Obstetrics and Gynecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Te2, Part Iii

TERMINOLOGIA EMBRYOLOGICA Second Edition International Embryological Terminology FIPAT The Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology A programme of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA) TE2, PART III Contents Caput V: Organogenesis Chapter 5: Organogenesis (continued) Systema respiratorium Respiratory system Systema urinarium Urinary system Systemata genitalia Genital systems Coeloma Coelom Glandulae endocrinae Endocrine glands Systema cardiovasculare Cardiovascular system Systema lymphoideum Lymphoid system Bibliographic Reference Citation: FIPAT. Terminologia Embryologica. 2nd ed. FIPAT.library.dal.ca. Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology, February 2017 Published pending approval by the General Assembly at the next Congress of IFAA (2019) Creative Commons License: The publication of Terminologia Embryologica is under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0) license The individual terms in this terminology are within the public domain. Statements about terms being part of this international standard terminology should use the above bibliographic reference to cite this terminology. The unaltered PDF files of this terminology may be freely copied and distributed by users. IFAA member societies are authorized to publish translations of this terminology. Authors of other works that might be considered derivative should write to the Chair of FIPAT for permission to publish a derivative work. Caput V: ORGANOGENESIS Chapter 5: ORGANOGENESIS -

Sexual Assault Cover

Sexual Assault Victimization Across the Life Span A Clinical Guide G.W. Medical Publishing, Inc. St. Louis Sexual Assault Victimization Across the Life Span A Clinical Guide Angelo P. Giardino, MD, PhD Associate Chair – Pediatrics Associate Physician-in-Chief St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children Associate Professor in Pediatrics Drexel University College of Medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Elizabeth M. Datner, MD Assistant Professor University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Department of Emergency Medicine Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine in Pediatrics Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Janice B. Asher, MD Assistant Clinical Professor Obstetrics and Gynecology University of Pennsylvania Medical Center Director Women’s Health Division of Student Health Service University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania G.W. Medical Publishing, Inc. St. Louis FOREWORD Sexual assault is broadly defined as unwanted sexual contact of any kind. Among the acts included are rape, incest, molestation, fondling or grabbing, and forced viewing of or involvement in pornography. Drug-facilitated behavior was recently added in response to the recognition that pharmacologic agents can be used to make the victim more malleable. When sexual activity occurs between a significantly older person and a child, it is referred to as molestation or child sexual abuse rather than sexual assault. In children, there is often a "grooming" period where the perpetrator gradually escalates the type of sexual contact with the child and often does not use the force implied in the term sexual assault. But it is assault, both physically and emotionally, whether the victim is a child, an adolescent, or an adult. The reported statistics are only an estimate of the problem’s scope, with the actual reporting rate a mere fraction of the true incidence. -

Female Infertility: Ultrasound and Hysterosalpoingography

s z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 11, Issue, 01, pp.745-754, January, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24941/ijcr.34061.01.2019 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE FEMALE INFERTILITY: ULTRASOUND AND HYSTEROSALPOINGOGRAPHY 1*Dr. Muna Mahmood Daood, 2Dr. Khawla Natheer Hameed Al Tawel and 3 Dr. Noor Al _Huda Abd Jarjees 1Radiologist Specialist, Ibin Al Atheer hospital, Mosul, Iraq 2Lecturer Radiologist Specialist, Institue of radiology, Mosul, Iraq 3Radiologist Specialist, Ibin Al Atheer Hospital, Mosu, Iraq ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The causes of female infertility are multifactorial and necessitate comprehensive evaluation including Received 09th October, 2018 physical examination, hormonal testing, and imaging. Given the associated psychological and Received in revised form th financial stress that imaging can cause, infertility patients benefit from a structured and streamlined 26 November, 2018 evaluation. The goal of such a work up is to evaluate the uterus, endometrium, and fallopian tubes for Accepted 04th December, 2018 anomalies or abnormalities potentially preventing normal conception. Published online 31st January, 2019 Key Words: WHO: World Health Organization, HSG, Hysterosalpingography, US: Ultrasound PID: pelvic Inflammatory Disease, IV: Intravenous. OHSS: Ovarian Hyper Stimulation Syndrome. Copyright © 2019, Muna Mahmood Daood et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Citation: Dr. Muna Mahmood Daood, Dr. Khawla Natheer Hameed Al Tawel and Dr. Noor Al _Huda Abd Jarjees. 2019. “Female infertility: ultrasound and hysterosalpoingography”, International Journal of Current Research, 11, (01), 745-754. -

