Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWS RELEASE Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation

March 1, 2010 www.jogmec.go.jp NEWS RELEASE Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation Division in charge: Metals Finance Dept. Nishikawa Fax: +81-44-520-8720 PR in charge: Administration Dept. Uematsu Fax: +81-44-520-8710 JOGMEC provides equity financing for a rare metal exploration project in the Solomon Islands Japan Oil, Gas & Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC, President: Hirobumi Kawano), has provided equity capital finance of 30% to an exploration subsidiary of Sumitomo Metal Mining Co., Ltd. (SMM, President: Nobumasa Iemori). The subsidiary has been established for the purpose of promoting a rare metal (nickel and cobalt) exploration project conducted in the Solomon Islands by SMM. SMM has conducted explorations in the Solomon Islands since obtaining exploration rights in 2006. According to the result of the explorations, potential of rare metal (nickel and cobalt) deposit has been recognized. JOGMEC has provided various types of supports so far, and now upon receiving the request by SMM we have decided to provide financing for the purpose of reducing country risk and providing technological support, with the aim of ensuring development proceeded. This is the first financing project for the metals resources sector of JOGMEC since it was established. JOGMEC plans to continue to provide active financing support to Japanese companies proceeding with exploration projects in overseas, in order to ensure a stable supply of metal and mineral resources. 1 ■Corporate Data ・Company name: Sumiko Solomon Exploration Co.,Ltd. ・Ownership/ -

Gender and Investment Climate Reform Assessment in Partnership with Ausaid

IFC Advisory Services in East Asia and the Pacific Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Solomon Islands Gender and Investment Climate Reform Assessment In Partnership with AusAID Public Disclosure Authorized January 2010 Sonali Hedditch & Clare Manuel © 2010 International Finance Corporation 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC 20433USA Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.ifc.org The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of IFC or the governments they represent. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of IFC concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Gender and Investment Climate Reform Assessment Solomon Islands Preface and Acknowledgements This Report is the result of collaboration between the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group. The Report has been produced for: • The Solomon Islands Government, primarily the Ministries of Commerce and Finance: to make recommendations for reform actions for Government to further enable women in Solomon Islands to participate effectively in the country’s economic development. • The International Finance Corporation: to inform its support to the Solomon Islands Regulatory Simplification and Investment Policy and Promotion Program and ensure that gender issues are incorporated in the program’s design and implementation. • AusAID: to assist development programs to mainstream gender and to enable women to benefit equitably from improvements in the business climate. -

Malaita Province

Environmental Assessment Document Project Number: 46014 June 2013 Solomon Islands: Provincial Renewable Energy Project Fiu River Hydropower Project – Malaita Province Initial Environmental Examination The Initial Environmental Examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AMNH American Museum of Natural History BMP Building Material Permit CBSI Central Bank of Solomon Islands CDM Clean development mechanism CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species DSC Design and supervision consultant EA Executing agency ECD Environment and Conservation Division (of MECDM) EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EIS Environmental Impact Statement EHSG Environmental Health and Safety Guidelines (of World Bank Group) EMP Environmental Management Plan EPC Engineer Procure and Construct ESP Environmental Sector Policy FRI National Forest Resources Inventory GDP Gross Domestic Product GFP Grievance focal point GNI Gross National Income GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism HDPE High density polyethylene HDR Human Development Report HSP Health and Safety -

Isabel Province

159°15'E 159°30'E 159°45'E 160°00'E Reta Is Malakobo Is Malakobi Is Sesehura Faa Is ISABEL PROVINCE BubulinaBubulinaBubulina Pt PtPt Naghono Is Sesehura Is EAST SOLOMON ISLANDS ((( ((( BoliteiBoliteiBolitei Bani Leghahana Is TOPOGRAPHIC MAP SERIES 2005 wqq AHCAHC SCALE 1:150,000 R api Rar KesuoKesuoKesuo Logging LoggingLogging Camp CampCamp 5 0 10 20 ((( ((( KesuoKesuoKesuo 1 11 (((( (((( R kilometres u KesuoKesuoKesuo Pt PtPt h g e u h Elevation (m) g E Is Anchorage ; Town / Builtup Area Capital Cities -- #(### -- #### 0 to 200 600 to 800 1200 to 1400 (((( MaptainMaptain (((( MaptainMaptain Barrier Reef Coastline Airports Large Settlement (( Sikale 200 to 400 800 to 1000 1400 to 1600 Bay Reef Buildings Medium Settlement ((( (((( (((( 400 to 600 1000 to 1200 GhahiratetuGhahiratetu PtPt Rivers / Lake Roads Small Settlement (((( GhahiratetuGhahiratetu PtPt SisigaSisigaSisiga Pt PtPt #### r Mountains f Tracks Unknown Settlement #### ve Ghatere qq i ((( R ((( SisigaSisigaSisiga e Bay Depth (m) al qq ik NadinaNadinaNadina Pt PtPt NAPNAPw Swamp Trail Education Facilities qq S NadinaNadinaNadina Pt PtPt ver 0 to 100 1000 to 2000 3000 to 4000 re Ri Ghasetatauro Rock Is Ghate Orchard Bridges } Health Facilities w SoviriSoviriSoviri Pt PtPt Kes uo 100 to 1000 2000 to 3000 4000 to 5000 C Crop Language Areas o A A ve Ghehe Or Estrella Bay Grid...................................Longitude/Latitude WGS84 Caution: The depiction of an area name on this map is not to be taken as evidence of customary land ownership. Ghehe Anchorage SalenaSalenaSalena Pt PtPt Projection................................................Geographical ; Prepared, printed and published by the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Survey based upon reductions of Australian Department of #(#(#(#( ((((SakalenaSakalenaSakalena Spheriod..........................................................WGS84 #(#(#(#( ((((SakalenaSakalenaSakalena #(#(#(#( DovanareDovanare Defence data. -

