Provincializing Spotify: Radio, Algorithms and Conviviality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D6.1 Feedback on #Musicbricks from the Industry Testbed

Project Acronym: MusicBricks Project Full Title: Musical Building Blocks for Digital Makers and Content Creators Grant Agreement: N°644871 Project Duration: 18 months (Jan. 2015 - June 2016) D6.1 Feedback on #MusicBricks from the Industry Testbed Deliverable Status: Final File Name: MusicBricks_D6.1.pdf Due Date: Jan 2016 (M13) Submission Date: Jan 2016 (M13) Dissemination Level: Public Task Leader: TU WIEN Authors: Thomas Lidy (TU WIEN), Jordi Janer (UPF), Sascha Grollmisch (Fraunhofer), Frederic Bevilacqua (Ircam), Emmanuel Flety (Ircam), Marta Arniani (Sigma Orionis), Michela Magas (Stromatolite) ! This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement n°644871 The #MusicBricks project consortium is composed of: SO Sigma Orionis France STROMATOLITE Stromatolite Ltd UK IRCAM Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique Musique France UPF Universitat Pompeu Fabra Spain Fraunhofer Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft zur Foerderung der Angewandten Forschung E.V Germany TU WIEN Technische Universitaet Wien Austria Disclaimer All intellectual property rights are owned by the #MusicBricks consortium members and are protected by the applicable laws. Except where otherwise specified, all document contents are: “©MusicBricks Project - All rights reserved”. Reproduction is not authorised without prior written agreement. All #MusicBricks consortium members have agreed to full publication of this document. The commercial use of any information contained in this document may require a license from the owner of that information. All #MusicBricks consortium members are also committed to publish accurate and up to date information and take the greatest care to do so. However, the #MusicBricks consortium members cannot accept liability for any inaccuracies or omissions nor do they accept liability for any direct, indirect, special, consequential or other losses or damages of any kind arising out of the use of this information. -

Return of Private Foundation CT' 10 201Z '

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirem M11 For calendar year 20 11 or tax year beainnina . 2011. and ending . 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (212) 733-4250 235 EAST 42ND STREET City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here • • • • • . NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D q 1 . Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name change computation . 10. H Check type of organization' X Section 501( exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation q 19 under section 507(b )( 1)(A) , check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other ( specify ) ---- -- ------ ---------- under section 507(b)(1)(B),check here , q 205, 8, 166. 16) ► $ 04 (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The (d) Disbursements total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable may not necessanly equal the amounts in expenses per income income Y books purposes C^7 column (a) (see instructions) .) (cash basis only) I Contribution s odt s, grants etc. -

Warburton, John Henry. (2010). Picture Radio

! ∀# ∃ !∃%& ∋ ! (()(∗( Picture Radio: Will pictures, with the change to digital, transform radio? John Henry Warburton Master of Philosophy Southampton Solent University Faculty of Media, Arts and Society July 2010 Tutor Mike Richards 3 of 3 Picture Radio: Will pictures, with the change to digital, transform radio? By John Henry Warburton Abstract This work looking at radio over the last 80 years and digital radio today will consider picture radio, one way that the recently introduced DAB1 terrestrial digital radio could be used. Chapter one considers the radio history including early picture radio and television, plus shows how radio has come from the crystal set, with one pair of headphones, to the mains powered wireless with built in speakers. These radios became the main family entertainment in the home until television takes over that role in the mid 1950s. Then radio changed to a portable medium with the coming of transistor radios, to become the personal entertainment medium it is today. Chapter two and three considers the new terrestrial digital mediums of DAB and DRM2 plus how it works, what it is capable of plus a look at some of the other digital radio platforms. Chapter four examines how sound is perceived by the listener and that radio broadcasters will need to understand the relationship between sound and vision. We receive sound and then make pictures in the mind but to make sense of sound we need codes to know what it is and make sense of it. Chapter five will critically examine the issues of commercial success in radio and where pictures could help improve the radio experience as there are some things that radio is restricted to as a sound only medium. -

