The Metamorphic Indo-Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

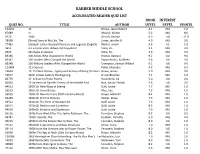

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

District Census Handbook, 33-Banda, Uttar

CENSUS 1961 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK UTTAR PRADESH 33-BANDA DISTRICT LUCKNOW: Superintendent, Printing and Stationery, U. P. (India) 1965 [Price Rs. 10.00 Preface: • Introduction I-CENSUS TABLES A-GENERAL POPULATION TABLES A-I Area, Houses and Population Appendix II-Number of Villages with a Population of 5,000 and over and Towns with Ii 6 Population unuer 5,000 6 Appendix Ill-Houseless and Institutional Population 6 A--II Variation in Population during Sixty Years 7 Appendix 1951 Population according to the territorial jurisdiction in 1951 and cbanges in area and population invalved in those changes 7 A-III Villages Classified by Population a A-IV Towns (and Town-groups) classified by Population in 1961 with Variation since 1941 9 Appendix New Towns added in 1961 and Towns in 1951 declassified in 1961 10 Explanatory Note to the Appendix 10 B-GENERAL ECONOMIC TABLES B-1 & II Workers and Non-workers in District and Towns classified by Sex and Broad Age-groups 12 B-III Part A-Industrial Classification of Workers and Non-workers by Educational Levels in Urban Areas only 18 Part B-Industrial Classification of Workers and Non-workers by Educational Levels in Rural Areas only 20 B-IV Part A-Industrial Classification by Sex and Class of Worker of Peraona at Work at Household Industry Part B-Industrial Classification by Sex and Class of Worker of Persons at Work in Non-household Industry, Trade, Business, Profession or Service 28 Part C-Industrial Classification by Sex and Divisions, Major Groups and Minor Groups of Persons at Work other than Cultivation 35 Occupational Claasification by Sex of Persons at Work other than Cultivation. -

1 Cacao Criollo

CACAO CRIOLLO: SU IMPORTANCIA PARA LA GASTRONOMÍA, EL TURISMO, CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO Y ALGUNAS PREPARACIONES A BASE DE SUS RESIDUOS Natali López Mejía1, Javier Alejandro Duarte Giraldo2, Jhan Carlos Nino Polo3, Yeimy Alexandra Rozo Betancourt4, Jhon Alejandro Huerfano Calderon5 y Juan Carlos Posso Gomez6 Revista de Institución 1Docente investigadora del programa de Tecnología en Gastronomía, Facultad de Turismo, Arte, Comunicación y Cultura, Universitaria Agustiniana, Ak. 86 #11b-95, Bogotá, Bogotá D.C., Patrimonio y Desarrollo Colombia, e-mail: [email protected]. 2Docente coordinador de alimentos y bebidas del programa de Tecnología en Gastronomía, Confederación Panamericana de Facultad de Arte, Comunicación y Cultura, Universitaria Agustiniana, Ak. 86 #11b-95, Bogotá, Escuelas de Bogotá D.C., Colombia, e-mail: [email protected] Hotelería, Gastronomía y 2Estudiante del programa de Tecnología en Gastronomía, Facultad de Arte, Comunicación y Turismo Cultura, Universitaria Agustiniana, Ak. 86 #11b-95, Bogotá, Bogotá D.C., Colombia, e-mail: (CONPEHT). [email protected] www.conpeht- 3Estudiante del programa de Tecnología en Gastronomía, Facultad de Arte, Comunicación y turpade.com Cultura, Universitaria Agustiniana, Ak. 86 #11b-95, Bogotá, Bogotá D.C., Colombia, e-mail: ISSN: 2448-6809 [email protected] Publicación 4Estudiante del programa de Tecnología en Gastronomía, Facultad de Arte, Comunicación y semestral Cultura, Universitaria Agustiniana, Ak. 86 #11b-95, Bogotá, Bogotá D.C., Colombia, -

GENESIS: Lesson 8 - “This Will Make Us Famous”

