Tracing Walfridus – a Quest for the Sound of a Past Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter to the House of Representatives About Extraction

> Retouradres Postbus 20401 2500 EK Den Haag Directoraat-generaal Energie, Telecom & President of the House of Representatives Mededinging of the States General Directie Energiemarkt Binnenhof 4 Bezoekadres 2513 AA THE HAGUE Bezuidenhoutseweg 73 2594 AC Den Haag Postadres Postbus 20401 2500 EK Den Haag Factuuradres Postbus 16180 2500 BD Den Haag Overheidsidentificatienr 00000001003214369000 Datum T 070 379 8911 (algemeen) Betreft Extraction decree of gas extraction in The Groningen field and reinforcement measurements. www.rijksoverheid.nl/ez Ons kenmerk DGETM-EM / 14207601 Dear President, Uw kenmerk The consequences of years of gas extraction in Groningen are becoming increasingly clear. The number of earthquakes recorded in 2012, 2013 and 2014 Bijlage(n) (until 9 December) were 93, 119 and 77 respectively. In the same period there were a total of 20, 29 and 18 tremors respectively that measured more than 1.5 on the Richter scale. It is anticipated that the strength and frequency of the earthquakes will increase over the coming years. The consequences for houses, monuments and other buildings are plain to see. The Groningen field lies in the municipalities of Appingedam, Bedum, Bellingwedde, Delfzijl, Eemsmond, Groningen, Haren, Hoogezand-Sappemeer, Loppersum, Menterwolde, Oldambt, Pekela, Slochteren, Ten Boer and Veendam. The sense of having a safe living environment has been eroded in the area where there are (frequent) earthquakes. This deeply affects the daily life of the residents. At the same time, gas extraction is essential to our energy supply in the Netherlands. The great majority of Dutch households use Groningen gas for their heating and cooking. Gas extraction is also an important source of revenue for the Dutch state. -

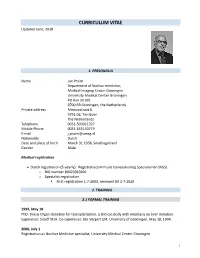

Curriculum Vitae Jan Pruim

CURRICULUM VITAE Updated June, 2018 1. PERSONALIA Name Jan Pruim Department of Nuclear medicine, Medical Imaging Center Groningen University Medical Center Groningen PO Box 30.001 9700 RB Groningen, the Netherlands Private address Meeuwstraat 8 9791 GE Ten Boer The Netherlands Telephone 0031-503021327 Mobile Phone 0031-655150779 E-mail [email protected] Nationality Dutch Date and place of birth March 31 1958, Smallingerland Gender Male Medical registration • Dutch registration (5-yearly): Registratiecommissie Geneeskundig Specialismen (RGS) o BIG number 89023363901 o Specialist registration § First registration 1-7-2000, renewed till 1-7-2020 2. TRAINING 2.1 FORMAL TRAINING 1994, May 18 PhD- thesis Organ donation for transplantation: a clinical study with emphasis on liver donation. Supervisor: Slooff MJH. Co-supervisor: ten Vergert EM. University of Groningen, May 18, 1994. 2000, July 1 Registration as Nuclear Medicine specialist, University Medical Center Groningen 1 1997 Certificate in Radiation Protection, University of Groningen 1976-1985 MD, University of Groningen, The Netherlands 1976 High School, Graduation Atheneum-B, Ichthus College, Drachten, The Netherlands 2.2 COURSES AND CERTIFICATES - Continuing education (last 5 year) Professionally Participation in national and international congresses, e.g. Radiological Society of North-America (RSNA), Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI), European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM), World Federation of Nuclear Medicine and Biology (WFNMB) and Scientific Meetings -

Northeast Groningen Confronting the Impact of Induced Earthquakes, Netherlands

Resituating the Local in Cohesion and Territorial Development House in Bedum, damaged by earthquakes (Photo: © Huisman Media). Case Study Report Northeast Groningen Confronting the Impact of Induced Earthquakes, Netherlands Authors: Jan Jacob Trip and Arie Romein, Faculty of Architecture and the Built En- vironment, Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands Report Information Title: Case Study Report: Northeast Groningen. Confronting the Impact of Induced Earthquakes, Netherlands (RELOCAL De- liverable 6.2) Authors: Jan Jacob Trip and Arie Romein Version: Final Date of Publication: 29.03.2019 Dissemination level: Public Project Information Project Acronym RELOCAL Project Full title: Resituating the Local in Cohesion and Territorial Develop- ment Grant Agreement: 727097 Project Duration: 48 months Project coordinator: UEF Bibliographic Information Trip JJ and Romein A (2019) Northeast Groningen. Confronting the Impact of Induced Earthquakes, Netherlands. RELOCAL Case Study N° 19/33. Joensuu: University of Eastern Finland. Information may be quoted provided the source is stated accurately and clearly. Reproduction for own/internal use is permitted. This paper can be downloaded from our website: https://relocal.eu i Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................. iii List of Tables .................................................................................................................... iii Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. -

