Searching for the Muse: Changing Inspiration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICHARD FEREN 146B Rhodes Avenue – Toronto, on – M4L 3A1 416-787-0657 [email protected]

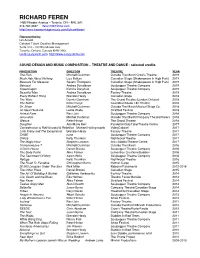

RICHARD FEREN 146B Rhodes Avenue – Toronto, ON – M4L 3A1 416-787-0657 [email protected] http://www.haemorrhage-music.com/richard-feren/ Represented by: Ian Arnold Catalyst Talent Creative Management Suite 310 - 100 Broadview Ave Toronto, Ontario Canada M4M 3H3 [email protected] http://www.catalysttcm.com SOUND DESIGN AND MUSIC COMPOSITION – THEATRE AND DANCE - selected credits PRODUCTION DIRECTOR THEATRE YEAR The Flick Mitchell Cushman Outside The March/Crow’s Theatre 2019 Much Ado About Nothing Liza Balkan Canadian Stage (Shakespeare In High Park) 2019 Measure For Measure Severn Thompson Canadian Stage (Shakespeare In High Park) 2019 Betrayal Andrea Donaldson Soulpepper Theatre Company 2019 Copenhagen Katrina Darychuk Soulpepper Theatre Company 2019 Beautiful Man Andrea Donaldson Factory Theatre 2019 Every Brilliant Thing Brendan Healy Canadian Stage 2018 The Wars Dennis Garnhum The Grand Theatre (London Ontario) 2018 The Nether Peter Pasyk Coal Mine/Studio 180 Theatre 2018 Dr. Silver Mitchell Cushman Outside The March/Musical Stage Co. 2018 An Ideal Husband Lezlie Wade Stratford Festival 2018 Animal Farm Ravi Jain Soulpepper Theatre Company 2018 Jerusalem Mitchel Cushman Outside The March/Company Theatre/Crow’s 2018 Silence Peter Hinton The Grand Theatre 2018 Daughter Ann-Marie Kerr Pandemic/QuipTake/Theatre Centre 2017 Confederation & Riel/Scandal & Rebellion Michael Hollingsworth VideoCabaret 2017 Little Pretty and The Exceptional Brendan Healy Factory Theatre 2017 CAGE none Soulpepper Theatre Company 2017 Unholy Kelly Thornton -

Founders Paul Bettis Luter Hansraj Kirsten Johnson Sherrie Johnson Jacoba Knaapen Daniel Macivor Don Mckellar Darren O'donnell

Barbara Fingerote Founders Paul Bettis Luter Hansraj Kirsten Johnson Sherrie Johnson Jacoba Knaapen Daniel MacIvor Don McKellar Darren O’Donnell Alex Poch-Goldin Nadia Ross Lisa Ryder Sarah Stanley Deanne Taylor Ken McDougall Award Award 1995 Richard Feren Bianca Jacobs Peter Lynch Bob Wallace Leslie Lester David Duclos Sky Gilbert Asher Turin Robin Fulford Veronika Hurnik Josie Le Grice Eileen O’Toole Jim Jones 1996 Daniel Brooks Kim Roberts Richard Vaughan Gwen Bartleman Alisa Palmer Bryan James Hillar Liitoja The Founders Andrew Scorer Joey Meyer Ron Kennell Jim Warren Rose Jacobson Franco Boni 1997 Tracy Wright Ahdri Zhina Mandiela Jonathan DaSilva Fiona Jones Alex Bulmer Maxine Bailey Sigrid Johnson --- David Anderson Ruthe Whiston Maria Costa Leah Cherniak Lynda Hill Cathy Gordon in memory of Mark 1998 Clare Coulter M. Nourbese Philips Ed Roy Rex Buckle Eryn Dace Trudell Jean Yoon Rebecca Picherak Ida Carnevale Andrea Lundy David Baile Jennifer Brewin Viv Moore Michael Waller Shields 1999 Winston Morgan Diane Roberts Elley-Ray Hennessy Will Sutton Sharon Di Genova Marion de Vries Peter Freund Toronto Arts Council Arturo Fresolone Derek Bruce Sally Szuster --- Keith Cole Chris Abraham Marcus Magdalena & Christine Moynihan / 2000 Sandra Hodnett Sally Han Roger West Jennifer Watkins Rose Stella Kimberly Purtell Michael Hollingsworth Peter Nikolic Natasha Parsons Wendy Krekeler Gregory Nixon Simon Heath Chris Prideaux Mira Friedlander 2001 Nancy Webster Naomi Campbell Adrien Whan David Hoekstra Jane Marsland Daniel David Moses Michelle -

