Integrated Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

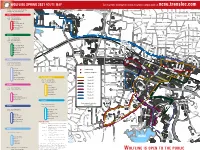

Wolfline Is Open to the Public

WOLFLINE SPRING 2021 ROUTE MAP Get real-time information on bus locations campus-wide at ncsu.transloc.com LITTLE LAKE HILL DR D R WADE R E AVE B R D G P TO A LYON ST E BLUE D D T R E N I N R ER IDGE WADE AVE B Weekday service operates Monday through Friday. LY WAD I U KAR RD E R AVE OOR LEONARD ST R AM Y P I M RAND DR 440 MAYFAIR RD M TO EXIT R Following are time points and major stops: 4 RAMP MAR A I WB D 4 BALLYHASK PL NOS 40 BLUE RIDGE RD TO WADE AVE RAMP EB B GRANT AVE RA E M P J WE STCHAS P M DUPLIN RD R E â (!BLVD A REDBUD LN WB R DR CBC Facilities Svc Ctr CT ROUTE 30 4 BROOKS AVE T WELDON PL (! I WELLS AVE TUS BAEZ ST EX T 7:00 am – 4:30 pm, 9 minute frequency 0 E 4 M MITCHELL ST HORSE LN 4 I 4:30 pm – 7:30 pm, 14 minute frequency HY â â CANTERBURY RD 7:30 pm – 12:00 am, 25 minute frequency PECORA LN RUMINANT LN ü" LN DOGWOOD VE Power Plant !! A RY LN VIEW CT CAMERON Wolf Village IN DR ER PE H Wendel Murphy Center T C OBERRY ST R R Reprod Physiology U O NCSUC Centennial RD ES King Village (Gorman St) H RY M ET TER DA L D Meredith SATULA AVE R Current Dr/Stinson Dr G Biomedical Campus FAIRCLOTH ST O BEAVER DIXIE TRL Main Vet School College BARMETTLER ST Yarbrough Dr/Stinson Dr TRINITY RD IDGE (! R E SONORA ST â T University Club Y C Student Health HLE BLU N A S MA MAYVIEW RD IEW RD DR Y AYV (! DR MOORE WILLIAM B VIEW RD M PHY W CVM Research T (! R P STACY ST U AM M S M R E Terry Medical Center 3 R R EDITH E A IT T D X C S RUFFIN ST N E D N E O L L EG ROSEDALE AVE LI 0 R 4 ST TOWER 4 A T I G ROUTE 40 S FOWLER AVE ST PARKER R â (! -

K Now Ledge Is Flow Er Pow Er

25 Years - Four Celebrations Knowledge is Flower Power! March 17-18, 2013 J.C. Raulston Arboretum/NCSU Raleigh, North Carolina North Carolina is a leader in the U.S. cut flower industry. It boasts almost 40 ASCFG members, who produce a wide range of floral products, from annuals and perennials to woodies and grasses. Cut flowers are enjoying a renaissance at farmers’ markets, through florists and events buyers, and play a large role in the movement to local products. Growing conditions vary greatly from mountains in the west to piedmont in the east, allowing growers to produce almost year-round. North Carolina State University is recognized as the only university in the United States with a comprehensive research program on greenhouse and field cut flowers. The program includes new cultivar evaluations, production studies, postharvest experiments, and marketing analysis. In cooperation with ASCFG, NCSU coordinates the National ASCFG Cut Flower Trial Programs. Tours will include cut flower growers Peregrine Farms and Wild Hare Farms, as well as the J.C. Raulston Arboretum, a nationally acclaimed garden with one of the largest and most diverse collections of landscape plants adapted for landscape use in the Southeast. Plants especially adapted to Piedmont North Carolina conditions are collected and evaluated in an effort to find superior plants for use in southern landscapes. Start your 2013 season off with inspiration and information! Sunday, March 17 Tours: Wild Hare Farm, Peregrine Farm, and the J.C. Raulston Arboretum. See reverse for schedule. Monday, March 18 8:00 a.m. Welcome to North Carolina! John Dole, NCSU, and Charles Hendrick, Yuri Hana Flower Farm, Conway, South Carolina 8:30 a.m. -

