House and Home Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hello, My Name Is Igor and I Am a Russian by Birth. I Have Read A

Added 31 Jan 2000 "Hello, My name is Igor and I am a Russian by birth. I have read a lot about Islam, I have Arabic and Chechen friends and I read a lot about the Holy Koran and its teaching. I resent the drunkenness and stupidity of the Russian society and especially the gorrilla soldiers that are fighting against the noble Mujahideen in Chechnya. I would like to become a Muslim and in connection with this I would like to ask you to give me some guidance. Where do I go in Moscow for help in becoming a Muslim. Inshallah I can accomplish this with your help." [Igor, Moscow, Russia, 28 Jan 2000] "May Allah help you brothers. I am from Kuwait. All Kuwaitis are with you. We hope for you to win this war, inshallah very soon. If you want me to do anything for you, please tell me. I really feel ashamed sitting in Kuwait and you brothers are fighting the kuffar (disbelievers). Please tell me if we can come there with you, can we come?" [Brothers R and R, Kuwait, 30 Jan 2000] "Salam my Brave Mujahadeen who are fighting in Chechnya and the ones administrating this web site. Every day I come to this site several time just to catch a glimpse of the beautiful faces whom Allah has embraced shahadah and to get the latest news. I envy you O Mujahadeen, tears run into my eyes every time I hear any news and see any faces on this site. My beloved brothers, Allah has chosen you to reawaken Muslims around the world. -

From Weaklings to Wounded Warriors: the Changing Portrayal of War-Related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in American Cinema

49th Parallel, Vol. 30 (Autumn 2012) ISSN: 1753-5794 (online) Maseda/ Dulin From Weaklings to Wounded Warriors: The Changing Portrayal of War-related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in American Cinema Rebeca Maseda, Ph.D and Patrick L. Dulin, Ph.D* University of Alaska Anchorage “That which doesn’t kill me, can only make me stronger.”1 Nietzche’s manifesto, which promises that painful experiences develop nerves of steel and a formidable character, has not stood the test of time. After decades of research, we now know that traumatic events often lead to debilitating psychiatric symptoms, relationship difficulties, disillusionment and drug abuse, all of which have the potential to become chronic in nature.2 The American public is now quite familiar with the term Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), its characteristics and associated problems. From what we know now, it would have been more appropriate for Nietzche to have stated “That which doesn’t kill me sometimes makes me stronger, sometimes cripples me completely, but regardless, will stay with me until the end of my days.” The effects of trauma have not only been a focus of mental health professionals, they have also captured the imagination of Americans through exposure to cultural artefacts. Traumatized veterans in particular have provided fascinating material for character development in Hollywood movies. In many film representations the returning veteran is violent, unpredictable and dehumanized; a portrayal that has consequences for the way veterans are viewed by U.S. society. Unlike the majority of literature stemming from trauma studies that utilizes Freudian * Dr Maseda works in the Department of Languages at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, and can be reached at [email protected]. -

Noble and Brave Sikh Women

NOBLE & BRAVE SIKH WOMEN Sawan singh NOBLE AND BRAVE SIKH WOMEN (Short biographies of twenty noble and Brave sikh women.) By Sawan Singh Noble and Brave sikh women Sawan Singh Principal (Retd.) 10561,Brier Lane Santa Ana, 92705 CA, USA Email- [email protected] Dedicated to To the Noble and Brave Sikh women who made the sikh nation proud….. Introduction Once I had a chance to address a group of teenage girls, born and educated out of the Punjab, about the sacrifices and achievements of the Sikh women. I explained to them, with examples from the lives of noble and brave Sikh ladies, that those ladies did not lag behind Sikh men in sacrificing their lives for their faith .I narrated to them the bravery of Mai Bhago and social service rendered by Bibi Harnam Kaur. They were surprised to learn about the sacrifices of the Sikh women in the Gurdwara Liberation Movemet. They wanted me to name an English book that should contain short biographies of about twenty such women, but those biographies should be based on history, and not fiction. I could not think of any such book off hand and promised that I would find one. I contacted many friends in India, U.S.A., Canada, and U.K to find such a book, but could not find any. I was told by a friend of mine in Delhi that there was such a book named “Eminent Sikh Women” by Mrs. M.K. Gill, but was out of stock. I was shocked that in our male dominated society Sikh women were not being paid due attention. -