GENESIS: Lesson 8 - “This Will Make Us Famous” Genesis 10:1, 8-10 (NLT), “This is the account of the families of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, the three sons of Noah. Many children were born to them after the great flood… 8 C ush was also the ancestor of Nimrod, who was the first heroic warrior on earth. 9 S ince he was the greatest hunter in the world, his name became proverbial. People would say, “This man is like Nimrod, the greatest hunter in the world.” 10 H e built his kingdom in the land of Babylonia, with the cities of Babylon, Erech, Akkad, and Calneh.” →Nimrod’s pride leads him to build a city that would become Babylon, which is a type or picture in the Bible of human pride in rebellion against God. This idea finds its fullest description in the Book of Revelation, as God pronounces His final judgment on the pride and wickedness of mankind in the last days: Revelation 17:1-6 (NLT), “One of the seven angels who had poured out the seven bowls came over and spoke to me. “Come with me,” he said, “and I will show you the judgment that is going to come on the great prostitute, who rules over many waters. 2 T he kings of the world have committed adultery with her, and the people who belong to this world have been made drunk by the wine of her immorality.” So, the angel took me in the Spirit= into the wilderness. There I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast that had seven heads and ten horns, and blasphemies against God were written all over it. -

Chocolatiers and Chocolate Experiences in Flanders & Brussels

Inspiration guide for trade Chocolatiers and Chocolate Experiences IN FLANDERS & BRUSSELS 1 We are not a country of chocolate. We are a country of chocolatiers. And chocolate experiences. INTRODUCTION Belgian chocolatiers are famous and appreciated the world over for their excellent craftmanship and sense of innovation. What makes Belgian chocolatiers so special? Where can visitors buy a box of genuine pralines to delight their friends and family when they go back home? Where can chocolate lovers go for a chocolate experience like a workshop, a tasting or pairing? Every day, people ask VISITFLANDERS in Belgium and abroad these questions and many more. To answer the most frequently asked questions, we have produced this brochure. It covers all the main aspects of chocolate and chocolate experiences in Flanders and Brussels. 2 Discover Flanders ................................................. 4 Chocolatiers and shops .........................................7 Chocolate museums ........................................... 33 Chocolate experiences: > Chocolate demonstrations (with tastings) .. 39 > Chocolate workshops ................................... 43 > Chocolate tastings ........................................ 49 > Chocolate pairings ........................................ 53 Chocolate events ................................................ 56 Tearooms, cafés and bars .................................. 59 Guided chocolate walks ..................................... 65 Incoming operators and DMC‘s at your disposal .................................74 -

THE 10Th Sitting July 1982 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES

10th Sitting July 1982 THE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORTS [Volume 9] PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE SECOND SESSION (1982) OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE FOURTH PARLIAMENT OF GUYANA UNDER THE CONSTITUTION OF THE CO-OPERATIVE REPUBLIC OF GUYANA 10th Sitting 14:00 hrs Thursday, 1982-07-08 MEMBERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY (75) Speaker (1) *Cde. Sase Narain, O R., J.P., M.P. Speaker of the National Assembly Members of the Government - People’s National Congress (62) Prime Minister (1) *Cde. Dr. P.A. Reid, O.E., M.P., Prime Minister Other Vice-Presidents (4) Cde. S.S. Naraine, A.A., M.P., Vice-President, Works and Transport Cde. H.D. Hoyte, S.C., M.P., Vice-President, Economic Planning and Finance Cde. H. Green, M.P., Vice-President, Agriculture Cde. B. Ramsaroop, M.P., Vice-President, Party and State Matters Senior Ministers (7) Cde. R. Chandisingh, M.P., Minister of Education Cde. R.H.O. Corbin, M.P., Minister of National and Regional Development *Cde. F.E. Hope, M.P., Minister of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection *Cde. H O. Jack, M.P., Minister of Energy and Mines *Cde. Dr. M. Shahabuddeen, O.R., S.C., M.P., Attorney General and Minister of Justice *Cde. R.E. Jackson, M.P., Minister of Foreign Affairs *Cde. J.R. Thomas, M.P., Minister of Home Affairs *Non-elected Member 1 Ministers (7) Cde. U. E. Johnson, M.P., Minister of Co-operatives Cde. J. N. Maitland-Singh, M.P., Minister in the Ministry of Agriculture Cde. Sallahuddin, M.P., Minister, Finance, in the Ministry of Economic Planning and Finance *Cde. -

