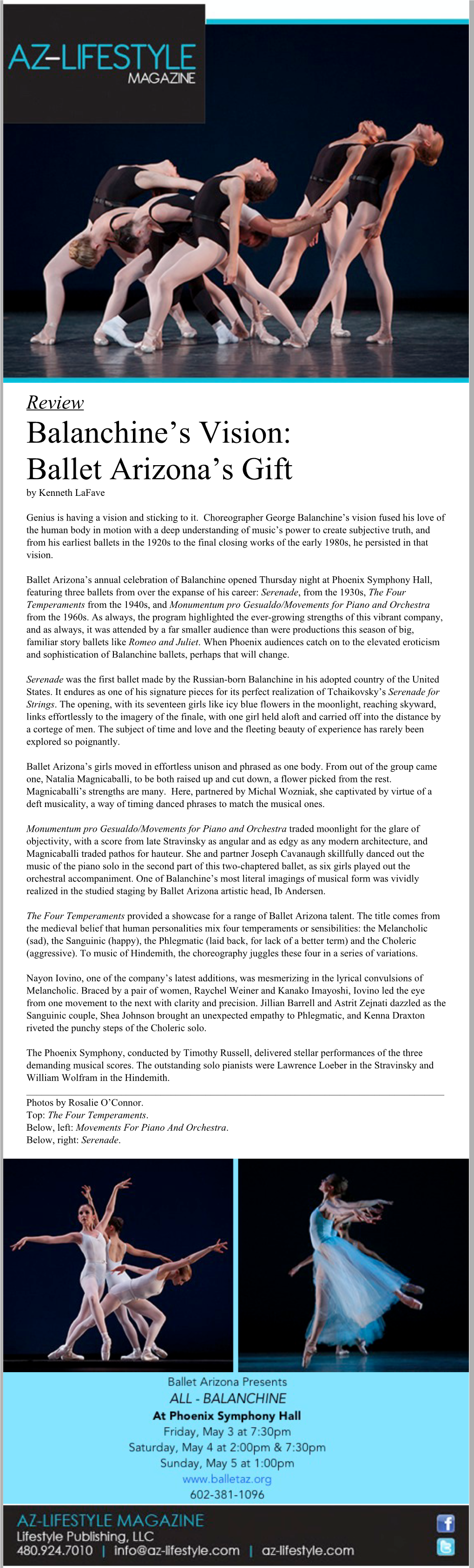

Balanchine's Vision: Ballet Arizona's Gift

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atheneum Nantucket Dance Festival

NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTIVAL 2011 Featuring stars of New York City Ballet & Paris Opera Ballet Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Dorothée Gilbert Teresa Reichlen Amar Ramasar Sterling Hyltin Tyler Angle Daniel Ulbricht Maria Kowroski Alessio Carbone Ana Sofia Scheller Sean Suozzi Chase Finlay Georgina Pazcoguin Ashley Laracey Justin Peck Troy Schumacher Musicians Cenovia Cummins Katy Luo Gillian Gallagher Naho Tsutsui Parrini Maria Bella Jeffers Brooke Quiggins Saulnier Cover: Photo of Benjamin Millepied by Paul Kolnik 1 Welcometo the Nantucket Atheneum Dance Festival! For 177 years the Nantucket Atheneum has enriched our island community through top quality library services and programs. This year the library served more than 200,000 adults, teens and children year round with free access to over 1.4 million books, CDs, and DVDs, reference and information services and a wide range of cultural and educational programs. In keeping with its long-standing tradition of educational and cultural programming, the Nantucket Atheneum is very excited to present a multifaceted dance experience on Nantucket for the fourth straight summer. This year’s performances feature the world’s best dancers from New York City Ballet and Paris Opera Ballet under the brilliant artistic direction of Benjamin Millepied. In addition to live music for two of the pieces in the program, this year’s program includes an exciting world premier by Justin Peck of the New York City Ballet. The festival this week has offered a sparkling array of free community events including two dance-related book author/illustrator talks, Frederick Wiseman’s film La Danse, Children’s Workshop, Lecture Demonstration and two youth master dance classes. -

