Transit-Oriented Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Diversity and Affordability in New

HOUSING DIVERSITY AND AFFORDABILITY IN NEW JERSEY’S TRANSIT VILLAGES By Dorothy Morallos Mabel Smith Honors Thesis Douglass College Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey April 11, 2006 Written under the direction of Professor Jan S. Wells Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy ABSTRACT New Jersey’s Transit Village Initiative is a major policy initiative, administered by the New Jersey Department of Transportation that promotes the concept of transit oriented development (TOD) by revitalizing communities and promoting residential and commercial growth around transit centers. Several studies have been done on TODs, but little research has been conducted on the effects it has on housing diversity and affordability within transit areas. This research will therefore evaluate the affordable housing situation in relation to TODs in within a statewide context through the New Jersey Transit Village Initiative. Data on the affordable housing stock of 16 New Jersey Transit Villages were gathered for this research. Using Geographic Information Systems Software (GIS), the locations of these affordable housing sites were mapped and plotted over existing pedestrian shed maps of each Transit Village. Evaluations of each designated Transit Village’s efforts to encourage or incorporate inclusionary housing were based on the location and availability of affordable developments, as well as the demographic character of each participating municipality. Overall, findings showed that affordable housing remains low amongst all the designated villages. However, new rules set forth by the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH) may soon change these results and the overall affordable housing stock within the whole state. -

Community Open House #1 South Gate Park January 27, 2016 Today’S Agenda

Community Open House #1 South Gate Park January 27, 2016 Today’s Agenda 1) Gateway District Specific Plan 2) Efforts To Date 3) Specific Plan Process 4) TOD Best Practices 5) Community Feedback 27 JANUARY 2016 | page 2 Gateway District Specific Plan What is the West Santa Ana Branch? The West Santa Ana Branch (WSAB) is a transit corridor connecting southeast Los Angeles County (including South Gate) to Downtown Los Angeles via the abandoned Pacific Electric Right- of-Way (ROW). Goals for the Corridor: 1. PLACE-MAKING: Make the station the center of a new destination that is special and unique to each community. 2. CONNECTIONS: Connect residential neighborhoods, employment centers, and destinations to the station. 3. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT TOOL: Concentrate jobs and homes in the station area to reap the benefits that transit brings to communities. 27 JANUARY 2016 | page 4 What is light rail transit? The South Gate Transit Station will be served by light rail and bus services. Light Rail Transit (LRT) is a form of urban rail public transportation that operates at a higher capacity and higher speed compared to buses or street-running tram systems (i.e. trolleys or streetcars). LRT Benefits: • LRT is a quiet, electric system that is environmentally-friendly. • Using LRT helps reduce automobile dependence, traffic congestion, and Example of an at-grade alignment LRT, Gold Line in Pasadena, CA. pollution. • LRT is affordable and a less costly option than the automobile (where costs include parking, insurance, gasoline, maintenance, tickets, etc..). • LRT is an efficient and convenient way to get to and from destinations. -

Academic Perspectives on Minimum Parking: Congestion Typical Commerical Lot 7,500 Sq

setting the stage: parking policy as Los Angeles matures and the regional transit system is built Regional Context Regional Context Robin Blair (METRO) Robin Blair is something that is essential to the FTA funding Jay Kim (LADOT) Jay Kim is the security, liability, and insurance issues, there a Planning Director at Metro and the process and to the criteria we are using. So Acting Assistant General Manager could be maximum flexibility in dealing with Parking Policy Modal Lead for the far, the city of Los Angeles and the surround- for the newly re-organized Office of parking.” 2011 Call for Projects. Parking Management, Planning and ing cities have adopted fairly aggressive land Regulations with the Department of use policies which favor transit use.” Transportation. He has over 20 years of transportation planning and engi- neering experience from both private • “Currently the renaissance of rail raises and public sectors. the issue of land use, which is the most considered factor for the Federal Trans- • “Because we impose parking require- portation Agency (FTA) in evaluating any The five criteria of FTA’s ments on a project-by-project basis and In the U.S. we have built new funding. In this context, the discus- evaluation for fund- parking spaces are not designed to be three spaces per each sion of parking around transit becomes “ publically shared, we over-provide park- “ important.” ing are the existing land ing. Parking spaces should be shared.” car. In downtown in par- • “Places like MacArthur Park have well use, the containment of • Regarding shared parking, “every build- ticular, we have dedi- survived and people gravitated to these ing will probably need to have some por- areas where they could get around the sprawl, transit supporting tion of the parking dedicated for their use; cated 81% of the land for city without using automobiles. -