The Dougla Poetics of Indianness: Negotiating Race and Gender in Trinidad

The dougla poetics of Indianness: Negotiating Race and Gender in Trinidad Keerti Kavyta Raghunandan Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy Centre of Ethnicity and Racism Studies June 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © The University of Leeds, 2014, Keerti Kavyta Raghunandan Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Shirley Anne Tate. Her refreshing serenity and indefatigable spirit often helped combat my nerves. I attribute my on-going interest in learning about new approaches to race, sexuality and gender solely to her. All the ideas in this research came to fruition in my supervision meetings during my master’s degree. Not only has she expanded my intellectual horizons in a multitude of ways, her brilliance and graciousness is simply unsurpassed. There are no words to express my thanks to Dr Robert Vanderbeck for his guidance. He not only steered along the project to completion but his meticulous editing made this more readable and deserves a very special recognition for his patience, understanding, intelligence and sensitive way of commenting on my work. I would like to honour and thank all of my family. My father who was my refuge against many personal storms and who despite facing so many of his own battles, never gave up on mine. -

Untold Stories of the Past 150 Years, Canada 150 Conference, UCD

Untold Stories of the Past 150 Years, Canada 150 Conference, UCD [as of March 28, 2017 and subject to change] Friday, April 28, 2017 Registration: 11.30 am to 1 pm, Humanities Institute 1.00 pm – 2.15 pm: Panels - Panel 1A (Humanities Institute): Urban Indigenous Experiences Aubrey Hanson (Métis, University of Calgary), “Indigenous Women’s Resilience in Urban Spaces” Jeff Fedoruk (McMaster University), “Unceded Identities: Vancouver as Nexus of Urban Indigenous Cultural Production” Renée Monchalin (Métis, Algonquin, Huron; University of Toronto), “The Invisible Nation: Métis Identity, Access to Health Services, and the Colonial Legacy in Toronto, Canada” - Panel 1B (Geary Institute): Disrupting Normative Bodies and Gendered Discourses Kit Dobson (Mount Royal University), “Untold Bodies: Failing Gender in Canada’s Past and Future” Kristi Allain (St. Thomas University), “Taking Slap Shots at the House: When the Canadian Media turns Curlers into Hockey Players” Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw (Memorial University), “Listening Between the Lines: Curating the Normative Canadian” Jamie Jelinski (Queen’s University), “‘An Artist’s View of Tattooing’: Aba Bayefsky and Tattooing in Toronto and Yokohoma, 1978-1986” 2.15 pm – 2.30 pm: Break 2.30 pm – 3.45 pm: Panels - Panel 2A (Humanities Institute): Indigenous Aesthetics Sarah MacKenzie (University of New Brunswick), “Indigenous Women’s Theatre: A Tool of Decolonization” Lisa Boivin (Deninu Kue, University of Toronto), “Painting the Path of Indigenous Resilience: In this Place Settlers Call Canada” Shannon Webb-Campbell (Mi’kmaq, Memorial University), “On Reading Yourself Native: Notes from an Indigenous Poet to Established Aboriginal Writers” - Panel 2B (Geary Institute): Untold Diasporas Dagmara Drewniak (Adam Mickiewicz University), “‘We were coming back. -

Celebrating Our Calypso Monarchs 1939- 1980

Celebrating our Calypso Monarchs 1939-1980 T&T History through the eyes of Calypso Early History Trinidad and Tobago as most other Caribbean islands, was colonized by the Europeans. What makes Trinidad’s colonial past unique is that it was colonized by the Spanish and later by the English, with Tobago being occupied by the Dutch, Britain and France several times. Eventually there was a large influx of French immigrants into Trinidad creating a heavy French influence. As a result, the earliest calypso songs were not sung in English but in French-Creole, sometimes called patois. African slaves were brought to Trinidad to work on the sugar plantations and were forbidden to communicate with one another. As a result, they began to sing songs that originated from West African Griot tradition, kaiso (West African kaito), as well as from drumming and stick-fighting songs. The song lyrics were used to make fun of the upper class and the slave owners, and the rhythms of calypso centered on the African drum, which rival groups used to beat out rhythms. Calypso tunes were sung during competitions each year at Carnival, led by chantwells. These characters led masquerade bands in call and response singing. The chantwells eventually became known as calypsonians, and the first calypso record was produced in 1914 by Lovey’s String Band. Calypso music began to move away from the call and response method to more of a ballad style and the lyrics were used to make sometimes humorous, sometimes stinging, social and political commentaries. During the mid and late 1930’s several standout figures in calypso emerged such as Atilla the Hun, Roaring Lion, and Lord Invader and calypso music moved onto the international scene. -

