Celtic Mythology in the Arthurian Legend Master’S Diploma Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish Narrative Literature with Particular Reference to Tales Belonging to the Ulster Cycle

The role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish narrative literature with particular reference to tales belonging to the Ulster Cycle. Mary Leenane, B.A. 2 Volumes Vol. 1 Ph.D. Degree NUI Maynooth School of Celtic Studies Faculty of Arts, Celtic Studies and Philosophy Head of School: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn Supervisor: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn June 2014 Table of Contents Volume 1 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I: General Introduction…………………………………………………2 I.1. Ulster Cycle material………………………………………………………...…2 I.2. Modern scholarship…………………………………………………………...11 I.3. Methodologies………………………………………………………………...14 I.4. International heroic biography………………………………………………..17 Chapter II: Sources……………………………………………………………...23 II.1. Category A: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a significant role…………...23 II.2. Category B: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a more limited role………...41 II.3. Category C: Texts in which Cú Chulainn makes a very minor appearance or where reference is made to him…………………………………………………...45 II.4. Category D: The tales in which Cú Chulainn does not feature………………50 Chapter III: Cú Chulainn’s heroic biography…………………………………53 III.1. Cú Chulainn’s conception and birth………………………………………...54 III.1.1. De Vries’ schema………………...……………………………………………………54 III.1.2. Relevant research to date…………………………………………………………...…55 III.1.3. Discussion and analysis…………………………………………………………...…..58 III.2. Cú Chulainn’s youth………………………………………………………...68 III.2.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………68 III.2.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………69 III.2.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..78 III.3. Cú Chulainn’s wins a maiden……………………………………………….90 III.3.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………90 III.3.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………91 III.3.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..95 III.3.4 Further comment……………………………………………………………………...108 III.4. -

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

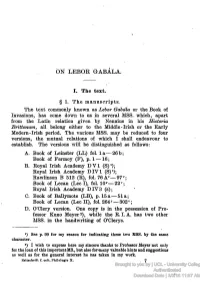

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell

Theosophical University Press Online Edition The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell Copyright © 1914 by Katherine Tingley; originally published at Point Loma, California. Electronic edition 2000 by Theosophical University Press ISBN 1- 55700-157-x. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. For ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in the electronic version of the text. To Katherine Tingley: Leader and Official Head of the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society, whose whole life has been devoted to the cause of Peace and Universal Brotherhood, this book is respectfully dedicated Contents Preface The Three Branches of the Bringing-in of it, namely: The Sovereignty of Annwn I. The Council of the Immortals II. The Hunt in Glyn Cuch III. The Slaying of Hafgan The Story of Pwyll and Rhianon, or The Book of the Three Trials The First Branch of it, called: The Coming of Rhianon Ren Ferch Hefeydd I. The Making-known of Gorsedd Arberth, and the Wonderful Riding of Rhianon II. The First of the Wedding-Feasts at the Court of Hefeydd, and the Coming of Gwawl ab Clud The Second Branch of it, namely: The Basket of Gwaeddfyd Newynog, and Gwaeddfyd Newynog Himself I. The Anger of Pendaran Dyfed, and the Putting of Firing in the Basket II. The Over-Eagerness of Ceredig Cwmteifi after Knowledge, and the Putting of Bulrush-Heads in the Basket III. The Circumspection of Pwyll Pen Annwn, and the Filling of the Basket at Last The First Branch of it again: III. -

Arawn Celtic God of the Otherworld

Samhain ~ Full Moon in Scorpio 12th May 2017 On this night we will be connecting to the energy of the Scorpio Full Moon under the guidance of the God Arawn Celtic God of the Otherworld. This is the time of the year when the boundary is thinnest between the worlds of the living and the dead. The powers of divination, the Sight, and supernatural communication are stronger over this period and it is considered a potent time to communicate with those that inhabit the Other Worlds. Sydney Ritual Introduction Scorpio Full Moon: Scorpio energy is all about transformation and reaching higher levels of consciousness. In fact, Scorpio energy has the potential to reach Divine levels of consciousness, but at the same time, it also has the ability to reach extremely low levels of consciousness as well. No matter where you fall on the “consciousness spectrum” it is likely that this Full Moon is going to leave a lasting impact. It is also likely that this Full Moon is going to help open your consciousness to a new level so you can see things in a different light. Things may feel a little uneasy as changes may be in the air, but the best way to manage this energy moving forward is remembering your personal power. Very often we forget that we have a strength and power within us. This power gives us the ability to step up and take responsibility over our lives no matter what troubles woe find ourselves in. The minute we give away our power, it becomes very difficult to deal with the situations that life throws our way. -

