Singita Sabi Sand Wildlife Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation

conservation In pursuit of our 100 year purpose our commitment to conservation 25 years ago, on a piece of family-owned land in South Africa’s Sabi Sand Game Reserve, a boutique safari lodge opened on the banks of the Sand River, setting the pace for a new brand of luxury safari experiences. Singita Ebony Lodge would become the first of 12 environmentally sensitive properties dotted across Africa, forming the heartbeat of Singita’s conservation vision. The lodge created a benchmark for sustainable and eco-friendly tourism that remains to this day; a model which combines hospitality with an amazing wilderness experience to support the conservation of natural ecosystems. This founding philosophy drives every aspect of Singita’s day-to-day operations, as well as its vision for the future, which extends to the next 100 years and beyond. A single-minded purpose to preserve and protect large areas of African wilderness for future generations is the force behind an ambitious expansion strategy that will see Singita broaden its efforts to safeguard the continent’s most vulnerable species and their natural habitats in the coming years. The profound impact of Singita’s conservation work can be seen in the transformation of the land under its care, the thriving biodiversity of each reserve and concession, and the exceptional safari experience this affords our guests. With our lodges and camps across three countries partially funding the conservation of large areas of protected land, Singita has redefined luxury safaris as an essential tool for conservation contents Sustainability – operating in an environmentally conscious way at every level of the business – is a key component of conservation success, alongside maintaining the integrity of our reserves and their ecosystems, and working with local communities to ensure that they not only benefit from the existence of the lodges, but thrive because of them. -

Lion-Sands-Game-Reserve-Travel-Options-Fact-Sheet-2019.Pdf

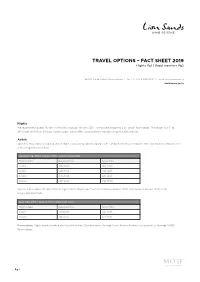

TRAVEL OPTIONS – FACT SHEET 2019 Flights Pg1 | Road Transfers Pg2 MORE Head Office/Reservations | Tel: +27 (0) 11 880 9992 | Email: [email protected] www.more.co.za Flights We recommend guests fly with Airlink into Skukuza Airport (SZK) – the closest airport to Lion Sands’ four lodges. The airport is a 5- to 25-minute drive from the Lion Sands lodges, which offer complimentary transfers in open safari vehicles. Airlink Operates twice-daily scheduled, direct flights connecting Johannesburg’s O.R. Tambo International Airport (JNB) and Skukuza Airport (SZK) in the Kruger National Park. Johannesburg (JNB) / Skukuza (SZK) / Johannesburg (JNB) Flight Number Departure Time Arrival Time SA8861 JNB 10h00 SZK 10h50 SA8862 SZK 13h30 JNB 14h35 SA8865 JNB 13h20 SZK 14h10 SA8866 SZK 14h50 JNB 15h50 Operates once-daily scheduled direct flights connecting Cape Town International Airport (CPT) and Skukuza Airport (SZK) in the Kruger National Park. Cape Town (CPT) / Skukuza (SZK) / Cape Town (CPT) Flight Number Departure Time Arrival Time SA8651 CPT 10h35 SZK 13h05 SA8652 SZK 11h20 CPT 13h55 Reservations: flights can be booked directly with Airlink (flyairlink.com), through South African Airways (flysaa.com), or through MORE Reservations. Pg 1 Unique Air Operates a Safari Link scheduled air-transfer service connecting lodges in Sabi Sand Game Reserve, Madikwe Game Reserve, Marataba South Africa, and Welgevonden Game Reserve on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Sabi Sand and Madikwe Departure Lodge Departure Time Arrival Lodge Arrival Time Sabi Sand 11h00 -

(Harry) Kirkman Was Born in the Steytlerville District of the Eastern Cape on 31St March 1899. He Il

Harry Kirkman Walter Henry (Harry) Kirkman was born in the Steytlerville District of the Eastern Cape on 31 st March 1899. He illegitimately joined up with the armed forces at the age of 15 and served in the East African campaign. After the war he took over the management of the T.C.L. cattle Ranch on the Sabie River (now the Sabi-Sand Game Reserve). He took over duties in 1927 from his friend Bert Tomlinson who left this position to become a Ranger in the Kruger National Park. Many of the duties of this position such as predator control, fire management and anti-poaching, were similar to those of a Ranger and in 1933 he followed his friend Bert Tomlinson into service with National Parks. Initially Col. James Stevenson-Hamilton in a clerical position, which was not much to his liking, employed him but he accepted the job as it gave him a foot in National Parks. In 1935 he was appointed to a Ranger’s position and was given the Sabi Section of the Park. Given his new status, he promptly married Ruby Cass. During this time, Harry followed up on reports of Black Rhino in the Gommondwane area of the KNP and found tracks, but could not get to see this animal. He was thus the last person to record this species in KNP as thereafter Black rhinos were not recorded again as they had become extinct. In 1938 Harry was moved to a new Ranger’s Section. This became known as Shangoni and he was instrumental in its development. -