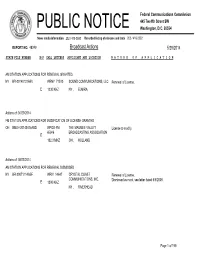

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

A – Z Internet Resources for Education A

A – Z Internet Resources for Education A o Acapela.tv is a fun site to create text-to-speech animations. o Alice is a 3D programming environment that makes it easy to create an animation for telling a story, playing an interactive game, or a video to share on the web. Alice is a teaching tool for introductory computing. It uses 3D graphics and a drag-and-drop interface to facilitate a more engaging, less frustrating first programming experience. o Animoto.com is a web application that produces professional quality videos from your pictures and music. o Audacity is a programme that allows you to record sounds straight to your computer (you do need a microphone) and edit them afterwards. Very popular with languages teachers and podcasters. o Audioboo is an audio-blogging site, you can send in updates through the web, phone or its own iPhone app. Perfect for blogging on the move, like on a school-trip, or sharing your class’s opinion about a topic. o authorSTREAM allows you to publish and share your PowerPoint presentations. It also allows you to download published presentations as videos. o Aviary is a suite of web applications which allow you to create, edit and manipulate images. They have also recently launched an audio editing tool called Myna (see below). B o BeFunky is a website that allows you to apply a variety of fun effects to your own photos or from photo sharing sites. o Big Huge Labs is a collection of utilities and toys that allow you to edit and alter digital pictures. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism. -

WAXY, WKIS, WLYF, WMXJ, WPOW, WQAM, WSFS EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT October 1, 2019 - September 30, 2020

Page: 1/24 WAXY, WKIS, WLYF, WMXJ, WPOW, WQAM, WSFS EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT October 1, 2019 - September 30, 2020 ENTERCOM Miami-Ft.Lauderdale-Hollywood,FL IS AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY EMPLOYER. Address: Contact Person/Title: 20450 NW Second Ave, Keriann Worley Miami, FL - 33169 SVP/Market Manager Telephone Number: E-Mail Address: 305-521-5100 [email protected] I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Account Executive 1-3, 6-26, 28-46, 48-91, 93-94, 96, 101 96 Promotions Manager 1-37, 39-48, 50-77, 80-91, 93, 95-96 96 Promotions Manager 1-37, 39-48, 50-77, 80-91, 93, 95-96 96 Digital Sales Manager 1-4, 6-41, 43-75, 77-91, 93, 96, 99 96 1-4, 6-33, 35-37, 39-41, 43-46, 48-77, Account Executive 96 79-91, 93, 96, 99-100 1-4, 6-33, 35-37, 39-41, 43-46, 48-77, Account Executive 30 79-91, 93, 96, 99-100 Account Executive 1-4, 6-31, 33-41, 43-62, 64-93, 96-99 96 Page: 2/24 WAXY, WKIS, WLYF, WMXJ, WPOW, WQAM, WSFS EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT October 1, 2019 - September 30, 2020 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") a. Agencies Notified by Outreach Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period African American Chamber of Commerce 3201 E. -

Beats (Review)

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Michael Schwartz Library Publications Michael Schwartz Library 7-2014 Beats (Review) Mandi Goodsett Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/msl_facpub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the Music Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Publisher's Statement This is an Author’s Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Music Reference Services Quarterly July/Sept 2014, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/ 10588167.2014.932147. Repository Citation Goodsett, Mandi, "Beats (Review)" (2014). Michael Schwartz Library Publications. 106. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/msl_facpub/106 This E-Resource Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michael Schwartz Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michael Schwartz Library Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. E-Resources Reviews BEATS MUSIC, http://www.beatsmusic.com For the past decade, the music industry has been attempting to provide lis- teners with legal, convenient ways to access music, competing with sites like Napster and its successors. In an attempt to pull consumers out of the illegal music free-for-all and into a fee-based streaming service, the music industry has fueled a sudden explosion of new mobile and desktop music streaming applications to satisfy the needs of digital-music consumers affordably and conveniently. Moving from streaming radio services like Pandora, the new on-demand music streaming services like Spotify, Rdio, Google Play All Access, and Rhapsody offer listeners a higher level of control and greater ability to curate a listening experience than ever before. -