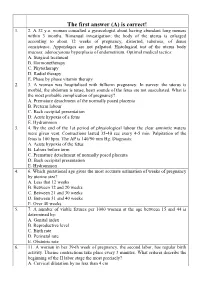

The First Answer (A) Is Correct! 1

The first answer (A) is correct! 1. 2. A 32 y.o. woman consulted a gynecologist about having abundant long menses within 3 months. Bimanual investigation: the body of the uterus is enlarged according to about 12 weeks of pregnancy, distorted, tuberous, of dense consistence. Appendages are not palpated. Histological test of the uterus body mucosa: adenocystous hyperplasia of endometrium. Optimal medical tactics: A. Surgical treatment B. Hormonetherapy C. Phytotherapy D. Radial therapy E. Phase by phase vitamin therapy 2. 3. A woman was hospitalised with fullterm pregnancy. In survey: the uterus is morbid, the abdomen is tense, heart sounds of the fetus are not auscultated. What is the most probable complication of pregnancy? A. Premature detachment of the normally posed placenta B. Preterm labour C. Back occipital presentation D. Acute hypoxia of a fetus E. Hydramnion 3. 4. By the end of the 1st period of physiological labour the clear amniotic waters were given vent. Contractions lasted 35-40 sec every 4-5 min. Palpitation of the fetus is 100 bpm. The AP is 140/90 mm Hg. Diagnosis: A. Acute hypoxia of the fetus B. Labors before term C. Premature detachment of normally posed placenta D. Back occipital presentation E. Hydramnion 4. 6. Which gestational age gives the most accurate estimation of weeks of pregnancy by uterine size? A. Less that 12 weeks B. Between 12 and 20 weeks C. Between 21 and 30 weeks D. Between 31 and 40 weeks E. Over 40 weeks 5. 7. A number of viable fetuses per 1000 women at the age between 15 and 44 is determined by: A. -

Topic N 26: Organization of the Gynecological Hospital. Research Methods in Gynecology. the Main Indicator of the Effectiveness

Таблица 1.Перечень заданий по гинекологии для студентов 5 курса лечебного факультета за VII – учебный семестр, обучающихся на английском языке. Topic N 26: Organization of the gynecological hospital. Type The code Research methods in gynecology. Ф The main indicator of the effectiveness of a preventive В 001 gynecological examination of working women is О Г number of women examined О Б the number of gynecological patients taken to the dispensary О В the number of women referred for treatment in a sanatorium the proportion of identified gynecological patients among the О А examined women О Д correct a) and б) The role of examination gynecological rooms in polyclinics В 002 consists, as a rule О Г in the medical examination of gynecological patients О Б in the examination and observation of pregnant women О В in conducting periodic medical examinations О А in coverage of preventive examinations of unemployed women О Д correct в) and г) Women's consultation is a structural unit 1) maternity hospital В 003 2) clinics 3) medical and sanitary part 4) sanatorium-preventorium О Б correct 1, 2, 3 О А correct 1, 2 О В all answers are correct О Г correct only 4 О Д all answers are wrong The concept of "family planning" most likely means activities that help families В 004 1) avoid unwanted pregnancy 2) adjust the intervals between pregnancies 3) to produce the desired children 4) increase the birth rate О А correct 1, 2, 3 О Б correct 1, 2 О В all answers are correct О Г correct only 4 О Д all answers are wrong In a women's consultation it is advisable -

