September 10, 2012, Ptsd Newsletter #2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intelligence Digest | Middle East 4-10 November 2012

Intelligence Digest | Middle East 4-10 November 2012 Afghanistan Victims and relatives to testify in trial of US soldier accused of killing 16 Afghan civilians New York Times, 9 November: T o victims and four victims' relatives ill testify Friday from Afghanistan, via videoconference and through a translator, in an overnight session of the pre-trial hearing for Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, ho allegedly murdered 16 Afghan civilians in t o villages in March. nydailyne s.com/ne s/ orld/victims-testify-afghan-massacre-case-article- 1.11,,3.0 Afghan-Pakistan meeting to discuss resuming negotiations with the Afghan aliban Express Tribune, 9 November: Afghan and Pa0istani officials ill hold tal0s in 1slamabad ne2t ee0 on restarting negotiations ith the Afghan Taliban, mar0ing Salahuddin Rabbani's first visit to Pa0istan since the 0illing of his father and predecessor as head of Afghanistan's 3igh Peace Council, Burhanuddin Rabbani. tribune.com.p0/story/463060/pa0istan-afghanistan-to-revive-tal0s- ith- taliban/ Afghanistan bomb attacks "kill 20" BBC, 8 November: At least 20 people, including 12 civilians, have been 0illed in four separate militant attac0s in Afghanistan, officials say. 5omen and children ere among 10 0illed hen a minibus hit a roadside bomb in southern 3elmand province. Other bombings 0illed five Afghan soldiers in 6aghman in the east, three police in 7andahar and t o boys in 8abul province. bbc.co.u0/ne s/ orld-asia-20248632 Afghanistan welcomes UN designation of Haqqani Network as terrorists and rules out negotiations Reuters, 6 November: Afghanistan's presidential spo0esman elcomed the :nited Nations' designation of the 3aqqani Net or0 as a terrorist organization on Tuesday, and said the government ould not negotiate ith the group. -

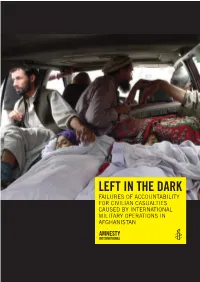

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Shawn Cupp and Aimee Bateman, What Is Life Worth Abstract And

What is Life Worth in the United States Army Military Justice System? MAJ Aimee M. Bateman, J.D., Texas Tech School of Law CGSOC Student O. Shawn Cupp, Ph.D., Kansas State University Professor US Army Command and General Staff College ATTN: Department of Logistics and Resource Operations (DLRO) Room 2173B 100 Stimson Avenue Fort Leavenworth, KS 66027 Voice: 913.684.2983 Fax: 913.684.2927 [email protected] [email protected] Authors’ Financial Disclosure – We have no conflict of interest, including direct or indirect financial interest that is included in the materials contained or related to the subject matter of this manuscript. Disclaimer: The views and conclusions expressed in the context of this document are those of the author developed in the freedom of expression, academic environment of the US Army Command and General Staff College. They do not reflect the official position of the US Government, Department of Defense, United States Department of the Army, or the US Army Command and General Staff College. ABSTRACT What is Life Worth in the U.S. Army Military Justice System? by Aimee M. Bateman, MAJ and O. Shawn Cupp, Ph.D., (LTC, retired, US Army) This paper explores the value of human life as viewed through the lens of contemporary U.S. Army military justice, specifically the results of the U.S. Army Clemency and Parole Board (ACPB). The current operational environment and soldiers convicted of committing Article 118 (Murder) while deployed provides the bounded framework for the cases within this study. The research problem is the perceived difference in adjudication of U.S. -