The Sabi Sand Game Reserve an Exclusive Safari Haven

DISCOVER The Sabi Sand Game Reserve An exclusive safari haven The Sabi Sand Game Reserve is one of the most prestigious private game reserves in South Africa, and is famous for its incredible leopard sightings. The reserve shares an unfenced boundary with the 2 million hectare Kruger National Park, and is home to one of the richest wildlife populations in the country. &BEYOND SOUTH AFRICA DISCOVER THE SABI SAND GAME RESERVE Why visit the Adjacent to the world renowned Kruger National Park, the Sabi Sand Game Reserve is not only famed for its intimate wildlife encounters, Sabi Sand? but also for its elite luxurious lodges and exclusive experiences. 2 4 ICONIC WILDLIFE EXCLUSIVE PROPERTY In addition to incredible leopard &Beyond has exclusive traversing 1 viewing, and the famous Big Five, rights on 10,500 hectares PRISTINE LOCATION discover a vast variety of plant and (26,000 acre) of wilderness land, Sharing an unfenced border with the animal species that share 2 million 3 which means our guests can world renowned Kruger National Park, hectares of unfenced terrain with the FINEST GUIDES AND SAFARIS explore the reserve on foot, free the Sabi Sand Game Reserve is famed Kruger National Park. Encounter a Highly knowledgeable &Beyond- from the constraints of roads and for its intimate wildlife encounters, few of the over 500 bird species, trained guides can offer you vehicles, go on a night drive, or particularly leopard viewing and 145 animal species, 110 reptile night drives as well as specialist sensitively go off-road enabling the Big Five. The uniqueness of species and 45 fish species, that safaris such as walking, tracking, you to get closer to wildlife. -

WILDLIFE JOURNAL SINGITA SABI SAND, SOUTH AFRICA for the Month of October, Two Thousand and Nineteen

WILDLIFE JOURNAL SINGITA SABI SAND, SOUTH AFRICA For the month of October, Two Thousand and Nineteen Temperature Rainfall Recorded Sunrise & Sunset Average minimum: 19.3˚C (66.74˚F) For the month: 9.3mm Sunrise: 05:21 Average maximum: 33.5˚C (92.3˚F) For the season to date: 21.6mm Sunset: 18:01 Minimum recorded: 12˚C (53.6˚F) Maximum recorded: 42˚C (107.6˚F) Our senses tingle as the tenth month of the year commences. With the first rains for the summer season revitalising the dry dusty land, some of the smaller creatures are prompted into action. The loud raucous calls from frogs and toads accompanied by the chirping of European bee-eaters are a welcomed addition to the bushveld orchestra. With the Sand River almost completely dried up, we’ve witnessed an array of storks dominating the miniature pools, lapping up the opportunity to catch an easy meal. Predators such as leopards and lions have also been seen utilising the riverine area, hoping to catch an unsuspecting impala or nyala. The expression “keep your friends close, your enemies closer” could not be truer right now. Here’s a Sightings Snapshot for October: Lions • Many water sources have now dried up, including a large part of the Sand River. The sound of water flowing is minimal and the pools and dams of valuable water sources have become invaluable. We’ve watched predators such as lions taking full advantage of these places. The Ottawa pride in particular have used the shade of the reeds and bushwillows to lie in during the day, waiting for the inevitable arrival of water dependant antelope and buffalo to arrive. -

South Africa

Africa KIRKMAN’S KAMP Sabi Sand Game Reserve SOUTH AFRICA Adjacent to the world renowned Kruger National Park, the Sabi Sand Game Reserve is famed for its intimate wildlife encounters, particularly leopard viewing. Home to a host of animals, including the Big Five (lion, leopard, elephant, buffalo and rhino), the Sabi Sand is part of a conservation area that covers over two million hectares (almost five million acres), an area equivalent to the state of New Jersey. With no boundary fences Game drives traverse an between the Sabi Sand and area of 10 500 hectares the Kruger National Park, this (26 000 acres) and strict reserve benefits from the great vehicle limits at sightings diversity of animals found in ensure the exclusivity of the one of the richest wildlife areas game viewing experience. on the African continent, along Sensitive off-road driving with the additional benefits ensures that guests have the experienced on a private best possible view of any game reserve. exceptional sighting and rangers are constantly in touch with each other to keep track of animal movements. {Kirkman’s Kamp} www.andBeyond.com The spirit of safari comes alive at WHAT SETS US APART GUEST SAFETY “We LOVE, LOVE, LOVED historic &Beyond Kirkman’s Kamp. Kirkman’s Kamp! The safari itself Step back in time into the gracious • Gracious and genteel lodge The camp is not fenced off and exceeded our expectations! The early Transvaal atmosphere of this imbued with the history of Harry we request guests be extremely original 1920s homestead and Kirkman vigilant at all times. -