Indianapolis Museum of Art Reciprocal Museums/Institutions

Indianapolis Museum of Art Reciprocal Museums/Institutions Updated: June 20, 2017 The IMA is a member of the following Reciprocal Organizations: Reciprocal Organization of Associated Museums (ROAM), Metropolitan Reciprocal Museums (MRP), American Horticultural Society (AHS), and Museum Alliance Reciprocal Program (MARP) PLEASE NOTE: The IMA is no longer a member of the North American Reciprocal Museums. Always contact the reciprocal museum prior to your visit as some restrictions may apply. State City Museum ROAM AHS MRP MARP AK Anchorage Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center X AK Anchorage Alaska Botanical Gardens X AL Auburn Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art X AL Birmingham Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (AEIVA), UAB X AL Hoover Aldridge Gardens X AL Birmingham Birmingham Botanical Gardens X AL Dothan Dothan Area Botanical Gardens X AL Huntsville Huntsville Botanical Garden X AL Mobile Mobile Botanical Gardens X AR Fayetteville Botanical Garden of the Ozarks X AR Hot Springs Garvan Woodland Gardens X AZ Phoenix Phoenix Art Museum X AZ Flagstaff The Arboretum at Flagstaff X AZ Phoenix Desert Botanical Garden X AZ Tucson Tohono Chul X CA Bakersfield Kern County Museum X CA Berkeley UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive X CA Berkeley UC Botanical Garden at Berkeley X CA Chico The Janet Turner Print Museum X CA Chico Valene L. Smith Museum of Anthropology X CA Coronado Coronado Museum of History & Art X CA Davis Jan Shrem & Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art X CA Davis UC Davis Arboretum and Public Garden X X CA El -

ACCESS North Carolina

ACCESS North Carolina A Vacation and Travel Guide for People with Accessibility Needs ACCESS North Carolina How to Use ACCESS North Carolina ACCESS North Carolina uses a mix of text and icons to present basic tourist site accessibility information. Icons allow you to tell at a glance if a site is accessible, partially accessible or not accessible for a person with a specific type of disability. Those icons look like this: Accessible: The site provides substantial accessibility. Partially Accessible: The site provides some accessibility. Not Accessible: The site provides limited accessibility. Thumbs Up: This points out a good practice that the site does. The North Carolina State Building Code Accessibility Code, the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines, tourist site accessibility survey responses and observations from site visits were used to determine accessibility ratings. Cover Photo Descriptions Top left: Randy Holcombe uses a beach access mat in Nags Head. Top right: The Durham Bulls Athletic Park shows sign language interpreter Caterina Phillips signing the National Anthem on the outfield video screen. Bottom left: Travel blogger Cory Lee enjoys a visit to the Biltmore Estate. Bottom right: Ed Summers uses an app that allows visitors with vision loss to explore the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Center: Kevin Williams, Twila Adams and Andy Arnette prepare to play a round of wheelchair-accessible mini golf at Dan Nicholas Park. ii ACCESS North Carolina Travel Accessibility Survey Please answer the following questions to help us better understand the needs of travelers with disabilities in North Carolina. Thank you very much for your time! 1. -

Blue Ridge Road District Study Final Report

raleigh, nc | august 2012 Blue Ridge Road District Study © 2012 urban design associates Blue Ridge Road District Study Prepared by Urban Design Associates JDavis Architects Martin Alexiou Bryson RCLCO Long Leaf Historic Resources Acknowledgements CITY COUNCIL Nancy McFarlane, City of Raleigh Mayor Russ Stephenson, Mayor Pro Tem Mary Ann Baldwin, Council Member At Large Randall Stagner, Council Member, District A John Odom, Council Member, District B Eugene Weeks, Council Member, District C Thomas Crowder, Council Member, District D Bonner Gaylord, Council Member, District E CITY MANAGER J. Russell Allen DEPARTMENT OF CITY PLANNING Mitchell Silver, Chief Planning and Development Officer & Director CONSULTANT TEAM Urban Design Associates JDavis Architects Martin Alexiou Bryson RCLCO Long Leaf Historic Resources CORE STAKEHOLDER ADVISORY TEAM Blue Ridge Reality Centennial Authority Highwoods Properties North Carolina Department of Administration (NCDOA) North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) North Carolina State Fairgrounds North Carolina State University (NCSU) North Carolina Sustainable Communities Task Force Rex UNC Health Care ii blue Ridge Road District Study CITY OF RALEIGH PROJECT TEAM Grant Meacci, PLA, LEED ND, Project Director Trisha Hasch, Project Manager Land Use, Transit, & Transportation Urban Forestry Roberta Fox, AIA Sally Thigpen Eric Lamb, PE Mike Kennon, PE Parks and Greenways David Eatman Vic Lebsock Fleming El-Amin, AICP Ivan Dickey David Shouse GIS Support Lisa Potts Carter -

