Instructions to Prepare a Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian in Parole Del Cibo in Nord America

provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Università degli Studi di Udine View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Carla Marcato Italian in parole del cibo in Nord America Parole chiave: Italian, Angloamericano, Lessico gastronomico Abstract: In this article we consider the presence of the adjective “Italian” in the culinary vocabulary in the USA and Canada. We find the usage of this ethnic adjective in some common words that are used in cook books and menus, particularly in the menus of Italian restaurants. The terms with “Italian” demonstrate the influence of Italian food on the American one. Keywords: Italian, Anglo-American, Gastronomic lexicon Contenuto in: Nuovi valori dell'italianità nel mondo. Tra identità e imprenditorialità Curatori: Raffaella Bombi e Vincenzo Orioles Editore: Forum Luogo di pubblicazione: Udine Anno di pubblicazione: 2011 Collana: Convegni e incontri ISBN: 978-88-8420-726-5 ISBN: 978-88-8420-969-6 (versione digitale) Pagine: 157-164 Per citare: Carla Marcato, «Italian in parole del cibo in Nord America», in Raffaella Bombi e Vincenzo Orioles (a cura di), Nuovi valori dell'italianità nel mondo. Tra identità e imprenditorialità, Udine, Forum, 2011, pp. 157-164 Url: http://www.forumeditrice.it/percorsi/lingua-e-letteratura/convegni/nuovi-valori-dellitalianita-nel-mondo/italian-in- parole-del-cibo-in-nord-america FARE srl con socio unico Università di Udine Forum Editrice Universitaria Udinese via Larga, 38 - 33100 Udine Tel. 0432 26001 / Fax 0432 296756 / www.forumeditrice.it FARE srl con socio unico Università di Udine Forum Editrice Universitaria Udinese via Larga, 38 - 33100 Udine Tel. -

Class 1.3 Cheeses Consorzio Tutela Taleggio Via Roggia Vignola 9

ANNEX I SUMMARY TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR REGISTRATION OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS NAME OF THE GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION: TALEGGIO CATEGORY OF THE PRODUCT FOR WHICH THE NAME IS PROTECTED Class 1.3 Cheeses APPLICANT: Consorzio Tutela Taleggio Via Roggia Vignola 9 - 24047 Treviglio (BG) PROTECTION IN EU MEMBER STATE OF ORIGIN - Decreto del Presedente della Repubblica del 15.09.1988; - Regolamento (CE) n. 1107/96 della Commissione del 12 giugno 1996 relativo alla registrazione delle indicazioni geografiche e delle denominazioni di origine nel quadro della procedura di cui all'articolo 17 del regolamento (CEE) n. 2081/92 del Consiglio DESCRIPTION OF THE AGRICULTURAL PRODUCT OR FOODSTUFF Soft raw table cheese made only with whole cow’s milk. The physical characteristics of the TALEGGIO cheese are as follows: 1) wheel: parallelepiped quadrangular. With sides from 18 to 20 cm; 2) heel: straight 4 / 7 cm with flat surfaces and sides of 18 / 20 cm; 3) average weight: from 1.7 to 2.2 kg per wheel, more or less, for both characteristics in relation to the technical processing conditions. At any rate, the variation cannot exceed 10% ; 4) rind : thin, soft consistency, natural rose colour (l 77 a/b 0.2 at tristimulus colorimeter), with presence of typical microflora. No processing of the rind is allowed. 5) paste: cohesive structure; no holes with only a few extremely small ones irregularly distributed; basically compact consistency, softer right underneath the rind; 6) colour of the paste: from white to straw yellow; 7) taste: characteristic, slightly aromatic; 8) chemical characteristics: fat content per dry matter 48%; minimum dry extract 46% ; maximum water content 54%, furosine max 14mg/100g proteins. -

