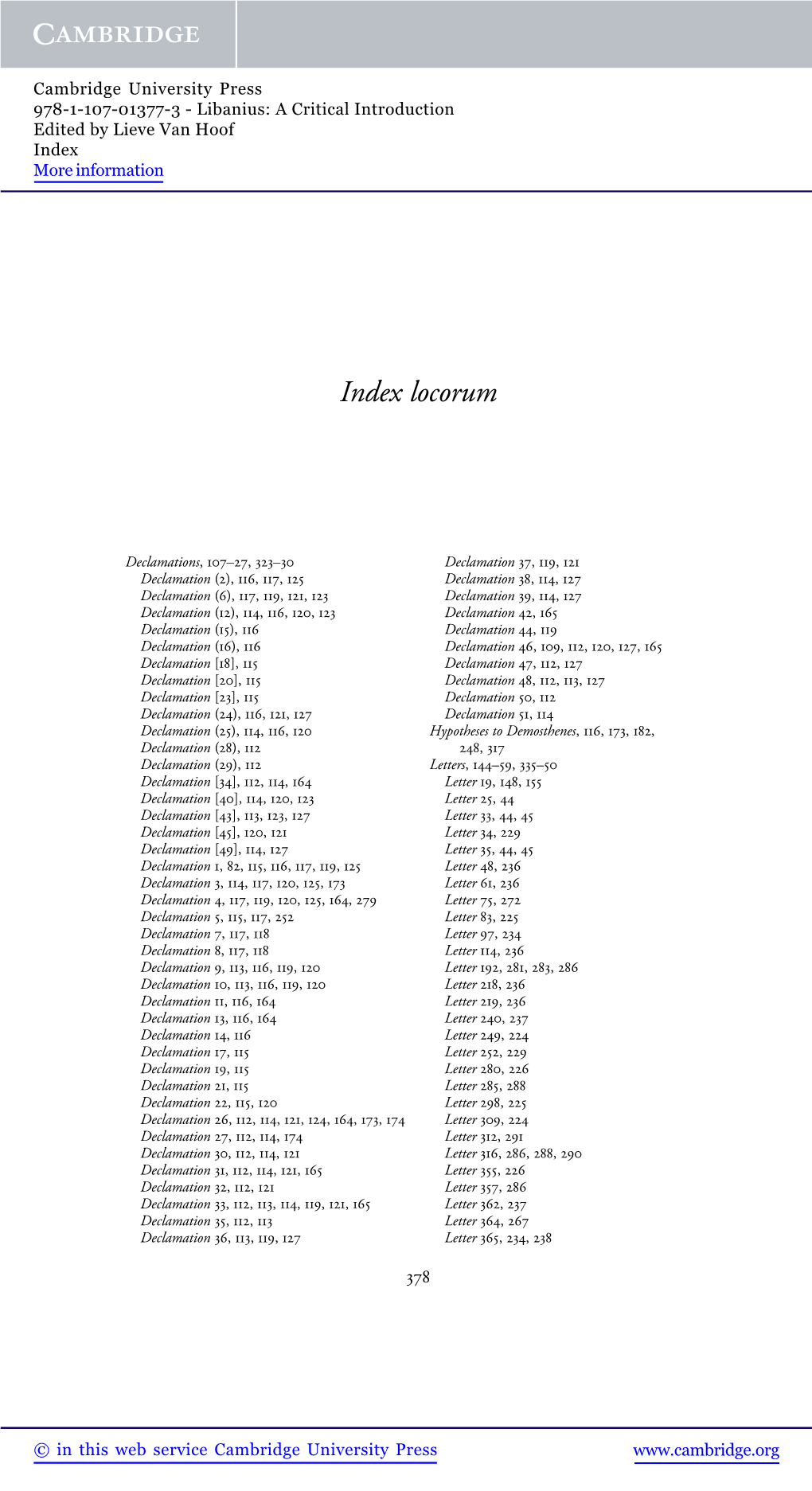

Index Locorum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXVI

Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXVI Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXVI By J. den Boeft, J.W. Drijvers, D. den Hengst and H.C. Teitler LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 This book is printed on acid-free paper. A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN: 978 90 04 16212 9 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in aretrievalsystem,ortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronic,mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands CONTENTS Preface ................................. vii Introduction ........................... ix A noteonchronology ................. xv Legenda ................................ xxvii Commentary on Chapter 1 ........... 1 Commentary on Chapter 2 ........... 37 Commentary on Chapter 3 ........... 59 Commentary on Chapter 4 ........... 75 Commentary on Chapter 5 ........... 93 Commentary on Chapter 6 ........... 125 Commentary on Chapter 7 -