The Magnolia Collection at the Jc Raulston Arboretum

tvtagnotia The Magnolia collection at the jC Raulston Arboretum at NC State University Mark Wearhington, Assisrant Director and Curator of Collections, /C Raulsron Arboretum at NC State University, Raleigh, NC The JC Raulston Arboretum The JC Raulston Arboretum (JCRA) is a nationafly acclaimed garden with one of the most diverse collections of cold-hardy temperate zone plants in the southeastern United States. As a part of the Department of Horticul- tural Science at NC State University in Raleigh, NC, the JCRA is primarily a research and teaching garden that focuses on the evaluation, selection and display of plant material gathered from around the world and plant- ed in landscape settings. Plants especially adapted to Piedmont North Carolina conditions are identified in an effort to increase the diversity in southern landscapes. The JCRA's 10 acres and nursery contains over 8300 accessions of over 5000 different taxa. The JCRA's location in the central piedmont of North Carolina allows us to grow a wide diversity of plant material. Our temperatures generally range from about -12'C (10'F) to 35'C (95'F), but temperatures much low- er and higher are not unknown. The average annual precipitation mea- sures 109cm (43 in) and in most months the area receives about 7.5-10cm (3-4in). The Njagnofia collection Magnolios have been an important part of the collections of the JCRA from its inception and we are currently applying to be part of the multi- institution North American Plant Collections Consortium Magnolia collec- tion. The first accessioned magnolia dates to 1977, less than a year after the arboretum founder and namesake, J.C. -

The JC Raulston Arboretum Beyond the Garden Walls

Moonlight in the Garden at the JC Raulston Arboretum Starting from Scratch, a Beginner's Guide to Developing New Events The JC Raulston Arboretum at NC State Established in 1976 by Dr. J. C. Raulston NC State University Professor “90% of the nursery market is made up of 40 different plants.” Mission: To introduce, display, and promote plants that diversify the American landscape University Research Garden Raleigh, North Carolina 10.5 Acres 7,450 taxa in living collection Plant Collections Network: Redbud Collection Magnolia Collection Admission Free Annual Visitation est. 50,000+ $1,045,00 Budget Size & Budget 38 Percentile of Public Gardens Staff 6 Full-time 13 Part-time 10 Seasonal 306 Volunteers 2,555 Members 16.4 Full-time Equivalent 1 Adult Education & Event Coordinator 210 Adult Education Programs 2 Annual Fundraisers Another Event? WHY? ADDED REVENUE STREAM INCREASE AWARENESS NEW AUDIENCE DRIVE MEMBERSHIP NEW EXPERIENCE FOR EXISTING AUDIENCE WHAT? FUNDRAISER FALL EVENT, AFTER DARK MISSION FOCUSED PUBLIC EVENT MULTI-NIGHT, MULTI-WEEKEND UNQIUE EXPERIENCE ADULT BEVERAGE HOW? What does it look like? What type of experience? How to stay on mission, keeping the garden as the main attraction? Set Budget Revenue Goals Attendance Goals Decide Dates Budget: $15,000 Revenue Goal: Break Even Attendance Goals: 1,000 each Weekend First 2 weekends in November Scope of Event Impact on Staff Traffic Pattern Impact on Garden Guest Experience Challenges Limited Parking Advance Ticketing Limited Staff Ticket Price Safe Crowd Flow NC State Football University Alcohol Policy Rain Plan How to Light the Garden? Who do you know? Who do they know? How to move forward? Donated Lighting Plan Donated Labor to Install Help with the Asks from Distributors Donated/Loaned Needed Materials southernlightsinfo.com ESTABLISH EXPECTATIONS JC Raulston Arboretum at NC State Southern Lights of Raleigh, Inc. -