Transit Service Plan

Attachment A 1 Core Network Key spines in the network Highest investment in customer and operations infrastructure 53% of today’s bus riders use one of these top 25 corridors 2 81% of Metro’s bus riders use a Tier 1 or 2 Convenience corridor Network Completes the spontaneous-use network Focuses on network continuity High investment in customer and operations infrastructure 28% of today’s bus riders use one of the 19 Tier 2 corridors 3 Connectivity Network Completes the frequent network Moderate investment in customer and operations infrastructure 4 Community Network Focuses on community travel in areas with lower demand; also includes Expresses Minimal investment in customer and operations infrastructure 5 Full Network The full network complements Muni lines, Metro Rail, & Metrolink services 6 Attachment A NextGen Transit First Service Change Proposals by Line Existing Weekday Frequency Proposed Weekday Frequency Existing Saturday Frequency Proposed Saturday Frequency Existing Sunday Frequency Proposed Sunday Frequency Service Change ProposalLine AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl R2New Line 2: Merge Lines 2 and 302 on Sunset Bl with Line 200 (Alvarado/Hoover): 15 15 15 20 30 60 7.5 12 7.5 15 30 60 12 15 15 20 30 60 12 12 12 15 30 60 20 20 20 30 30 60 12 12 12 15 30 60 •E Ğǁ >ŝŶĞϮǁ ŽƵůĚĨŽůůŽǁ ĞdžŝƐƟŶŐ>ŝŶĞƐϮΘϯϬϮƌŽƵƚĞƐŽŶ^ƵŶƐĞƚůďĞƚǁ -

1 Document Overview.Cdr

Section 2. CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND ! Local & Regional Setting ! Historical Context ! Physical Context: Land Use ! Physical Context: Mobility ! Physical Context: Urban Design ! Socio-economic Context ! Policy Context ! Community Values Section 2 CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND 11 Local & Regional Setting Regional Setting Pasadena is situated at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains in the western San Gabriel Valley, approximately 10 miles northeast of downtown Los Angeles. This location offers numerous advantages, including convenient freeway and airport access that will continue to provide the City a competitive advantage as a regional business hub. Moreover, few localities can match the physical beauty afforded by the backdrop of the San Gabriels. San Gabriel Mountains Local Setting Located in the heart of the City, the Central District’s approximately 960 acres essentially correspond to the area recognized by Pasadena’s residents as “Downtown.” (Downtown and Central District will be used interchangeably in this document.) Included within its boundaries are the activity centers popularly known as Old Pasadena, the Civic Center, the Playhouse District, and South Lake Avenue; each makes a special contribution to this urban setting with an active mixture of uses. The Central District’s boundaries are clearly marked to the north and west by the 210 and 710 Freeways respectively, and it’s buildings are prominent features along these highways. Approaching the campuses of the California Institute of California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and Pasadena City College (PCC), the eastern Technology boundary lies one to two blocks east of Lake Avenue. The southern limit roughly follows California Boulevard, except that the Specific Plan area includes the Arroyo Parkway corridor extending from the 110 Freeway into the midst of Downtown. -