The Broken Promises of an All-Volunteer Military

THE BROKEN PROMISES OF AN ALL-VOLUNTEER MILITARY * Matthew Ivey “God and the soldier all men adore[.] In time of trouble—and no more, For when war is over, and all things righted, God is neglected—and the old soldier slighted.”1 “Only when the privileged classes perform military service does the country define the cause as worth young people’s blood. Only when elite youth are on the firing line do war losses become more acceptable.”2 “Non sibi sed patriae”3 INTRODUCTION In the predawn hours of March 11, 2012, Staff Sergeant Robert Bales snuck out of his American military post in Kandahar, Afghanistan, and allegedly murdered seventeen civilians and injured six others in two nearby villages in Panjwai district.4 After Bales purportedly shot or stabbed his victims, he piled their bodies and burned them.5 Bales pleaded guilty to these crimes in June 2013, which spared him the death penalty, and he was sentenced to life in prison without parole.6 How did this former high school football star, model soldier, and once-admired husband and father come to commit some of the most atrocious war crimes in United States history?7 Although there are many likely explanations for Bales’s alleged behavior, one cannot help but to * The author is a Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy. This Article does not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, the United States Navy, or any of its components. The author would like to thank Michael Adams, Jane Bestor, Thomas Brown, John Gordon, Benjamin Hernandez- Stern, Brent Johnson, Michael Klarman, Heidi Matthews, Valentina Montoya Robledo, Haley Park, and Gregory Saybolt for their helpful comments and insight on previous drafts. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Kansas

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS ROBERT BALES, Petitioner, v. CASE NO. 19-3112-JWL COMMANDANT, U.S. Disciplinary Barracks, Respondent. MEMORANDUM AND ORDER This matter is a petition for habeas corpus filed under 28 U.S.C. § 2241. Petitioner is confined at the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Petitioner seeks to set aside his 2013 convictions by general court-martial. Because the military courts fully and fairly reviewed all of Petitioner’s claims, the petition for habeas corpus must be denied. I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND Petitioner, a former active duty member of the United States Army, was convicted by general court-martial at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington. The Army Court of Criminal Appeals (“ACCA”) summarized the underlying facts as follows: Appellant was deployed to Afghanistan and was stationed at VSP Belambay. In the early morning hours of 11 March 2012, appellant left VSP Belambay and travelled to the village of Alikozai. Appellant was armed with his M4 rifle, H&K 9 millimeter pistol, advance combat helmet with night vision device, one full magazine containing thirty 5.56mm rounds for his M4 and one magazine containing fifteen 9mm rounds for his H&K pistol. While in Alikozai, appellant killed four people by shooting them at close range, which included two elderly men, one elderly woman and one child. Appellant also assaulted six people, which included one woman and four children. 1 When appellant ran low on ammunition, he returned to VSP Belambay to obtain additional ammunition. Appellant left VSP Belambay for a second time, this time armed with his M4 rifle, 9mm H&K pistol, M320 grenade launcher with accompanying ammunition belt, night vision device and ammunition for all of his weapons. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States Robert Bales, Petitioner, V

No 17 - In The Supreme Court of the United States Robert Bales, Petitioner, v. United States, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI JOHN N. MAHER* KEVIN J. MIKOLASHEK DAVID G. BOLGIANO MAHER LEGAL SERVICES PC 7 EAST MAIN STREET, NUMBER 1053 ST. CHARLES, ILLINOIS 60174 [email protected] (708) 468-8155 May 16, 2018 *Counsel of Record LEGAL PRINTERS LLC, Washington DC ! 202-747-2400 ! legalprinters.com QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW Whether the Court of Appeals erred when it held that in a capital case, a prosecutor does not have to disclose exculpatory medical evidence in the government’s possession relating to the accused’s state-of-mind to commit 16 homicides where the United States ordered the accused to take mefloquine, a drug known by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Military to cause long-lasting adverse psychiatric effects, including symptoms of psychosis that may occur years after use. Whether the Court of Appeals erred when it held that in a capital case, a prosecutor does not have to disclose mitigating impeachment evidence in the government’s possession that Afghan sentencing witnesses flown into the United States left their fingerprints on bombs and improvised explosive devices, especially where the prosecution held the Afghan witnesses out to the jury as innocent “farmers.” i PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING AND RULE 29.6 STATEMENT Petitioner is Robert Bales, appellant below. Respondent is the United States, appellee below. Petitioner is not a corporation. -