Tradizione Culinaria

Tradizione Culinaria in Val di Lima Agriturismo IL LAGO Tradizione Culinaria Prima di lasciarvi alla degustazione delle ricette che seguiranno, vorrei esprimere un particolare ringraziamento alle donne che con tanto amore e pazienza mi hanno accolto e fatto partecipe della loro giovinezza, trasmettendomi sensazioni così vivide che ora sembra di aver vissuto e visto con i miei occhi quei tempi, assaporando odori e sapori che con tanta maestria mi hanno descritto. Vorrei anche ricordare i loro nomi: Gemma, Nilda, Sabina, e due cari “nonni” che ora non sono più tra noi, Dina e Attilio, che per primi ci hanno accolti come figli facendoci conoscere ed apprezzare le bellezze di questi luoghi. Infine un ringraziamento agli amici di Livorno che con me hanno accettato la scommessa di una vita vissuta nel rispetto della natura e dell’uomo, alla ricerca della memoria e dell’essenza della libertà, per un futuro migliore. Maria Annunziata Bizzarri Agrilago Azienda Agricola - Agrituristica IL LAGO via di Castello - Casoli Val di Lima 55022 Bagni di Lucca (LU) tel. 0583.809358 fax 0583.809330 Cell. 335.1027825 www.agrilago.it [email protected] Testi tratti da una ricerca di: Maria Annunziata Bizzarri 1 Tradizione Culinaria UN PO’ DI STORIA A Casoli, nella ridente Val di Lima, ogni famiglia aveva un metato che poteva far parte della casa o essere nelle immediate vicinanze o nella selva. Nel metato venivano seccate le castagne che avrebbero costituito il sostentamento per l’intero anno e rappresentato una merce di scambio per l’acquisto dei generi alimentari non prodotti direttamente, come il sale e lo zucchero. -

CHICKEN 14 Your Choice of Piccata . Marsala . Or Francaise Served with Vegetable of the Day & Fingerling Potatoes

CLAMS POSILLIPO 12 CLASSIC CAESAR 10 steamed middle neck clams with anchovy dressing . croutons garlic . evoo . wine CAPRESE 10 BRUSCHETTA CLASICA 6 GARLIC CHEESE BREAD 6 fior di latte mozzarella . sliced vine ripe grilled Tuscan style bread with vine served with whipped ricotta tomatoes . evoo . basil, balsamic glaze ripe tomatoes, basil, evoo, topped with basil and fresh mozzarella ASSORTED OLIVES 6 CHOPPED ANTIPASTO 1 0 cerignola olives, gaeta olives, crisp romaine . salami . italian cheeses . HOUSE MADE MEATBALLS 8 olives . tomato . onions . cucumber (2) all beef meatballs simmered in PIATTO DI PROSCIUTTO TUSCANO 6 tomato gravy topped with whipped roasted peppers . chick peas, roasted garlic red wine vinaigrette ricotta PIATTO DI SALAMI 6 CALAMARI FRITTI 10 fiocchetti ROASTED BEET SALAD 10 garlic lemon aioli and marinara arugula . red wine vinaigrette . PIATTO DI PARMIGIANO 6 goat cheese . red onion . Served with organic honey, 12 month aged dried figs MISTA SALAD 6 mixed greens, tomatoes, onions, ARTHUR AVE CLASSIC 12 carrots,cucumbers & balsamic mozzarella . tomato . oregano . parmigiana PESTO 12 pesto . fontina . pancetta . parmigiana SPAGHETTI & MEATBALLS POMAROLA 14 QUATTRO FORMAGGIO 12 fresh tomato sauce with basil and garlic and (2) meatballs fontina . mozzarella . ricotta . parmigiana . “no tomato”” ORECCHIETTE ABRUZZI 14 MARGHERITA 12 Broccoli rabe, evoo, garlic, sausage crushed d.o.p. tomatoes . fior de latte . evoo . basil SPAGHETTI ALA SCOGLIO 18 VERDURA 11 sautéed middle neck clams, mussels, and shrimp in a white wine garlic over spaghetti bianco with mixed grilled & roasted seasonal vegetables MEZZO RIGATONI BOSCAIOLO 14 PROSCUITTO & ARUGULA 14 sausage, mushroom, touch of cream mozzarella . marinara. fresh arugula . prosciutto and parmigiana ADD ONS GNOCCHI DI RICCOTTA 15 meat toppings 2 Italian sausage . -

