Problems in Devonian Stratigraphy, Northeastern Alberta Chris L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Petroleum Virgo Technical Update NORTHERN PETROLEUM PLC

Northern Petroleum Virgo Technical Update NORTHERN PETROLEUM PLC 23rd October 2014 Disclaimer These presentation materials (the "Presentation Materials") are being solely issued to and directed at persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments and who are investment professionals as specified in Article 19(5) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005 (the "Financial Promotions Order") or to persons who are high net worth companies, unincorporated associations or high value trusts as specified in Article 49(2) of the Financial Promotions Order (“Exempt Persons”). The Presentation Materials are exempt from the general restriction on the communication of invitations or inducements to enter into investment activity on the basis that they are only being made to Exempt Persons and have therefore not been approved by an authorised person as would otherwise be required by section 21 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”). Any investment to which this document relates is available to (and any investment activity to which it relates will be engaged with) Exempt Persons. In consideration of receipt of the Presentation Materials each recipient warrants and represents that he or it is an Exempt Person. The Presentation Materials do not constitute or form any part of any offer or invitation to sell or issue or purchase or subscribe for any shares in Northern Petroleum PLC (“Northern Petroleum”) nor shall they or any part of them, or the fact of their distribution, form the basis of, or be relied on in connection with, any contract with Northern Petroleum relating to any securities. -

Characterization of Geothermal Reservoir Units in Northwestern

PROCEEDINGS, Thirty-Eighth Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering Stanford University, Stanford, California, February 11-13, 2013 SGP-TR-198 CHARACTERIZATION OF GEOTHERMAL RESERVOIR UNITS IN NORTHWESTERN ALBERTA BY 3D STRUCTURAL GEOLOGICAL MODELLING AND ROCK PROPERTY MAPPING BASED ON 2D SEISMIC AND WELL DATA Simon N. Weides1, Inga S. Moeck2, Douglas R. Schmitt2, Jacek A. Majorowicz2, Elahe P. Ardakani2 1 Helmholtz Centre Potsdam GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 2 University of Alberta, 11322-89 Ave., Edmonton, AB, Canada e-mail: [email protected] the south-western part of the study area its temperature ABSTRACT is above 70 °C and the effective porosity is estimated with 10 % to 15 %. Foreland basins such as the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) host a variety of geoenergy Geothermal heat could play a role as energy source for resources. Often, the focus is on hydrocarbon resources district heating. In energy intensive in-situ oil sands but in times of discussions about climate change and extraction processes geothermal heat could be used for environmental aspects, additional green energy preheating of water for steam production. This would resources are under examination. This study explores lower the amount of natural gas used in oil sands Paleozoic formations in the north western WCSB with production and reduce climate gas emissions. regard to their usability as geothermal reservoirs. The study focuses on an area around Peace River in north – western Alberta. This research site covers an area of INTRODUCTION approx. 90 km * 70 km with a basin depth of 1.7 km to 2.4 km. -

Helium in Northeastern British Columbia

HELIUM IN NORTHEASTERN BRITISH COLUMBIA Elizabeth G. Johnson1 ABSTRACT Global demand for helium is increasing at a time when world reserves are in decline. The price of grade A helium has quadrupled in the past 12 years. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) processing can be used to capture helium as a value-added byproduct at concentrations as low as 0.04% by volume. The Slave Point, Jean Marie (Redknife) and Wabamun formations of northeastern British Columbia preferentially have helium associated with many of their natural gas pools. The mechanism for this accumulation appears to be flow in hydrothermal brines from helium-enriched basement granitic rocks along deeply seated faults. Separately, the Evie member of the Horn River Formation also has anomalous helium accumulation in its shale gas related to uranium decay in organic-rich shales. Johnson, E.G. (2012): Helium in northeastern British Columbia; in Geoscience Reports 2013, British Columbia Ministry of Natural Gas Development, pages 45–52. 1Geoscience and Strategic Initiatives Branch, British Columbia Ministry of Natural Gas Development, Victoria, British Columbia; [email protected] Key Words: Helium, LNG, Jean Marie, Slave Point, Wabamun, Evie, Horn River Formation INTRODUCTION optical fibre technology (8% of global use; Peterson and Madrid, 2012; Anonymous, 2012). Helium is a nonrenewable resource that has developed In recognition of its strategic value, the United States important strategic value. Helium (atomic number of 2) ex- 4 created the Federal Helium Reserve in the Bush Dome Res- ists primarily as the stable isotope, He, which is produced ervoir, Texas, in 1925. The primary source for the Federal on the earth through alpha decay of radioactive elements Helium Reserve is the world-class Hugoton Reservoir in such as uranium and thorium. -