Andbeyond-Tengile-River-Lodge-1

SELF DRIVE DIRECTIONS Tengile River Lodge Reservations: +27 11 809 4300 | Emergency Tel: +27 83 463 8923 | Lodge Tel: + 27 13 591 1772 RECOMMENDED ROUTE TO &BEYOND TENGILE RIVER LODGE FROM JOHANNESBURG TO TENGILE RIVER LODGE Take the N12 (which turns into the N4) from Johannesburg to Nelspruit (Mbombela). A ring road has been built around Nelspruit (Mbombela), so that you do not need to drive through the town. When you reach Nelspruit (Mbombela), carry on along the N4, following the signs for Malelane and the Lebombo border post, and bypass the turnoff for the city centre. Once you have passed the bridge, take the slip road for the R40 to White River. Please be careful, as this road is only signposted once. Turn right at the bottom of the offramp. At the turning circle, take the road that is marked White River to your left. Turn left at the second set of traffic lights. This will take you onto the main road heading out of Nelspruit (the R40). Follow the R40 towards White River. As you approach White River, continue straight at the traffic circle and do not turn right. Once you have reached White River, the R40 will become the R538. Continue straight and cross over Danie Joubert Street, then turn left onto the R538 (Theo Kleyhans Street). When you reach the turning circle on the hill near the Casterbridge Centre, you will see that the road is marked Hazyview in both directions. Turn left onto the R40 once again. Continue straight into town and turn left when you reach the T-junction, following the sign towards Hazyview. -

INY Website Fact Sheet

Your reservation will be secured once you have received our with small children. *Please note that children travelling to the acknowledgement of payment. Republic of South Africa require additional documentation as All bank charges are the responsibility of the guest / travel stipulated by the Department of Home Affairs. company making the relevant bank transfer into the Inyati Game Lodge bank account. WHAT YOU CAN EXPECT TO FIND AT INYATI ACCOMMODATION TARIFFS QUOTED Inyati consists of eleven chalets. Each air-conditioned chalet The rates quoted are per person, per night sharing and priced features en-suite bathroom with twin hand basins, separate in South African Rand. They include accommodation as bath, shower and w.c. Accommodating 25 guests in total. detailed below & 15% VAT. Fact Sheet TARIFFS INCLUDE FACILITIES & ACTIVITIES Set on the lush banks of the Sand River, Inyati Game Air-conditioned en-suite accommodation, meals, tea & coffee. Curio shop Lodge offers the ultimate safari experience Game drives in open 4-wheel drive safari vehicles conducted A range of local and other African curios and crafts are combining diverse wildlife with authentic African by experienced guides and trackers, refreshment on game available for purchase in our curio shop. Where possible, we hospitality. From the warm welcome you receive upon drives, fishing, walking and spotlit night safaris. WiFi. source products locally to help support and develop our arrival, to our comfortable chalets, hearty home style cuisine Transfers to and from Ulusaba airstrip. communities. and highly experienced guides, every guest departs TARIFFS EXCLUDE Conference Applicable airport taxes, bar purchases, certain special meal Inyati has the ideal conference venue called Tree Tops with unforgettable memories and the imprint of Africa in requests, curio shop purchases, flights and transfers, gratuities, because of its setting in the tops of the tree’s on the banks of their soul. -

Itinerary for Sabi Sand Safari & Table Mountain

ITINERARY FOR SABI SAND SAFARI & TABLE MOUNTAIN TOUR - DELUXE - 2019 South Africa Let your imagination soar Journey overview Combine exceptional game viewing in one of South Africa’s best known game reserves with the scenic beauty of laid-back Cape Town. Enjoy intimate encounters with the famous Big Five in the renowned Sabi Sand Game Reserve, famous for its exceptional sightings of the magnificent leopard. Get to know the steady rhythm of the African bush before moving on to beautiful Cape Town. Relax on the city’s golden beaches, discover mementoes of its colourful past and immerse yourself in its vibrant culture or choose to visit the scenic Cape Winelands, where you can sample some of the world’s best wines. HIGHLIGHTS OF THE ITINERARY � Exceptional Big Five game viewing, including exceptional chances of leopard encounters, in the Sabi Sand Game Reserve � An opportunity to explore the cosmopolitan beauty of scenic Cape Town, set in the shadow of Table Mountain � Nature meets luxury MAKE THE MOST OF YOUR ADVENTURE � Learn the intimate details of the bush on a walking adventure � Take a helicopter-ride to the breathtaking Cape Winelands � Visit the penguins at Boulders Beach SPECIALLY CREATED FOR � First time African travelers � Food and wine lovers � Anyone starved for relaxation www.andBeyond.com Sabi Sand Safari & Table Mountain Tour (Deluxe) 2019 Rack - 2019-08-05 At a glance 8 nights / 9 days 2 Guests DAY PROGRAMME Day 1 � Connection flight assistance at OR Tambo International Airport � Scheduled flight from OR Tambo International -

