Rhetorical Cartographies: (Re)Mapping Urban Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 Restore Omaha Program

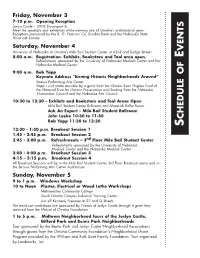

Friday, November 3 7-10 p.m. Opening Reception Joslyn Castle – 3902 Davenport St. Meet the speakers and exhibitors while viewing one of Omaha’s architectural gems. Reception sponsored by the B. G. Peterson Co, Dundee Bank and the Nebraska State Historical Society Saturday, November 4 VENTS University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Milo Bail Student Center at 62nd and Dodge Streets 8:00 a.m. Registration. Exhibits, Bookstore and Tool area open. E Refreshments sponsored by the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Medical Center 9:00 a.m. Bob Yapp Keynote Address “Turning Historic Neighborhoods Around” Strauss Performing Arts Center Yapp’s visit made possible by a grant from the Charles Evan Hughes Fund of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and funding from the Nebraska Humanities Council and the Nebraska Arts Council. 10:30 to 12:30 – Exhibits and Bookstore and Tool Areas Open Milo Bail Student Center Ballroom and Maverick Buffet Room Ask An Expert – Milo Bail Student Ballroom John Leeke 10:30 to 11:30 CHEDULE OF Bob Yapp 11:30 to 12:30 S 12:30 - 1:30 p.m. Breakout Session 1 1:45 - 2:45 p.m. Breakout Session 2 2:45 - 3:00 p.m. Refreshments – 3rd Floor Milo Bail Student Center Refreshments sponsored by the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Nebraska Medical Center 3:00 - 4:00 p.m. Breakout Session 3 4:15 – 5:15 p.m. Breakout Session 4 All Breakout Sessions will be in the Milo Bail Student Center 3rd Floor Breakout rooms and in the Strauss Performing Arts Center Auditorium Sunday, November 5 9 to 1 p.m. -

Nebraska's 2019-20 Approved Title I Schoolwide Programs

NEBRASKA'S 2019-20 APPROVED TITLE I SCHOOLWIDE PROGRAMS Building Reviewed District id Agency id District Name Agency Name Grade of Span Plan Plan Last Peer ESU CONSORTIA ESU SW PeerSW Review Yr. NDE TitleNDE I Consultant ESSA Monitoring Year Monitoring ESSA CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-003 ALCOTT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-004 HAWTHORNE ELEMENTARY K-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-005 LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL K-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-006 LONGFELLOW ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0018-000 HASTINGS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01-0018-008 WATSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-5 4/2017 2 3 CATHY 01-0123-000 SILVER LAKE PUBLIC SCHOOLS 09 01-0123-002 SILVER LAKE ELEMENTARY at BLADEN K-6 4/2018 3 1 TIM 02-0009-000 NELIGH-OAKDALE PUBLIC SCHOOLS 02-0009-004 WESTWARD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-2 4/2018 3 1 TIM 02-0009-000 NELIGH-OAKDALE PUBLIC SCHOOLS 02-0009-005 EASTWARD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3-6 4/2018 3 1 TIM 02-2001-000 NEBRASKA UNIFIED DISTRICT 1 02-2001-002 CLEARWATER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-6 4/2019 1 2 TIM 02-2001-000 NEBRASKA UNIFIED DISTRICT 1 02-2001-004 ORCHARD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-6 4/2019 1 2 TIM 02-2001-000 NEBRASKA UNIFIED DISTRICT 1 02-2001-006 VERDIGRE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK-6 4/2019 1 2 TIM 04-0001-000 BANNER COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 04-0001-002 BANNER COUNTY ELEMENTARY K-6 4/2019 1 2 CATHY 05-0071-000 SANDHILLS PUBLIC SCHOOLS 10 05-0071-002 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL AT HALSEY K-6 4/2017 2 3 PAT 06-0001-000 BOONE CENTRAL -