Cheeses Part 2

Ref. Ares(2013)3642812 - 05/12/2013 VI/1551/95T Rev. 1 (PMON\EN\0054,wpd\l) Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92 APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION: Art. 5 ( ) Art. 17 (X) PDO(X) PGI ( ) National application No 1. Responsible department in the Member State: I.N.D.O. - FOOD POLICY DIRECTORATE - FOOD SECRETARIAT OF THE MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FISHERIES AND FOOD Address/ Dulcinea, 4, 28020 Madrid, Spain Tel. 347.19.67 Fax. 534.76.98 2. Applicant group: (a) Name: Consejo Regulador de la D.O. "IDIAZÁBAL" [Designation of Origin Regulating Body] (b) Address: Granja Modelo Arkaute - Apartado 46 - 01192 Arkaute (Álava), Spain (c) Composition: producer/processor ( X ) other ( ) 3. Name of product: "Queso Idiazábaľ [Idiazábal Cheese] 4. Type of product: (see list) Cheese - Class 1.3 5. Specification: (summary of Article 4) (a) Name: (see 3) "Idiazábal" Designation of Origin (b) Description: Full-fat, matured cheese, cured to half-cured; cylindrical with noticeably flat faces; hard rind and compact paste; weight 1-3 kg. (c) Geographical area: The production and processing areas consist of the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country and part of the Autonomous Community of Navarre. (d) Evidence: Milk with the characteristics described in Articles 5 and 6 from farms registered with the Regulating Body and situated in the production area; the raw material,processing and production are carried out in registered factories under Regulating Body control; the product goes on the market certified and guaranteed by the Regulating Body. (e) Method of production: Milk from "Lacha" and "Carranzana" ewes. Coagulation with rennet at a temperature of 28-32 °C; brine or dry salting; matured for at least 60 days. -

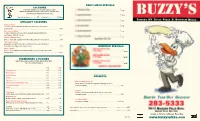

Buzzy Menu 2018.Indd

DAILY LUNCH SPECIALS CALZONES Big on taste and big in size, our basic calzone is stuffed 4.95 with Ricotta and Mozzarella Cheeses and baked for a pleasing crunch. Served with a side of Homemade Tomato Sauce. 10.75 Basic Cheese Calzone . .7.50 or Stuff it for. .95 an item 8.25 SPECIALTY CALZONES Angelo’s Favorite Our cheese calzone stuffed with Sliced Tomatoes, Black Olives, Green Peppers 7.95 and Mushrooms . 10.75 Lou’s Classic Calzone 8.25 A classic combination, our cheese calzone fi lled with Pepperoni, Mushrooms, Green Peppers, and Italian Sausage . 10.75 Dominic’s Meaty Calzone 7.95 A cheese calzone with a hearty portion of Bacon Ham and Pepperoni baked inside. 9.95 “Big” Tony’s Calzone Mozzarella, Ricotta and Romano Cheeses smothered with seasoned Ground Beef, Black Olives, Green Peppers and Cheddar Cheese . 11.95 EVERYDAY SPECIALS Vince’s Calzone A cheese calzone stuffed with Homemade Meatballs, Hot Cherry Peppers, Mushrooms, 30.95 and Black Olives . 10.75 48.75 SUBMARINES & HOAGIES Subs include Cheese, Lettuce, Tomato, Onions, Oil or Mayo. Rolls Toasted Upon Request. 19.95 Full Half Steak & Cheese. 9.25 . .6.25 Ham & Cheese. 9.25 . .6.25 Italian Sausage . 9.25 . .6.25 DESSERTS Salami . 9.25 . .6.25 Capocollo. 9.25 . .6.25 New York Style Cheescake Assorted (Ham, Salami Capocollo) . 9.25 . .6.25 A Rich, elegant Cheesecake served plain or with Raspberry, Carmel Chicken Finger Sub . .9.25 . .6.25 or Chocolate topping . 3.95 Turkey . .9.25 . .6.25 Tiramisu Steak Hoagy A traditional Italian dessert made with Mascarpone cream cheese Tender ribeye steak, melted cheese, fried onions & mushrooms. -