INTRODUCTION in the Late Fourth Century, Athens Came Under The

INTRODUCTION In the late fourth century, Athens came under the spell of one of the more colourful and complex fi gures of her history: Demetrius of Phalerum. A dilettante who bleached his hair and rouged his cheeks, a man whose luxurious banquets were conducted in perfumed and mosaic-clad rooms, Demetrius was also a product of Aristotle’s philo- sophical establishment, the Peripatos, and a remarkably accomplished scholar in his own right. Th is erudite and urbane fi gure rose from political obscurity to rule his native city for the decade 317–307. His regime occupies a vital transitional period of Athenian history. In temporal terms, it provides the link between the classical Athens of Lycurgus and the emerging Hellenistic city of the third century. It was a time at which Athens was still held fi rmly under the suzerainty of Macedon, the dominant world power of the day, as it had been already for three decades, but the very nature of that suzerainty was being re-defi ned. For much of the previous three decades, Athens had been but one of numerous Greek states subordinated to the northern super-power by a web of treaties called the League of Corinth. By the time of Demetrius, both Philip and Alexander, the greatest of the Macedonian kings, were gone and the Macedonian world itself was fragmenting. Alexander’s subordi- nates—the so-called Diadochoi—were seeking to carve out kingdoms for themselves in Alexander’s erstwhile empire, and in the resulting confusion, individual Greek states were increasingly becoming infl u- ential agents and valued prizes in the internecine strife between war- ring Macedonian generals. -

Aelius Aristides , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 27:3 (1986:Autumn) P.279

BLOIS, LUKAS DE, The "Eis Basilea" [Greek] of Ps.-Aelius Aristides , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 27:3 (1986:Autumn) p.279 The Ei~ BauLAea of Ps.-Aelius Aristides Lukas de Blois HE AUTHENTICITY of a speech preserved under the title El~ Ba T utAia in most MSS. of Aelius Aristides (Or. 35K.) has long been questioned.1 It will be argued here that the speech is a basilikos logos written by an unknown author of the mid-third century in accordance with precepts that can be found in the extant rhetorical manuals of the later Empire. Although I accept the view that the oration was written in imitation of Xenophon's Agesilaus and Isoc rates' Evagoras, and was clearly influenced by the speeches of Dio Chrysostom on kingship and Aristides' panegyric on Rome,2 I offer support for the view that the El~ BautAia is a panegyric addressed to a specific emperor, probably Philip the Arab, and contains a political message relevant to a specific historical situation. After a traditional opening (§ § 1-4), the author gives a compar atively full account of his addressee's recent accession to the throne (5-14). He praises the emperor, who attained power unexpectedly while campaigning on the eastern frontier, for doing so without strife and bloodshed, and for leading the army out of a critical situation back to his own territory. The author mentions in passing the em peror's education (1lf) and refers to an important post he filled just before his enthronement-a post that gave him power, prepared him for rule, and gave him an opportunity to correct wrongs (5, 13). -

The Rhetoric of Corruption in Late Antiquity

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Rhetoric of Corruption in Late Antiquity A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Tim W. Watson June 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Michele R. Salzman, Chairperson Dr. Harold A. Drake Dr. Thomas N. Sizgorich Copyright by Tim W. Watson 2010 The Dissertation of Tim W. Watson is approved: ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In accordance with that filial piety so central to the epistolary persona of Q. Aurelius Symmachus, I would like to thank first and foremost my parents, Lee and Virginia Watson, without whom there would be quite literally nothing, followed closely by my grandmother, Virginia Galbraith, whose support both emotionally and financially has been invaluable. Within the academy, my greatest debt is naturally to my advisor, Michele Salzman, a doctissima patrona of infinite patience and firm guidance, to whom I came with the mind of a child and departed with the intellect of an adult. Hal Drake I owe for his kind words, his critical eye, and his welcome humor. In Tom Sizgorich I found a friend and colleague whose friendship did not diminish even after he assumed his additional role as mentor. Outside the field, I owe a special debt to Dale Kent, who ushered me through my beginning quarter of graduate school with great encouragement and first stirred my fascination with patronage. Lastly, I would like to express my gratitude to the two organizations who have funded the years of my study, the Department of History at the University of California, Riverside and the Department of Classics at the University of California, Irvine. -