Papillion Creek Watershed Partnership

NPDES PERMIT (NER220000) FOR SMALL MUNICIPAL STORM SEWER DISCHARGES TO WATERS OF THE STATE LOCATED IN DOUGLAS, SARPY, AND WASHINGTON COUNTIES OF NEBRASKA NPDES PERMIT NUMBER 220003 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Submitted by: City of Papillion, Nebraska 122 East Third Street Papillion, NE 68046 May 2020 City of Papillion 2019 Annual Report May 2020 Permit number NER220003 Report of Certification “I certify under penalty of law that this document and all attachments were prepared under my direction or supervision in accordance with a system designed to assure that qualified personnel properly gathered and evaluated the information submitted. Based on my inquiry of the person or persons who manage the system or those persons directly responsible for gathering the information, the information submitted is to the best of my knowledge and belief, true, accurate, and complete. I am aware that there are significant penalties for submitting false information, including the possibility of fine and imprisonment for known violations. See 18 U.S.C. 1001 and 33 U.S.C 1319, and Neb. Rev. Stat. 81-1508 thru 81-1508.02.” 05/18/2020 Signature of Authorized Representative or Cognizant Official Date Alexander L. Evans, PE Deputy City Engineer Printed Name Title ii City of Papillion 2019 Annual Report May 2020 Permit number NER220003 1. BACKGROUND On July 1, 2017 the Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality (NDEQ) issued a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit NER210000 for Small Municipal Storm Sewer discharges to waters of the state located in Douglas, Sarpy, and Washington Counties of Nebraska. The co-permittees of the Papillion Creek Watershed Partnership (PCWP) currently authorized to discharge municipal storm water under this permit are Bellevue, Boys Town, Gretna, La Vista, Papillion, Ralston and Sarpy County. -

C:\Documents and Settings\User\

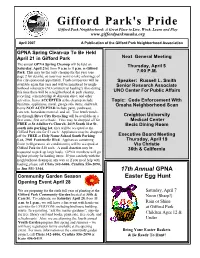

Gifford Park's Pride Gifford Park Neighborhood: A Great Place to Live, Work, Learn and Play www.giffordparkomaha.org April 2007 A Publication of the Gifford Park Neighborhood Association GPNA Spring Clean-up To Be Held April 21 in Gifford Park Next General Meeting The annual GPNA Spring Cleanup will be held on Thursday, April 5 Saturday, April 21st, from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. in Gifford Park. This may be the only cleanup for the year (see 7:00 P.M. page 2 for details), so you may want to take advantage of this city-sponsored opportunity. Trash compactors will be Speaker: Russell L. Smith available again this year and will be monitored by neigh- Senior Research Associate borhood volunteers (NO commercial hauling!) Also during this time there will be a neighborhood & park cleanup, UNO Center For Public Affairs recycling, a membership & donation drive, and other activities. Items ACCEPTED at the cleanup include Topic: Code Enforcement With furniture, appliances, metal, garage sale items, and trash. Omaha Neighborhood Scan Items NOT ACCEPTED include paint, yardwaste, concrete, hazardous material, and oil. Tree brush vouch- ers through River City Recycling will be available on a Creighton University first come, first serve basis. Tires may be dropped off for Medical Center FREE at St Adalbert's Church, 2619 South 31st St., Becic Dining Room south side parking lot; tires will be accepted at the Gifford Park site for $1 each. Appliances may be dropped off for FREE at Holy Name School South Parking Executive Board Meeting Lot, 2901 Fontenelle Blvd. Appliances containing Thursday, April 19 freon (refrigerators, air conditioners) will be accepted at Via Christie Gifford Park for $10 each. -

![Douglas County [RG230].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9050/douglas-county-rg230-pdf-1279050.webp)

