Notion of 'Experience' in John Dewey's Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching for Apostasy: How Educational Methods and Philosophies Work Against the Church

The Lutheran Clarion – July 2018 (Volume 10, Issue 6) Teaching for Apostasy: How Educational Methods and Philosophies Work Against the Church Dr. Thomas Korcok gave the presentation below at the 2018 Lutheran Concerns Association conference in Fort Wayne, IN, in January 2018. Since that time it has been slightly revised. Currently in colleges of education across America, almost all future teachers learn from a standard canon of educational thinkers whose work forms the basis for the goals, methods, and structure of the modern American classroom. When students are introduced to these educationists, there is rarely, if ever, any consideration given to what they taught, believed, or confessed in their personal lives. Furthermore, their theories are presented as though they were all based purely on unbiased scientific research. Such an approach should be of concern for the Christian because it is radically different from how the church has traditionally measured teachers. In the history of Western education until the 20th century, (which has always been inseparably linked with Christian education), theology has been the measuring stick for all areas of knowledge, including education. A teacher’s confession of faith was always considered to be the first criterion in judging whether or not his or her teaching was acceptable. In the 16th century, the influential Lutheran educator, Valentin Trotzendorf, insisted that “Those who belong to our school, let the same also be members of our Church and those who agree with our faith, which is most sure and true; because of perhaps one godless person out of the whole body, some evil happens.” 1 In this day and age, we are to believe that the contrary teaching is true: that what a researcher teaches, believes, and confesses has little or nothing to do with the methods he advocates. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Introduction

1 Introduction Reading Democracy and Education DAVID T. HANSEN What is John Dewey’s Democracy and Education? In a literal sense, it is a study of education and its relation to the individual and society. More- over, Dewey tells us, it is a philosophical rather than historical, sociologi- cal, or political inquiry. His original title for the work was An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. That was the heading he had in view when he signed a contract to undertake the project on July 21, 1911, with the Macmillan Company of New York (MW.9.377). However, his publishers convinced him to change the title in light of pressing political issues triggered by the cataclysm of World War I. Dewey completed the text in August 1915, and it came out the following year with his original title converted into a subtitle. The book constitutes Dewey’s philosophical response to the rapid social, economic, political, cultural, and technologi- cal change he was witness to over the course of his long life. Born in 1859, when the United States was largely an agrarian society, by the time Dewey pens his educational treatise the country had become an indus- trial, urban world undergoing endless and often jarring transformations, a process that continues unabated through the present. Dewey sought to articulate and justify the education he believed people needed to com- prehend and shape creatively and humanely these unstoppable changes. At the same time, Dewey endeavored in the book to respond to what many critics regard as the two most influential educational works ever written prior to the twentieth century: Plato’s Republic (fourth 1 © 2006 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 John Dewey and Our Educational Prospect century B.C.E.) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile (published in 1762). -

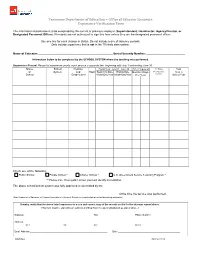

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Philosophical Foundations CEEF6301 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Christian Education Division Spring 2017 Online

Philosophical Foundations CEEF6301 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Christian Education Division Spring 2017 Online Emily Dean, Ph.D. Adjunct Professor, Christian Education Coordinator of Women’s Programs Office: (504) 282-4455 ext.8053 Email: [email protected] Mission Statement The mission of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary is to equip leaders to fulfill the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. Core Value Focus The seminary has five core values. 1. Doctrinal Integrity: Knowing that the Bible is the Word of God, we believe it, teach it, proclaim it, and submit to it. This course addresses Doctrinal Integrity specifically by preparing students to grow in understanding and interpreting of the Bible. 2. Spiritual Vitality: We are a worshiping community emphasizing both personal spirituality and gathering together as a Seminary family for the praise and adoration of God and instruction in His Word. Spiritual Vitality is addressed by reminding students that a dynamic relationship with God is vital for effective ministry. 3. Mission Focus: We are not here merely to get an education or to give one. We are here to change the world by fulfilling the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. This course addresses Mission Focus by helping students understand the biblical foundations for fulfilling the Great Commission and the Great Commandments. 4. Characteristic Excellence: What we do, we do to the utmost of our abilities and resources as a testimony to the glory of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Characteristic Excellence is addressed by preparing students to excel in their ability to interpret Scripture, which is foundational to effective ministry. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Peirce, Pragmatism, and the Right Way of Thinking

SANDIA REPORT SAND2011-5583 Unlimited Release Printed August 2011 Peirce, Pragmatism, and The Right Way of Thinking Philip L. Campbell Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-program laboratory managed and operated by Sandia Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lockheed Martin Corporation, for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000.. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily con- stitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. This report has been reproduced directly from the best available copy. -