On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras

The Classical Quarterly http://journals.cambridge.org/CAQ Additional services for The Classical Quarterly: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras A. E. Taylor The Classical Quarterly / Volume 11 / Issue 02 / April 1917, pp 81 - 87 DOI: 10.1017/S0009838800013094, Published online: 11 February 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009838800013094 How to cite this article: A. E. Taylor (1917). On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras. The Classical Quarterly, 11, pp 81-87 doi:10.1017/S0009838800013094 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAQ, IP address: 128.122.253.212 on 28 Apr 2015 ON THE DATE OF THE TRIAL OF ANAXAGORAS. IT is a point of some interest to the historian of the social and intellectual development of Athens to determine, if possible, the exact dates between which the philosopher Anaxagoras made that city his home. As everyone knows, the tradition of the third and later centuries was not uniform. The dates from which the Alexandrian chronologists had to arrive at their results may be conveniently summed up under three headings, (a) date of Anaxagoras' arrival at Athens, (6) date of his prosecution and escape to Lampsacus, (c) length of his residence at Athens, (a) The received account (Diogenes Laertius ii. 7),1 was that Anaxagoras was twenty years old at the date of the invasion of Xerxes and lived to be seventy-two. This was apparently why Apollodorus (ib.) placed his birth in Olympiad 70 and his death in Ol. -

Pilgrimage in Graeco-Roman & Early Christian Antiquity : Seeing the Gods

9 Pilgrimage as Elite Habitus: Educated Pilgrims in Sacred Landscape During the Second Sophistic Marco Galli A Rita Zanotto Galli, con profonda amicizia e stima PATTERNS OF RELIGIOUS MEMORY AND PAIDEIA DURING THE SECOND SOPHISTIC Is it possible to reconstruct, at least in part, the suggestive and intricate frame that connected the monuments and images, the ritual actions, and the pilgrim who actively and subjectively participated as collector and observer of sacred experience? What indices permit us to trace the emotional reactions of pilgrims in contact with the sacred landscape? What mental processes and emotional reactions made the tangible objects (the monuments, the images, and the rites) into mental objects, and how did these become Wxed in the memory of the pilgrim? With these questions as guidelines, I shall argue that we can apply a contem- porary approach to the investigation of the social functions of ancient pilgrimage. For the exploration of the relationship between the religious experiences of the pilgrim and social instances of collective memory for the reconstruction and reactivation of a sacred traditional landscape, we may turn to a moment in history that provides an unusually dense 254 Marco Galli representation of the internal states of sacred experience.1 This is the period dubbed ‘The Second Sophistic’. It was a period virtually obsessed with the problem of memory, when even religious tradition, because it formed one of the most signiWcant communicative functions of collect- ive life, was subjected to fundamental revision within the process of social memory.2 Plutarch’s writings cast light on the role of memory and its interaction with religious tradition. -

Aelius Aristides As Orator-Confessor: Embodied Ethos in Second Century Healing Cults

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2019 Aelius Aristides as Orator-Confessor: Embodied Ethos in Second Century Healing Cults Josie Rose Portz University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Portz, Josie Rose, "Aelius Aristides as Orator-Confessor: Embodied Ethos in Second Century Healing Cults. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Josie Rose Portz entitled "Aelius Aristides as Orator-Confessor: Embodied Ethos in Second Century Healing Cults." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Janet Atwill, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Jeffrey Ringer, Tanita Saenkhum Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) AELIUS ARISTIDES AS ORATOR-CONFESSOR: EMBODIED ETHOS IN SECOND CENTURY HEALING CULTS A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Josie Rose Portz August 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my wonderful committee who has supported me these past two years in furthering my education in rhetorical studies, many thanks. -