Indigenous People Development of SIRA Executive

Social Assessment- Indigenous People Development of SIRA Executive: People who will be involved in training and capacity building and setting up of SIRA. Indigenous people of the Project Area Solomon Islands The Solomon Islands is one of the Melanesian countries in the Pacific Region. It is inhabited by more than 500,000 people. The population consists of the three major races, the Polynesians, Micronesian and the Melanesians. Inter-marriage to Europeans and Asians has accounts for certain percentage of the total population as well. There are 9 main Provinces scattered across the ocean close to Vanuatu and PNG and more than 1000 small Islands and Islets formed by volcanic activity thousands of years ago. The Islands are mainly volcanic and raised limestone Islands. The country is known for its pristine forest and marine resources as the centre of Biodiversity hot spots next to PNG and some South East Asian countries like Indonesia. However over-harvesting, unsustainable logging and prospecting (mining) are continuous and emerging threats to the biodiversity. Conservation and resource management programs are in placed to ease some of the negative impacts impose by these threats. Methods used by communities are integrating traditional knowledge and modern science to protect the resources. Most of these programs however can be found in most remote areas of the country, which is very challenging. Despite the challenges, efforts have been made in encouraging networking and partnership to manage the challenges and utilize the potentials available. Thus Solomon Islands Ranger Association (SIRA) was established and intended to play the role of supporting the local village rangers that employed by Community- based Organization (CBOs). -

Coelaenomenoderini Weise 1911

Tribe Coelaenomenoderini Weise 1911 Coelaenomenoderini Weise 1911:51 (catalog). Weise 1911b:76 (description); Maulik 1915:372 (museum list); Handlirsch1925:666 (classification); Uhmann 1931g:76 (museum list), 1931i:847 (museum list), 1940g:121 (claws), 1951a:25 (museum list), 1954h:181 (faunal list), 1956f:339 (catalog), 1958e:216 (catalog), 1959d:8 (scutellum), 1960b:63 (faunal list), 1960e:260 (faunal list), 1961a:23 (faunal list), 1964c:169 (faunal list), 1964(1965):255 (faunal list), 1966d:275 (noted), 1968a:361 (faunal list); Gressitt 1957b:268 (South Pacific species), 1960a:66 (New Guinea species); Gressitt & Kimoto 1963a:905 (China species); Würmli 1975a:39 (genera); Seeno & Wilcox 1982:163 (catalog); Chen et al. 1986:596 (China species); Jolivet 1988b:13 (host plant), 1989b: 310 (host plant); Gressitt & Samuelson 1990:259 (New Guinea species); Jolivet & Hawkeswood 1995:153 (host plant); Cox 1996a:169 (pupa); Jolivet & Verma 2002:62 (noted); Mohamedsaid 2004:168 (Malaysian species); Staines 2004a:313 (host plant); Chaboo 2007:176 (phylogeny); Borowiec & Sekerka 2010:381 (catalog); Bouchard et al. 2011:78, 513 (nomenclature); Liao et al. 2015:162 (host plants). Pharangispini Uhmann 1940g:122. Uhmann 1951a:36 (museum list), 1958e:216 (catalog), 1964a:456 (catalog); Gressitt 1957b:275 (South Pacific species); Gressitt & Samuelson 1990:272 (synonymy); Staines 1997b:418 (Uhmann species list); Jolivet & Verma 2002:62 (noted); Bouchard et al. 2011:513 (nomenclature). Type genus:Coelaenomenodera Blanchard. Balyana Péringuey 1898 Balyana -