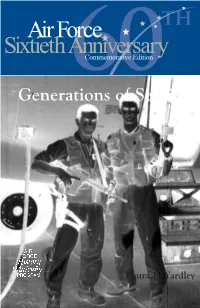

Generations of Service

Generations of Service Laura E. Yardley Generations of Service Laura E. Yardley 2008 COVER PHOTO: CMSgt. Ralph “Bucky” Dent (left) and son TSgt. Jason Dent at an undisclosed location. Foreword If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then certainly any parent, broth- er, sister or cousin, aunt or uncle is honored to see a loved family member follow in his or her footsteps to military service. In old Europe it was traditionally the second son, since only the eldest could inherit the land. But in America the oppor- tunity is there for any fledgling to dream, “I want to serve in the Air Force, just like my Uncle/Brother/ Grandfather Bob.” Few are more aware of the demands of military service than those who serve, so to have a loved one make the com- mitment can be bittersweet—on the one hand a joy and honor; on the other the knowledge that it can be too frequently a tough way to make a living. In this short study you will meet several such families, and you will learn about their relationships and the reasons some have seen a clear path that has been forged by the generations ahead of them. Myriad reasons motivate these multiple generations of Airmen, some of which are clearly expressed, while others are just felt: honor, pride, responsibility, patriotism, courage. The author herself is expe- riencing the family tie of common service: she served as an active duty, now reserve, officer; her husband served as an active duty enlisted man and officer and is now an Air Force civilian. -

Download Solo Acting Script Rtf for Iphone

Solo acting script. Ueda Hankyu Bldg. Office Tower 8-1 Kakuda-cho Kita-ku, Osaka 530-8611, JAPAN ISO9001/ISO14001 Company Our missions please help me with a drama script of 20 mins play about how can creative industries,a vehicle for sustainable development. I'm searching for an effective script for my final project at university. I'm a drama student and I need a long monologue script for female. please help. topic– once i found a lost TEEN he lost his way. is a fantastic place to start. Smith has written several other brilliant one woman shows; another one to check out is 2016's. 6 f, 6 m, 23 either (6-38 actors possible: 3-29 f, 3-29 m). hi, need a script for reader's theater for 6 person and 3- 5mins only, well a script with emotions.. much better if its a drama. Thnks! Additional Resource: Read the ActorPoint featured article on Finding. here. Proper credit is given to authors and writers where applicable. "You're a Mad Man, Charlie Brown" Monologue-Man (12- 15 minutes). 8 f, 8 m, 14 either (16- 85 actors possible: 8-62 f, 8-54 m). Ten Great Plays for Actors in their Twenties. 5 f, 3 m, 12 either (5-18 actors possible: 5-17 f, 3-15 m). Ask your TEENdos. get the material from them and record it all. They'll relate if the words came out of their mouths. You just finesse the flow. Easier said than done, but using 'my' TEENs' ideas, words and thoughts have worked really well for me. -

Beacherjun28.Pdf

TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 17, Number 25 Thursday, June 28, 2001 Page 1 June 28, 2001 911 Franklin Street • Michigan City, IN 46360 219/879-0088 • FAX 219/879-8070 In Case Of Emergency, Dial e-mail: News/Articles - [email protected] email: Classifieds - [email protected] http://www.bbpnet.com/Beacher/ Published and Printed by THE BEACHER BUSINESS PRINTERS Delivered weekly, free of charge to Birch Tree Farms, Duneland Beach, Grand Beach, Hidden 911 Shores, Long Beach, Michiana Shores, Michiana MI and Shoreland Hills. The Beacher is also Subscription Rates delivered to public places in Michigan City, New Buffalo, LaPorte and Sheridan Beach. 1 year $26 6 months $14 3 months $8 1 month $3 Have a Heart For John Hart This Fourth of July by Charles McKelvy “First prize: one week in Philadelphia. Second prize: two weeks in Philadelphia.” —W.C. Fields My parents are from Philadelphia, and many of my duty every Fourth of July for the last 51 years with relatives still live there, so I know how hot and the “shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and muggy it can be there on the 4th of July and the rest illuminations” bit. of the summer. But I’ve been more than a little remiss on the In fact, I once had the dubious duty of serving two solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty part. At least weeks of active duty as a Naval Reservist at the until last year when I read an article in a national mag- Philadelphia Naval Yard during a particularly hot and azine about the suffering that nearly all of the 55 sign- wet Philly summer. -