CO2 Storage in a Devonian Carbonate System, Fort Nelson British Columbia

CO2 Storage in a Devonian Carbonate System, Fort Nelson British Columbia by Peter W. Crockford BSc., University of Victoria, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences Peter W. Crockford 2011 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-88283-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-88283-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. -

An Investigation of the Interrelationships Among

AN INVESTIGATION OF THE INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG STREAMFLOW, LAKE LEVELS, CLIMATE AND LAND USE, WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE BATTLE RIVER BASIN, ALBERTA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science in the Department of Civil Engineering by Ross Herrington Saskatoon, Saskatchewan c 1980. R. Herrington ii The author has agreed that the Library, University of Ssskatchewan, may make this thesis freely available for inspection. Moreover, the author has agreed that permission be granted by the professor or professors who supervised the thesis work recorded herein or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which the thesis work was done. It is understood that due recognition will be given to the author of this thesis and to the University of Saskatchewan in any use of the material in this thesiso Copying or publication or any other use of the thesis for financial gain without approval by the University of Saskatchewan and the author's written permission is prohibited. Requests for permission to copy or to make any other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Civil Engineering Uni ve:rsi ty of Saskatchewan SASKATOON, Canada. iii ABSTRACT Streamflow records exist for the Battle River near Ponoka, Alberta from 1913 to 1931 and from 1966 to the present. Analysis of these two periods has indicated that streamflow in the month of April has remained constant while mean flows in the other months have significantly decreased in the more recent period. -

Keg River Oil and Gas Assessment Unit 52430102

Keg River Oil and Gas Assessment Unit 52430102 135 130 125 120 115 65 # # 60 # ## ###### 5243 ############ ############ ###### # ########### # 5245 # ############ ## ######### # # ## # ## 55 Edmonton ÚÊ ÚÊ Calgary 50 Canada United States 0 250 500 KILOMETERS Keg River Oil and Gas Assessment Unit 52430102 Alberta Basin Geologic Province 5243 Other geologic province boundary USGS PROVINCES: Alberta Basin and Rocky Mountain Deformed Belt (5243 and 5245) GEOLOGIST: M.E. Henry TOTAL PETROLEUM SYSTEM: Keg River-Keg River (524301) ASSESSMENT UNIT: Keg River Oil and Gas (52430102) DESCRIPTION: This oil and gas assessment unit includes the northwestern part of the Alberta Basin and a small part of the east-central deformed belt. The area is generally bounded by the Tathlina High to the north and the Peace River Arch to the south. The eastern boundary is the estimated extent of potential reservoir rocks and the western boundary is the Keg River Gas assessment unit. SOURCE ROCKS: The principal source rocks are organic-rich, fine-grained rocks of the Middle Devonian Keg River Formation. MATURATION: The western half of this unit lies in the area where probable source rocks are expected to be mature with respect to liquid petroleum generation. MIGRATION: The distribution of oil and gas pools assigned to this unit in relation to the estimated distribution of mature source rocks indicates that long distance lateral migration is not required. RESERVOIR ROCKS: Virtually all reservoirs occur in dolomite, the majority of which developed in pinnacle reefs and many in patch reefs. TRAPS AND SEALS: The most common trap types are stratigraphic followed by structural and combination in the approximate proportion of 20 to five to one respectively. -

Environmentally Significant Areas of Alberta Volumes 1, 2 and 3

Environmentally Significant Areas of Alberta Volumes 1, 2 and 3 Prepared by: Sweetgrass Consultants Ltd. Calgary, AB for: Resource Data Division Alberta Environmental Protection Edmonton, Alberta March 1997 Environmentally Significant Areas of Alberta Volume 1 Prepared by: Sweetgrass Consultants Ltd. Calgary, AB for: Resource Data Division Alberta Environmental Protection Edmonton, Alberta March 1997 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large portions of native habitats have been converted to other uses. Surface mining, oil and gas exploration, forestry, agricultural, industrial and urban developments will continue to put pressure on the native species and habitats. Clearing and fragmentation of natural habitats has been cited as a major area of concern with respect to management of natural systems. While there has been much attention to managing and protecting endangered species, a consensus is emerging that only a more broad-based ecosystem and landscape approach to preserving biological diversity will prevent species from becoming endangered in the first place. Environmentally Significant Areas (ESAs) are important, useful and often sensitive features of the landscape. As an integral component of sustainable development strategies, they provide long-term benefits to our society by maintaining ecological processes and by providing useful products. The identification and management of ESAs is a valuable addition to the traditional socio-economic factors which have largely determined land use planning in the past. The first ESA study done in Alberta was in 1983 for the Calgary Regional Planning Commission region. Numerous ESA studies were subsequently conducted through the late 1980s and early 1990s. ESA studies of the Parkland, Grassland, Canadian Shield, Foothills and Boreal Forest Natural Regions are now all completed while the Rocky Mountain Natural Region has been only partially completed. -

