Bennett bloodthirsty gang of vampires bent on an uninterrupted orgy of destruction. Only the town's husband-and-wife Sheriff team stand 976-EVIL http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. VHS PN1995.9. A contemporary gothic tale of high-tech horror. Stephen Geoffreys, Sandy Dennis, edu/record=b1868584 Horror H6 N552 High school underdog Hoax Wilmoth fills up Lezlie Deane 1989 the idle hours in his seedy hometown fending off the local leather-jacketed thugs, avoiding his overbearing, religious fanatic mother and dreaming of a date with trailer park tempress Suzie. But his quietly desperate life takes a Alfred Hitchcock's http://uncclc.coast.uncwil.