Metro Public Hearing Pamphlet

Proposed Service Changes Metro will hold a series of six virtual on proposed major service changes to public hearings beginning Wednesday, Metro’s bus service. Approved changes August 19 through Thursday, August 27, will become effective December 2020 2020 to receive community input or later. How to Participate By Phone: Other Ways to Comment: Members of the public can call Comments sent via U.S Mail should be addressed to: 877.422.8614 Metro Service Planning & Development and enter the corresponding extension to listen Attn: NextGen Bus Plan Proposed to the proceedings or to submit comments by phone in their preferred language (from the time Service Changes each hearing starts until it concludes). Audio and 1 Gateway Plaza, 99-7-1 comment lines with live translations in Mandarin, Los Angeles, CA 90012-2932 Spanish, and Russian will be available as listed. Callers to the comment line will be able to listen Comments must be postmarked by midnight, to the proceedings while they wait for their turn Thursday, August 27, 2020. Only comments to submit comments via phone. Audio lines received via the comment links in the agendas are available to listen to the hearings without will be read during each hearing. being called on to provide live public comment Comments via e-mail should be addressed to: via phone. [email protected] Online: Attn: “NextGen Bus Plan Submit your comments online via the Public Proposed Service Changes” Hearing Agendas. Agendas will be posted at metro.net/about/board/agenda Facsimiles should be addressed as above and sent to: at least 72 hours in advance of each hearing. -

The Zoning and Real Estate Implications of Transit-Oriented Development

TCRP Transit Cooperative Research Program Sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration LEGAL RESEARCH DIGEST January 1999--Number 12 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Subject Areas: IA Planning and Administration, IC Transportation Law, VI Public Transit, and VII Rail The Zoning and Real Estate Implications of Transit-Oriented Development This report was prepared under TCRP Project J-5, "Legal Aspects of Transit and Intermodal Transportation Programs, "for which the Transportation Research Board is the agency coordinating the research. The report was prepared by S. Mark White. James B. McDaniel, TRB Counsel for Legal Research Projects, was the principal investigator and content editor. THE PROBLEM AND ITS SOLUTION transit-equipment and operations guidelines, FTA financing initiatives, private-sector programs, and The nation's transit agencies need to have access labor or environmental standards relating to transit to a program that can provide authoritatively operations. Emphasis is placed on research of current researched, specific, limited-scope studies of legal importance and applicability to transit and intermodal issues and problems having national significance and operations and programs. application to their businesses. The TCRP Project J-5 is designed to provide insight into the operating APPLICATIONS practices and legal elements of specific problems in transportation agencies. Local government officials, including attorneys, The intermodal approach to surface planners, and urban design professionals, are seeking transportation requires a partnership between transit new approaches to land use and development that and other transportation modes. To make the will address environmental impacts of increased partnership work well, attorneys for each mode need automobile traffic and loss of open space around to be familiar with the legal framework and processes cities and towns, and alleviate financial pressures on of the other modes. -

Transit Village Symposium: “Progress and Future”

‘ Progress and Future’ 2nd Transit Village Symposium Summary of Proceedings sponsored by: Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy and New Jersey Department of Transportation with support from The New Jersey State League of Municipalities September 2006 “Progress and Future” — 2nd Transit Village Symposium, June 9, 2006 Executive Summary n Friday, June 9, 2006, more than 150 invited leaders from the public sector, private industry and O non-governmental organizations gathered in New Brunswick to take stock in New Jersey’s effort to support the Transit Village Initiative, which facilitates targeted development and redevelopment near transit stations, a strategy known as transit-oriented development (TOD). The impetus for this gathering was, in part, the change in leadership in state government — now headed by Governor Jon Corzine. S ponsored by the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT), the symposium was organized by the Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center of the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Additional support was provided by the New Jersey State League of Municipalities. T he New Jersey Transit Village Initiative seeks to revitalize and grow selected communities with transit as an anchor. A Transit Village is designated as the half-mile area around a transit facility (this is also typically referred to as a TOD district). There are currently 17 designated Villages: Belmar, Bloomfield, Bound Brook, Collingswood, Cranford, Jersey City, Matawan, Metuchen, Morristown, New Brunswick, Netcong, Pleasantville, Rahway, Riverside, Rutherford, South Amboy, and South Orange. In opening remarks, Dean James W. -