Insalatee Zuppe Pizze Calzone Extras Build Your Own Pizza

PIZZE GLUTEN-FREE DOUGH available; add $3.00 01 MARGHERITA Marinara sauce, mozzarella, fresh basil. 8.50 02 PEPPERONI Pepperoni, marinara sauce, mozzarella, fresh oregano. 8.95 03 MOTORINO INSALATE E ZUPPE PIADINE Folded flatbread sandwiches Alfredo sauce, spinach, artichoke hearts, oven roasted tomatoes, balsamic onions, pesto drizzle. 10.95 31 DELLA CASA 23 HERO 04 POLLO E PUMANTE Romaine, asiago, tomatoes, choice of house vinaigrette, Hard salami, capocollo ham, dijon mayonnaise, vinaigrette, mozzarella, Roasted chicken, garlic oil, asiago, mozzarella, sun-dried tomatoes, creamy parmesan, or balsamic vinaigrette. 4.95 provolone, parmesan, tomatoes, pepperoncini, red onions, romaine, roasted red peppers, fresh basil. 10.75 fresh oregano. 10.75 32 IL VICINO 05 TESTAROSSA Romaine, roasted chicken, hard boiled egg, house vinaigrette, 24 VESPA Pepperoni, marinara sauce, mozzarella, roasted red peppers, gorgonzola, tomatoes, artichoke hearts, walnuts. Roasted chicken, sun-dried tomato mayonnaise, pesto dressing, fontina, kalamata olives, caramelized onions, mushrooms, fresh oregano. 9.95 parmesan, tomatoes, spinach, fresh oregano. 10.25 Small 8.95 | Large 11.95 06 SALSICCIA 33 CAESAR 25 MEDITERRANEO Pepperoni, house-made sausage, marinara sauce, mozzarella, tomatoes, Romaine, Spanish white anchovy, house-made creamy caesar Light albacore tuna salad (dolphin safe), capers, sun-dried tomato mayonnaise, fresh oregano. 10.50 parmesan, red onion, tomato, romaine, fresh oregano. 11.50 dressing, asiago, ciabatta croutons. 07 RUSTICA Small 6.75 | Large 8.95 | With roasted chicken add 2.00 Marinara sauce, mozzarella, artichoke hearts, kalamata olives, 34 SPINACI PASTA AL FORNO roasted garlic, capers, fresh oregano. 10.25 Fresh spinach, pesto dressing, gorgonzola, roasted red peppers, 08 ANGELI pine nuts, red onions. -

Clean Label Alternatives in Meat Products

foods Review Clean Label Alternatives in Meat Products Gonzalo Delgado-Pando 1 , Sotirios I. Ekonomou 2 , Alexandros C. Stratakos 2 and Tatiana Pintado 1,* 1 Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition (CSIC), José Antonio Novais 10, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 2 Centre for Research in Biosciences, Coldharbour Lane, Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences, University of the West of England, Bristol BS16 1QY, UK; [email protected] (S.I.E.); [email protected] (A.C.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Food authorities have not yet provided a definition for the term “clean label”. However, food producers and consumers frequently use this terminology for food products with few and recognisable ingredients. The meat industry faces important challenges in the development of clean-label meat products, as these contain an important number of functional additives. Nitrites are an essential additive that acts as an antimicrobial and antioxidant in several meat products, making it difficult to find a clean-label alternative with all functionalities. Another important additive not complying with the clean-label requirements are phosphates. Phosphates are essential for the correct development of texture and sensory properties in several meat products. In this review, we address the potential clean-label alternatives to the most common additives in meat products, including antimicrobials, antioxidants, texturisers and colours. Some novel technologies applied for the development of clean label meat products are also covered. Keywords: clean label; meat products; nitrites alternatives; phosphates alternatives Citation: Delgado-Pando, G.; Ekonomou, S.I.; Stratakos, A.C.; Pintado, T. -

