Journal of Social and Political Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIP Imphal West

1 DISTRICT INDUSTRIAL POTENTIAL SURVEY REPORT OF IMPHAL WEST DISTRICT 2016-17 (Up dated) Industrial Profile of Imphal West; --- 1. General Characteristic of the District; Imphal West District came into existence on 18th June 1997 when the erstwhile Imphal District was bifurcated into two districts namely, (1) Imphal West (2) Imphal East district. Imphal West is an agrarian district. Farming is subsistence type. Rice, Pules, Sugarcane and Potato are the main crops. Small quantities of wheat, maize and oilseeds are also grown. The agro climate conditions are favorable for growing vegetables and cereal crops in the valley region. The District enjoys comfortable temperature throughout the year, not very hot in summer and not very cold in winter. Overall the climate condition of the district is salubriousness and monsoon tropical. The whole district is under the influence of the monsoons characterized by hot and humid rainy seasons during the summer. 1.1 LOCATION & GEOGRAPHICAL AREA;--- Imphal West District falls in the category of Manipur valley region. It is a tiny plain at the centre of Manipur surrounded by Plains of the district. Imphal City, the state capital is the functional centre of the district. As a first glance, we may summarize in the table. It is surrounded by Senapati district on the north, on the east by Imphal East and Thoubal districts, on the south by Thoubal and Bishnupur, and on the west by Senapati and Bishnupur districts respectively. The area of the district measured 558sq.km. only and it lies between 24.30 N to 25.00 N and 93.45 E to 94.15 E. -

Development and Disaster Management Amita Singh · Milap Punia Nivedita P

Development and Disaster Management Amita Singh · Milap Punia Nivedita P. Haran Thiyam Bharat Singh Editors Development and Disaster Management A Study of the Northeastern States of India Editors Amita Singh Nivedita P. Haran Centre for the Study of Law Disaster Research Programme (DRP) and Governance Jawaharlal Nehru University Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi, Delhi, India New Delhi, Delhi, India Thiyam Bharat Singh Milap Punia Centre for Study of Social Exclusion Centre for the Study of Regional and Inclusive Policy Development Manipur University Jawaharlal Nehru University Imphal, Manipur, India New Delhi, Delhi, India ISBN 978-981-10-8484-3 ISBN 978-981-10-8485-0 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8485-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018934670 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

First Northeast India Women Peace Congregation

1 Content Introduction…………………..……………………………………………….3 Program Schedule…………………………………………………………….6 Profile of Speakers...………………………………………………………….6 Background Paper on Women Peace & Security……………………………13 Speeches of the Women Peace Congregation……………………………….18 Recommendations to Take Further.…………………………………………40 Participants…..………………………………………………………………42 Media Coverage……….…………………………………………………….46 Annexures……...……………………………………………………………47 2 Introduction: Northeast India is a region of India that borders five countries and comprises the eight states— Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura and Sikkim. The total population of Northeastern Region of India is 38,857,769, of which 19.1% are living below the poverty line. Northeast India deals with complex social political issues such as struggle over natural resources, ethnic conflicts, illegal migration, displacement and social exclusion. Status of Violence against Women in Northeast India: The incidences of crimes against women, particularly domestic violence, are on the rise in Northeast India. Reported instances of crimes against women in Assam jumped to 17,449 in 2013 as against 13,544 the previous year. In Tripura, between 2013 and the previous year, it had risen to 1,628 from 1,559 while Meghalaya saw a jump to 343 from 255. In Arunachal Pradesh, it was up from 201 to 288, in Sikkim to 93 from 68 and in Nagaland to 67 from 51.Manipur and Mizoram, however, recorded a slide in crimes against women with the incident rate in the former falling to 285 from 304 while the latter saw it drop from 199 to 177. (Source: National Crime Records Bureau, 2014). The main gender impact of the armed conflict taking place in Manipur and other states of Northeast India is the use of sexual violence as an arm of war. -

Chapter – 3 (Three) Research Methodology

Chapter – 3 (Three) Research Methodology 3.1 Introduction The present part of the study is about the methodology that has been adopted in order to carry out the present study. Methodology acts as a guide in conducting research studies and hence, mentioning the methodology is required to know the research design on the basis of which the research study would be carried out. The present chapter begins with the identification research questions, delineates the objectives aimed to be achieved and the hypotheses to be tested. The chapter also presents the framework of the study and the research design adopted in order to derive at the result and inferences with regard to the “Marketing Practices of Women Entrepreneurs of Manipur with reference to select Marketing Mix”. The framework of the study delineates the step wise process through which the study has been conducted. The relevant research methods and tools which have been employed are also mentioned in this chapter. It is structured in such a way that it begins with the identification of the nature of present research study, then continues with the identification of the respective tools and techniques that can be used under the specific type of research, also the identification of the data that are required for the study and the procedure of collecting the required data; and next is the verification of the sources from which data are to be obtained involving identification of the population of the study and from it, obtaining the required sample size of the study, designing of the tool for obtaining data from the sources such as questionnaire and personal field interview, and finally ends with the framing of the design for analysis and interpretation of the collected data so as to enable to form a basis [97] for drawing conclusions and then making suggestions to the women entrepreneurs of Manipur for better performance and effectiveness in marketing their products. -

