Reproductive Biology and Range Extension for Mobula Kuhlii Cf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manta Or Mobula

IOTC-2010-WPEB-inf01 Draft identification guide IOTC Working Party on Ecosystems and Bycatch (WPEB) Victoria, Seychelles 27-30 October, 2010 Mobulidae of the Indian Ocean: an identification hints for field sampling Draft, version 2.1, August 2010 by Romanov Evgeny(1)* (1) IRD, UMR 212 EME, Centre de Recherche Halieutique Mediterraneenne et Tropicale Avenue Jean Monnet – BP 171, 34203 Sete Cedex, France ([email protected]) * Present address: Project Leader. Project “PROSpection et habitat des grands PElagiques de la ZEE de La Réunion” (PROSPER), CAP RUN, ARDA, Magasin n°10, Port Ouest, 97420, Le Port, La Réunion, France. ABSTRACT Draft identification guide for species of Mobulidae family, which is commonly observed as by-catch in tuna associated fishery in the region is presented. INTRODUCTION Species of Mobulidae family are a common bycatch occurs in the pelagic tuna fisheries of the Indian Ocean both in the industrial (purse seine and longline) and artisanal (gillnets) sector (Romanov 2002; White et al., 2006; Romanov et al., 2008). Apparently these species also subject of overexploitation: most of Indian Ocean species marked as vulnerable or near threatened at the global level, however local assessment are often not exist (Table). Status of the species of the family Mobulidae in the Indian Ocean (IUCN, 2007) IUCN Status1 Species Common name Global status WIO EIO Manta birostris (Walbaum 1792) Giant manta NT - VU Manta alfredi (Krefft, 1868) Alfred manta - - - Mobula eregoodootenkee Longhorned - - - (Bleeker, 1859) mobula Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, Spinetail mobula NT - - 1841) Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, Shortfin devil ray NE - - 1841) Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, Chilean devil ray DD - VU 1892) Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908) Smoothtail NT - - mobula Lack of the data on the distribution, fisheries and biology of mobulids is often originated from the problem with specific identification of these species in the field. -

Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan2)

MALAYSIA NATIONAL PLAN OF ACTION FOR THE CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF SHARK (PLAN2) DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND AGRO-BASED INDUSTRY MALAYSIA 2014 First Printing, 2014 Copyright Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Department of Fisheries Malaysia. Published in Malaysia by Department of Fisheries Malaysia Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Malaysia, Level 1-6, Wisma Tani Lot 4G2, Precinct 4, 62628 Putrajaya Malaysia Telephone No. : 603 88704000 Fax No. : 603 88891233 E-mail : [email protected] Website : http://dof.gov.my Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 978-983-9819-99-1 This publication should be cited as follows: Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014. Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2), Ministry of Agriculture and Agro- based Industry Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia. 50pp SUMMARY Malaysia has been very supportive of the International Plan of Action for Sharks (IPOA-SHARKS) developed by FAO that is to be implemented voluntarily by countries concerned. This led to the development of Malaysia’s own National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark or NPOA-Shark (Plan 1) in 2006. The successful development of Malaysia’s second National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2) is a manifestation of her renewed commitment to the continuous improvement of shark conservation and management measures in Malaysia. -

First Record of Mobula Japonica (Muller Et Hentle), a Little Known Devil Ray from the Gulf of Thailand (Pisces : Mobulidae)