MASTER THESIS Policies Against Urban Sprawl in the Changing Dutch

MASTER THESIS Policies against urban sprawl in the changing Dutch planning context Groningen case: from a monocentric compact city policy towards a new urbanisation path between intensification and expansion By: FRANCOIS PIRART Supervisors : Dr. Justin R. Beaumont Prof.dr. Jos Arts Master in Environmental and Infrastructure Planning Faculty of Spatial Sciences University of Groningen 2008 2 i Acknowledgements Many people have influenced and helped me in this master thesis. My thanks truthfully go to all of them who shared their ideas, responded to my questions and helped me to go in the right direction. In particular, I would like to mention my supervisor Justin Beaumont who pushed me forwards throughout the year, while at the same time leaving me enough space to find my own path. My thanks also go to Gerard Tolner, Laurens Huis in 't Veld, Frans Spakman, Hero Havenga, Martin Elfrink and Hans Westra - the local planners that accepted to be interviewed and to share their knowledge with me. They not only responded honestly to my questions, but also helped me to refine the scope and the questions of this master thesis. In particular, I am grateful towards Mr Tolner that continued to send me insights and thoughts connected to my research by emails during all this year (almost weekly!). Also, this master thesis would not have been possible without the professional help of Jozef Van Genk from the municipality of Groningen. I will never forget his sympathy and his unalterable desire to help me in my research. His interest and creativity brought me a lot. Last but not least, my appreciation goes to my family and friends, who I left one year in Belgium to come study in Groningen. -

Public Transportation “Made by OV- Bureau” How Do We Do It ?

Public Transportation “Made by OV- bureau” How do we do it ? London 2017, June 8th ir. Erwin Stoker Manager PT development Outline Introduction • Public transportation in the Netherlands • Public transportation in Groningen Drenthe • Franchising history Cases 1. Joint development and business cases 2. Buses 3. Bus depots 4. Personnel 5. Concession Management 6. OV-chipcard and national datawarehouse public transportation I won’t bite ! Concession = Franchise Public transportation in the Netherlands PT in the Netherlands National railways (Main network) Operator: - NS Nederlandse Spoorwegen - 100% public company - Negotiated contract 2015-2025 - Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment Tracks: - Prorail - 100% public company - Negotiated contract 2015-2025 - Maintenance and extensions - Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment PT in the Netherlands: Regional PT 14 responsible public bodies - 12 provinces - Rotterdam/The Hague - Amsterdam Modes: - Regional rail - Metro - Tram - Bus Responsible for tracks/road: - Local or regional road administration Wet Personenvervoer 2000 (PT bill 2000) - Privatisation of (former) provincial and city public transport (bus) companies - Obligation for PTA to franchise all public transportation from 2000 - Exclusive right for 1 operator in a certain area or on a certain line PT in the Netherlands: PT franchises (2017) All bus contracts franchised (Except Rotterdam/The Hague and Amsterdam: negotiated contract) Public transportation in Groningen and Drenthe Population Groningen 570.000 (City of Groningen -

Erwin Stoker Program Manager PT Development Public Transport Authority Groningen and Drenthe