Touchofitaly.Com (302) 703-3090

PRIMI PIATTI SECONDI PIATTI Orecchiette con Salsiccia e Friarielli 18 Pollo al Taleggio 21 Ear shaped pasta with Italian sausage and broccoli rabe sautéed in Chicken cutlet breaded in our homemade bread crumbs, pan-seared in garlic, and EVOO a white wine Italian herb sauce then topped with melted taleggio cheese and prosciutto di parma, served over a bed of sautéed spinach Ravioli 18 Borgatti’s hand-crafted cheese ravioli topped with our homemade Salmone Oreganata 21 tomato basil sauce and a dollop of fresh ricotta Salmon roasted in our wood-fired oven then topped with warm caponata, served with escarole and cannellini beans Fettuccine Alfredo 18 Filetto di Manzo alla Griglia 28 Homemade fettuccini pasta tossed in a light parmigiano reggiano Fire-grilled hanger steak with Italian seasonings served with sautéed cream sauce topped with seared pancetta and shaved asiago cheese peppers, onions, and broccoli rabe Costoletta di Vitello 30 Garganelli alla Bolognese 19 Porterhouse veal chop roasted to a medium temperature in our wood- Homemade penne style pasta tossed in our classic meat sauce topped fired oven, seasoned with Italian herbs and EVOO, served with spinach with freshly grated parmigiano reggiano and basil and rosemary roasted potatoes Tagliatelle Fra’ diavolo 24 Pollo alla Contadina 23 Thin flat noodles with shrimp, clams, mussels, and calamari tossed Oven roasted chicken on the bone with sweet Italian sausage sautéed in a spicy hot marinara sauce with peppers, onions, potatoes, EVOO, and rosemary Gnocchi Calciano 14 Light as a feather -

APPET SOUP & SA Antipasti CHEESE Cured MEATS IZERS

Call: 720.484.5484 1801 Central Street • Denver, Colorado 80211 PASTA ANTIPASTI APPETIZERSmarcellasrestaurant.com 3 for 1 8 • 5 for 24 PARMA PROSCIUTTO Whipped Ricotta Cheese, MAKE A RESERVATION 11 PENNE ALLA Spicy Tomato Sauce, BRUSCHETTA Roasted Tomato SICILIAN CAPONATA ROASTED ARRABIATTA Toasted Garlic, Sweet Basil 15.50 Roasted Eggplant Salad, CAULIFLOWER MELTED Crostini, Apple, 13 Olives, Capers Olive, EVOO PECORINOAPPETIZERS CHEESE Truffle Honey RAVIOPALI GoatS CheeseTA Ravioli, Roasted ANTIPASTI MEZZALUNA Eggplant, Tomato, Basil 17.50 WARM OLIVES3 for 1 8 • 5 ZforUCCHINI 24 PARMESAN BPARAISEDRMA P R OSCIUTTO Whipped Ricotta Cheese, Cerignola, Picholine, Roasted Garlic Simple Tomato Sauce 1011 FETTUCPENNEC INEALLA & TornSpicy BreadTomato Crumb, Sauce, SICILIAN CAPONATA ROASTED VBREAUSCHETTAL MEATBALL Roasted Tomato Gaeta, Beldi & Chiles ARRMEATABIATTABALL Alfredo,Toasted TomatoGarlic, Sweet Marinara Basil 17 15.50 Roasted Eggplant Salad, CAULIFLOWER PMREOSCIUTTOLTED ShavedCrostini, Prosciutto, Apple, 13 FOlives,UNGHI Capers MISTI GRAOlive,PPA EVOOCUR ED ANDPECO MERINOLON CHEESE RipeTruffle Melon Honey 10 PIZZA FAVORITES SPAGHETTIRAVIO L&I TomatoGoat Cheese Marinara, Ravioli, Roasted Mixed Mushrooms, SALMON MEZZALUNA Eggplant, Tomato, Basil 17.50 ZUCCHINI PARMESAN MEATBALL Fresh Grated Parmesan 17 Shiitake,WARM O Crimini,LIVES Cucumber, Red Onion, BRAISED Roasted Garlic ARANCINI SimpleFried Risotto, Tomato Mozzarella Sauce 10 Cerignola,Oyster Picholine, Lemon Zest VEAL MEATBALL FETTUCCAPELLCINIINE A &L BlisteredTorn Bread Tomato, -