ICC-02/17 Date: 20 November 2017 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before

ICC-02/17-7-Red 20-11-2017 1/181 NM PT ras Original: English No.: ICC-02/17 Date: 20 November 2017 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Antoine Kesia-Mbe Mindua, Presiding Judge Judge Chang-ho Chung Judge Raul C. Pangalangan SITUATION IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGHANISTAN PUBLIC with confidential, EX PARTE, Annexes 1, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, 4A, 4B, 4C, 6, public Annexes 4, 5 and 7, and public redacted version of Annex 1-Conf-Exp Public redacted version of “Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15”, 20 November 2017, ICC-02/17-7-Conf-Exp Source: Office of the Prosecutor ICC-02/17-7-Red 20-11-2017 2/181 NM PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Mrs Fatou Bensouda Mr James Stewart Mr Benjamin Gumpert Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Defence Support Section Mr Herman von Hebel Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Mr Nigel Verrill No. ICC- 02/17 2/181 20 November 2017 ICC-02/17-7-Red 20-11-2017 3/181 NM PT I. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 6 II. Confidentiality ................................................................................................. -

How the United States Charges Its Service Members for Violating The

Military Self-Interest in Accountability for Core International Crimes Morten Bergsmo and SONG Tianying (editors) PURL: http://www.legal-tools.org/doc/31da70/ E-Offprint: Christopher Jenks, “Self-Interest or Self-Inflicted? How the United States Charges Its Service Members for Violating the Laws of War”, in Morten Bergsmo and SONG Tianying (editors), Military Self-Interest in Accountability for Core International Crimes, FICHL Publication Series No. 25 (2015), Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, Brussels, ISBN 978-82-93081-81-4. First published on 29 May 2015. This publication and other TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the website www.fichl.org. This site uses Persistent URLs (PURL) for all publications it makes available. The URLs of these publications will not be changed. Printed copies may be ordered through online distributors such as www.amazon.co.uk. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2015. All rights are reserved. PURL: http://www.legal-tools.org/doc/31da70/ 12 ______ Self-Interest or Self-Inflicted? How the United States Charges Its Service Members for Violating the Laws of War Christopher Jenks* 12.1. Introduction In the early morning of 11 March 2012, a US service member, Staff Ser- geant Robert Bales, slipped undetected from Village Stability Platform (‘VSP’) Belambai about 30 kilometres from Kandahar, Afghanistan. Bales was one of approximately 40 US military personnel deployed to VSP Belambai. Their mission was “to assist the Afghan government in maintaining security, reconstructing the country, training the national po- lice and army, and providing a lawful environment for free and fair elec- tions”.1 Sergeant Bales, however, was on a very different mission. -

War on Terror – Lessons from Lincoln

LINCOLN MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW __________________________________ VOLUME 1 DECEMBER 2013 ISSUE 1 _____________________________________ WAR ON TERROR – LESSONS FROM LINCOLN M. Akram Faizer * INTRODUCTION On May 1, 2012, President Obama announced that U.S. forces would continue their phased withdrawal from Afghanistan such that by the end of 2014, Afghan security forces will have full responsibility for their country’s security. 1 Of particular note, the President’s speech was directed solely at an American audience with very little attention paid to either Afghan sentiment or the Afghan people’s needs. The unidirectional nature of the President’s focus was inadvertently evidenced when, on Afghan soil, he closed the speech by stating: * Assistant Professor of Law, Lincoln Memorial University-Duncan School of Law. The author would like to dedicate this piece to his darling Melanie. 1 See Mark Landler, Obama Signs Pact in Kabul, Turning Page in Afghan War , N.Y. TIMES , May 2, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/02/world/ asia/obama-lands-in-kabul-on-unannounced- visit.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0; see also David E. Sanger, Charting Obama’s Journey to a Shift on Afghanistan , N.Y. TIMES , May 20, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/20/us/obamas-journey-to-reshape- afghanistan-war.html?hp. 14 1 LMU LAW REVIEW 1 (2013) “May God bless our troops and may God bless the United States of America.” 2 The President’s words did not evidence any acknowledgement that an expression of American solicitude for Afghan well-being might equally be in the American people’s interests. -