The District and Province of America (Part I): Our American Schools (1885-1911)

MARIST BROTHERS OF THE PROVINCE OF CANADA Archival Bulletin FMS - Volume 3. # 6 (July 2013) The DisTricT anD Province of america (ParT i): our american schools (1885-1911) 1st Row : Brother Félix-Eugène (Provincial 1903-1905), Brother Césidius (1885-1903 Founder), Brother Angélicus (Provincial 1905-1907), A.G, Brother Zéphiriny (Provincial 1907-1909). 2nd Row : Brother Légontianus, Brother Héribert, Brother Ptoméléus (Provincial 1909-1911) and Brother Gabriel-Marie. Circa 1927 1 St. Pierre School: Lewiston (Maine) - Founded 1886 School, always school, nothing but school. This is a characteristic slogan of educational work in New England. The national parishes have always had to support their schools and have done so in a remarkable way, by teaching and supporting the young. Here is briefly, the history of education at St. Peter's Parish of Lewiston. In 1870-71, with the founding of the parish, Miss. Lacourse had the honor of giving young Franco-Americans the first rudiments of knowledge. She taught the students in her own home. After leaving for Canada in 1873, two other young ladies, Miss. Vidal and Bourbeau, took charge of the sixty pupils who wished to learn. The parish priest Hévey brought the Sisters of Saint-Hyacinthe to Lewiston in 1878, to provide education to the students in an institutional setting. Their first classes were at their little orphanage, Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes. The Sisters taught until 1892. 2 Taking charge of the parish, the Dominicans quickly built the first great school, known as the Dominican Block. It took the name of St. Pierre in 1883. It was at the urgent request of Father Mothon, O.P. -

Household Papers and Stories, by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Project Gutenberg's Household Papers and Stories, by Harriet Beecher Stowe This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Household Papers and Stories Author: Harriet Beecher Stowe Release Date: February 8, 2010 [EBook #31217] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOUSEHOLD PAPERS AND STORIES *** Produced by David Edwards, Katherine Ward, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.) THE WRITINGS OF HARRIET BEECHER STOWE Riverside Edition WITH BIOGRAPHICAL INTRODUCTIONS PORTRAITS, AND OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS IN SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME VIII HOUGHTON MIFFLIN & CO HOUSEHOLD PAPERS AND STORIES BY HARRIET BEECHER STOWE BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY The Riverside Press, Cambridge 1896 Copyright, 1868, BY TICKNOR & FIELDS. Copyright, 1864, 1892, 1896, BY HARRIET BEECHER STOWE. Copyright, 1896, BY HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO. All rights reserved. The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A. Electrotyped and Printed by H. O. Houghton & Co. CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTORY NOTE vii HOUSE AND HOME PAPERS I. THE RAVAGES OF A CARPET 1 II. HOMEKEEPING VS. HOUSEKEEPING 16 III. WHAT IS A HOME? 33 IV. THE ECONOMY OF THE BEAUTIFUL 54 V. RAKING UP THE FIRE 69 VI. THE LADY WHO DOES HER OWN WORK 85 VII. WHAT CAN BE GOT IN AMERICA 101 VIII. ECONOMY 112 IX. -

Perseus the Brave

1 P E R S E U S T H E B R A V E A play in Seven Scenes for the Fifth Grade by Roberto Trostli The Hartsbrook School 193 Bay Road Hadley, MA 01035 (413) 586-1908 [email protected] 2 Author’s note: This play is one of a group of plays written for the classes I taught at the Rudolf Steiner School in New York from 1982–1991 and at The Hartsbrook School in Hadley, MA from 1991-1999. The theme of each play was chosen to address a particular class’s issues and interests, and the characters were rendered with specific students in mind. When other teachers and classes have performed my plays, I have encouraged them to adapt or revise the play as necessary to derive the maximum pedagogical value from it. Other class’s performances have showed me artistic dimensions of my plays that I could not have imagined, and I have always been grateful to see that my work has taken on new life. I have posted my plays on the Online Waldorf Library as Microsoft Word documents so that they can easily be downloaded and changed. I have purposely given few stage directions so that teachers and students will make the plays more their own. Dear Colleagues: I hope that these plays will serve you well as inspiration, as a scaffold on which to build your own creation, or as a script to make your own. Please don’t hesitate to take whatever liberties you wish so that the play may serve you in your work.