A Queer Vision of Nation Through Nostalgic Diaspora in Shani Mootoo’S Cereus Blooms at Night

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(2): 8814-8821 ISSN: 00333077 A queer vision of Nation through nostalgic Diaspora in Shani Mootoo’s Cereus Blooms at Night 1Saikat Majumdar, 2Dr. Sandip Sarkar 1Ph.D Scholar, National Institute of Technology, Raipur 2Assistant Professor, National Institute of Technology, Raipur Abstract One of the key themes of Shani Mootoo's Cereus Blooms at Night is passing through various locations. The thematic specialization, which is decisive for debates, is expressed in physiological features and presence of the Caribbean diaspora. I try to see the novel by Mootoo as a text that not only reintroduces and reforms the unique affiliation, but also the physical and social space. She points out the value of shifting diverse bodies across different areas and interactions with each other's community by constructing a living environment that re-imagines and displaces belonging. This reveals that the vengeful concepts of belonging, diaspora history, and nationalism that run deep inside the nostalgia of the novel are embedded. Decolonization may be a scientific approach in Mootoo's novel that challenges and contradicts heteronormative ideologies as it leaves space for multiple forms of belonging by beginning to ‘to challenge, to unsettle, to queer’.(Z.Pecic.Queer Narratives of the Caribbean Diaspora, 2013.) Keywords: Nation, queer, gender, sexuality, diaspora. Article Received: 10 August 2020, Revised: 25 October 2020, Accepted: 18 November 2020 Introduction become a major theme- both in both South Asian and Shani Mootoo's Cereus Blooms at Night (1996) is based Caribbean literatures. Natural disasters, refugee on a fictitious Caribbean island. It's posing itself between problems, and political upheavals have forced human life the Caribbean and Canada, by their protagonists' effort to be more uncertain than ever before. -

Beyond Créolité and Coolitude, the Indian on the Plantation: Recreolization in the Transoceanic Frame

Middle Atlantic Review of Latin American Studies, 2020 Vol. 4, No. 2, 174-193 Beyond Créolité and Coolitude, the Indian on the Plantation: Recreolization in the Transoceanic Frame Ananya Jahanara Kabir Kings College London [email protected] This essay explores the ways in which Caribbean artists of Indian heritage memorialize the transformation of Caribbean history, demography, and lifeways through the arrival of their ancestors, and their transformation, in turn, by this new space. Identifying for this purpose an iconic figure that I term “the Indian on the Plantation,” I demonstrate how the influential theories of Caribbean identity-formation that serve as useful starting points for explicating the play of memory and identity that shapes Indo-Caribbean artistic praxis—coolitude (as coined by Mauritian author Khal Torabully) and créolité (as most influentially articulated by the Martinican trio of Jean Barnabé, Patrick Chamoiseau, and Raphaël Confiant)—are nevertheless constrained by certain discursive limitations. Unpacking these limitations, I offer instead evidence from curatorial and quotidian realms in Guadeloupe as a lens through which to assess an emergent artistic practice that cuts across Francophone and Anglophone constituencies to occupy the Caribbean Plantation while privileging signifiers of an Indic heritage. Reading these attempts as examples of decreolization that actually suggest an ongoing and unpredictable recreolization of culture, I situate this apparent paradox within a transoceanic heuristic frame that brings -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

THE LAND RIGHTS OF GUYANA'S INDIGENOUS PEOPLES CHRISTOPHER ARIF BULKAN A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Law YORK UNIVERSITY Toronto, Ontario May 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-38989-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-38989-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.