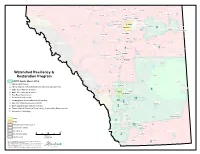

Watershed Resiliency and Restoration Program Maps

VU32 VU33 VU44 VU36 V28A 947 U Muriel Lake UV 63 Westlock County VU M.D. of Bonnyville No. 87 18 U18 Westlock VU Smoky Lake County 28 M.D. of Greenview No. 16 VU40 V VU Woodlands County Whitecourt County of Barrhead No. 11 Thorhild County Smoky Lake Barrhead 32 St. Paul VU County of St. Paul No. 19 Frog Lake VU18 VU2 Redwater Elk Point Mayerthorpe Legal Grande Cache VU36 U38 VU43 V Bon Accord 28A Lac Ste. Anne County Sturgeon County UV 28 Gibbons Bruderheim VU22 Morinville VU Lamont County Edson Riv Eds er on R Lamont iver County of Two Hills No. 21 37 U15 I.D. No. 25 Willmore Wilderness Lac Ste. Anne VU V VU15 VU45 r Onoway e iv 28A S R UV 45 U m V n o o Chip Lake e k g Elk Island National Park of Canada y r R tu i S v e Mundare r r e Edson 22 St. Albert 41 v VU i U31 Spruce Grove VU R V Elk Island National Park of Canada 16A d Wabamun Lake 16A 16A 16A UV o VV 216 e UU UV VU L 17 c Parkland County Stony Plain Vegreville VU M VU14 Yellowhead County Edmonton Beaverhill Lake Strathcona County County of Vermilion River VU60 9 16 Vermilion VU Hinton County of Minburn No. 27 VU47 Tofield E r i Devon Beaumont Lloydminster t h 19 21 VU R VU i r v 16 e e U V r v i R y Calmar k o Leduc Beaver County m S Leduc County Drayton Valley VU40 VU39 R o c k y 17 Brazeau County U R V i Viking v e 2A r VU 40 VU Millet VU26 Pigeon Lake Camrose 13A 13 UV M U13 VU i V e 13A tt V e Elk River U R County of Wetaskiwin No. -

This Work Is Licensed Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. THE TIGER BEETLES OF ALBERTA (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE, CICINDELINI)' Gerald J. Hilchie Department of Entomology University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E3. Quaestiones Entomologicae 21:319-347 1985 ABSTRACT In Alberta there are 19 species of tiger beetles {Cicindela). These are found in a wide variety of habitats from sand dunes and riverbanks to construction sites. Each species has a unique distribution resulting from complex interactions of adult site selection, life history, competition, predation and historical factors. Post-pleistocene dispersal of tiger beetles into Alberta came predominantly from the south with a few species entering Alberta from the north and west. INTRODUCTION Wallis (1961) recognized 26 species of Cicindela in Canada, of which 19 occur in Alberta. Most species of tiger beetle in North America are polytypic but, in Alberta most are represented by a single subspecies. Two species are represented each by two subspecies and two others hybridize and might better be described as a single species with distinct subspecies. When a single subspecies is present in the province morphs normally attributed to other subspecies may also be present, in which case the most common morph (over 80% of a population) is used for subspecies designation. Tiger beetles have always been popular with collectors. Bright colours and quick flight make these beetles a sporting and delightful challenge to collect. -