A STUDY of IMA KEITHEL in IMPHAL WEST, MANIPUR a Dissertation Submitted To

WOMEN’S ROLE IN THE INFORMAL MARKET ECONOMY - A STUDY OF IMA KEITHEL IN IMPHAL WEST, MANIPUR A Dissertation submitted to Sikkim University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Philosophy by KRIPASHREE BACHASPATIMAYUM Department of Economics School of Social Sciences February 2020 \ TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: WOMEN AT INFORMAL WORK IN AN URBAN ECONOMY PAGE 1- 18 1.1 Women’s Roles in Economic Development - An Introduction 1.2 Statement of the Problem 1.3 Review of Literature 1.3.1 WID/WAD/GAD Approaches to Women’s Work 1.3.1.1 Women in Development 1.3.1.2 Women and Development 1.3.1.3 Gender and Development 1.3.2 Theories of Informal Work 1.3.1.3 Gender and Development 1.3.2.1 The Dualistic Explanation 1.3.2.2 The Structuralistic Explanation 1.3.2.3 The Legalistic Explanation 1.3.3 Women in the Informal Economy - International Experiences 1.3.4 Gaps in the Literature 1.4 Research Design 1.4.1 Research Objectives 1.4.2 Research Questions 1.4.3 Research Hypotheses 1.5 Methodology of the Study 1.6 Chapterisation of the Study Chapter 2: GENDER DEMOGRAPHY OF NORTH EAST INDIA AND MANIPUR PAGE NO: 19-30 2.1 Regional Population in North East India 2.2 Long-run Population Growth in the North East 2.3 Longterm Growth of Manipur Population 2.4 Gender Population Trends in Manipur 2.5 Regional Distribution of Manipur Population Chapter 3: WOMEN’S WORK PARTICIPATION IN NORTH EAST INDIA AND MANIPUR PAGE NO: 31-42 3.1 Regional Workforce in North East India 3.2 Main and Marginal Workforce 3.3 Worker Occupations in North -

Manipur Has Now Become the State with the Lowest Sex Ratio in India

Increasing gender disparity and its implications for Manipur Manipur has now become the state with the lowest sex ratio in India. By Govind Singh | Updated on: Nov. 22, 2020 Women vendors and shoppers at Ima market, Imphal, Manipur (PHOTO: IFP) The Northeast of India has always been the beacon of hope for gender equality and women’s rights. While the region does have internal societal challenges, they are nothing compared to the challenges faced by women in several other parts of the country. Manipur has always stood out in this regard and is one of the few states that provide a good example of the place a woman should be given in the family and in society. But it seems that is no longer the case. While women continue to enjoy a somewhat equitable status in Manipuri society, the future of women in Manipur is now looking bleak and shrouded with uncertainty. A recent report published by the Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner of the Government of India has brought forward some alarming statistics for Manipur. According to its Annual Report on Vital Statistics of India based on the Civil Registration System, the sex ratio at birth in Manipur has fallen to as low as 757. This means that for every 1,000 male children born in Manipur, only 757 female children are being born. It is not just this figure which is alarming. What is equally alarming is the fact that as per this report, Manipur has now become the state with the lowest sex ratio in India. -

Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The present study attempts to assess the livelihood and human security among women in Manipur. The study also tries to understand the context of women towards vulnerability and to explore the relationship between livelihood assets, problems, coping strategies and human security. Every aspect of human life changes so fast in all directions – in terms of social, cultural, economic, political, ecological, intellectual, professional, psychological, and technological dimensions in human living. These kinds of shift make people change in their living conditions, perspectives and belief system – looking forward to a new way of life expecting more comfortable and improved, but it is neither easy to reach that condition of living nor enough at once if one can. Simultaneously, there is an emergence of new problems and challenges – to achieve the goal as well as to make the achieved sustainable. Sustainability becomes significant considering questions on livelihood so that one has to be in a position to cope with any kind of precarious situations and disturbances in continuing those ways of living. At the same time, the human population is increasing day-by-day, leading to a context where there is a rapidly growing demand for resources for human consumption. There is a huge difference between educated-uneducated, trained-untrained, skilled- unskilled and professional-nonprofessional in grasping the opportunities in various fields like employment, accessibility and public distribution systems. As a result, the class difference has become wider in every society. In other words, as poverty becomes one of the biggest challenges in the developmental process of every society, there is a growing socio-economic and developmental gap regionally and politically. -