Mongrel Media Presents

Mongrel Media presents a film by Wiebke von Carolsfeld Best First Canadian Feature, 2002 Toronto International Film Festival Best Screenplay, 2002 Atlantic Film Festival (Canada, 2002, 90 minutes) Distribution 109 Melville Ave. Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6G 1Y3 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] CAST Agnes Molly Parker Theresa Rebecca Jenkins Louise Stacy Smith Rose Marguerite McNeil Joanie Ellen Page Chrissy Hollis McLaren Dory Emmy Alcorn Ken Joseph Rutten Valerie Nicola Lipman Marlene Jackie Torrens Sandy Kevin Curran Mickey Ashley MacIsaac Sue Heather Rankin Evie Linda Busby Tavern Bartender Stephen Manuel Airport Bartender Jim Swansberg KEY CREW Distributor Mongrel Media Production Companies Sienna Films / Idlewild Films Director Wiebke von Carolsfeld Writer Daniel MacIvor Producers Jennifer Kawaja Bill Niven Julia Sereny Co-Producer Brent Barclay First Assistant Director Trent Hurry Director of Photography Stefan Ivanov B.A.C. Production Designer Bill Fleming Editor Dean Soltys Costume Designer Martha Currie Makeup Kim Ross Hair Joanne Stamp 2 Synopsis Marion Bridge is the moving story of three sisters torn apart by family secrets. In the midst of struggling to overcome her self-destructive behaviour, the youngest sister, Agnes, returns home determined to confront the past in a community built on avoiding it. Her quest sets in motion a chain of events that allows the sisters each in their own way to re-connect with the world and one another. Set in post-industrial Cape Breton, Marion Bridge is a story of poignant humor and drama. -

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave. Toronto, ON M6G 2A4 (416) 516 9574 [email protected] [email protected] Education M.A University of Guelph, School of English and Theatre Studies, August 2005 Thesis: Staging Memory, Constructing Canadian Latinidad (Supervisor: Ric Knowles) Recipient Governor-General's Gold Medal for Academic Achievement Ryerson Theatre School Acting Program 1980-82 Languages English, Spanish, French Theatre (selected) DIRECTING Two Birds, One Stone 2017 by Rimah Jabr and Natasha Greenblatt. Theatre Centre, Riser Project, Toronto The Thirst of Hearts 2015 by Thomas McKechnie Soulpepper, Theatre, Toronto The Art of Building a Bunker 2013 -15 by Adam Lazarus and Guillermo Verdecchia Summerworks Theatre Festival, Factory Theatre, Revolver Fest (Vancouver) Once Five Years Pass by Federico Garcia Lorca. National Theatre School. Montreal 2012 Ali and Ali: The Deportation Hearings 2010 by Marcus Youssef, Guillermo Verdecchia, and Camyar Chai Vancouver East Cultural Centre, Factory Theatre Toronto Guillermo Verdecchia 2 A Taste of Empire 2010 by Jovanni Sy, Cahoots Theatre Rice Boy 2009 by Sunil Kuruvilla, Stratford Festival, Stratford. The Five Vengeances 2006 by Jovanni Sy, Humber College, Toronto. The Caucasian Chalk Circle 2006 by Bertolt Brecht, Ryerson Theatre School, Toronto. Romeo and Juliet 2004 by William Shakespeare, Lorraine Kimsa Theatre for Young People, Toronto. The Adventures of Ali & Ali and the aXes of Evil 2003-07 by Youssef, Verdecchia, and Chai. Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, Edmonton, Victoria, Seattle. Cahoots Theatre Projects 1999 – 2004 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR. Responsible for artistic planning and activities for company dedicated to development and production of new plays representative of Canada's cultural diversity. -