New Insights Into Human Female Reproductive Tract Development

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works Title New insights into human female reproductive tract development. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7pm5800b Journal Differentiation; research in biological diversity, 97 ISSN 0301-4681 Authors Robboy, Stanley J Kurita, Takeshi Baskin, Laurence et al. Publication Date 2017-09-01 DOI 10.1016/j.diff.2017.08.002 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Differentiation 97 (2017) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Differentiation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/diff New insights into human female reproductive tract development MARK ⁎ Stanley J. Robboya, , Takeshi Kuritab, Laurence Baskinc, Gerald R. Cunhac a Department of Pathology, Duke University, Davison Building, Box 3712, Durham, NC 27710, United States b Department of Cancer Biology and Genetics, The Comprehensive Cancer Center, Ohio State University, 460 W. 12th Avenue, 812 Biomedical Research Tower, Columbus, OH 43210, United States c Department of Urology, University of California, 400 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94143, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: We present a detailed review of the embryonic and fetal development of the human female reproductive tract Human Müllerian duct utilizing specimens from the 5th through the 22nd gestational week. Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) as well as Urogenital sinus immunohistochemical stains were used to study the development of the human uterine tube, endometrium, Uterovaginal canal myometrium, uterine cervix and vagina. Our study revisits and updates the classical reports of Koff (1933) and Uterus Bulmer (1957) and presents new data on development of human vaginal epithelium. Koff proposed that the Cervix upper 4/5ths of the vagina is derived from Müllerian epithelium and the lower 1/5th derived from urogenital Vagina sinus epithelium, while Bulmer proposed that vaginal epithelium derives solely from urogenital sinus epithelium. -

Sl.No CGHS Treatment Procedure/Investigation List Rates for Non NABH Rates for NABH CGHS Bengaluru Rate List

CGHS Bengaluru Rate List Sl.No CGHS Treatment Procedure/Investigation Rates for Non Rates for List NABH NABH 1 Consultation OPD 135 135 2 Consultation- for Inpatients 270 270 3 Dressings of wounds 45 52 4 Suturing of wounds with local anesthesia 108 124 5 Aspiration Plural Effusion - Diagnostic 120 138 6 Aspiration Plural Effusion - Therapeutic 174 200 7 Abdominal Aspiration - Diagnostic 330 380 8 Abdominal Aspiration - Therapeutic 414 476 9 Pericardial Aspiration 342 393 10 Joints Aspiration 285 329 11 Biopsy Skin 207 239 12 Removal of Stitches 36 41 13 Venesection 124 143 14 Phimosis Under LA 1180 1357 15 Sternal puncture 173 199 16 Injection for Haemorrhoids 373 428 17 Injection for Varicose Veins 315 363 18 Catheterisation 425 500 19 Dilatation of Urethra 450 518 20 Incision & Drainage 378 435 21 Intercostal Drainage 125 144 22 Peritoneal Dialysis 1319 1517 TREATMENT PROCEDURE SKIN 23 Excision of Moles 311 357 24 Excision of Warts 279 321 25 Excision of Molluscum contagiosum 117 135 26 Excision of Veneral Warts 144 166 27 Excision of Corns 126 145 28 I/D Injection Keloid 97 112 29 Chemical Cautery (s) 99 114 TREATMENT PROCEDURE OPTHALMOLOGY 30 66 76 eyes Subconjunctival/subtenon’s injections in one 31 132 152 eyes 32 PterygiumSubconjunctival/subtenon’s Surgery injections in both 5550 6325 33 Conjunctival Peritomy 58 67 34 Conjunctival wound repair or exploration 3300 3795 following blunt trauma 35 Removal of corneal foreign body 115 132 36 Cauterization of ulcer/subconjunctival injection 69 79 in one eye 37 Cauterization of ulcer/subconjunctival -