Friends of the JC Raulston Arboretum

Friends of the JC Raulston Arboretum NewsletterSpring 2015 – Vol. 18, No. 1 Director’s Letter Friends of the JC Raulston Arboretum Newsletter Spring 2015 – Vol. 18, No. 1 Christopher Todd Glenn, Editor [email protected] Photographs by Tim Alderton, Susan Bailey, Harriet Bellerjeau, Onur Dizdar, Christopher Todd Glenn, Annie Hibbs, and Mark Weathington © March 2015 JC Raulston Arboretum JC Raulston Arboretum NC State University 4415 Beryl Road Campus Box 7522 Raleigh, NC 27606-1457 Raleigh, NC 27695-7522 Phone: (919) 515-3132 Greetings from the JCRA Fax: (919) 515-5361 jcra.ncsu.edu www.facebook.com/jcraulstonarboretum/ jcraulstonarboretum.wordpress.com By Mark Weathington, It is with great pleasure that I pen my first letter as director www.youtube.com/jcraulstonarb/ www.pinterest.com/jcrarboretum/ Director of the JC Raulston Arboretum. While the plants were what Arboretum Open Daily first drew me to the JCRA, it was always the significant im- April–October – 8:00 am–8:00 pm pact of the Arboretum that really spoke to me. The JCRA has long been a driving November–March – 8:00 am–5:00 pm force for improving the Green Industry, and it has been estimated that plants Ruby C. McSwain Education Center Monday–Friday – 8:00 am–5:00 pm introduced to the industry by the JCRA have contributed $10.5 million per year to the ornamental nursery industry. As I look at the catalogs that fill my mailbox Bobby G. Wilder Visitor Center Monday–Friday – 8:00 am–5:00 pm at this time of year, I think J. C. would be pleased that his vision to “diversify the Saturday* – 10:00 am–2:00 pm Sunday* – 1:00 am–4:00 pm American landscape” has indeed become a reality. -

City of Raleigh Neighborland Perry Street Studio LLC Dorothea Dix Park Master Plan Community Outreach & Engagement Executive Summary

Public Engagement Source: City of Raleigh Neighborland Perry Street Studio LLC Dorothea Dix Park Master Plan Community Outreach & Engagement Executive Summary The City of Raleigh, with the support of the Dorothea Dix Park Conservancy, is leading a generational effort to develop Dorothea Dix Park. This success of this effort lies in the ability to create a deep and meaningful connection between the community and the park. In terms of scale and scope, the outreach associated with the Master Plan is unprecedented in city projects. This strategy presents a thoughtful, coordinated and ambitious approach to meaningful outreach and engagement. Parks are one of the most democratic spaces in a community. The City of Raleigh has made it a priority to create a diverse and equitable master planning process for Dix Park that serves all of Raleigh’s residents and beyond. The Outreach and Engagement Strategy is couched in an equity framework that details the objectives, implementation, and evaluation of an inclusive and accessible planning process. This strategy takes a multi-faceted and flexible approach to outreach and engagement. From traditional community meetings to experience-based events, programs and online participation, this strategy provides multiple channels to reach a broad and diverse audience. The goal is to provide a variety of opportunities for individuals to explore and shape the future of Dorothea Dix Park. Finally, this strategy was built around the schedule set forth by the Master Plan consultant, Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA). Engagement opportunities were be designed to facilitate dialogue between the community and MVVA. The process was iterative with engagement continually informing the evolution of the Dorothea Dix Park Master Plan. -