Erwin Stoker Program Manager PT Development Public Transport Authority Groningen and Drenthe PT bus contracts 5.600 km2 PT Operator € 114,5 mln > 1 mln inhabitants Per year (Groningen 220.000) € 57 mln.€ 57,5 mln. subsidies passenger Groningen revenues Groningen 90 km Passengers Passenger kilometers 27 mln 290 mln per year per year Assen 360 buses Drenthe CO2 emissions (2017) Emmen 70 km 113 grams per passenger kilometer ZE Strategy: different solutions naar Borkum Schiermonnikoog Eemshaven Roodeschool Lauwersoog Uithuizen Usquert Warffum Eenrum Leens Baflo Ulrum Middelstum Delfzijl Zoutkamp Winsum Stedum Loppersum ‘motorwaybus’ Appingedam Bedum Sauwerd Ten Boer ? (Hydrogen?)600-800 km/day Buitenpost Wagenborgen Siddeburen Grijpskerk Zuidhorn Groningen 60 km/h Slochteren Qliner Grootegast Hoogkerk Harkstede Nieuweschans Leeuwarden Surhuisterveen Haren Leek Scheemda HOV ‘BRT’ Zuidbroek Eelde- Hoogezand- Paterswolde Sappemeer Winschoten Marum Roden Bellingwedde Snelweg en stad Drachten Veendam Zuidlaren Pekela’s Electric Vries 400-600 km/day Haulerwijk Norg Annen Vlagtwedde Q-link 35 km/h Gieten Oosterwolde Assen Stadskanaal Appelscha Heerenveen Smilde Musselkanaal Regional bus Borger 250-500 km/day Exloo Ter Apel ? (Hydrogen/electric?) Beilen 30km/h Westerbork Diever Dwingeloo Emmen Regional regional Zweeloo Steenwijk Sleen Netwerkvisie OV Groningen, Ruinen Groningen Drenthe Klazienaveen Nieuw-Amsterdam and Augustus 2015 Hoogeveen Assen, Emmen Dalen Meppel Electric Zuidwolde Coevorden Schoonebeek 150-300 km/day Legenda City city 18 km/h -

Fault Reactivation Mechanisms and Dynamic Rupture Modelling of Depletion-Induced Seismic Events in a Rotliegend Gas Reservoir

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw |96 – 5 | s131–s148 | 2017 doi:10.1017/njg.2017.27 Fault reactivation mechanisms and dynamic rupture modelling of depletion-induced seismic events in a Rotliegend gas reservoir Loes Buijze1,3,∗, Peter A.J. van den Bogert2, Brecht B.T. Wassing1, Bogdan Orlic1 &Johanten Veen1 1 Applied Geosciences, TNO, Princetonlaan 6, 3584 CB Utrecht, the Netherlands 2 Shell Global Solutions BV, Kessler Park 1 (At-126L), 2288 GS Rijswijk (ZH), the Netherlands 3 HPT Laboratory, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University. Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CB, Utrecht, the Netherlands ∗ Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 6 February 2017, accepted: 11 September 2017 Abstract Understanding the mechanisms and key parameters controlling depletion-induced seismicity is key for seismic hazard analyses and the design of mitigation measures. In this paper a methodology is presented to model in 2D the static stress development on faults offsetting depleting reservoir compartments, reactivation of the fault, nucleation of seismic instability, and the subsequent fully dynamic rupture including seismic fault rupture and near-field wave propagation. Slip-dependent reduction of the fault’s strength (cohesion and friction) was used to model the development ofthe instability and seismic rupture. The inclusion of the dynamic calculation allows for a closer comparison to field observables such as borehole seismic data compared to traditional static geomechanical models. We applied this model procedure to a fault and stratigraphy typical for the Groningen field, and compared the results for an offset fault to a fault without offset. A non-zero offset on the fault strongly influenced the stress distribution along the fault due to stress concentrations in the near-fault area close to the top of the hanging wall and the base of the footwall. -

Uitkomsten Der Achtste Tienjaarlpsctie Volkstelling

BIJDRAGEN TOT DE STATISTIEK VAN NEDERLAND. Uitgegeven door het Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. NIEUWE VOLGREEKS Mo. 3. Uitkomsten der achtste tienjaarlpsctie Volkstelling IN HET KONINKRIJK DER NEDERLANDEN GEHOUDEN OP DEN EEN EN DERTIGSTEN DECEMBER 1899. (met uitzondering van de beroepstelling en de woningstatistielc). NEGENDE DEEL. Provincie Groningen. Résultats du huitième recensement de la population du Royaume des Pays-Bas au 31 Décembre 1899. (à l'exception du dénombrement professionnel et de la statistique des habitations). IX. Province de Grom'ngue. 'S-GBAVENHAGE, ÖBBES. BELINPANÏE 1901. INHOUD. Algemeen overzicht blz. 1—2 Ie gedeelte: Plaatselijke iudeeliug. Bewoonde en onbewoonde huizen, bewoonde schepen en wagens „ 'A—48 2'- „ ludeeling der werkelijke bevolking naar de wijze van samenwoning on de samenstelling der gezins- (respectievelijk gestichts-) bevolking. „ 49—'54 ?ie „ Indeeling der werkelijke bevolking naar de geboorteplaats en de nationaliteit , 55—60 4C' „ Indeeling der werkelijke bevolking naar den leeftijd en den burger- lijken staat . 61 —146 5e „ Indeeling der werkelijlce bevolking naar de kerkelijke gezindten en den leeftijd , 147—180 TABLE DES MATIÈRES. Aperçu général pag. 1—2 ll'B partie : Division des communes. Maisons habitées et inhabitées, navires habités et chariots nomades „ 8—48 2llt' „ Répartition de la population de fait d'après la cohabitation et la com- position des familles (resp. de la population vivant dans des établissements). „ 49—54 3mu „ Répartition de la population de fait d'après le lieu de naissance et la nationalité , 55—60 4me „ Répartition de k population de fait d'après l'âge et l'état crvil ... „ 61—146 5me „ Répartition de la population de fait d'après les cultes et les groupes d'âge. -