Gold Line Allen Station Connections

Allen Connections metro.net Destinations Lines Stops IYWb[DcZJc^i/&$'B^aZ JJ;CFB;7BO;CFB; 7BO C;HH;JJIJC;HH;JJ IJ ;L;BODFB;L;BOD FB BEC7L?IJ7IJBEC7 L?IJ7 IJ Alhambra 485 B BEC7L?IJ7IJ Altadena 180, 485, 686 AJ 8EOBIJEDIJ D;BIED7BO L L L MH?=>J7L Av 64 256 K 7 7 ; BC F7BEC7IJ ? H 7L Azusa FT690 B 7 I Cal State LA Station Å 485 B J :KD>7C7BO California Bl 177, ARTS 20 BK Cal Tech 485, ARTS 10, 20 BGHL EH7D=;=HEL;8B EH7D=;=HEL;8B Å B Claremont TransCenter FT690 9H7M<EH:7BO Colorado Bl 180, 256, 686, ARTS 10 BGH ;7HB>7CIJ ; E B7IBKD7IIJ KL : D 8 H ? 7 E BGH ; Del Mar Station 177, 686, ARTS 20 B 9B?<JED7BOED 7BO 7 E 7 L A E D KL B H I7DJ787H87H7IJ 7 CEDJ;L?IJ7IJL?IJ7 IJ ; C 7 E L H B >?BB7 B >EBB?IJED Downtown Los Angeles 485 B Je=ersonsonn ; D D;MJED7BO >7C?BJED7L B B ? ? B7A;7L C?9>?=7D7L 7 9>;IJ;H7L C;DJEH7L M?BIED7L 97J7B?D77L C7HL?IJ77L 9B7HA7BO Park 887B:M?D7BO7B:M?D 7BO I?;HH78ED?J77L I I I?D7BE77L ; ;BCEB?DE7L 7 Eastern Av 256 K ; 7BB;D7L C F7BEL;H:;7L F El Sereno 256 K L?BB7IJ L?BB7IJIJ O Villa Gardens Kaiser B Encino CE549 B 7 Retirement Clinic JOB;H7BO : I Fremont Av 485 B Commmunity < M7=D;HIJM7=D;H IJ J = J >K:IED7L ; Glendale via 134 Fwy CE549 B 8;JJI7BO 8 K C7FB;MO Lake Avenue Church C7FB;IJ; IJ Highland Park 256 87HJB;JJ7BO 7bb[dIjWj_ed G C[ceh_WbFWhaIjWj_ed C7FB;IJ JPL 177 <MO '&% 7 BWa[IjWj_ed <EEJ>?BB LA County+USC 485 B IJJ 9EHIEDD L Medical Center Station @ 7 8 A 7 I L L 9EHIEDIJ > E La Verne FT690 B 7 H 7 B 7L O 7 B A L 7 BEGH BE9KIJIJIJ : 7 Memorial Park Station 180, 686, ARTS 10, 40 L J 9 7 BE9KIJIJ D D E7A -

University of California Transportation Center UCTC-FR-2012-05

University of California Transportation Center UCTC-FR-2012-05 A New-found Popularity for Transit-oriented Developments? Lessons from Southern California Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, University of California, Los Angeles April 2012 This article was downloaded by: [University of California, Los Angeles] On: 25 June 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 918974530] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Urban Design Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713436528 A New-found Popularity for Transit-oriented Developments? Lessons from Southern California Anastasia Loukaitou-Siderisa a Department of Urban Planning, University of California, Los Angeles, USA Online publication date: 18 January 2010 To cite this Article Loukaitou-Sideris, Anastasia(2010) 'A New-found Popularity for Transit-oriented Developments? Lessons from Southern California', Journal of Urban Design, 15: 1, 49 — 68 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/13574800903429399 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13574800903429399 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. -