Classic Pizza Tasting Pizza in Teglia Pizza Our Tasting Menu

TO START Arancino - fried Sicilian rice ball with ragout and provola cheese • 3 € f.u. Fried Pizzina with Parma ham and burrata • 3 € f.u. Potato chips, light but flavorful • 5 Potato croquettes • 3 € f.u. Fried Pizzina “Montanara” with tomato and Grana cheese • 3 € f.u. Pizzella with aubergines • 3 € f.u. Mini fried Calzone with tomato, fiordilatte and basil • 3 € f.u. • Limousine Burger • 15 • Fried calamari* • 15 200 gr. limousine beef, lettuce, tomato, guacamole and Fontina cheese • Fried calamari* and shrimps* • 18 For our dough we use blend of wholemeal and semi-whole flour. We suggest the sharing. CLASSIC PIZZA TASTING PIZZA MARINARA • 8 BURRATA AND TOMATO • 14 MARGHERITA WITH FIORDILATTE • 10 BUFALA AND TOMATO • 14 MARGHERITA WITH BUFALA • 10 PARMA HAM AND BURRATA • 20 COSACCA • 10 CARAMELIZED ONION taleggio cheese • 18 tomato, Provolone del Monaco cheese and basil Barley dough RED SHRIMP* burrata, artichokes and hazelnuts • 28 SALINA CAPER AND CETARA ANCHOVY • 13 CULATELLO DI ZIBELLO spaccatelle and figs molasse • 27 tomato, fiordilatte and oregano AMBERJACK CARPACCIO* CASCINA • 14 crispy “Cru Caviar”, onion and persimmon • 26 bufala, raw cherry tomatoes, fresh salad and Parma ham MADNESS • 14 bufala, cherry tomatoes, Grana, basil and Parma ham IN TEGLIA PIZZA NDUJA FROM SPILINGA • 16 fiordilatte, persimmon, bufala ricotta cheese and caramelized onions Barley dough CHICORY AND ANCHOVY • 16 PARMA HAM AND BURRATA • 12 bufala, chicory, marinated anchovy sauce, confit cherry tomatoes and chili pepper Barley dough ARTISAN COOKED HAM -

Vin En Amphore Coups De Cœur Vins Oranges

VIN EN AMPHORE COUPS DE CŒUR ❤ VINS ORANGES � VINS AU VERRE (cl.10) BOLLICINE Champagne BdB Grand Cru Cramant, D.Grellet CHAMPAGNE CHF 18 Prosecco, Casa Coste Piane VENETO CHF 9 VINI BIANCHI Pinot Grigio, Meran ALTO ADIGE 2019 CHF 9 Trebbiano, Edoardo Sderci TOSCANA 2019 CHF 8 Fiano Irpinia, Picariello CAMPANIA 2018 CHF 10 Chardonnay Lices en Peria, Aigle 2 têtes JURA 2015 CHF 10 Rosé Maggese, TOSCANA 2019 CHF 8 VINS DE MACERATION ET ORANGES Malvasia, Le Nuvole BASILICATA 2018 CHF 10 Bianco alla Marta, Buondonno � TOSCANA 2017 CHF 7 VINI ROSSI Nero D’Avola Turi, Salvatore Marino SICILIA 2019 CHF 8 Sangiovese La Gioia, Riecine TOSCANA 2014 CHF 13 Cabernet Riserva, Renato Keber FRIULI 2010 CHF 12 Barbera/Dolcetto Onde Gr., Fabio Gea PIEMONTE 2017 CHF 14 Barolo, Casina Bric PIEMONTE 2013 CHF 16 VINI DESSERT (cl.6) Moscato di Noto, Marabino SICILIA 2016 CHF 10 VINS D’EXCEPTION AU VERRE CORAVIN (cl.10) VINI BIANCHI Friulano Riserva,RENATO KEBER FRIULI 2005 CHF 15 Pinot Bianco, RENATO KEBER FRIULI 2004 CHF 19 Chardonnay Riserva, RENATO KEBER FRIULI 2003 CHF 20 Verdicchio Riserva Il San Lorenzo MARCHE 2004 CHF 26 VINI ROSSI Langhe Rosso, San Fereolo PIEMONTE 2006 CHF 15 Testamatta, Bibi Graetz 98 Pt. RP JS TOSCANA 2013 CHF 35 Chianti Classico GRAN SELEZIONE, Candialle TOSCANA 2013 CHF 23 Amarone, Monte dei Ragni VENETO 2012 CHF 35 Merlot Tresette, Riecine TOSCANA 2016 CHF 20 CHAMPAGNE 2/3 CEPAGES LE MONT BENOIT EMMANUEL BROCHET CHF 140 3C TROIS CEPAGES BOURGEOIS DIAZ CHF 120 CUVEE « N » BOURGEOIS DIAZ CHF 130 CHAMPAGNE CHARDONNAY BLANC D’ARGILLE