Theatre and Transformation in Contemporary Canada

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by YorkSpace Theatre and Transformation in Contemporary Canada Robert Wallace The John P. Robarts Professor of Canadian Studies THIRTEENTH ANNUAL ROBARTS LECTURE 15 MARCH 1999 York University, Toronto, Ontario Robert Wallace is Professor of English and Coordinator of Drama Studies at Glendon College, York University in Toronto, where he has taught for over 30 years. During the 1970s, Prof. Wallace wrote five stage plays, one of which, No Deposit, No Return, was produced off- Broadway in 1975. During this time, he began writing theatre criticism and commentary for a range of newspapers, magazines and academic journals, which he continues to do today. During the 1980s, Prof. Wallace simultaneously edited Canadian Theatre Review and developed an ambitious programme of play publishing for Coach House Press. During the 1980s, Prof. Wallace also contributed commentary and reviews to CBC radio programs including Stereo Morning, State of the Arts, The Arts Tonight and Two New Hours; for CBC-Ideas, he wrote and produced 10 feature documentaries about 20th century performance. Robert Wallace is a recipient of numerous grants and awards including a Canada Council Aid to Artists Grant and a MacLean-Hunter Fellowship in arts journalism. His books include The Work: Conversations with English-Canadian Playwrights (1982, co-written with Cynthia Zimmerman), Quebec Voices (1986), Producing Marginality: Theatre 7 and Criticism in Canada (1990) and Making, Out: Plays by Gay Men (1992). As the Robarts Chair in Canadian Studies at York (1998-99), Prof. Wallace organized and hosted a series of public events titled “Theatre and Trans/formation in Canadian Culture(s)” that united theatre artists, academics and students in lively discussions that informed his ongoing research in the cultural formations of theatre in Canada. -

Reference Guide This List Is for Your Reference Only

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA ACT OF THE HEART BLACKBIRD 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / 2012 / Director-Writer: Jason Buxton / 103 min / English / PG English / 14A A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a Sean (Connor Jessup), a socially isolated and bullied teenage charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest conductor goth, is falsely accused of plotting a school shooting and in her church choir. Starring Geneviève Bujold and Donald struggles against a justice system that is stacked against him. Sutherland. BLACK COP ADORATION ADORATION 2017 / Director-Writer: Cory Bowles / 91 min / English / 14A 2008 / Director-Writer: Atom Egoyan / 100 min / English / 14A A black police officer is pushed to the edge, taking his For his French assignment, a high school student weaves frustrations out on the privileged community he’s sworn to his family history into a news story involving terrorism and protect. The film won 10 awards at film festivals around the invites an Internet audience in on the resulting controversy. world, and the John Dunning Discovery Award at the CSAs. With Scott Speedman, Arsinée Khanjian and Rachel Blanchard. CAST NO SHADOW 2014 / Director: Christian Sparkes / Writer: Joel Thomas ANGELIQUE’S ISLE Hynes / 85 min / English / PG 2018 / Directors: Michelle Derosier (Anishinaabe), Marie- In rural Newfoundland, 13-year-old Jude Traynor (Percy BEEBA BOYS Hélène Cousineau / Writer: James R. -

Are We There Yet? Gay Representation in Contemporary Canadian Drama

Are We There Yet? Gay Representation in Contemporary Canadian Drama by T. Berto A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre Studies Guelph, Ontario, Canada © T. Berto, August, 2013 ABSTRACT ARE WE THERE YET? REPRESENTATIONS OF GAY MEN IN CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN THEATRE Tony Berto Advisor: University of Guelph, 2013 Professor Ann Wilson This study acknowledges that historical antipathies towards gay men have marginalised their theatrical representation in the past. However, over the last century a change has occurred in the social location of gay men in Canada (from being marginalised to being included). Given these changes, questions arise as to whether staged representations of gay men are still marginalised today. Given antipathies towards homosexuality and homophobia may contribute to the how theatres determine the riskiness of productions, my investigation sought a correlation between financial risk in theatrical production and the marginalisation of gay representations on stage. Furthermore, given that gay sex itself, and its representation on stage, have been theorised as loci of antipathies to gayness, I investigate the relationship between the visibility and overtness of gay sex in a given play and the production of that play’s proximity to the mainstream. The study located four plays from across the spectrum of production conditions (from high to low financial risk) in BC. Analysis of these four plays shows general trends, not only in the plays’ constructions but also in the material conditions of their productions that indicate that gay representations become more overt, visible and sexually explicit when less financial risk was at stake. -