Morristown Plan Endorsement Process

TOWN OF MORRISTOWN MUNICIPAL SELF-ASSESSMENT REPORT Town of Morristown Plan Endorsement Process Prepared by: Town of Morristown Planning Division Topology NJ, LLC April 2020 Page 1 of 63 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Section 4 Introduction 5 Location and Regional Context 6 Demographics 9 Community Inventory 16 Community Vision & Public Participation 18 Status of Master Plan and Other Relevant Planning Activities 20 Recent and Upcoming Development Activities 22 Statement of Planning Coordination 23 State Programs, Grants and Capital Projects 24 Internal Consistency in Local Planning 25 Sustainability Statement 26 Consistency with State Plan – Goals, Policies and Indicators 34 Consistency with State Plan – Center Criteria and Policies 36 Consistency with State Plan – Planning Area Policy Objectives 38 State Agency Assistance 39 Conclusion 40 Appendix A: List of Maps 51 Appendix B: Contaminated Sites in Morristown 54 Appendix C: Overview of Zoning Board of Adjustment Applications Page 2 of 63 [THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] Page 3 of 63 INTRODUCTION New Jersey’s State Development & Redevelopment Plan (State Plan), adopted in 1992 and readopted in 2001, articulates the State’s long-term goals, policies, and objectives. It guides policy making at and coordination between all levels of government for housing, economic development, land use, transportation, natural resource conservation, agriculture and farmland retention, historic preservation, and public facilities and services. The State Plan allows the State Planning Commission to designate several types of Centers. These designations promote dense growth to combat sprawl, increase housing inventories, promote economic development, and enhance the overall quality of life. Morristown currently is designated as a Regional Center. -

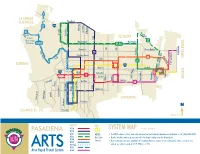

System Map Effective July 2013 • for Arts Schedule, Fare, and Route Information Visit Or Call (626) 398-8973

Pasadena SyStem map effective July 2013 • For aRtS schedule, fare, and route information visit www.cityofpasadena.net/artsbus or call (626) 398-8973. • Route schedules and maps are available for downloading from the City website. • Route schedules are also available at pasadena libraries, major hotels, community centers, on our buses, arts and at our office located at 221 e. Walnut, #199. area Rapid transit System paSadeNa aRea Rapid tRaNSit SyStem map rouTe no. direcTion Frequency GeneraL hourS oF operaTion* (refer to schedules for specific times) 10 east & West 25 minutes mon-Fri 6am to 8pm; Sat 11am to 8pm 20 Clockwise mon-Fri: about 20-25 min. (average) mon-Fri 6am to 8pm; Sat 11am to 8pm Sat: 35 minutes 20 Counterclockwise mon-Fri: about 20-25 min. (average) mon-Fri 6am to 8pm; Sat 11am to 8pm Sat: 35 minutes 31 east once an hour mon-Fri 6am to 8pm; Sat 11am to 8pm mon - Fri Rush Hrs: am - 15-30 minutes; pm - 2 trips 31 West once an hour mon-Fri 6am to 8pm; Sat 11am to 8pm Rush Hrs: am - 2 trips; pm - 15-35 minutes 32 east 70 minutes mon-Fri 6am to 8pm; Sat 11am to 8pm mon - Fri Rush Hrs: am - 60-70 minutes; pm - 15-30 minutes arTS ScheduLe/rouTe inForMaTion 32 West 70 minutes mon-Fri 6am to 8pm; Sat 11am to 8pm (626) 398-8973 Rush Hrs: am - 15-35 minutes; pm - 70 minutes adMiniSTraTive oFFice 40 east & West 30 minutes mon-Fri 6am to 7:30pm; Sat 11am to 8pm mon-Fri Rush Hrs: 15-30 minutes tRaNSit diviSioN department of transportation 51 North & South once an hour (to/from art Center) mon-Fri 6am to 8pm: weekday service only City of pasadena 51 SatuRday North & South 22 minutes (memorial park/Rose bowl) Sat 7:30am to 8pm: Saturday only 221 east Walnut Street, Suite 199 SeRviCe pasadena, Ca 91101 52 mon-Fri (626) 744-4055 1 trip in the morning and 2 trips in the afternoon www.cityofpasadena.net/artsbus 60 east & West 45-50 minutes mon-Fri 6am to 10:30am & 2:45pm to 7:25pm peak hour weekday service only *Holidays: aRtS buses do not operate on New years day, memorial day, Fourth of July, Labor day, thanksgiving day, Christmas day.