Douglas County [RG230].Pdf

RG230 DOUGLAS COUNTY: Inventory of Collection SUBGROUP ONE DOUGLAS COUNTY SURVEYOR/ENGINEER, 1857-1915 MICROFILM, Reference Room, NSHS SERIES ONE THRU SERIES EIGHT Field Notebooks, 9 page boxes Surveyor’s Resolutions, 26 reels Surveyor’s Misc. Resolutions, 13 reels Topographical, Ownership, and Sectional Plans, 4 reels Plats and Blueprints, 22 reels Plats, 116 reels Land Plats, 13 reels Misc. Plats, 25 reels Miscellany, including road and bridge records, 18 reels SG1, SERIES ONE LAND PLAT BOOKS Roll #1, Book #1, T14-16N, Ranges 9E-13E Roll #2, Book #1, T14, R9E, Section 1 thru R16N, R9E, Sections 1-6, 8-17, 22-27, 34-36 Roll #3, Book #2, T14N, R10E, Sections 1 thru 12 T14N, R11E, Sections 1 thru 12 Roll #4, Book #3, T14N, R12E, Sections 1 thru 12 T14N, R13E, Sections 1 thru 11 Roll #5, Book #4, T15N, R10E, Sections 1 thru 36 T15N, R10E, Sections 10 thru Waterloo Roll #6, Book #5, T15N, R11E, Sections 1 thru 36 Roll #7, Book #6, T15N, R12E, Sections 1 thru 36 Roll #8, Book #7, T15N, R13E, Sections 1 thru 19 Roll #9, Book #8, T15N, R13E, Section 20 (West Omaha) thru T16N, R13E, Section 36 T15N, R13E, Section 35 (Riverview Park) T15N, R14E, Sections 6 & 7 T16N, R14E, Section 31 Roll #10, Book #9, T16N, R10E, Sections 1 thru 36 (included Elkhorn River) Roll #11, Book #10, T16N, R11E, Sections 1 thru 36 Roll #12, Book #11, T16N, R12E, Sections 1 thru 36 Roll #13, Book #12, T16N, R13E, Sections 2 thru 36 1 SG 1, SERIES TWO LAND PLATS, QUARTER SECTIONS Roll #14, NW, S1, T14N, R10E thru SE, S12, T14N, R10E Roll #15, NW, S1, T14N, R11E thru SE, S12, T14N, R11E Roll #16, NW, S1, T14N, R11E thru SE, S12, T14N, R12E Roll #17, NW, S2, T14N, R13E thru SW, S11, T14N, R13E Roll #18, NW, S1, T15, R9E thru SE, S23, T15N, R10E Roll #19, NW, S24, T15N, R10E thru SE, S12, T15N, R11E Roll #20, NW, S13, T15N, R11E thru SE, S36, T15N, R11E Roll #21, NW, S1, T15N, R12E thru SE, S16, T15N, R12E Roll #22, NW, S18, T15N, R13E thru SE, S36, T15N, R13E Roll #23, NW. -

Race in America Fr. Hendrickson's First Year

Race in Fr. Hendrickson’s First Year America Drug Shortages Totally RaD Marriage, Family and the Catholic Church Summer 2016 Architectural rendering looking north at the new complex, with Boys Town National Research Hospital (not part of the sale) silhouetted at left in the foreground and the pedestrian bridge at right. (Alley Poyner Macchietto Architecture) A Prescription for the Future A local developer has agreed to purchase the CHI Health Creighton University Medical Center property at 30th and California streets and plans to redevelop it into 650 to 700 apartments with retail space and an 850-foot long pedestrian bridge over the North Freeway to Creighton’s main campus. The news was met with a healthy dose of excitement from Creighton and community leaders. Creighton President the Rev. Daniel S. Hendrickson, S.J., called the announcement “a great day for Creighton and the surrounding community.” Read more here. University Magazine Message from the President Volume , Issue Publisher: Creighton University; Rev. Daniel More than , Creighton S. Hendrickson, S.J., President. Creighton graduates received degrees during University Magazine staff: Jim Berscheidt, commencement ceremonies in Chief Communications and Marketing O cer; Glenn Antonucci, Sr. Director of May, and we wish them well as Communications; Rick Davis, Director of they pursue professional careers, Communications; Sheila Swanson, Editor; Cindy Murphy McMahon, Writer; Nichole volunteer opportunities, and post- Jelinek, Writer; Adam Klinker, Writer; Emily graduate education. Rust, Writer. This annual academic tradition is a good Creighton University Magazine is published reminder to us all of the importance of in the spring, summer and fall by Creighton remaining lifelong learners. -