FIRST RECORD OF MOBULA JAPONICA (MULLER ET HENTLE), A LITTLE KNOWN DEVIL RAY FROM THE GULF OF THAILAND (PISCES : MOBULIDAE) Thosaporn Wongratana* Abstract A specimen of young Mobulajaponica (Muller & Henle), measured 661 rom across wings, is here described together with a note on the sight ing of 12 big specimens from Koh Chang, Trat Province, in the Gulf of Thailand. This is the first documentary report of the family Mobulidae for Thailand and of. the species for the South China Sea. Previously, the species were occasionally recorded from Japan, Honolulu, Samoa, Korea and Taiwan waters. Its inferior mouth with a band of teeth in both jaws, the very long whip-liked tail, and a prominent serrated caudal spine pro vide the main distinct characteristics and separate it from other related species. The full measurements of this young specimen and of the Naga Expedition's specimen of Mobula diabolus (Shaw), taken from Cambodian water, are also given. Introduction Jn order to update the knowledge of marine fish fauna of Thailand, regular observation of fish landing and occasional procurement of fish specimens are made at the Bangkok Wholesale Fish Market, operated by the Fish Marketing Organization of the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. On 4 December 1973, the author came across a young devil ray or sea devil, known in Thai "Pia rahu" (uom»). The fish measured 661 mm across the width. He has no hesitati~ns to make a further look for other specimens. And this led him to spot other 8 big males and 3 females of about the same size. -

Mobulid Rays) Are Slow-Growing, Large-Bodied Animals with Some Species Occurring in Small, Highly Fragmented Populations

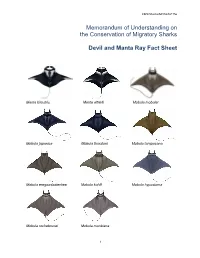

CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Devil and Manta Ray Fact Sheet Manta birostris Manta alfredi Mobula mobular Mobula japanica Mobula thurstoni Mobula tarapacana Mobula eregoodootenkee Mobula kuhlii Mobula hypostoma Mobula rochebrunei Mobula munkiana 1 CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e . Class: Chondrichthyes Order: Rajiformes Family: Rajiformes Manta alfredi – Reef Manta Ray Mobula mobular – Giant Devil Ray Mobula japanica – Spinetail Devil Ray Devil and Manta Rays Mobula thurstoni – Bentfin Devil Ray Raie manta & Raies Mobula Mobula tarapacana – Sicklefin Devil Ray Mantas & Rayas Mobula Mobula eregoodootenkee – Longhorned Pygmy Devil Ray Species: Mobula hypostoma – Atlantic Pygmy Devil Illustration: © Marc Dando Ray Mobula rochebrunei – Guinean Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana – Munk’s Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii – Shortfin Devil Ray 1. BIOLOGY Devil and manta rays (family Mobulidae, the mobulid rays) are slow-growing, large-bodied animals with some species occurring in small, highly fragmented populations. Mobulid rays are pelagic, filter-feeders, with populations sparsely distributed across tropical and warm temperate oceans. Currently, nine species of devil ray (genus Mobula) and two species of manta ray (genus Manta) are recognized by CMS1. Mobulid rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (1 young every 2-3 years), and a late age of maturity (up to 8 years), resulting in population growth rates among the lowest for elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al. 2014; Pardo et al 2016). 2. DISTRIBUTION The three largest-bodied species of Mobula (M. japanica, M. tarapacana, and M. thurstoni), and the oceanic manta (M. birostris) have circumglobal tropical and subtropical geographic ranges. The overlapping range distributions of mobulids, difficulty in differentiating between species, and lack of standardized reporting of fisheries data make it difficult to determine each species’ geographical extent. -