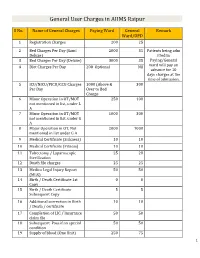

General User Charges in AIIMS Raipur

General User Charges in AIIMS Raipur S No. Name of General Charges Paying Ward General Remark Ward/OPD 1 Registration Charges 200 25 2 Bed Charges Per Day (Sami 2000 35 Patients being adm Deluxe) itted in 3 Bed Charges Per Day (Deluxe) 3000 35 Paying/General 4 Diet Charges Per Day 200 Optional Nil ward will pay an advance for 10 days charges at the time of admission. 5 ICU/NICU/PICU/CCU Charges 1000 (Above & 300 Per Day Over to Bed Charge 6 Minor Operation in OT/MOT 250 100 not mentioned in list, under L A 7 Minor Operation in OT/MOT 1000 300 not mentioned in list, under G A 8 Major Operation in OT, Not 2000 1000 mentioned in list under G A 9 Medical Certificate (Sickness) 10 10 10 Medical Certificate (Fitness) 10 10 11 Tubectomy / Laparoscopic 25 20 Sterilization 12 Death file charges 25 25 13 Medico Legal Injury Report 50 50 (MLR) 14 Birth / Death Certificate 1st 0 0 Copy 15 Birth / Death Certificate 5 5 Subsequent Copy 16 Additional correction in Birth 10 10 / Death / certificate 17 Completion of LIC / Insurance 50 50 claim file 18 Subsequent Pass if on special 50 50 condition 19 Supply of blood (One Unit) 250 75 1 20 Medical Board Certificate 500 500 On Special Case User Charges for Investigations in AIIMS Raipur S No. Name of Investigations Paying General Remark Ward Ward/OPD Anaesthsia 1 ABG 75 50 2 ABG ALONGWITH 150 100 ELECTROLYTES(NA+,K+)(Na,K) 3 ONLY ELECTROLYTES(Na+,K+,Cl,Ca+) 75 50 4 ONLY CALCIUM 50 25 5 GLUCOSE 25 20 6 LACTATE 25 20 7 UREA. -

Cervical Ectropion May Be a Cause of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis. Leia Mitchell

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University Health Sciences Research Commons Obstetrics and Gynecology Faculty Publications Obstetrics and Gynecology 4-28-2017 Cervical Ectropion May Be a Cause of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis. Leia Mitchell Michelle King Heather Brillhart George Washington University Andrew Goldstein Follow this and additional works at: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/smhs_obgyn_facpubs Part of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons APA Citation Mitchell, L., King, M., Brillhart, H., & Goldstein, A. (2017). Cervical Ectropion May Be a Cause of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis.. Sexual Medicine, (). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2017.03.001 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Obstetrics and Gynecology at Health Sciences Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Obstetrics and Gynecology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Health Sciences Research Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cervical Ectropion May Be a Cause of Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis Leia Mitchell, MSc,1 Michelle King, MSc,1,2 Heather Brillhart, MD,3 and Andrew Goldstein, MD1,3 ABSTRACT Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is a poorly understood chronic vaginitis with an unknown etiology. Symptoms of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis include copious yellowish discharge, vulvovaginal discomfort, and dyspareunia. Cervical ectropion, the presence of glandular columnar cells on the ectocervix, has not been reported as a cause of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. Although cervical ectropion can be a normal clinical finding, it has been reported to cause leukorrhea, metrorrhagia, dyspareunia, and vulvovaginal irritation. Patients with cervical ectropion and des- quamative inflammatory vaginitis are frequently misdiagnosed with candidiasis or bacterial vaginosis and repeatedly treated without resolution of symptoms. -