The Sabi Sand Game Reserve an Exclusive Safari Haven

DISCOVER The Sabi Sand Game Reserve An exclusive safari haven The Sabi Sand Game Reserve is one of the most prestigious private game reserves in South Africa, and is famous for its incredible leopard sightings. The reserve shares an unfenced boundary with the 2 million hectare Kruger National Park, and is home to one of the richest wildlife populations in the country. &BEYOND SOUTH AFRICA DISCOVER THE SABI SAND GAME RESERVE Why visit the Adjacent to the world renowned Kruger National Park, the Sabi Sand Game Reserve is not only famed for its intimate wildlife encounters, Sabi Sand? but also for its elite luxurious lodges and exclusive experiences. 2 4 ICONIC WILDLIFE EXCLUSIVE PROPERTY In addition to incredible leopard &Beyond has exclusive traversing 1 viewing, and the famous Big Five, rights on 10,500 hectares PRISTINE LOCATION discover a vast variety of plant and (26,000 acre) of wilderness land, Sharing an unfenced border with the animal species that share 2 million 3 which means our guests can world renowned Kruger National Park, hectares of unfenced terrain with the FINEST GUIDES AND SAFARIS explore the reserve on foot, free the Sabi Sand Game Reserve is famed Kruger National Park. Encounter a Highly knowledgeable &Beyond- from the constraints of roads and for its intimate wildlife encounters, few of the over 500 bird species, trained guides can offer you vehicles, go on a night drive, or particularly leopard viewing and 145 animal species, 110 reptile night drives as well as specialist sensitively go off-road enabling the Big Five. The uniqueness of species and 45 fish species, that safaris such as walking, tracking, you to get closer to wildlife. -

South Africa - Just Cats!

South Africa - Just Cats! Naturetrek Tour Report 2 - 13 November 2009 Report compiled by Leon Marais Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report South Africa - Just Cats! Tour Leaders: Leon Marais John Davies Participants: Mick Tilley Christine Tilley David Revis Jan Revis Barbara Griffiths Sheila Hunt Susan Jenkins Judy Scott Day 0 Monday 2nd November Travel from the UK Day 1 Tuesday 3rd November The Blyde River Canyon The group arrived in cool and cloudy conditions in Johannesburg, and soon we were on our way eastwards towards the Blyde River Canyon, a five to six hour journey through the coal, maize and stock farming regions of western Mpumalanga and the highlands of the escarpment. We had a lunch stop in the small town of Graskop and then continued on to the Blyde River Canyon. After a rest period we headed up to the resort’s view site, where we at least had some views of the Three Rondavels and the lower end of the canyon, although the overcast conditions did not bring out the best in the scenery. We then headed back to our rooms and had time to freshen up before dinner in the resort’s Kadisi Restaurant, where we had a great dinner before calling it a day. Day 2 Wednesday 4th November Skukuza Rest Camp, KNP. After a morning birding walk at Blyde, under cool misty conditions, we had breakfast, packed and departed at 9 AM. -

Singita-Conservation-Brochure.Pdf

our commitment to conservation 25 years ago, on a piece of family-owned land in South Africa’s Sabi Sand Game Reserve, a boutique safari lodge opened on the banks of the Sand River, setting the pace for a new brand of luxury safari experiences. Singita Ebony Lodge would become the first of 12 environmentally sensitive properties dotted across Africa, forming the heartbeat of Singita’s conservation vision. The lodge created a benchmark for sustainable and eco-friendly tourism that remains to this day; a model which combines hospitality with an amazing wilderness experience to support the conservation of natural ecosystems. This founding philosophy drives every aspect of Singita’s day-to-day operations, as well as its vision for the future, which extends to the next 100 years and beyond. A single-minded purpose to preserve and protect large areas of African wilderness for future generations is the force behind an ambitious expansion strategy that will see Singita broaden its efforts to safeguard the continent’s most vulnerable species and their natural habitats in the coming years. The profound impact of Singita’s conservation work can be seen in the transformation of the land under its care, the thriving biodiversity of each reserve and concession, and the exceptional safari experience this affords our guests. With our lodges and camps across three countries partially funding the conservation of large areas of protected land, Singita has redefined luxury safaris as an essential tool for conservation contents Sustainability – operating in an environmentally conscious way at every level of the business – is a key component of conservation success, alongside maintaining the integrity of our reserves and their ecosystems, and working with local communities to ensure that they not only benefit from the existence of the lodges, but thrive because of them.