Graeca Tergestina Storia E Civiltà 5 Graeca Tergestina Storia E Civiltà

GRAECA TERGESTINA STORIA E CIVILTÀ 5 GRAECA TERGESTINA STORIA E CIVILTÀ Studi di Storia greca coordinati da Michele Faraguna Opera sottoposta a peer review secondo il protocollo UPI – University Press Italiane impaginazione Gabriella Clabot © copyright Edizioni Università di Trieste, Trieste 2018. Questo volume è integralmente disponibile online a libero accesso nell’archivio digitale OpenstarTs, al link: Proprietà letteraria riservata. https://www.openstarts.units.it/handle/10077/8648 I diritti di traduzione, memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento totale e parziale di questa pubblicazione, con qualsiasi mezzo (compresi i microfilm, le fotocopie e altro) sono riservati per tutti i paesi. ISBN 978-88-8303-922-5 (print) ISBN 978-88-8303-923-2 (online) EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste via Weiss 21, 34128 Trieste http://eut.units.it https://www.facebook.com/EUTEdizioniUniversitaTrieste Eubulo e i Poroi di Senofonte LʼAtene del IV secolo tra riflessione teorica e pratica politica Livia De Martinis EUT EDIZIONI UNIVERSITÀ DI TRIESTE A mia madre Indice Abbreviazioni IX Premessa XIII Introduzione 1 Capitolo I – Eubulo: ricostruzione biografica (400/399 a.C. ca. – ante 330 a.C.) 5 1. L’uomo 7 1.1. I dati anagrafici 7 1.2. La carica arcontale 9 2. Gli inizi dell’attività politica 10 2.1. Il decreto per il ritorno di Senofonte e l’appartenenza alla cerchia di Callistrato 10 2.2. Gli esordi in politica internazionale 13 2.3. L’attivismo diplomatico e la rinuncia a una politica militare attiva 15 2.4. La pace di Filocrate 20 3. L’apice dell’attività economico-amministrativa 21 3.1. -

The Regime of Demetrius of Phalerum in Athens, 317–307

Th e Regime of Demetrius of Phalerum in Athens, 317–307 BCE Mnemosyne Supplements History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity Edited by Susan E. Alcock, Brown University Th omas Harrison, Liverpool Willem M. Jongman, Groningen H.S. Versnel, Leiden VOLUME 318 Th e Regime of Demetrius of Phalerum in Athens, 317–307 BCE A Philosopher in Politics By Lara O’Sullivan LEIDEN • BOSTON 2009 On the cover: Detail of the Parthenon. Photo: Author. Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data O’Sullivan, Lara. Th e rule of Demetrius of Phalerum in Athens, 317-307 B.C. : a philosopher in politics / by Lara O’Sullivan. p. cm. — (Mnemosyne supplements. History and archaeology of classical antiquity, ISSN 0169-8958 ; v. 318) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-17888-5 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Demetrius, of Phaleron, b. ca. 350 B.C. 2. Demetrius, of Phaleron, b. ca. 350 B.C.—Political and social views. 3. Governors—Greece—Athens—Biography. 4. Statesmen—Greece—Athens— Biography. 5. Orators—Greece—Athens—Biography. 6. Philosophers, Ancient— Biography. 7. Athens (Greece)—Politics and government. 8. Philosophy, Ancient. 9. Athens (Greece)—Relations—Macedonia. 10. Macedonia—Relations—Greece— Athens. I. Title. II. Series. DF235.48.D455O87 2009 938’.508092—dc22 [B] 2009033560 ISSN 0169-8958 ISBN 978 90 04 17888 5 Copyright 2009 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Th e Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Anaxagoras Janko Revised 2020