A Checklist of Traditional Edible Bio-Resources from Ima Markets of Imphal Valley, Manipur, India

JoTT SHORT COMMUNI C ATION 2(11): 1291-1296 A checklist of traditional edible bio-resources from Ima markets of Imphal Valley, Manipur, India Oinam Sunanda Devi 1, Puspa Komor 2 & Dhritiman Das 3 1 Research Scholar, Department of Zoology, Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam 781014, India 2 Junior Research Fellow, Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development (OKDISCD), VIP Road, Upper Hengrabari, Guwahati, Assam 781036, India 3 PhD Scholar, Conservation Science, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), 5th ‘A’ Main Road, Hebbal, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560024, India Email: 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected] Abstract: A study was conducted at seven important markets Imphal Valley, which extends north-south in the middle of Imphal Valley, Manipur in northeastern India, which are run for over 1795km2 (Singh et al. 1996). The Imphal Valley exclusively by women and are popularly known as “the Ima markets”. The two year study was to find out the important forms only 8.25% of the total area of Manipur while the edible bio-resources which are consumed daily by the local remaining 91.75% is hills (Singh 2006). Although the people of Manipur. Regular surveys were conducted at the valley constitutes only a small part of the geographical selected markets at least three times a month. A total of 45 wild area, two-thirds of Manipur’s 1.8 million people live in the edible plants and 26 wild fruits were identified during the survey. Also, 25 edible animal resources were recorded. It is suggested Imphal Valley (Roy 1992). -

8 March Page 1

Evening daily Imphal Times Regd.No. MANENG /2013/51092 Volume 6, Issue 393, Friday, March 8, 2019 Maliyapham Palcha kumsing 3416 www.imphaltimes.com Rs. 2/- Governor leads the state in celebrating Pravish Chanam’s Death Case International Women’s Day Disposed By The CJM, Gautam DIPR Speaking at the occasion as rendering social work in the most important key to Imphal, March 8, the Chief Guest, she also empowering the marginalised socio-economic Budha Nagar stated that she has always women population of the development. She further said IT News assist or undertake the local police to unearth such Hon’ble Governor of been a great supporter of State. that the International Imphal March 8, investigation of better conspiracy.” Manipur, Dr. Najma A women’s rights and cause of Stating that the present Women’s Day is an professional management of Here lies the dilemma that Heptulla lauded the women empowerment. Government has stepped opportunity to transform this Youth’s Forum for Protection Investigation. Hence, this Who is investigating the womenfolk or ‘Imas’ of I move the resolution for 33% down at micro level for momentum into action, to of Human Rights (YFPHR) case was not found suitable disposed case of Pravish Manipur for their genuine reservation of women in the promoting the welfare of empower women in all regret to learn that the death to be taken up for the Chanam by the CJM, Gautam courage in times of Parliament as early as 1995. women, Chief Minister N settings. “Gender equality is of Pravish Chanam’s case investigation by CBI and the Budh Nagar? challenging state issues Let us be strong and judge Biren mentioned that loans the first step to women have been disposed without decision of Govt. -

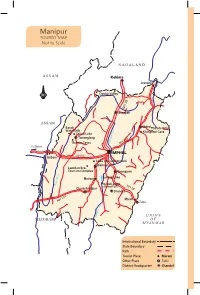

Manipur Tourist Map Not to Scale

Manipur TOURIST MAP Not to Scale Dzüko Valley Barak Sirohi Hills Waterfalls Zeilad Lake Tharon Caves Manipur River NH 150 Sadu Chiru Waterfalls Lamdan Eco- Tourism Complex Khongjom Loktak Lake Barak River NH 39 NH 150 International Boundary State Boundary Path Tourist Place Maram Other Place Tallui District Headquarter Chandel Manipur Manipur Little Paradise he erstwhile princely state of Manipur is a jewel of India. It is the power house of sports in India. A land Twith its bounteous vistas of untrammeled natural beauty and ancient traditions. An oval valley surrounded by seven blue hills, it is the home of colorful communities. The serenity of these pristine and isolated environs has permeated the lifestyle of these people with a lavish hand, allowing them to live for centuries in harmony. The wondrous balance of the flora and fauna abound Young leaves of cycas in its environs. Almost 70 per cent of the land is under forest cover. The stunning combination of wet forests, temperate forests and pine forests sustain a host of rare and endemic flora and fauna. Manipur is home to about 500 varieties of orchids of which 472 have been identified. Some of the world’s rarest orchids spring from the fertile soil and hang on the trees. Denizens of the forest include the rare hoolock gibbon, spotted linshang (python) and slow loris amongst other rare fauna. Indigenous to Manipur’s rich natural heritage is the Sangai – (State Animal) the dancing deer, a rare A dancer of animal that is facing extinction, can be found on the Manipuri Ras Leela unique vegetal floating biomass on the side of Loktak Lake. -