ISABEL PROVINCE V G #### I #(### H #### R I

158°00'E 158°15'E 158°30'E 158°45'158°45'E 159°00'E Suki Is Maduko Reef Is Dughai shoal Malaghara Is LaveLaveLave Pt PtPt Kolohirio Is Nohabuna Is GahuruGahuru PtPt Paregho Shoal M Pareipoga Is Bates Is Telenetera Is Zaka Is Malakobi Is Remark Is A Kologilo Passage Sibau Is N Ghebira Is ge I ssa Kologilo Is Popu Is pa pu P A K A K A L E Po N BikoliaBikoliaBikolia Pt PtPt Hihibana Is Kologhose Is G Zabana Is Korapagho Is S Kale Is T ZABANA Vakao Is Arnavon Is R MT BEAUMONT Kukudaka Reef P A OPU C HANNE L Gateghe Is Kerehikapa Is I T Viketonggana Is ((( KupikoloKupikoloKupikolo Sesehura Ite Is ((( KupikoloKupikoloKupikolo ! KupikoloKupikoloKupikolo ! MT SEARS Golora Is (((( Sesehura Fa Is (((( KerehikapaKerehikapaKerehikapa Rapita Is (((( (((( RitamalaRitamala V A H A (((( ValidoValidoValido Pt PtPt (((( ValidoValidoValido Pt PtPt Legaha Is (((( Higere Is Retu Is Kakatina Is Sekoa Reef Hataheta Is Kumarara Hira Is !! Sogumao Ite Is ! Kumarara Is ! Kia Hetaheta Is Sogomauhiti Is IsaisaoIsaisaoIsaisaoIsaisao Pt PtPtPt Bay 7°30'S IsaisaoIsaisaoIsaisaoIsaisao Pt PtPtPt 7°30'S Sogumao Is Libeiena Is Zaosodu Reef E M A LitunaoLitunaoLitunao Pt PtPt #### #(### T O B I ####B A BARORA FA ((( D ((( TobiTobiTobi A Penrose TobiTobiTobi H Omona Is Zaoponoe Reef Patches #(### A Z A M O T E #### I R O Paenaha Fa Is Paenaha Ite Is V A R U K O I L O Ghizunabeana BoeBoeBoe Pt PtPt Ghanitapi Reef Passage P A Z E G H E R E Ghahipakagili Reef Memehana Fa Is Hulbrow Is Bitters Is B A H A N A Draper Is #### Memehana ite Is #(### PaehenaPaehenaPaehena Pt PtPt -

Beachhead by Schooner in the Solomonsl the Second Allied Invasion of Choiseul Howard E

New Mexico Quarterly Volume 32 | Issue 3 Article 5 1962 Beachhead by Schooner in the SolomonsL The Second Allied Invasion of Choiseul Howard E. Hugo Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq Recommended Citation Hugo, Howard E.. "Beachhead by Schooner in the SolomonsL The eS cond Allied Invasion of Choiseul." New Mexico Quarterly 32, 3 (1962). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq/vol32/iss3/5 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Press at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Quarterly by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hugo: Beachhead by Schooner in the SolomonsL The Second Allied Invasion 129 HowardE.Hugo BEACHHEAD BY SCHOONER IN THE . " SOLOMONS: THE SECOND ALLIED INVASION OF CHOISEUL Choiseul Island lies between Bougainville and Santa Isabel Island in the Solomons. For the reader whose orientation is based on Guadal canal, the southeast comer of Choiseul is one hundred and eighty miles from Cape Esperance, the northwest tip of that famous island. The topography of Choiseul is like that of any member of the Solomon "group. Its ninety-by-twenty mile area is a mountainous interior rising to three thousand feet. The high lands gradually slope off in a series of jungle-covered escarpments to sandy beaches and coral -cliffs that outline a long, irregular perimeter. A barrier reef runs parallel to the northern coast. The southern shoreline contains innumerable coves, bays, and islets. Except for a Ctoken landing by Marine Raiders, executed as diversion "during the Bougainvi1Ie attack in October, 1943,Jhe island saw little of the South Pacific War. -

Solomon Islands Fisheries Bibliography

Solomon Islands Fisheries Bibliography Robert Gillett March 1987 Document 87/1 FAO/UNDP Regional Fishery Support Programme TABLE of CONTENTS I. Introduction ............................................................................................ iii II. Location of reference ............................................................................ v III. References listed alphabetically by author ....................................... 1 IV. References listed by subject .............................................................. 27 Aquaculture ............................................................................... 27 Annual reports ........................................................................... 27 Baitfish ....................................................................................... 28 Beche-de-mer ........................................................................... 29 Boats and Boatbuilding.............................................................. 29 Bottomfish ................................................................................. 30 Charts, Topography, and Boundaries ....................................... 31 Computer ................................................................................... 32 Coral .......................................................................................... 32 Crayfish-lobster.......................................................................... 32 Fish handling and processing .................................................. -