Elasmobranchs (Sharks and Rays): a Review of Status, Distribution and Interaction with Fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/277329893 Elasmobranchs (sharks and rays): a review of status, distribution and interaction with fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean CHAPTER · JANUARY 2015 READS 81 2 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Jeremy J Kiszka Florida International University 52 PUBLICATIONS 389 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Jeremy J Kiszka Retrieved on: 16 October 2015 OFFSHORE FISHERIES OF THE SOUTHWEST INDIAN OCEAN: their status and the impact on vulnerable species OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE Special Publication No. 10 Rudy van der Elst and Bernadine Everett (editors) The Investigational Report series of the Oceanographic Research Institute presents the detailed results of marine biological research. Reports have appeared at irregular intervals since 1961. All manuscripts are submitted for peer review. The Special Publication series of the Oceanographic Research Institute reports on expeditions, surveys and workshops, or provides bibliographic and technical information. The series appears at irregular intervals. The Bulletin series of the South African Association for Marine Biological Research is of general interest and reviews the research and curatorial activities of the Oceanographic Research Institute, uShaka Sea World and the Sea World Education Centre. It is published annually. These series are available in exchange for relevant publications of other scientific institutions anywhere in the world. All correspondence in this regard should be directed to: The Librarian Oceanographic Research Institute PO Box 10712 Marine Parade 4056 Durban, South Africa OFFSHORE FISHERIES OF THE SOUTHWEST INDIAN OCEAN: their status and the impact on vulnerable species Rudy van der Elst and Bernadine Everett (editors) South African Association for Marine Biological Research Oceanographic Research Institute Special Publication No. -

Mobula Munkiana) in the Gulf of California, Mexico Marta D

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Description of frst nursery area for a pygmy devil ray species (Mobula munkiana) in the Gulf of California, Mexico Marta D. Palacios1,2, Edgar M. Hoyos‑Padilla2,4, Abel Trejo‑Ramírez2, Donald A. Croll3, Felipe Galván‑Magaña1, Kelly M. Zilliacus3, John B. O’Sullivan5, James T. Ketchum2,6 & Rogelio González‑Armas1* Munk’s pygmy devil rays (Mobula munkiana) are medium‑size, zooplanktivorous flter feeding, elasmobranchs characterized by aggregative behavior, low fecundity and delayed reproduction. These traits make them susceptible to targeted and by‑catch fsheries and are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Multiple studies have examined fsheries impacts, but nursery areas or foraging neonate and juvenile concentrations have not been examined. This study describes the frst nursery area for M. munkiana at Espiritu Santo Archipelago, Mexico. We examined spatial use of a shallow bay during 22 consecutive months in relation to environmental patterns using traditional tagging (n = 95) and acoustic telemetry (n = 7). Neonates and juveniles comprised 84% of tagged individuals and their residency index was signifcantly greater inside than outside the bay; spending a maximum of 145 consecutive days within the bay. Observations of near‑term pregnant females, mating behavior, and neonates indicate an April to June pupping period. Anecdotal photograph review indicated that the nursery area is used by neonates and juveniles across years. These fndings confrm, for the frst time, the existence of nursery areas for Munk’s pygmy devil rays and the potential importance of shallow bays during early life stages for the conservation of this species. Nursery areas have been shown to be important for many elasmobranch species 1,2. -

Devils in Distress: the Plight of Mobula Rays

CMS/Sharks/MOS2/Inf.14 Devils in Distress The Plight of Mobula Rays A school of Atlantic pygmy devil rays (Mobula hypostoma) off the Yucatán Peninsula in the Caribbean | Photo © Shawn Henrichs obula rays (Mobula spp.; Family: Mobulidae; commonly referred to as devil rays) are at great risk of severe global Mpopulation declines due to target and incidental fishing pressure1. Similar to the closely related and larger manta rays (Manta spp.)*, Mobula generally grow slowly, mature late, and produce few offspring over long lifetimes1,2. This life history strategy, coupled with their migratory nature and inherent schooling behaviour, makes these species extremely vulnerable to overexploitation. Escalating demand for dried Mobula gill plates for use in Chinese medicine, as well as meat and cartilage, has led to targeting of these vulnerable species through fisheries that are largely unregulated and unmonitored. Significant catch declines have been observed in a number of locations in the Indo-Pacific, Eastern Pacific, and Indian Ocean regions, often despite evidence of increased fishing effort. Population declines are likely occurring in other locations, but have gone unnoticed. Morphological similarities across the nine Mobula spp. and their traded gill plates, combined with overlapping geographic distributions, make species identification difficult. As a result, detailed reporting of catches from the vast majority of countries is lacking, presenting a challenge for population assessment. Measures to ensure sustainability of Mobula catch through fisheries management and international trade controls are also currently lacking. Change is needed now before overfishing leads to severe, perhaps irreparable depletion. Listing Mobula under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) is warranted to improve fisheries and trade data, establish science-based exports limits, bolster enforcement of national protections, and complement listing under the Convention on Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). -