Volume 27, No. 2 Southeastern Conifer

S. Horn Volume 27, no. 2 Southeastern Conifer Quarterly June 2020 American Conifer Society Southeast Region Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia From the Southeast Region President What an interesting spring and early summer we are having this year. I know we all have spent many more hours in our gardens than we normally would. I am sure it has helped many of us through these trying times. We have unfortunately had to cancel most of the Conifer Society events for the year. But I do hope that members will try to have a few small get togethers to show off their gardens. There are several ways members can make this happen. The membership list is searchable on the website and you can send members in your area an email letting them know you want to have an open garden. The other way is to announce it on the ACS Southeast Facebook page (American Conifer Society Southeast Group), and see who shows up. Just remember to follow the latest CDC recommendations regarding COVID-19. If you do have an open garden or just want to share photos of your garden, please post them on the Facebook page (American Conifer Society Southeast Group, (https://www.facebook.com/groups/351809468684900/) or send them to Sandy to put into an article for next issue. Some good news is we are already planning on having our 2021 Regional Meeting in Knoxville, the first weekend in May. Dr. Alan Solomon has agreed to be on tour. His garden is aptly named GATOP (God’s Answer To Our Prayers). -

Raleigh, North Carolina

Coordinates: 35°46′N 78°38′W Raleigh, North Carolina Raleigh (/ˈrɑːli/; RAH-lee)[6] is the capital of the state of North Carolina and the seat of Wake County in the United States. Raleigh is known as the "City of Oaks" for its many Raleigh, North Carolina [7] oak trees, which line the streets in the heart of the city. The city covers a land area of State capital city 147.6 square miles (382 km2). The U.S. Census Bureau estimated the city's population as City of Raleigh 474,069 as of July 1, 2019.[4] It is one of the fastest-growing cities in the country.[8][9] The city of Raleigh is named after Walter Raleigh, who established the lost Roanoke Colony in present-day Dare County. Raleigh is home to North Carolina State University (NC State) and is part of the Research Triangle together with Durham (home of Duke University and North Carolina Central University) and Chapel Hill (home of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). The name of the Research Triangle (often shortened to the "Triangle") originated after the 1959 creation of Research Triangle Park (RTP), located in Durham and Wake counties, among the three cities and their universities. The Triangle encompasses the U.S. Census Bureau's Raleigh-Durham-Cary Combined Statistical Area (CSA), which had an estimated population of 2,037,430 in 2013.[10] The Raleigh metropolitan statistical area had an estimated population of 1,390,785 in 2019.[11] Most of Raleigh is located within Wake County, with a very small portion extending into Durham County.[12] The towns of Cary, Morrisville, Garner, Clayton, Wake Forest, Apex, Holly Springs, Fuquay-Varina, Knightdale, Wendell, Zebulon, and Rolesville are some of Raleigh's primary nearby suburbs and satellite towns. -

Centennial Campus

Visitor’s Guide NC State University Talley Student Union Talley Student Union is the hub for quality student-life experiences and community-building on campus. It features a grand ballroom, a wide variety of dining, lounging and meeting venues, recreational areas, student organization and government offices, and the NC State Bookstore. 5 NC State at a Glance 20 Main Campus Map 6 History 22 Biomedical Campus Map Educational Leadership 23 Centennial Campus Map 9 Hillsborough Traditions 24 Hillsborough Street Map 10 Undergraduate Admissions 26 Raleigh Diversity 28 Polar Plunge 13 Real-World Learning Golf and Dine at NC State Outreach and Extension 31 Athletics 14 Research and Centennial Campus 32 Park Alumni Center 17 Service Red and White for Life Hunt Library 34 Directory 18 Open House Visitor Parking Faculty & Staff 2,336 faculty NC State Student-faculty ratio 13:1 The Chancellor’s Faculty Excellence Program brings some of the best and brightest minds to join NC State at a Glance University’s interdisciplinary efforts to solve some of the globe’s most significant problems. Guided by a strong North Carolina State University is a large, strategic plan and an aggressive vision, the cluster hiring comprehensive university known for its leadership in program has added 58 new faculty members in 20 select education and research, and is globally recognized for fields to add more breadth and depth to NC State’s science, technology, engineering and mathematics. already-strong efforts. Interdisciplinary clusters include bioinformatics, personalized medicine and public science As one of the leading land-grant institutions in the 25 faculty are members of the prestigious nation, NC State is committed to playing an active and National Academies vital role in improving quality of life for the citizens of North Carolina, the nation and the world.