Freewill and Determinism: the African Perspective and Experience

Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.2, pp.75-82, February 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) FREEWILL AND DETERMINISM: THE AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE AND EXPERIENCE Augustine Chidi Igbokwe, Department of Philosophy, Caritas University, Amorji – Nike P.M.B 01784, Enugu Enugu State – Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Whether Freewill and/or determinism has been an age long heated debate in the history of Western philosophy. The African metaphysical enquiry attempts a resolution by establishing a complementarity parlance between the two. Reality then becomes a paradox of harmony of opposites. In the midst of this harmony, a realization comes that the more a society turns modern, the more freedom is identified, subjecting deterministic tendencies to the periphery. As Africa is on the process to modernity, the system of communalism that had hitherto served Africa now gives way to individualism. In the same vein, there is need for a conscious change from unorganized but effective brotherhood to corporate and efficient governance to synergize this paradigm shift KEYWORDS: Freewill; Determinism; Communalism; Individualism; Free-Determinism. INTRODUCTION The philosophical argument on freewill and determinism which dates back to the ancient period still takes the front burner in our philosophical discourse today. How free are our actions and the choices we make? This question becomes pertinent when we juxtapose it with the long assumed assertion that every effect has a cause. If our actions as effects are all caused, then how morally responsible are we in our actions? This is usually the major paradox in the discourse on freewill and determinism and this is the major rationale behind the insistence on the heated debate. -

Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/10/2011, SPi 3 Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts Johannes Roessler On one view, an adequate account of causal understanding may focus exclusively on what is involved in mastering general causal concepts (concepts such as ‘x causes y’ or ‘p causally explains q’). An alternative view is that causal understanding is, partly but irreducibly, a matter of grasping what Anscombe called special causal concepts, con- cepts such as ‘push’, ‘flatten’,or‘knock over’. We can label these views generalist vs particularist approaches to causal understanding. It is worth emphasizing that the contrast here is not between two kinds of theories of the metaphysics of causation, but two views of the nature and perhaps source of ordinary causal understanding. One aim of this paper is to argue that it would be a mistake to dismiss particularism because of its putative metaphysical commitments. I begin by formulating an intuitively attractive version of particularism due to P.F. Strawson, a central element of which is what I will call na¨ıve realism concerning mechanical transactions. I will then present the account with two challenges. Both challenges reflect the worry that Strawson’s particularism may be unable to acknowledge the intimate connection between causa- tion and counterfactuals, as articulated by the interventionist approach to causation. My project will be to allay these concerns, or at least to explore how this might be done. My (tentative) conclusion will be that Strawson’sna¨ıve realism can accept what interventionism has to say about ordinary causal understanding, and that intervention- ism should not be seen as being committed to generalism. -

CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS, and MEANING Author(S): TYLER BURGE Source: Metaphilosophy, Vol

CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS, AND MEANING Author(s): TYLER BURGE Source: Metaphilosophy, Vol. 24, No. 4 (October 1993), pp. 309-325 Published by: Wiley Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24439033 Accessed: 11-04-2017 02:15 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24439033?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Wiley is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Metaphilosophy This content downloaded from 128.97.244.236 on Tue, 11 Apr 2017 02:15:14 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms © The Metaphilosophy Foundation and Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1993. Published by Blackwell Publishers, 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK and 238 Main Street, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA METAPHILOSOPHY Vol 24, No 4, October 1993 0026-1068 CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS, AND MEANING* ** TYLER BURGE The Aristotelian tradition produced many of the elements of what is widely thought of as "the traditional view" of concepts. I begin by attempting to summarize this view. The summary runs roughshod over numerous distinctions that were dear to various thinkers who contributed to this general conception of concepts. -

The Explanatory Role of the Notion of Representation

The Explanatory Role of the Notion of Representation Michael Strevens Draft of November 2004 ABSTRACT This paper investigates the explanatory role, in scientific theories, of the no- tion of representation and other kindred notions, such as the notions of in- formation and coding. I develop a simple account of the use of the notion of a representation, or more specifically the notion of an inner map, in a class of explanations of animals’ navigational capacities. I then show that the account, though simple, is more widely applicable than it seems, and I pose the question whether the same simple account could make sense of the use of representational notions in other kinds of scientific explanation, such as the explanations of neuroscience, genetics, developmental biology, cognitive psychology, and so on. I extend the account of the explanation of capacities to the explanation of behavior, and conclude by discussing representations of goals. 1 CONTENTS 1 Representations in Explanations 3 2 The R-C Model of Explanation 5 2.1 Explaining Navigational Capacities . 5 2.2 The Role of the Detection Mechanism: Establishing Covariation 8 2.3 The Role of the Prosecution Mechanism: Exploiting Covariation 10 2.4 The R-C Model . 11 3 Extending the R-C Model 13 3.1 Covariation and the Representation of Past and Future States of Affairs . 13 3.2 Representations of Permanent States of Affairs . 15 3.3 Complex Exploitation . 16 4 Beyond Navigation 19 4.1 Further Extending the R-C Model . 19 4.2 Other Animals, Other Capacities . 20 4.3 Other Kinds of Explananda .