History of Morgellons Disease: from Delusion to Definition

Journal name: Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology Article Designation: REVIEW Year: 2018 Volume: 11 Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology Dovepress Running head verso: Middelveen et al Running head recto: Morgellons disease open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S152343 Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW History of Morgellons disease: from delusion to definition Marianne J Middelveen1 Abstract: Morgellons disease (MD) is a skin condition characterized by the presence of Melissa C Fesler2 multicolored filaments that lie under, are embedded in, or project from skin. Although the Raphael B Stricker2 condition may have a longer history, disease matching the above description was first reported in the US in 2002. Since that time, the condition that we know as MD has become a polemic 1Atkins Veterinary Services, Calgary, AB, Canada; 2Union Square Medical topic. Because individuals afflicted with the disease may have crawling or stinging sensations Associates, San Francisco, CA, USA and sometimes believe they have an insect or parasite infestation, most medical practitioners consider MD a purely delusional disorder. Clinical studies supporting the hypothesis that MD is exclusively delusional in origin have considerable methodological flaws and often neglect the fact that mental disorders can result from underlying somatic illness. In contrast, rigorous experimental investigations show that this skin affliction results from a physiological response to the presence of an infectious agent. Recent studies from that point of view show an association between MD and spirochetal infection in humans, cattle, and dogs. These investigations have Video abstract determined that the cutaneous filaments are not implanted textile fibers, but are composed of the cellular proteins keratin and collagen and result from overproduction of these filaments in response to spirochetal infection. -

Management of Reproductive Tract Anomalies

The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India (May–June 2017) 67(3):162–167 DOI 10.1007/s13224-017-1001-8 INVITED MINI REVIEW Management of Reproductive Tract Anomalies 1 1 Garima Kachhawa • Alka Kriplani Received: 29 March 2017 / Accepted: 21 April 2017 / Published online: 2 May 2017 Ó Federation of Obstetric & Gynecological Societies of India 2017 About the Author Dr. Garima Kachhawa is a consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist in Delhi since over 15 years; at present, she is working as faculty at the premiere institute of India, prestigious All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. She has several publications in various national and international journals to her credit. She has been awarded various national awards, including Dr. Siuli Rudra Sinha Prize by FOGSI and AV Gandhi award for best research in endocrinology. Her field of interest is endoscopy and reproductive and adolescent endocrinology. She has served as the Joint Secretary of FOGSI in 2016–2017. Abstract Reproductive tract malformations are rare in problems depend on the anatomic distortions, which may general population but are commonly encountered in range from congenital absence of the vagina to complex women with infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss. defects in the lateral and vertical fusion of the Mu¨llerian Obstructive anomalies present around menarche causing duct system. Identification of symptoms and timely diag- extreme pain and adversely affecting the life of the young nosis are an important key to the management of these women. The clinical signs, symptoms and reproductive defects. Although MRI being gold standard in delineating uterine anatomy, recent advances in imaging technology, specifically 3-dimensional ultrasound, achieve accurate Dr. -

Imperforate Anus and Cloacal Malformations Marc A

C H A P T E R 3 5 Imperforate Anus and Cloacal Malformations Marc A. Levitt • Alberto Peña ‘Imperforate anus’ has been a well-known condition since component but were left with a persistent urogenital antiquity.1–3 For many centuries, physicians, as well as sinus.21,23 Additionally, most rectovestibular fistulas were individuals who practiced medicine, have tried to help erroneously called ‘rectovaginal fistula’.21 A rectoblad- these children by creating an orifice in the perineum. derneck fistula in males is the only true supralevator Many patients survived, most likely because they suffered malformation and occurs in about 10%.18 As it is the only from a type of defect that is now recognized as ‘low.’ malformation in males in which the rectum is unreach- Those with a ‘high’ defect did not survive. In 1835, able through a posterior sagittal incision, it requires an Amussat was the first to suture the rectal wall to the skin abdominal approach (via laparoscopy or a laparotomy) in edges which was the first actual anoplasty.2 Stephens addition to the perineal approach. made a significant contribution by performing the first Anorectal malformations represent a wide spectrum of anatomic studies in human specimens. In 1953, he pro- defects. The terms ‘low,’ ‘intermediate,’ and ‘high’ are arbi- posed an initial sacral approach followed by an abdomi- trary and not useful in current therapeutic or prognostic noperineal operation, if needed.4 The purpose of the terminology. A therapeutic and prognostically oriented sacral stage of this procedure was to preserve the pub- classification is depicted in Box 35-1.24 orectalis sling, considered a key factor in maintaining fecal incontinence.