LGBTQ+ - Relationships Eight Characters Four Male; Four Female Two Acts

Title: 2 Lives in - Selected Plays of Arthur Laurents - COL Author: Laurents, Arthur Publisher: Back Stage Books 2004 Description: roy drama - LGBTQ+ - relationships eight characters four male; four female two acts Matt Singer, a playwright and his long term partner Howard Thompson, a landscape gardener, are celebrating Howard's birthday. But tragedy strikes. Title: 2-2-Tango in - Making, Out / CCO Author: MacIvor, Daniel Publisher: Coach House Press 1992 Description: roy relationships - LGBTQ+ - men all male cast; two characters two male one act '. a highly stylized presentation that features clipped, overlapping dialogue and rigidly choreographed gestures. (MacIvor's) observations about the eternal struggle in relationships between emotional, physical and spiritual need and the assertions of independence easily exceed the gay context in which they are being played out.' Title: Abraham Lincoln's Big, Gay Dance Party Author: Loeb, Aaron Publisher: Playscripts, Inc. 2011 Description: roy comedy - prejudice - LGBTQ+ - homophobia - history nineteen characters four male; three female (doubling) three acts Illinois schoolteacher Harmony Green has told her fourth grade class that Menard County's most beloved homegrown hero, Abraham Lincoln, was gay. When Honest Abe is "outed" in a reimagined Christmas pageant, controversy and chaos engulf the town. As the trial of the century begins, big-city reporters and Congressional candidates descend, and family skeletons are forced out of the closet. Top hats and beards abound in this hilarious, poignant, and timely look at prejudice past and present. Title: Adam and the Experts Author: Bumbalo, Victor Publisher: Broadway Play Publishing 1990 Description: roy drama - AIDS - LGBTQ+ seven characters five male; two female two acts "ADAM AND THE EXPERTS .. -

Into the Forest

INTO THE FOREST WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY Patricia Rozema BASED ON THE NOVEL BY Jean Hegland a BRON STUDIOS and RHOMBUS MEDIA production in association with DAS FILMS, SELAVY, VIE ENTERTAINMENT and CW MEDIA FINANCE STARRING Ellen Page Evan Rachel Wood Max Minghella Callum Keith Rennie Wendy Crewson 101 MINUTES PR Contacts US Sara Serlen, ID PR E: [email protected] / P: 212.774.6148 / C: 917-239.0829 Canada Dana Fields, TARO PR E: [email protected] / P: 416.930.1075 / C: 416.930.1075 SYNOPSIS In the not-too-distant future, two ambitious young women, Nell and Eva, live with their father in a lovely but run-down home up in the mountains somewhere on the West Coast. Suddenly the power goes out; no one knows why. No electricity, no gasoline. Their solar power system isn’t working. Over the following days, the radio reports a thousand theories: technical breakdowns, terrorism, disease and uncontrolled violence across the continent. Then, one day, the radio stops broadcasting. Absolute silence. Step by ominous step, everything that Nell, a would-be academic, and Eva, a hard working contemporary dancer, have come to rely on is stripped away: parental protection, information, food, safety, friends, lovers, music -- all gone. They are faced with a world where rumor is the only guide, trust is a scarce commodity, gas is king and loneliness is excruciating. To battle starvation, invasion and despair, Nell and Eva fall deeper into a primitive life that tests their endurance and bond. Ultimately, the sisters must work together to survive and learn to discover what the earth will provide. -