MOBULA RAYS (GENUS Mobula) in CMS APPENDIX I and II

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.24.1.10/ MIGRATORY Rev.1 4 November 2014 SPECIES Original: English 11th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Quito, Ecuador, 4-9 November 2014 Agenda Item 24.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF ALL SPECIES OF MOBULA RAYS (GENUS Mobula) IN CMS APPENDIX I AND II Summary: The Government of Fiji has submitted a proposal for the inclusion of all species of Mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in CMS Appendix I and II at the 11th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP11), 4-9 November 2014, Quito, Ecuador. A revised proposal for the inclusion of all species of Mobula Rays (Mobula) in CMS Appendices I and II was subsequently submitted by Fiji pursuant to Rule 11 of the COP Rules of Procedure. The proposal is reproduced under this cover for a decision on its approval or rejection by the Conference of the Parties. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the Meeting. Delegates are requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.24.1.10/Rev.1: Proposal I/10 & II/11 PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL: Inclusion of mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in Appendix I and II B. PROPONENT: Government of Fiji C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT: 1. Taxon 1.1 Class: Chondrichthyes, subclass Elasmobranchii 1.2 Order: Rajiformes 1.3 Subfamily: Mobulinae 1.4 Genus and species: All nine species within the Genus Mobula (Rafinesque, 1810): Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788), Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908), Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, 1892), Mobula eregoodootenkee (Bleeker, 1859),Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula hypostoma (Bancroft, 1831), Mobula rochebrunei (Vaillant, 1879), Mobula munkiana (Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, 1987) and any other putative Mobula species. -

Phylogeny of the Manta and Devilrays (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae), with an Updated Taxonomic Arrangement for the Family

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2017, XX, 1–26. With 8 figures. Phylogeny of the manta and devilrays (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae), with an updated taxonomic arrangement for the family WILLIAM T. WHITE1,2*, SHANNON CORRIGAN3, LEI YANG3, AARON C. HENDERSON4, ADAM L. BAZINET5, DAVID L. SWOFFORD6 and GAVIN J. P. NAYLOR3,7 1CSIRO National Research Collections Australia – Australian National Fish Collection, Hobart, TAS 7000, Australia 2CSIRO Oceans & Atmosphere, Hobart, TAS 7000, Australia 3Department of Biology, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC 29401, USA 4Department of Natural Sciences, School of Science and Computing, Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, Dublin Road, Galway H91 T8NW, Ireland 5Laboratory of Molecular Evolution, Center for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA 6Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA 7Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Received 6 April 2016; revised 30 January 2017; accepted for publication 19 March 2017 DNA sequence data from mitochondrial genomes and c. 1000 nuclear exons were analysed for a complete taxon sampling of manta and devilrays (Mobulidae) to estimate a current molecular phylogeny for the family. The result- ing inferences were combined with morphological information to adopt an integrated approach to resolving the taxonomic arrangement of the family. The members of the genus Manta were found to consistently nest within the Mobula species and consequently the genus Manta is placed into the synonymy of Mobula. Mobula eregoodootenkee, M. japanica and M. rochebrunei were each found to be junior synonyms of M. kuhlii, M. mobular and M. hypostoma, respectively. The mitochondrial and nuclear tree topologies were in agreement except for the placement of M. -