1. AGRONOMY CATEGORY (CROP): RICE Cereals Rice 1

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE, IROISEMBA, MANIPUR M.Sc. Sl. Title of thesis Name of the Major Subject Year of No. Student complet ion 1. AGRONOMY CATEGORY (CROP): RICE Cereals Rice 1. Studies on Weed Control in the Transplanted Rice L Chaoba Agronomy 1993 and its Economics Implications Singh (weed management) 2. Effects of Levels and Method of Application of M Gyanendro (Agronomy 1993 Nitrogen on the Yield of Transplanted Rice Singh Nutrient management) 3 A Study on Rice Based Intercropping System N Manileima Agronomy 1995 Under Upland Rainfed Condition Devi (cropping system) 4. Effect of Age of Seedling and Spacing on the Yield K Nandini Devi Agronomy 1996 of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Variety Norin-18 (Agrotechnique) 5. Effect of Levels of Nitrogen on the Growth and S Jugindro Agronomy 1996 Yield of Transplanted Rice Singh (Nutrient management) 6. Effect of Seedling Age Cutting Height and Nitrogen A Sanatombi Agronomy 1998 Requirement on Economics and Yield of Main- Devi (Nutrient ratoon Rice Sequence management) 7. Study on the Effect of Different Sources of Organic Oinam Bidur Agronomy 1997 Nitrogen With and Without Inorganic Nitrogenous Singh (Nutrient Fertilizer on the Yield Rice (Oryza sativa L.) management) 8. Effect of Cyanobacteria and Azolla Biofertilizers in M Amutombi Agronomy 1997 Conjunction with Nitrogenous Fertilizer on the Singh (Nutrient Productivity of Rainfed Lowland Rice management) 9. Effect on Spacing and Number of Seedling per Hill Khumlo Levish Agronomy 2001 on the Yield of Transplanted Rice Under Rainfed Chongloi (Agro- Condition technique) 10. Effect of Different Sources of Phosphorous and Sakhen Agronomy 2004 Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria on Yield and Sorokhaibam (Nutrient Nutrient Uptake to rice (Oryza Sativa L. -

Chlorophyll Content of Some Selected Edible Plants Sourced from Ima Market, Manipur, India

International Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences-IJPBSTM (2019) 9 (2): 1251-1259 Online ISSN: 2230-7605, Print ISSN: 2321-3272 Research Article | Biological Sciences | Open Access | MCI Approved UGC Approved Journal Chlorophyll Content of Some Selected Edible Plants Sourced from Ima Market, Manipur, India Jessia G1, Th. Bhaigyabati1, Suchitra S1, G.C. Bag2, L. Ranjit Singh2, P. Grihanjali Devi2* 1Institutional Advanced Level Biotech Hub, Imphal College, Imphal, Manipur, 795001 2Department of Chemistry, Imphal College, Imphal, Manipur, 795001 Received: 11 Jan 2019 / Accepted: 16 Mar 2018 / Published online: 1 Apr 2019 Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Abstract Consumption of fresh green leaves as vegetables or as condiments has been on the rise for their nutritive values and specially to counterbalance the increasing number of degenerative diseases. Chlorophyll which is the most abundant pigments in green plants is of great importance in human diet not only as food colorant but also as healthy food ingredients. Recent research shows that estimating the chlorophyll content could help in understanding the medicinal properties of the plants. Hence, the more the chlorophyll content the more nutritious the leaves will be. In the present study, chlorophyll pigments were extracted and estimated from 19 selected plant species viz: Eryngium foetidum, Allium fistulosum, Allium tuberosum, Allium hookeri, Coriandrum sativum, Plantago major, Zanthoxylum acanthopodium, Houttuynia cordata, Polygonum posumber, Ocimum canum, Brassica juncea, Hibiscus cannabinus, Oenanthe javanica, Ipomoea aquatica, Meyna laxiflora, Mentha spicata, Centella asiatica, Phlogacanthus thyrsiformis and Leucus aspera using 80% acetone, methanol and 95% ethanol as solvents. Results of the study showed that P. posumber has the highest concentration (Chl a 16.977μg/ml, Chl b 7.524 μg/ml) and lowest concentration was noted in Hibiscus cannabinus (Chl a 0.102μg/ml, Chl b 0.336μg/ml) using 80% acetone.