Harold Award Houses

Harold Award Houses Barbara Fingerote Founders Paul Bettis Luter Hansraj Kirsten Johnson Sherrie Johnson Jacoba Knaapen Daniel MacIvor Don McKellar Darren O’Donnell Alex Poch-Golden Nadia Ross Lisa Ryder Sarah Stanley Deanne Taylor Ken McDougall Award Award 1995 Richard Feren Bianca Jacobs Peter Lynch Bob Wallace Leslie Lester David Duclos Sky Gilbert Asher Turin Robin Fulford Veronika Hurnik Josie Le Grice Eileen O’Toole Jim Jones 1996 Daniel Brooks Kim Roberts Richard Vaughan Gwen Bartleman Alisa Palmer Bryan James Hillar Liitoja The Founders Andrew Scorer Joey Meyer Ron Kennell Jim Warren Rose Jacobson Franco Boni 1997 Tracy Wright Ahdri Zhina Mandiela Jonathan DaSilva Fiona Jones Alex Bulmer Maxine Bailey Sigrid Johnson --- David Anderson Ruthe Whiston Maria Costa Leah Cherniak Lynda Hill Cathy Gordon in memory of Mark 1998 Clare Coulter M. Nourbese Philips Ed Roy Rex Buckle Eryn Dace Trudell Jean Yoon Rebecca Picherak Ida Carnevale Andrea Lundy David Baile Jennifer Brewin Viv Moore Michael Waller Shields 1999 Winston Morgan Diane Roberts Elley-Ray Hennessy Will Sutton Sharon Di Genova Marion de Vries Peter Freund Toronto Arts Council Arturo Fresolone Derek Bruce Sally Szuster --- Keith Cole Chris Abraham Marcus Magdalena & Christine Moynihan / Mira 2000 Sandra Hodnett Sally Han Roger West Jennifer Watkins Rose Stella Kimberly Purtell Michael Hollingsworth Peter Nikolic Natasha Parsons Wendy Krekeler Gregory Nixon Simon Heath Chris Prideaux Friedlander 2001 Nancy Webster Naomi Campbell Adrien Whan David Hoekstra Jane Marsland Daniel -

Wilby Wonderful

Wilby Wonderful A film by Daniel MacIvor Running Time: 99 min. Distributor Contact: Josh Levin Film Movement Series 109 W. 27th St., Suite 9B, New York, NY 10001 Tel: 212-941-7744 ext. 213 Fax: 212-941-7812 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Wilby Wonderful is a bittersweet comedy about the difference a day makes. Over the course of twenty-four hours, the residents of the tiny island town of Wilby try to maintain business as a sex scandal threatens to rock the town to its core. The town’s video store owner, Dan Jarvis (James Allodi) – depressed over the pending revelations about his love life – decides to end it all, but keeps getting interrupted by Duck MacDonald (Callum Keith Rennie), the town’s dyslexic sign-painter, during his half-hearted suicide attempts. Meanwhile, Dan has enlisted blindly ambitious real estate agent Carol French (Sandra Oh) to sell his house in an effort to quickly tie up the last of his loose ends. Carol, however, is more interested in selling her recently deceased mother-in-law’s house to Mayor Brent Fisher (Maury Chaykin), in order to get in with the in-crowd. To take her social step up, Carol could use the help of her police officer husband Buddy (Paul Gross), but Buddy has his hands full with sexy, wrong-side-of-the-tracks Sandra Anderson (Rebecca Jenkins), who can never decide if she is coming or going. Sandra’s daughter Emily (Ellen Page), is none too thrilled about her mother repeating her typical pattern of married men and bad reputation, but Emily herself is just about to have her heart broken for the very first time. -

Past Perfect Is a Romantic and Resonant First-Time Feature from Cape Breton Born Writer/Director Daniel Macivor

Mongrel Media Presents WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY DANIEL MACIVOR STARRING REBECCA JENKINS, DANIEL MACIVOR, MARIE BRASSARD, KATHRYN MACLELLAN AND MAURY CHAYKIN (Canada, 2002, 88 minutes) Distribution 109 Melville Ave. Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6G 1Y3 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] Past Perfect is a romantic and resonant first-time feature from Cape Breton born writer/director Daniel MacIvor. Produced by Camelia Frieberg with imX Communications’ Chris Zimmer acting as Executive Producer, Past Perfect was shot on location in Halifax. The film features Rebecca Jenkins (Black Harbor, South of Wawa, Bye Bye Blues), Maury Chaykin (Nero Wolfe, The Adjuster, The Sweet Hereafter), Marie Brassard (Polygraph, Le Confessional) and Daniel MacIvor (The Five Senses, Twitch City). Synopsis . .sometimes a destination can get in the way of a journey . Past Perfect takes place over two days, two years apart. On an overnight flight from Halifax to Vancouver, Charlotte (Rebecca Jenkins), an unemployed sales clerk on the verge of giving up on her dream of marriage and children, finds herself sitting next to the nervous and seemingly stuffy Cecil (Daniel MacIvor), a linguistics professor who is in the process of ending a long-term relationship with a woman (Marie Brassard) who does not share his desire for a family. Despite an unpleasant start to their relationship as seatmates, over the course of the flight Charlotte and Cecil find themselves falling into one another’s lives and in love.