Convert Finding Aid To

Fred Fehl: A Preliminary Inventory of His Dance Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Fehl, Fred, 1906-1995 Title: Fred Fehl Dance Collection 1940-1985 Dates: 1940-1985 Extent: 122 document boxes, 19 oversize boxes, 3 oversize folders (osf) (74.8 linear feet) Abstract: This collection consists of photographs, programs, and published materials related to Fehl's work documenting dance performances, mainly in New York City. The majority of the photographs are black and white 5 x 7" prints. The American Ballet Theatre, the Joffrey Ballet, and the New York City Ballet are well represented. There are also published materials that represent Fehl's dance photography as reproduced in newspapers, magazines and other media. Call Number: Performing Arts Collection PA-00030 Note: This brief collection description is a preliminary inventory. The collection is not fully processed or cataloged; no biographical sketch, descriptions of series, or indexes are available in this inventory. Access: Open for research. An advance appointment is required to view photographic negatives in the Reading Room. For selected dance companies, digital images with detailed item-level descriptions are available on the Ransom Center's Digital Collections website. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases and gift, 1980-1990 (R8923, G2125, R10965) Processed by: Sue Gertson, 2001; Helen Adair and Katie Causier, 2006; Daniela Lozano, 2012; Chelsea Weathers and Helen Baer, 2013 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin Fehl, Fred, 1906-1995 Performing Arts Collection PA-00030 Scope and Contents Fred Fehl was born in 1906 in Vienna and lived there until he fled from the Nazis in 1938, arriving in New York in 1939. -

The Late Choral Works of Igor Stravinsky

THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY _________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ by RUSTY DALE ELDER Dr. Michael Budds, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, as appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY presented by Rusty Dale Elder, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________________ Professor Michael Budds ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary _______________________________________ Professor Timothy Langen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to each member of the faculty who participated in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I wish to recognize the ex- traordinary contribution of Dr. Michael Budds: without his expertise, patience, and en- couragement this study would not have been possible. Also critical to this thesis was Dr. Judith Mabary, whose insightful questions and keen editorial skills greatly improved my text. I also wish to thank Professor Timothy Langen for his thoughtful observations and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF STRAVINSKY’S LATE WORKS…....1 Methodology The Nature of Relevant Literature 2. “A BAD BOY ALL THE WAY”: STRAVINSKY’S SECOND COMPOSITIONAL CRISIS……………………………………………………....31 3. AFTER THE BOMB: IN MEMORIAM DYLAN THOMAS………………………45 4. “MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL”: CANTICUM SACRUM AD HONOREM SANCTI MARCI NOMINIS………………………………………………………...60 5. -

Michael Langlois

Winter 2 017-2018 B allet Review From the Winter 2017-1 8 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Heather Watts by Michael Langlois © 2017 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. 4 New York – Elizabeth McPherson 6 Washington, D.C. – Jay Rogoff 7 Miami – Michael Langlois 8 Toronto – Gary Smith 9 New York – Karen Greenspan 11 Paris – Vincent Le Baron 12 New York – Susanna Sloat 13 San Francisco – Rachel Howard 15 Hong Kong – Kevin Ng 17 New York – Karen Greenspan 19 Havana – Susanna Sloat 46 20 Paris – Vincent Le Baron 22 Jacob’s Pillow – Jay Rogoff 24 Letter to the Editor Ballet Review 45.4 Winter 2017-2018 Lauren Grant 25 Mark Morris: Student Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino and Teacher Managing Editor: Joel Lobenthal Roberta Hellman 28 Baranovsky’s Opus Senior Editor: Don Daniels 41 Karen Greenspan Associate Editors: 34 Two English Operas Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan Claudia Roth Pierpont Alice Helpern 39 Agon at Sixty Webmaster: Joseph Houseal David S. Weiss 41 Hong Kong Identity Crisis Copy Editor: Naomi Mindlin Michael Langlois Photographers: 46 A Conversation with Tom Brazil 25 Heather Watts Costas Associates: Joseph Houseal Peter Anastos 58 Merce Cunningham: Robert Gres kovic Common Time George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall Daniel Jacobson Paul Parish 70 At New York City Ballet Nancy Reynolds James Sutton Francis Mason David Vaughan Edward Willinger 22 86 Jane Dudley on Graham Sarah C. Woodcock 89 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photograph by Tom Brazil: Merce Cunningham in Grand Central Dances, Dancing in the Streets, Grand Central Terminal, NYC, October 9-10, 1987. -