OV-Bureau: Ontwerp Hoofdlijnen Dienstregeling Bus 2021 (Zienswijze)

Onderwerp OV-bureau: ontwerp hoofdlijnen dienstregeling bus 2021 (zienswijze) Steller Menno Oedekerk De leden van de raad van de gemeente Groningen te GRONINGEN Ons Telefoon 06 - 5277 4743 Bijlage(n) 1 kenmerk Uw brief Datum van Uw kenmerk - Geachte heer, mevrouw, Hierbij bieden wij u de door het dagelijks bestuur van het OV-bureau vastgestelde ontwerp hoofdlijnen dienstregeling bus 2021 aan. Met deze brief willen wij u in de gelegenheid stellen uw eventuele zienswijze op de ontwerp hoofdlijnen dienstregeling bus 2021 te geven. Hoofdlijnen dienstregeling busconcessie Groningen Drenthe 2021 Zoals wij onder andere in onze brief aan u over de ontwerpbegroting OV- bureau 2021 van 20 april jongstleden hebben laten weten staat de betaalbaarheid van het openbaar busvervoer onder druk. In de begroting OV- bureau 2021 en in de begrotingsjaren die daarop volgen, zal gezocht moeten worden naar structurele financiële oplossingen. Daarbij stellen wij ons ook de opdracht om met de mobiliteitsvisie mogelijke oplossingen aan te dragen die de exploitatie van het openbaar vervoer structureel verbeteren. De dienstregeling van 2021 is ontwikkeld op basis van het door het dagelijks bestuur OV-bureau vastgestelde financiële uitgangspunt van neutraliteit. Een ander belangrijk uitgangspunt bij het opstellen van deze nieuwe dienstregeling is het stap voor stap verbeteren van het dienstregelingsmodel waarbij zoveel mogelijk wordt ingespeeld op actuele ontwikkelingen. Vooruitlopend op het vaststellen van de mobiliteitsvisie gemeente Groningen zijn er voorstellen opgenomen waar weinig discussie over wordt verwacht en die passen binnen de met u besproken concept OV-visie die als input dient voor de op te stellen mobiliteitsvisie. Het dagelijks bestuur van het OV- bureau Groningen heeft op 24 april jl. -

Royal Netherlands Meteorological Lnstitute Ministry of in Frastructure and Water Management

Royal Netherlands Meteorological lnstitute Ministry of in frastructure and Water Management > Return address PO Box 201 3730 AE De Bilt KNMI Visiting address Utrechtseweg 297 3731 GA De Bilt The Netherlands De Mijnraad PO Box 201 Dr. J.C. Verdaas, Voorzitter 3730 AE De Bilt The Netherlands P.O. Box 93144 T +31 302206911 2500 AC 's-Gravenhage telefax +31 302210407 www.knmi.nl Contact Prof. dr. L.G. Evers Date : June 19, 2018 Subject: Seismic Hazard Assessment of Production Scenarios in Groningen' Our reference KNMI-2018/1420 Your reference Dear Mr. Verdaas, 18072342 Overheidsidentificatienr: 00000001003214369000 With reference to the letter of Mr. E. Wiebes, Minister Economic Affairs and Climate Enclosure(s) Policy, dated April 20, 2018 we hereby send you the report "Seismic Hazard Report Assessment of Production Scenarios in Groningen" as requested in his letter. If you need additional information, please do not hesitate to contact us. Yours sincerely, Prof. dr. L.G. Evers Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management Utrechtseweg 297 3731 GA De Bilt 1 "Adviesvragen rond veiligheidsrisico's en versterkingsopgave" Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute Ministry of lnfrastructure and Water Management Seismic Hazard Assessment of Production Scenarios in Groningenl A report prepared for the Ministry of Economical Affaires and Climate Policy Jesper Spetzler, Bernard Dost and Laslo Evers Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, Ministry of lnfrastructure and Water Management Utrechtseweg 297 3731 GA De Bilt June 15, 2018 1 "Adviesvragen rond veiligheidsrisico's en versterkingsopgave" i . Summary The effects of proposed changes to gas production from the Groningen gas field have been investigated for the period 2018-2027. -