Subsurface Characterization of the Pembina-Wabamun Acid-Gas Injection Area

ERCB/AGS Special Report 093 Subsurface Characterization of the Pembina-Wabamun Acid-Gas Injection Area Subsurface Characterization of the Pembina-Wabamun Acid-Gas Injection Area Stefan Bachu Maja Buschkuehle Kristine Haug Karsten Michael Alberta Geological Survey Alberta Energy and Utilities Board ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Alberta, 2008 ISBN 978-0-7785-6950-3 The Energy Resources Conservation Board/Alberta Geological Survey (ERCB/AGS) and its employees and contractors make no warranty, guarantee or representation, express or implied, or assume any legal liability regarding the correctness, accuracy, completeness or reliability of this publication. Any digital data and software supplied with this publication are subject to the licence conditions. The data are supplied on the understanding that they are for the sole use of the licensee, and will not be redistributed in any form, in whole or in part, to third parties. Any references to proprietary software in the documentation, and/or any use of proprietary data formats in this release, do not constitute endorsement by the ERCB/AGS of any manufacturer's product. If this product is an ERCB/AGS Special Report, the information is provided as received from the author and has not been edited for conformity to ERCB/AGS standards. When using information from this publication in other publications or presentations, due acknowledgment should be given to the ERCB/AGS. The following reference format is recommended: Bachu, S., Buschkuehle, M., Haug, K., Michael, K. (2008): Subsurface characterization of the Pembina-Wabamun acid-gas injection area; Energy Resources Conservation Board, ERCB/AGS Special Report 093, 60 p. -

Geochemical Studies of Natural Gas, Part 1

, ~ ( j ? j f GeoehelDieaI Studies of Natural Gas I PART m. INERT GASES IN WESTERN CANADIAN NATURAL GASES* ~ By BRIAN HITCHONt -j (This is the last of a Series of three Parts presented by the author tor publication in the Journal. Parts I I, and II appeared, in the Summer and Fall issues respectively.) ABSTRAGr 1 INTRODUcrION GEOCHEMISTRY AND ORIGIN OF In natural gases, the stratigra NITROGEN l phic and geographic variations in J T HIS paper is the third aud final Downloaded from http://onepetro.org/JCPT/article-pdf/2/04/165/2165406/petsoc-63-04-03.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 1 the contents of both nitrogen and part of a series concerned with Before considering this subject heIiwn are of geochemical interest, further it is very important to con although only helium is of com the geochemistry of natural gas in 1 mercial importance. Nitrogen may Western Canada. It is a discussion sider the units in which the analy l originate from a great variety of of the inert gases nitrogen and he tical data are reported. Ideally, sources, including air, either orig lium. The first paper (1) dealt knowledge of the mass of the in J inally trapped in the sediments or '~ introduced dissolved in percolating with the hydrocarbons and the sec dividual components of natural groWldwaters, the denitrification of ond (2) with the acid gases. Due gases in the sedimentary basin is nitrogenous compounds or the de to their generally unreactive na desirable. From the reports of cay of certain radioactive minerals. ture, chemically, compared to hy Buckley and his co-workers (5) it In contrast, there exist radioac drocarbons or the acid gases, both may be surmised that the bulk of tive sources for all natural helium, nitrogen and helium are common the material is methane, with much and thus the problem of the migra lesser amounts .of other components. -

Cross-Section of Paleozoic Rocks of Western North Dakota

JolfN P. BLOEMLE N. D. Geological Survey NORTH DAKOTA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WILSON M. LAIRD, State Geologist Miscel1aneous Series No. 34 CROSS-SECTION OF PALEOZOIC ROCKS OF WESTERN NORTH DAKOTA BY CLARENCE G. CARLSON Reprinted from Stratigraphic Cross Section of Paleozoic Rocks-Oklahoma to Saskatchewan, 1967: The American Association of Petroleum Geologists Cross Section Publication 5, p. 13-15, 1 Plate Grand Forks, North Dakota, 1967 NORTH DAKOTAI (Section E-F. Plate 5) C. G. CARLSON' Grand Forks, North Dakota INTRODUCTION which, in ascending order, are the Black Island, Icebox, The North Dakota segment of the cross section was and Roughlock. The Black Island generally consists of constructed with the base of the Spearfish Formation as clean quartzose sandstone, the Icebox of greenish-gray, noncalcareous shale, and the Roughlock of greenish-gray the datum. However, the Permian-Triassic boundary to brownish-gray, calcareous shale or siltstone. now is thought to be within redbeds of the Spearfish The Black Island and Icebox Formations can be Formation (Dow, 1964). If this interpretation is cor traced northward to Saskatchewan, but they have not rect, perhaps as much as 300 ft of Paleozoic rocks in been recognized as formations there and are included in well 3 and smaller thicknesses in wells I, 2, and 4-12 an undivided Winnipeg Formation. The Black Island are excluded from Plate 5. pinches out southwestward because of nondeposition Wells were selected which best illustrate the Paleozo along the Cedar Creek anticline, but the Icebox and ic section and its facies changes in the deeper part of Roughlock Formations, although not present on the the Williston basin.