—John Lahr Cussion

1 figure, or what Duchamp termed “retinal art”? The answer is all of the above. This beautifully installed, CRITIC’S NOTEBOOK whip-smart exhibition features works such as a cracked and cloudy crystal ball that was rolled from AW NE DAWN its place of purchase to the gallery, a collaboration between Nina Beier and Marie Lund; a series of paintings by Pavel Büchler, composed of fragments When it was first produced, from found flea-market canvases; Nina Canell’s al- in 1946, Garson Kanin’s chemical assemblage, in which a bowl of water dis- solving into mist hardens a nearby bag of cement; “Born Yesterday” made a and Monica Bonvicini’s fractured safety-glass cube, star of Judy Holliday, who which gives the finger to minimalism. Destroy away: art rises, ever phoenixlike, from the ashes. Through played Billie Dawn, the May 8. (Swiss Institute, 495 Broadway, at Broome bimbo turned bookworm. 1St. 212-925-2035.) The splendid new revival, directed by Doug Hughes DANCE at the Cort, makes a star NEW YORK CITY BALLET The company goes back to basics, with seven days of Balanchine’s “black-and-white” dances, modern- ist masterpieces that have come to define the style and look of twentieth-century American ballet. In “Apollo” (1928)—set, like many of these works, to music by Igor Stravinsky—a “wild, untamed youth,” the dancer Jacques d’Amboise says, “learns nobility through art.” “Episodes,” from 1959, began as a double bill shared by Martha Graham and George Balanchine, and hasn’t been performed here in four years. And “Concerto Barocco” (1941), for two violins and two ballerinas, comes as close to revealing the essence of Bach as any dance ever will. -

Dorathi Bock Pierre Dance Collection, 1929-1996

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pc33q9 No online items Finding Aid for the Dorathi Bock Pierre dance collection, 1929-1996 Processed by Megan Hahn Fraser and Jesse Erickson, March 2012, with assistance from Lindsay Chaney, May 2013; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ ©2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Dorathi Bock 1937 1 Pierre dance collection, 1929-1996 Descriptive Summary Title: Dorathi Bock Pierre dance collection Date (inclusive): 1929-1996 Collection number: 1937 Creator: Pierre, Dorathi Bock. Extent: 27 linear ft.(67 boxes) Abstract: Collection of photographs, performance programs, publicity information, and clippings related to dance, gathered by Dorathi Bock Pierre, a dance writer and publicist. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Language of the Material: Materials are in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Historic Performance

En l’air en Avril Historic Performance Reserve your tickets now for the University of Maryland Dance Ensemble’s reconstruction of Erika Thimey’s A Fear Not of One - Where: University of Maryland Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, Dance Theater - When: Thurs., April 14 through Sat., April 16 at 8 p.m., Sun., April 17 at 3 p.m. - Cost: $25 [$20 for subscribers] - Order tickets: In person at the Center ticket office 11 am – 9 pm 7 days Online: http://claricesmithcenter.umd.edu/2010/c/performances/performance?rowid=11322 By phone: at 301.405.ARTS (2787), by fax: 301.314.2683 By mail: Patron Services, Suite 3800, Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742-1625 About the reconstruction: “A Fear Not of One, But of Many” is double- cast with dancers who auditioned and spent countless hours studying with ETC members and Alvin Mayes of the UMD Dance Department. The students worked with archival materials to reconstruct and recreate this powerful dance created in 1951 in response to the threat of the atomic bomb. In addition to - A Fear Not of One: Dance artists of UMD’s School of Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies will present original works created and/or performed by undergraduate Dance students, and “Herencia” with choreography by Artist-in-Residence Adriane Fang. Show directed by Patrik Widrig. Parking and Directions: driving: http://claricesmithcenter.umd.edu/2010/c/about/parking/directions public transport: http://claricesmithcenter.umd.edu/2010/c/about/parking/transportation You are invited to a post-concert benefit for The Erika Thimey Dance & Theater Co. -

2017 Season 10:00 AM, Wheeler Opera House, $40.00 Edward Berkeley Director, Aspen Opera Center Artist- June 29 –August 20, 2017 Faculty