The Eclipse that brought the Plague: Themistocles, Pericles, Anaxagoras, and the Athenians’ War on Science• Abstract: The biography of Anaxagoras (500–428 BCE), the most brilliant scientist of antiquity, contains many unresolved contradictions, which are best explained as follows. After he ‘predicted’ the fall of the meteorite at Aegospotami in 466, he lived nearby at Lampsacus as the protégé of its ruler Themistocles. In 460 Pericles became his patron at Athens, where he lived for the next thirty years. In 431, Pericles was taking part in an expedition to the Peloponnese when the sun was eclipsed; he tried to dispel his helmsman’s fear by covering his face with his cloak, illustrating Anaxagoras’ correct account of eclipses. In 430 he led a second such expedition, which failed badly; its return coincided with the plague. The seer Diopeithes brought in a decree that targeted the ‘atheist’ Anaxagoras by banning astronomy. This enabled Thucydides son of Melesias and Cleon to attack Pericles by prosecuting Anaxagoras, on the ground that Pericles’ impiety had angered the gods, thereby causing the plague. Pericles sent Anaxagoras back to Lampsacus, where he soon died; he was himself deposed and fined, in a first triumph for the Athenian populist reaction against the fifth-century Enlightenment. The most striking evidence of the reaction against the Enlightenment is to be seen in the successful prosecutions of intellectuals on religious grounds which took place in Athens in the last third of the fifth century. About 432 B.C. or a year or two later, disbelief in the supernatural and the teaching of astronomy were made indictable offences. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Proceedings Series LIT2017-0021

ATINER CONFERENCE PRESENTATION SERIES No: LIT2017-0021 ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series LIT2017-0021 Athens, 22 August 2017 Themistocles' Hetairai in a Fragment of Idomeneus of Lampsacus: A Small Commentary Marina Pelluci Duarte Mortoza Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10683 Athens, Greece ATINER’s conference paper proceedings series are circulated to promote dialogue among academic scholars. All papers of this series have been blind reviewed and accepted for presentation at one of ATINER’s annual conferences according to its acceptance policies (http://www.atiner.gr/acceptance). © All rights reserved by authors. 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PRESENTATION SERIES No: LIT2017-0021 ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series LIT2017-0021 Athens, 24 August 2017 ISSN: 2529-167X Marina Pelluci Duarte Mortoza, Independent Researcher, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil Themistocles' Hetairai in a Fragment of Idomeneus of Lampsacus: A Small Commentary1 ABSTRACT This paper aims to be a small commentary on a fragment cited by Athenaeus of Naucratis (2nd-3rd AD) in his Deipnosophistai. This is his only surviving work, which was composed in 15 books, and verses on many different subjects. It is an enormous amount of information of all kinds, mostly linked to dining, but also on music, dance, games, and all sorts of activities. On Book 13, Athenaeus puts the guests of the banquet talking about erotic matters, and one of them cites this fragment in which Idomeneus of Lampsacus (ca. 325-270 BCE) talks about the entrance of the great Themistocles in the Agora of Athens: in a car full of hetairai. Not much is known about Idomeneus, only that he wrote books on historical and philosophical matters, and that nothing he wrote survived. -

The Hadrianic Chancellery

CHAPTER 5 Governing by Dispatching Letters: The Hadrianic Chancellery Juan Manuel Cortés-Copete In the year 142 AD, Aelius Aristides was a young sophist fulfilling his dream of making an appearance in Rome to declaim before senators and, even, the emperor himself. He wished this trip would be the start of a triumphal politi- cal activity under the auspices of one of his teachers, Herodes Atticus, friend of emperors and appointed consul at Rome within that year. Illness and mys- ticism thwarted his political vocation, but never hindering the opportunity to present in public his speech Regarding Rome.1 The encomium to the city that dominated the world was composed of two series of comparisons: the superiority of Roman domination against Greek hegemonies, brief in time and space; and the kindliness of the Empire in contrast with the kingdoms that had previously tried to subdue the world.2 After indicating the flaws of the Persian Empire, the limitations of the reign of Alexander, and the failures of Hellenistic kingdoms, the sophist praised the Roman Empire. The authentic control over the ecumene by Rome and the perfection of its political structure were its arguments. This section concluded as follows (26.33): Therefore there is no need for him [the Emperor] to wear himself out by journeying over the whole empire, nor by visiting different people at different times to confirm individual matters, whenever he enters their land. But it is very easy for him to govern the whole inhabited world by dispatching letters without moving from the spot. And the letters * This article is part of the Project “Adriano y la integración de la diversidad regional” (HAR2015- 65451-C2-1-P MINECO/FEDER), financed by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Government of Spain.