Omaha's Lakeland

\ .. I i j, Omaha Skyline " 1942 Manual of Civic Improvements MAHA owes much to work started some years past and reports of the Civic Improvement Council, the Survey of the National Recreation (9Association, the Carter Lake Development Society and the City Plan ning Commission. Their efforts have been an inspiration to the Mayor and City Council of this Administration. We also acknowledge and wish to thank the National Parks Service, the Works Projects Adminisrrarion and the Civilian Conservation Corps (Local, State and National) for their help and assistance. Finally we are indebted to all departments for the services of their willing 'Workers and for the technical help of their skilled experts, consultants and I, advisors. Recreation program by Mayor Dan B. Butler , .. Page 2 Park Improvements by Commissioner Roy N. Towl Page 8 Boulevards by Commissioner John Kresl Page 18 Airport Improvements by Commissioner Harry Knudsen Page 24 Public Improvements by Commissioner Harry Trustin Page 26 Police - Safety by Commissioner Richard W. Jepsen , Page 28 Fire Department by Commissioner Walter Korisko. .. ....... .. .. Page 30 - Photo b:-' Hodes SOUTH ENTRANCE CITY HALL , Eighteenth and Farnam Streets I Front cover photograph, by COtty· teJ'Y of the National Parks Service, Dixtrict offi,ce, Omaha, Nebraska Back cover photograph hy c01lr les)' of U7alter Crdig f{alj./MICS by IL\lOdl E~(;JUVI N'; C,1;IJJ'.\N"Y, Omaha Printcd by n<>lJ"I.,IS Pm;>,'Tl.>';'; (iHfh\:.;Y, ()111.1!l,1 Supervised Recreation The Omaha Recrearion Deparrment was created Participation in the departmental program has in for the purpose of providing a city-wide, carefully creased materially year by year with, of course, the planned recreational program for the cirizens of exception of young men of military age who have Omaha, regardless of age. -

Neighborhood Parks Rehabilitation Plan

.. .. NEIGHBORHOOD liliiii PARKS -_. REHABILITATION - PLAN: ~ 1997-2003 A NEEDS ASSESSMENT PROCESS AND CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM FOR OMAHA'S NEIGHBORHOOD PARKS DEVELOPED BY THE CITY OF OMAHA DEPARTMENT OF PARKS, RECREATION, AND PUBLIC PROPERTY AND RDG CROSE GARDNER SHUKERT NOVEMBER, 1997 PR250 TABLE OF INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1 NEIGHBORHOOD PARK CONTENTS REHABILITATION, 1986-96 3 AVAILABLE RESOURCES 6 THE PLANNING PROCESS 8 REHABILITATION PROGRAM AND BUDGET 13 CAPITAL SCHEDULE 14 APPENDIX 1 Roster ofProject Team APPENDIX 2 Parks Evaluated During Evaluation Process APPENDIX 3 Park Rehabilitation Program and Statements of Probable Costs APPENDIX 4 Park Evaluation Form APPENDIX 5 Park Evaluation Summary C> C>'" '" '" ~ 'E .~ '"""~ ~ ""c 2: i::'" " 2': ....)"'" ~ 2< ""'i' ..g .g "".~ ~'" ~ ~'.'-,''',- the largest number ofindividual open spaces of "l;f-'."-c_, all park categories in the city's system. The city has over 147 individual properties categorized as neighborhood parks, encompassing over 1,200 acres. These parks provide a wide varie ty ofrecreational facilities, including play equipment, picnic areas, ballfields, trails, basket ball and tennis courts, water recreation, and multi-use open space. However, the sheer number and dispersion ofthese £~cilities make § their maintenance and ongoing improvement a difficult challenge for the city's Parks, Recrea .. tion, and Public Property Department. In recognition ofthe need to rehabilitate the city's neighborhood parks in a systematic way, the Department ofParks, Recreation, and Pub lic Property established a specific funding cate gory for neighborhood parks within the Recre ation and Culture Bond funds authorized by Omaha's voters in 1986, 1992, and again in !iii 1996. Neighborhood park investment has been = guided by a series offive to six-year plans, eval uating neighborhood park conditions and pro gramming funds to those parks most in need of eighborhood parks are a critical rehabilitation. -