Stimulating Investment in Pearl Farming in Solomon Islands: Final Report

Stimulating investment in pearl farming in Solomon Islands: Final report Item Type monograph Publisher The WorldFish Center Download date 03/10/2021 22:05:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/25325 Stimulating investment in pearl farming in Solomon Islands FINAL REPORT August 2008 Prepared by: The WorldFish Center, Solomon Islands, and The Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Solomon Islands Supported by funds from the European Union Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources CONTENTS 1 THE PROJECT...............................................................................................1 2 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................2 2.1 Pearl farming in the Pacific.............................................................................2 2.2 Previous pearl oyster exploitation in Solomon Islands...................................4 3 THE PEARL OYSTERS................................................................................5 3.1 Suitability of coastal habitat in Solomon Islands............................................5 3.2 Spat collection and growout............................................................................6 3.3 Water Temperature.........................................................................................8 3.4 White-lipped pearl oyster availability.............................................................8 3.5 The national white-lip survey.........................................................................8 3.6 -

Solomon Islands Blooming Flower Industry

Solomon Islands blooming flower industry. A smallholder’s dream November 2009 Solomon Islands Flower Industry: A Case Study of Agriculture for Growth in the Pacific Agriculture for Growth: learning from experience in the Pacific Solomon Islands Flower Case Study Prepared by Anne Maedia and Grant Vinning The views expressed in this paper do not represent the position of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.The depiction employed and the presentation of material in this paper do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations covering the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities or concerning the deliberations of its frontiers or boundaries. 2 Solomon Islands Flower Industry: A Case Study of Agriculture for Growth in the Pacific Table of contents Acknowledgements 4 Acronyms 5 Executive summary 6 1. Introduction 9 1.1 Case study background 9 1.2 Country economy and agriculture sector 10 1.3 National policy framework 13 1.4 Floriculture sector in Solomon Islands 15 2. Study methodology 17 3. Key findings and discussions 18 3.1 Value chain 18 3.2 SWOT 27 3.3 Technical, institutional, and policy issues 30 3.4 Maintaining competitive advantage 32 3.5 Options for growth 35 4. Conclusions 38 5. Bibliography 39 3 Solomon Islands Flower Industry: A Case Study of Agriculture for Growth in the Pacific Acknowledgements This paper is based on countless interviews and discussions with producers, sellers and buyers of floriculture products at the Honiara Central Market. -

Do Your Part, Disaster Is Everybody's Business

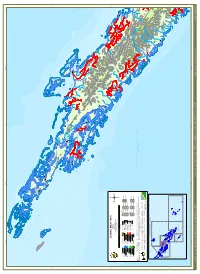

THE SOLOMON ISLANDS NATIONAL EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTRE [NEOC] P.O.Box 21 Tel: 00 677 27936/27063/955 Mob: 00 677 749741 Fax: 00 677 27060/24293 Email: [email protected] SI NEOC NATIONAL SITUATIONAL REPORT *************************************************************************************************************** National Emergency Operations Centre National Disaster Management Office Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Management and Meteorology Solomon Islands Government Honiara *************************************************************************************************************** SI NEOC SITUATION REPORT NUMBER 08 EVENT SEVERE FLASH FLOODS AND LANDSLIDES Compiled by: Dated issued: Time issued: Next update: George Baragamu 14th April 2014 12:00Hrs 12:00Hrs, 16th April 2014 From: To: N-DOC & NDC Chairs and Members, P-DOC National Emergency Operation Centre and PDC Chairs and Members, PEOCs Honiara Copies: NDMO Stakeholders, Donor Partners, Local Solomon Islands & International NGOs, UN Agencies, Diplomatic Agencies, SIRPF, SIRC and SI Government Ministries and all SI Government Overseas Missions 1. INFORMATION OF PEOPLE Total affected Total affected Total Male Total female Total children population: Household: affected: affected: affected: Estimate 52,000 5465 5188 Number of deaths: No of people missing: No of people Total people displaced: 21 2 injured: 10,653(these are people from 18 : Honiara Evacuation Centres HCC and GP 2 : Isabel combined. Source: SIRC) 2 : Guadalcanal 2. SITUATION DESCRIPTION All new information is in red coloured font. The current situation now is that the floods are now recedes in almost all the flood inundated areas, and humanitarian responses are slowly being delivered by the Government and the Humanitarian Actors. Initial Damaged Assessments (IDA) is now being undertaken by the Honiara City Council and Guadalcanal Province whilst Detail Sectoral Assessments (DSA) is being conducted by the responsible Government Ministries through the relevant Sectors.