Emergency Assistance After Turkish Airlines Aircraft Accident

Emergency assistance after Turkish Airlines aircraft accident, Haarlemmermeer 25 February 2009 Emergency assistance after Turkish Airlines aircraft accident, Haarlemmermeer 25 februari 2009 The Hague, July 2010 (project number M2009CH0225-02) The reports of the Dutch Safety Board are available to the public. All reports are also available on the website of the Dutch Safety Board: www.safetyboard.nl THE DUTCH SAFETY BOARD The Dutch Safety Board was established to investigate and determine the causes or probable causes of individual incidents or categories of incidents in all sectors. The sole purpose of a Dutch Safety Board investigation is to prevent future accidents or incidents and, if outcomes give cause to do so, issue associated recommendations. The organisation consists of a Board with five permanent mem- bers, a professional Bureau manned by investigators and support staff and a number of permanent committees. Guidance committees are set up to oversee specific investigations. Board Advisory committee Chairman: Pieter van Vollenhoven Annie Brouwer-Korf Vice chairman J.A. Hulsenbek J.P. Visser Annie Brouwer-Korf B.J.M. Ale F.J.H. Mertens Mrs G.H. Faber J.P. Visser A.H.P. van Gils J. Groeneweg N.S. Klazinga P.J.P.M. van Lochem P. Patka General Secretary: M. Visser Project leader: R. Smits Visitors address: Anna van Saksenlaan 50 Correspondence address: Postbus 95404 2593 HT Den Haag 2509 CK Den Haag Telephone: +31 (0)70 333 7000 Fax: +31 (0)70 333 7077 Internet: www.safetyboard.nl This report is published in the Dutch and English languages. In the event of conflict in interpretation, the Dutch text will be deemed binding. -

Beknopte Stand Van Zaken Netwerkanalyses Verkeer En Vervoer – Mei 2006

Beknopte stand van zaken netwerkanalyses verkeer en vervoer – mei 2006 Groningen-Assen De regie van de netwerkanalyse ligt bij het Projectbureau Regio Groningen-Assen. De Regio Groningen-Assen is een samenwerkingsverband van de provincies Drenthe en Groningen en de gemeenten Assen, Bedum, Groningen, Haren, Hoogezand- Sappemeer, Leek, Noordenveld, Slochteren, Ten Boer, Tynaarlo, Winsum en Zuidhorn. Verder nemen ook het OV-bureau Groningen Drenthe, ProRail en het ministerie van Verkeer en Waterstaat actief deel aan de netwerkanalyse. Maatschappelijke organisaties zoals de Kamers van Koophandel, VNO-NCW, EVO, TLN, NS, Arriva, VervoersCoördinatieCentrum Noord-Nederland, milieufederaties worden betrokken via workshops. De scope van de netwerkanalyse is de Regio Groningen-Assen. De nadruk ligt op de interne bereikbaarheid van de Regio, maar er wordt ook gekeken naar de onderlinge bereikbaarheid van de economische kernzones in Noord-Nederland, de rest van Nederland en Noord-Duitsland/Scandinavië. Er vindt onderlinge afstemming plaats met de overige netwerkanalyses in Noord- Nederland. De netwerkanalyse kijkt naar alle modaliteiten. De uitwerking naar oplossingen is gebaseerd op de zevensprong van Verdaas. Voor de zomer van 2005 is de netwerkanalyse van start gegaan. Volgens de planning zal de Stuurgroep van de Regio Groningen-Assen begin juli 2006 besluiten nemen over de netwerkanalyse. Dit besluit wordt uitgewerkt naar het eindresultaat dat voor 1 augustus wordt aangeboden aan de minister van Verkeer en Waterstaat. Het resultaat van de netwerkanalyse wordt in de tweede helft van 2006 vertaald naar een bijgesteld meerjareninvesteringsprogramma voor de Regio Groningen-Assen. Leeuwarden/Westergo-zone/A7 (LWA7) Provincie Fryslân is trekker. Verder zijn in de projectgroep vertegenwoordigd: de gemeenten Leeuwarden, Harlingen (namens de Westergo-zone) en Heerenveen (namens de A7-zone), het ministerie van Verkeer en Waterstaat, NS, ProRail, en de OV-onderneming die de concessie verkrijgt.