SATURDAY, JULY 1, 2017 Aspen Music Festival and School Opera Scenes Master Class 2017 Season 10:00 AM, Wheeler Opera House, $40.00 Edward Berkeley director, Aspen Opera Center artist- June 29 –August 20, 2017 faculty THURSDAY, JUNE 29, 2017 Chamber Music Violin Studio Class 4:30 PM, Harris Concert Hall, $45.00 1:00 PM, Edlis Neeson Hall, Free Donald Crockett conductor, Sarah Vautour soprano, Paul Kantor Elizabeth Buccheri piano, James Dunham viola, Anton Nel piano, Robert Chen violin, Cornelia Heard violin, Jonathan Chapel Chamber Music Haas percussion, Michael Mermagen cello, Bruce Bransby 4:15 PM, Aspen Chapel, Free bass, Aralee Dorough flute, Alison Fierst flute, Felipe Jimenez-Murillo clarinet, JJ Koh clarinet, Samuel Williams A Recital by Arnaud Sussmann violin David Finckel cello saxophone, Per Hannevold bassoon, Brian Mangrum horn, and Wu Han piano Joe Blumberg trumpet, Kevin Cobb trumpet, Michael 7:00 PM, Harris Concert Hall, $60.00 Powell trombone, Ingmar Beck conductor, Aspen BRAHMS: Cello Sonata No. 1 in E minor, op. 38 Contemporary Ensemble DVOŘÁK: Sonatina in G major, B. 183, op. 100 HYLA: Polish Folk Songs — WEILL: Berlin im Licht MENDELSSOHN: Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, op. 66 Je ne t’aime pas WEILL/BERIO: Surabaya Johnny from Happy End FRIDAY, JUNE 30, 2017 WEILL: Youkali from Marie Galante Aspen Chamber Symphony Dress Rehearsal I’m a Stranger Here Myself from One Touch of 9:30 AM, Benedict Music Tent, $20.00 Venus Ludovic Morlot conductor, Simone Porter violin HINDEMITH: Viola Sonata, op. 11, no. 4 R. STRAUSS: from Tanzsuite nach Klavierstücken von MILHAUD: La création du monde, op. -

Lawrence Morton Papers LSC.1522

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6d5nb3ht No online items Finding Aid for the Lawrence Morton Papers LSC.1522 Finding aid prepared by Phillip Lehrman, 2002; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 February 21. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Lawrence LSC.1522 1 Morton Papers LSC.1522 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Lawrence Morton papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1522 Physical Description: 42.5 Linear Feet(85 boxes, 1 oversize folder, 50 oversize boxes) Date (inclusive): 1908-1987 Abstract: Lawrence Morton (1904-1987) played the organ for silent movies and studied in New York before moving to Los Angeles, California, in 1940. He was a music critic for Script magazine, was the executive director of Evenings on the Roof, director of the Ojai Music Festival and curator of music at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The collection consists of books, articles, musical scores, clippings, manuscripts, and correspondence related to Lawrence Morton and his activities and friends in the Southern California music scene. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. -

THE SUZANNE FARRELL BALLET Thu, Dec 4, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2014 // 15 SEASON Northrop Presents THE SUZANNE FARRELL BALLET Thu, Dec 4, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage Swan Lake Allegro Brillante The Concert (Or, The Perils of Everybody) Natalia Magnicaballi and Michael Cook in Balanchine's Swan Lake. Photo © Rosalie O'Connor. Dear Northrop Dance Lovers, Northrop at the University of Minnesota Presents What a wonderful addition to our holiday season in Minnesota–a sparkling ballet sampler with the heart-lifting sounds of live classical music. Tonight’s presentation of The Suzanne Farrell Ballet is one of those “only at Northrop” dance experiences that our audiences clamor for. We’re so happy you are here to be a part of it. Suzanne Farrell is a name recognized and respected the world over as the legendary American ballerina and muse of choreographer George Balanchine. As a dancer, Farrell was SUZANNE FARRELL, Artistic Director in a class all her own and hailed as “the most influential ballerina of the late 20th century.” For most of her career, which spanned three decades, she danced at New York City Ballet, where her artistry inspired Balanchine to create nearly NATALIA MAGNICABALLI HEATHER OGDEN* MICHAEL COOK thirty works especially for her–most of them are masterpieces. ELISABETH HOLOWCHUK Christine Tschida. Photo by Patrick O'Leary, Since retiring from NYCB in 1989, Farrell has dedicated her University of Minnesota. life to preserving and promoting the legacy of her mentor. She has staged Balanchine ballets for many of the world’s VIOLETA ANGELOVA PAOLA HARTLEY leading companies, including St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Ballet (known at the time as Leningrad’s Kirov). -