The Shark and Ray Trade in Singapore

TRAFFIC THE SHARK AND RAY TRADE REPORT IN SINGAPORE MAY 2017 Boon Pei Ya TTRAFFIC-sg-sharkray-trade.pdfRAFFIC-sg-sharkray-trade.pdf ..pdfpdf 1 226/05/20176/05/2017 110:07:210:07:21 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Suite 12A-01, Level 12A, Tower 1, Wisma AmFirst, Jalan Stadium SS 7/15, 47301 Kelana Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2017. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-63-3 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Boon, P.Y. (2017). The Shark and Ray Trade in Singapore. TRAFFIC, Southeast Asia Regional Office, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Front cover photograph: Manta Ray. -

Mobulid Rays Reef Manta and Devil Rays

Fact sheet for the 11th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP11) to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) Mobulid Rays Reef Manta and Devil Rays Reef Manta Ray Manta alfredi Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula eregoodootenkee Giant Devil Ray Mobula mobular Shortfin Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii Spinetail Devil Ray Mobula japanica Atlantic Devil Ray Mobula hypostoma Bentfin Devil Ray Mobula thurstoni Lesser Guinean Devil Ray Mobula rochebrunei Chilean Devil Ray Mobula tarapacana Munk’s Devil Ray Mobula munkiana Proposed action Inclusion on CMS Appendices I & II Proponents Fiji YAP BARTOSZ CIEŚLAK/WIKIPEDIA COMMONS YAP Overview Manta and Devil Ray species (family Mobulidae) share an inherent vulnerability to overexploitation due to exceptionally low productivity and aggregating behavior. Around the world, these large, migratory rays are facing intense targeted and incidental fishing pressure, increasingly driven by escalating Chinese demand for their gill plates. This largely unregulated mortality risks population and ecosystem health, as well as threatening substantial revenue possible through tourism. Inclusion in CMS Appendices I & II is warranted to prevent long-standing depletion, bolster existing national safeguards, preserve economic and ecological benefits, and improve the understanding of species status. Such action will also complement the CMS Appendices I & II listing for the Giant Manta Ray (Manta birostris), and the listing of Manta species under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). SHARK ADVOCATES INTERNATIONAL Fact sheet for the 11th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP11) to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) Biology and Distribution and Northern Mariana Islands), and Australia (Christmas Mobulid rays occur in the world’s tropical and temperate Island and Cocos Keeling Islands). -

The Impact of the IOTC Fisheries on Mobulid Rays: Status and Interactions, Data Availability, and Recommendations for Management Lois Flounders 2

IOTC-2020-WPEB16-18 The impact of the IOTC fisheries on mobulid rays: status and interactions, data availability, and recommendations for management Lois Flounders 2 Executive Summary Introduction and status of mobulids Manta and devil rays (collectively known as mobulids) are a family of migratory elasmobranchs. Their life history traits mean the largest Mobula species have maximum rates of intrinsic population increase among the lowest of all elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al., 2014). Mobulids are vulnerable to both targeted fisheries and bycatch and are caught in both small-scale and commercial (e.g. tuna) fisheries (Croll et al., 2016). Such fisheries are a major threat to mobulids, with some populations exhibiting declines of over 90% (e.g. Lewis et al., 2015; Rohner et al., 2017; Moazzam, 2018). In the Indian Ocean, all mobulid species are assessed as either Vulnerable or Endangered (IUCN, 2020; Table 3.), with steep population declines due to exploitation in fisheries playing a major role in these assessments. In response to growing concern, in 2019 the IOTC adopted Resolution 19/03 on the conservation of mobulids caught in association with fisheries in the IOTC Area of Competence (Annex 1). Interactions with the IOTC fisheries Mobulids are mainly caught as bycatch, primarily in the industrial purse-seine fisheries, and to a lesser extent in longline fisheries (Croll et al., 2016; Shahid et al., 2018). They are also incidentally captured in small-scale gillnet fisheries, usually being retained for their meat and gill plates (White et al., 2006; Ardill et al., 2011; Moazzam, 2018). Mobulids are particularly susceptible to incidental catch in tuna fisheries due to their epipelagic distribution in regions of high productivity, leading to a high level of distributional overlap with target species (Croll et al., 2012).