The Heroic Biography of Cu Chulainn

THE HEROIC BIOGRAPHY OF CU CHULAINN. By Lisa Gibney B.A. NUl MAYNOOTH Ollicoil ni ft£ir«ann Mi ftuid FOR M.A IN MEDIEVAL IRISH HISTORY AND SOURCES, NUI MAYNOOTH, THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIEVAL IRISH STUDIES, JULY 2004. DEPARTMENT HEAD: MCCONE, K SUPERVISOR: NI BHROLCHAIN,M 60094838 THE HEROIC BIOGRAPHY OF CU CHULAINN. By Lisa Gibney B.A. SPECIAL THANKS TO: Ann Gibney, Claire King, Mary Lenanne, Roisin Morley, Muireann Ni Bhrolchain, Mary Coolen and her team at the Drumcondra Physiotherapy Clinic. CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2 2. Heroic Biography 8 3. Conception and Birth: Compert Con Culainn 18 4. Youth and Life Endangered: Macgnimrada 23 Con Culainn 5. Acquires a wife: Tochmarc Emere 32 6. Visit to Otherworld, Exile and Return: 35 Tochmarc Emere and Serglige Con Culainn 7. Death and Invulnerability: Brislech Mor Maige 42 Muirthemne 8. Conclusion 46 9. Bibliogrpahy 47 i INTRODUCTION Early Irish literature is romantic, idealised, stylised and gruesome. It shows a tension between reality and fantasy ’which seem to me to be usually an irresolvable dichotomy. The stories set themselves in pre-history. It presents these texts as a “window on the iron age”2. The writers may have been Christians distancing themselves from past heathen ways. This backward glance maybe taken from the literature tradition in Latin transferred from the continent and read by Irish scholars. Where the authors “undertake to inform the audience concerning the pagan past, characterizing it as remote, alien and deluded”3 or were they diligent scholars trying to preserve the past. This question is still debateable. The stories manage to be set in both the past and the present, both historical Ireland with astonishingly accuracy and the mythical otherworld. -

Double-Consciousness in the Work of Dylan Thomas

University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2011 ‘One Foot in Wales and My Vowels in England’: Double-Consciousness in the work of Dylan Thomas Karl Powell University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The am terial in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Powell, K. (2011). ‘One Foot in Wales and My Vowels in England’: Double-Consciousness in the work of Dylan Thomas (Honours). University of Notre Dame Australia. http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/69 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter One: ‘To Begin at the Beginning’ Be thou silent, As to the name of thy verse, And to the name of thy vaunting; And as to the name of thy grandsire Prior to his being baptised. And the name of the sphere, And the name of the element, And the name of thy language, And the name of thy region. Avaunt, ye bards above, Avaunt, ye bards below! - The Reproof of the Bards (Taliesin) Sometimes it seems our lives are already somehow mapped out for us. Almost like Sophocles’ great tragedy, Oedipus Rex, where we see the forces of Fate pitted against the human condition, it can feel as if external factors play a crucial role in determining who we are.32 Take for example the names given to Dylan Thomas. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 The aW rped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J. Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, M. J.(2019). The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5278 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth By Martha J. Lee Bachelor of Business Administration University of Georgia, 1995 Master of Arts Georgia Southern University, 2003 ________________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Ed Madden, Major Professor Scott Gwara, Committee Member Thomas Rice, Committee Member Yvonne Ivory, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Martha J. Lee, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation and degree belong as much or more to my family as to me. They sacrificed so much while I traveled and studied; they supported me, loved and believed in me, fed me, and made sure I had the time and energy to complete the work. My cousins Monk and Carolyn Phifer gave me a home as well as love and support, so that I could complete my course work in Columbia. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

Gwern in the Fire 2006

Caer Australis Occasional Papers : Gwern in the Fire 2006 Gwern in the Fire By John Bonsing The Second Branch of the Mabinogi holds the story of the burning of Branwen's son, Gwern, in a great fire prepared at a feast arranged to settle a raid upon Ireland by the troops of Britain. The story comes down to us from the compilations of the the White Book of Rhydderch (1325) and the Red Book of Hergest (1400) whose contents comprise redactions of earlier mythological material. What is remarkable is that the story of Gwern in the fire bears a striking similarity to the traditions of the Beltaine fire customs recorded in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by Thomas Pennant, John Ramsey and Walter Gregor in the Highlands and Islands. Intimately involved is a cauldron of rebirth, and this magical cauldron appears throughout Celtic myth and poetry of both Ireland and Wales, as well as featuring in the famous Gundestup cauldron that dates from the first century. Presented below are these three occurrences of the motif, giving us glimpses of this ancient Beltaine story. The burning of Gwern in the Fire And the men of the Island of Ireland came into the house on the one side, and the men of the Island of the Mighty on the other. And as soon as they were seated there was concord between them, and the kingship conferred upon the boy, Gwern son of Matholwch king of the Island of Ireland by Branwen daughter of Llŷr, sister of Bendigeidfran son of Llŷr, king of the Island of the Mighty.