Yhtenäistetty Igor Stravinsky

Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja 149 Yhtenäistetty Igor Stravinsky Heikki Poroila Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Helsinki 2012 Julkaisija Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Toimitustyö ja ulkoasu Heikki Poroila © Heikki Poroila 2012 01.4 POROILA , HEIKKI Yhtenäistetty Igor Stravinsky : teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo / Heikki Poroila. – Helsinki : Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys, 2012. – 30 s. : kuv. – (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja, ISSN 0784-0322 ; 149). ISBN 978-952-5363-48-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-5363-48-7 (PDF) 2 Yhtenäistetty Igor Stravinsky Todellinen kosmopoliitti Igor Fjodorovitš STRAVINSKY (18.6.1882 - 7.6.1971), kuten säveltäjä itse halusi nimensä kir- joittaa asetuttuaan Yhdysvaltoihin asumaan, syntyi Venäjällä muusikkosukuun, mutta lähti jo ennen Lokakuun vallankumousta maailmalle. Stravinsky palasi synnyinmaahansa vasta elä- mänsä loppupuolella, silloinkin vain käväisemään. Stravinsky saavutti menestystä ja kuuluisuutta jo nuorena miehenä. Vuonna 1913 järjes- tetty Le sacre du printemps -teoksen ensiesityksen skandaali oli kuin varmistus paikalle vuo- sisadan modernismin eturivissä. Säveltäjän myöhempi kehitys oli täynnä melkoisia käänteitä, ja hän on itsekin puhunut selkeistä vaiheista. ”Venäläisen” kauden jälkeen seurasi ”eurooppa- lainen” vaihe, joka muuttui monen ällistykseksi uusklassisismiksi, paluuksi menneille vuo- sisadoille. Stravinsky sävelsi myös runsaasti ortodoksiseen uskontoon kytkeytynyttä musiik- kia liityttyään vuonna 1926 takaisin kirkon jäseneksi. Tämä uskonnollisuus -

Serge Lifar George Balanchine

Emmanuel Thiry, histoire de la danse 21 1 Néo-classicisme. George Balanchine Serge Lifar La danse en Angleterre I. George Balanchine (1904-1983), გიორგი მელიტონის ძე ბალანჩივაძე (en Georgien) George Balanchine est un chorégraphe américain d'origine russe qui, avec Serge Lifar, fut l'un des principaux et des plus influents représentants du ballet néoclassique au XXe siècle. 1. Sa vie Fils d'un compositeur géorgien, il entre sans vocation à l'École impériale de danse de Saint- Pétersbourg à 10 ans. Diplômé à 17 ans, il intègre le Gatob1 qui traverse depuis 1917 des moments difficiles. Parallèlement il étudie le piano et la composition au Conservatoire de Petrograd2, espérant devenir compositeur. Cependant, dès 1920, il crée ses premières chorégraphies pour des galas ou des "soirées du jeune ballet ". En 1924, il quitte l'Union soviétique à l’occasion d’une tournée à l’étranger. Les danseurs sont engagés par Serge Diaghilev dans la compagnie des Ballets Russes. Diaghilev lui confie dès 1925 la chorégraphie des intermèdes d'opéras pour la saison d'hiver à Monte- Carlo. Il lui demande ensuite chaque année des créations. Les deux hommes se respectent mais gardent des relations distantes, même si Balanchine reconnaît devoir à Diaghilev la formation de son jugement esthétique. Il écrit « Diaghilev m’enseigna ce qu’était la danse vivante ». Balanchine reste aux Ballets russes jusqu'à leur disparition, en qualité de chorégraphe, et de danseur jusqu'en 1927, date à laquelle il a un accident au genou. En 1929, il collabore à un film à Londres, puis est invité à régler la chorégraphie des Créatures de Prométhée pour le Ballet de l'Opéra de Paris.