The Right to Heal U.S

The Right to Heal U.S. Veterans and Iraqi Organizations Seek Accountability for Human Rights and Health Impacts of Decade of U.S.-led War Preliminary Report Submitted in Support of Request for Thematic Hearing Before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 149th Period of Sessions Supplemented and Amended Submitted by The Center for Constitutional Rights on behalf of Federation of Workers Councils and Unions in Iraq Iraq Veterans Against the War Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Pam Spees, Rachel Lopez, and Maria LaHood, with the assistance of Ellyse Borghi, Yara Jalajel, Jessica Lee, Jeena Shah, Leah Todd and Aliya Hussain. We are grateful to Adele Carpenter and Drake Logan of the Civilian-Soldier Alliance who provided invaluable research and insights in addition to the testimonies of servicemembers at Fort Hood and to Sean Kennedy and Brant Forrest who also provided invaluable research assistance. Deborah Popowski and students working under her supervision at Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic contributed early research with regard to the framework of the request as well as on gender-based violence. Table of Contents Submitting Organizations List of Abbreviations and Acronyms I. Introduction: Why This Request? 1 Context & Overview of U.S.’s Decade of War and Its Lasting Harms to Civilians and Those Sent to Fight 2 U.S.’s Failure / Refusal to Respect, Protect, Fulfill Rights to Life, Health, Personal Security, Association, Equality, and Non-Discrimination 2 Civilian -

Exploring the Dramatization in Dabiq: a Fantasy Theme Analysis

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF John G. Drischell for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Speech Communication, Speech Communication, and Philosophy presented on June 12, 2017. Title: Exploring the Dramatization in Dabiq: A Fantasy Theme Analysis Abstract approved: _________________________________________ Gregg B. Walker The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) is a formidable international force operating and perpetuating religious, military, and violent agendas. In 2014, ISIS established a worldwide Caliphate governing religious authority across Middle Eastern territories. ISIS operations are grandiose and large scale, longevity and survival are predicated on recruitment. One prominent ISIS recruiting tool is a printed and digitally produced magazine. Entitled Dabiq, the magazine represents the motives and ideologies behind ISIS; it symbolizes what ISIS hopes to accomplish. Dabiq includes powerful imagery and persuasive statements to draw readers in. The most cogent and dramatized elements in Dabiq reveal persuasion strategies. This study uses a rhetorical criticism; Fantasy Theme Analysis is the methodology chosen to examine the Dabiq series. The concepts of fantasy themes, fantasy types, master analogies, and rhetorical visions are considered to explore elements in Dabiq. ©Copyright by John G. Drischell June 12, 2017 All Rights Reserved Exploring the Dramatization in Dabiq: A Fantasy Theme Analysis by John G. Drischell A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University -

Military Jurisdiction and the Decision to Seek the Death Penalty Clark Smith

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review 7-1-2015 Fair and Impartial? Military Jurisdiction and the Decision to Seek the Death Penalty Clark Smith Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umnsac Part of the Military, War and Peace Commons, and the National Security Commons Recommended Citation Clark Smith, Fair and Impartial? Military Jurisdiction and the Decision to Seek the Death Penalty, 5 U. Miami Nat’l Security & Armed Conflict L. Rev. 1 (2015) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umnsac/vol5/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fair and Impartial? Military Jurisdiction and the Decision to Seek the Death Penalty Clark Smith* When thepunishment maybedeath, there are particular reasons to ensure that the menandwomen of the ArmedForces do not by reason of serving their countryreceive less protection than theConstitution provides for civilians.1 - John Paul Stevens Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 2 II. CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE MILITARY.......................................... 6 A. Brief History.................................................................................