Celebrating Our Thriving Midtown Community

2019-2020 Business Guide and Directory for the Midtown-Omaha Community Celebrating our thriving Midtown community www.MidtownBusinessAssociation.org . SERVING NEBRASKA From leadingthe worldwidefightagainstEbola to serving Nebraskans across the stateto attracting the world’stop facultyand students, UNMC is everonthe forefrontofbreakthroughs forlife. About half of Nebraska’sphysicians, dental professionals, pharmacists, bachelor’s-degreed nurses and allied health professionals graduated from UNMC. More than 250 Nebraskans will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer eachyear.UNMC’ssuperteam of clinicians and scientists is working to develop the next generation of treatments forthis devastating disease. Along with ourprimary clinical partner,NebraskaMedicine, $4.8 UNMC hasanannual $4.8 billion impact on thestate’s economy. BILLION Each year we generate$165.1million in taxrevenue. Through its iEXCELSM initiative, UNMC is enhancing connectivity and interdisciplinaryeducation across the state through the strategic installation of iWalls in Omaha, Scottsbluff, Kearney, Lincoln and Norfolk. Learnmoreat unmc.edu/servingnebraska MIDTOWNCROSSING.COM 0000076779-01 MIDTOWN BUSINESS ASSOCIATION DIRECTORY Index Welcome 6 Board members 8 MBA – Who we are 10 Community involvement 11 Entrepreneurial scholarship 12 Neighborhood improvement award 14 New to Midtown 16 Midtown dining 18 Life in Midtown 23, 26 Midtown Map 24 Pillars of MBA 28 Business listing Categorical 35 Alphabetical 46 KENT SIEVERS 4 2019-2020 Midtown Business Association Directory Blackstone Corner Opening Winter 2019 TheTraveler Apartments Opening Winter 2020 402.991.1800 greenslateomaha.com PRESIDENT’S WELCOME Advocating for a healthy Midtown business community reetings, Midtown! As I think of Gwords to write, the first thing that comes to mind is how proud I am to be a part of this community and organization. -

Industrial Flex Bldg

FOR SALE INDUSTRIAL FLEX BLDG 2213 MILITARY AVENUE | OMAHA, NE 68111 SALE INFO & PROPERTY DETAILS • Building Size: 4,576 SF • Ideal for fabricator, painting, construction or woodworking • Sale Price: $300,000; $65.56 PSF company • 4,576 SF of warehouse space • Five parking stalls in rear • Two dock high doors • HVAC installed in 2015 • One 10’ drive-in door www.cbre.us/omaha Included in Sale INDUSTRIAL FLEX BUILDING GRAHAM NABITY Associate +1 402 697 5814 [email protected] MAPLE STREET SITE TREET S D N 52 DODGE STREET TO Minnie Lusa Florence Historical District & Belvedere North Point Florence EPPLEY Blvd AIRFIELD Miller Park Arthur C Storz Expy Fort Omaha Sherman Historical District Sorenson Pwy Central Park Collier Place Monmouth Park Ames Ave The Town of Saratoga CARTER Bedford Place LAKE, IA Malcolm X Memorial Neighborhood Kountze Place N 30th Street Benson & Benson North Downtown 24th Historical SITE and District Lake Historic District Highlander Development Blondo Street Long School Orchard Prospect Place Neighborhood Hill Hamilton Street Bemis Park Kellom Heights Cuming Street N 30th St University of Cuming Street Creighton TD Dental School Ameritrade Park NoDo The Atlas Redevelopment District N 10th St Gifford Park Century Dundee-Happy 10 th Street Link COUNCIL Hollow Center Joslyn Historical District Castle OMAHA BLUFFS, Omaha’s Central Clarkson Dodge Street Dodge Street Hospital Business District Midtown Douglas Street IA Park Heartland College Blackstone Crossing of America 30th Street Park Omaha District East Farnam Street Steel University of Castings Redevelopment Nebraska Medical Center The Old The Market 18th Street LeavenworthLeavenworth Street Leavenworth Street Project 10th Street 42nd Street Pacific Street Little Field Club Italy 081219au © 2019 CBRE, Inc. -