Bomb Threat Suspect Found

Researcher receives science El Gallo de Oro lacks CMU students perform at contribution award • A4 drastic changes • A6 FringeNYC • B8 SCITECH FORUM PILLBOX thetartan.org @thetartan August 27, 2012 Volume 107, Issue 2 Carnegie Mellon’s student newspaper since 1906 Bomb Hunt Library gets new layout Wheels on bus to threat keep going round MADELYN GLYMOUR membership ratified it by a News Editor 10-to-one margin, and the suspect reason they ratified it by that The Port Authority an- margin was because of that nounced last Tuesday that the language.” found service reduction planned for Palonis pointed to Allegh- Sept. 2 would be postponed eny County Executive Rich JUSTIN MCGOWN until at least August 2013. Fitzgerald as another pivotal Staffwriter The postponement is the player in the agreement. result of a deal reached by “He really kept our nose The FBI officially in- the Port Authority, Allegh- to the grindstone throughout dicted Adam Stuart Busby eny County, Governor Tom this process,” Palonis said. on Aug. 22 for sending over Corbett’s office, and the Lo- “Rich is an advocate for trans- 40 threatening emails to the cal 85 Amalgamated Transit portation. I’ve dealt with a lot University of Pittsburgh last Union. Under the deal, Port of politicians through this year. Busby’s emails were Authority employees in the process, but Rich really wants part of a series of over 100 Local 85 union will undergo to see transportation grow.” bomb threats issued to Pitt a two-year pay freeze and According to the Pitts- throughout the spring se- increase the percentage of burgh Post-Gazette, Fitzger- mester. -

Settin' My Dial on the Radio

SETTIN ’ MY DIAL ON THE RADIO BOB DYLAN 2006 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES , NEW RELEASES , RECORDINGS & BOOKS . © 2010 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Settin’ My Dial On The Radio — Bob Dylan 2006 page 2 of 86 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................................4 2 2006 AT A GLANCE ..............................................................................................................................................................4 3 THE 2006 CALENDAR ..........................................................................................................................................................4 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ..............................................................................................................................6 4.1 MODERN TIMES ................................................................................................................................................................6 4.2 BLUES ..............................................................................................................................................................................6 4.3 THEME TIME RADIO HOUR : BASEBALL ............................................................................................................................8 -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Radio Airplay and the Record Industry: an Economic Analysis

Radio Airplay and the Record Industry: An Economic Analysis By James N. Dertouzos, Ph.D. For the National Association of Broadcasters Released June 2008 Table of Contents About the Author and Acknowledgements ................................................................... 3 Executive Summary....................................................................................................... 4 Introduction and Study Overview ................................................................................ 7 Overview of the Music, Radio and Related Media Industries....................................... 15 Previous Evidence on the Sales Impact of Radio Exposure .......................................... 31 An Econometric Analysis of Radio Airplay and Recording Sales ................................ 38 Summary and Policy Implications................................................................................. 71 Appendix A: Options in Dealing with Measurement Error........................................... 76 Appendix B: Supplemental Regression Results ............................................................ 84 © 2008 National Association of Broadcasters 2 About the Author and Acknowledgements About the Author Dr. James N. Dertouzos has more than 25 years of economic research and consulting experience. Over the course of his career, Dr. Dertouzos has conducted more than 100 major research projects. His Ph.D. is in economics from Stanford University. Dr. Dertouzos has served as a consultant to a wide variety of private and public