Restore Omaha Sponsors Restore Omaha Is a Grassroots Effort

11:15 to 11:45 a.m. – Lunch 11:45 – 12:45 p.m. – Keynote Speaker: Patricia H. Gay “Life in the Big Easy: Lessons Learned for Any City” l room 120 Patricia H. Gay, Executive Director, Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans Sponsored by AIA Omaha and Metropolitan Community College Foundation 1 – 2 p.m. – Session 2 National Register or National Historic Landmark? Why and Where do I Begin? l OPENING RECEPTION room 101 Friday, March 2 Alesha Hauser, Historian, LEED AP BD+C, National Park Service The Barnard Flats Sponsored by the Nebraska State Historical Society Foundation 804 Park Ave. Omaha, Nebraska The Evolution of an Omaha Landmark: The Historic Renovation of the Piano 7–10 p.m. Building l room 120 Conference Schedule Christina A. Jansen, Project Manager; Alley Poyner Macchietto Architecture Sponsored by Omaha Urban Neighborhoods an advocate of historic urban neighborhood commercial districts SATURDAY , MARCH 3 8 a.m. REGISTRATION and EXHIBITS OPEN American, New and Improved: A History of Modern Architecture l room 123 Paula A. Mohr, Architectural Historian, Iowa State Historic Preservation Office 9 a.m. Opening Session – A Labor of Love: The 20-year restoration of the Joel Sponsored by Tangerine Designs Kitchens & Baths N. Cornish residence by Gina Basile and Arnie Breslow l room 120 Sponsored by Critter Control of Omaha Better Restoration Through Chemistry: Why Do Things Fall Apart? l room 122 Julie A. Reilly, Conservator 9:45 – 10:45 a.m. – Session 1 Ups and Downs of Chimneys l room 121 The Electrical Code & the Vintage Home l room 101 Nate Griffith, owner and refurbisher of 4 vintage houses Tom Taylor, Electrical Contractor 2 – 2:30 – Exhibits. -

Omaha Spring Cleanup Schedule April 14, 2018

Omaha Spring Cleanup Schedule April 14, 2018 Neighborhood Association Location Benson Neighborhood Association Omaha Home For Boys (4343 N 52nd Street) Country Club Community Council Street at Country Club Ave & Grant & N 53rd Street (2303 Grant St.) Glenbrook Homeowners Association Glenbrook Clubhouse (7901 Vane Street) Hartman Avenue Neighborhood Association Behind Mount View Presbyterian Church (5308 Hartman Ave) Keystone Community Task Force Boyd Elementary School West parking lot (8314 Boyd Street) Linden Park HA & Lindenwood HA Ezra Millard School east parking lot (14111 Blondo Street) Maple Village Neighborhood Association Maple Village Country Club Pool parking lot (3645 Maplewood Blvd) Meadowbrook Homeowners Association Intersection of Seward Street & Louis Drive (1600 N 98th Street) Metcalfe-Harrison Neighborhood Association West parking lot at the Waypoint Church (1313 N 48th Ave.) Peony Park NA & Benson Gardens NA Hillside School (7500 Western Ave) Raven Oaks Improvement Association SE corner lot across from 5216 Raven Oaks Drive Saddle Hills Neighborhood Association Cul-de-sac at north 79th & Fort & Arlington Drive (7900 Arlington Dr.) Tire & Lead Acid Battery Host: Keystone Community Task Force Appliance Host: Peony Park NA & Benson Gardens NA Omaha Spring Cleanup Schedule April 21, 2018 Neighborhood Association Location Armbrust Acres HA, Leawood Southwest HA, Faithful Shepherd Presbyterian Church parking lot (2530 S 165th Ave) Western Trails Hidden Ridge NA, Pacific Heights, Pacific Shaker Heights NA Banyan Hills HA, Cambridge Oaks HA, Spring Ridge Elementary parking lot (17830 Shadow Ridge Dr) Merrifield Village HA, Pacific Ridge HA, Spring Ridge HA Crescent Oaks Neighborhood Association Solution One Parking Lot (14703 Wright Street) Harvey Oaks Homeowners Association Harvey Oaks Elementary parking lot (15228 Shirley St) Mission Hills HA, Mission Park HA, Autumn St.