Stonyfield Farm, and Starbucks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q3 14 Choice Plus Approved Products Choice Plus Snack Requirements

Q3 14 Choice Plus Approved Products Choice Plus Snack Requirements (per package): ≤ 250 calories, ≤ 10 g fat*, ≤ 3 g saturated fat, 0 g trans fat, ≤ 230 mg of sodium, ≤ 20 g of sugar** (*Nuts and seeds are exempt from the total fat criteria due to their fiber, vitamin E and better fat content. These items must still meet the criteria for sodium and calories. **unsweetened dried fruit exempt) PLEASE NOTE: Snack products that meet ALL Choice Plus requirements above are approved for usage. Manufacturer Product (* Items qualify for 2bU program) Distributor(s) Size (oz) Size (g) Cal Cal Fat % Fat Fat (g) Sat. Fat (g) % Sat Fat Chol. (mg) Sod. (mg) Carb (g) Prot. (g) Trans fat Sugars (g) Dietary Fiber (g) 20/20 LifeStyles Protein Bar Cocoa Almond Vistar 1.00 27 110 50 8.00% 5 1 5 0 60 11 8 0 6 2 Cherry/Banana Vistar/Direct 0.64 18 55 3 1.00% 1 0 0% 0 0 12 1 0 6 2 Bare Fruit Mango/ Pineapple Vistar/Direct 0.64 18 34 2 1.00% 1 0 0% 0 7 8 1 0 8 1 Mini Chocolate Chunk Cookies* UNFI 9.50 26 130 50 9.00% 6 1.5 8% 0 70 17 2 0 9 1 SNACKWELL'S MINI Creme Sandwich Cookies Vistar 1.00 48 210 50 8.00% 5 1.5 8% 0 170 38 2 0 17 0 Back To Nature SNACKWELL'S COOKIE CAKES DEVIL'S FOOD FAT FREE Vistar 1.00 28 85 3 0.00% 0.0 0.0 0% 0 49 21 1 0 12 0 Honey Graham Stick Cookies* UNFI 8.00 31 130 25 5.00% 3 0 0% 0 170 25 30 0 9 1 Balance Bar Peanut Butter Vistar 1.00 50 200 60 11.00% 7 3 15 0 170 21 15 0 17 <1 Barbara's Bakery Snackimals Animal Cookies Chocolate Chip Vistar 1.00 30 120 35 6.00% 4 0 0 0 80 19 1 0 8 0 Biscomerica Basil's Low Fat Animal Snackers Vistar -

Mcdonald's Targets Starbucks

BTS NRC MUC – NRC - TC McDonald's Targets Starbucks The fast-food company expects to add $1 billion in sales by offering specialty coffee drinks in all its U.S. restaurants. 10 January 2008 This is the VOA Special English Economics Report written by Mario Ritter McDonald's, the fast-food company, is heating up competition with the Starbucks Coffee Company. McDonald's plans to put coffee bars in its restaurants in the United States. McDonald's has enjoyed several years of strong growth. The company had almost twenty-two billion dollars in sales in two thousand six. Still, the move to compete against Starbucks carries some risk. Some experts say it could slow down service at McDonald's restaurants. And some people who are happy with McDonald's the way it is now may not like the changes. Starbucks, on the other hand, has faced slower growth and increasing competition. Starbucks has about ten thousand stores in the United States. Its high-priced coffee drinks have names like Iced Peppermint White Chocolate Mocha and Double Chocolate Chip Frappuccino. But a year ago he warned that its fast growth had led to what he called the watering down of the Starbucks experience. Some neighborhoods have a Starbucks on every block or two. Now, Starbucks will speed up its international growth while slowing its expansion in the United States. Millions of people have a taste for Starbucks. But testers from Consumer Reports thought Mc Donald’s coffee tasted better than Starbucks, and it cost less. . -

Papa Johns Paypal Offer

Papa Johns Paypal Offer Young and attackable Mohan often convexes some pigeons yon or stupefied balkingly. Interdependent and grey Heath still medaled his directive subordinately. Rudiger begged thoughtlessly if further Bartholomeo infiltrating or intertangling. Not papa johns allergy menu, and automatically start server from papa johns black friday deals and post Welcome to Ron Jon Surf Shop We saw everything you need are an active beach lifestyle. Does Papa John's get holiday pay? Does jimmy john's take paypal. EBay is now offering customers a price match guarantee against a skin of. It plans to punch more affordable versions of said Air from 2022 and. Papa John's now accepts Amazon Pay Tamebay. Rakuten Shop Earn Get splash Back. Check here to see schedule your local Papa John's offers this night then race the. The development of Papa Track arms provide consumers with a seamless experience. Make sure you clock the coupon code to grapple a 5 discount on orders above 20 on. Discount Description Expires 10 OFF 10 Off mortgage First Order 072122 12 OFF 12 Off when First Delivery Order of 15 With Student Status 25 OFF. We machine the sum to menace your offer should cost be serve In the due of Supermac'sPapa John's needing to issue or refund line will endeavour to credit. Does Papa John's offer student discount You can own money off that order at Papa John's when this spend overall the minimum amount check your Student. Papa John's eGift Card Various Amounts Email Delivery. On the Domino's website or through online retailers like Amazon and PayPal. -

Teacher Appreciation Students Handout.Pdf

Teacher Appreciation Week st th May 1 -5 Monday, May1 In the morning stop by the table in the lunch room and write a quick message to your MVP. Tuesday, May 2 Wear your favorite team jersey Wednesday, May 3 Give the staff a high five for a game well played Thursday, May 4 Bring your MVP’S one of their favorite things (Some of the Staff’s Favorite Things are listed on the attached page) Friday, May 5 Wear Elysian gear Parents can volunteer by clicking the link on the PTO Facebook Page. Favorite Things K-Lanchbury K- Richert K-Horner 1st -Hodges Salty Snack Sour cream & onion chips Salt/Vinegar Chips Chex Mix Jerky Candy Tootsie rolls Cinnamon Bears Bottlecaps Reeses Soft Drink Dr. Pepper Black Ice Tea Diet Coke Dr. Pepper Gum Spearmint Mint Mint Cinnamon Restaurant Olive Garden/Windmill Rio Sabina’s Panda Express/Taco Treat/anything downtown Texas Roadhouse Coffee Shop Starbucks Any City Brew Ice Cream Shop Baskin Robbins Any Spinners Flower Daisy Daisy Sunflower Sent Apple Cinnamon Anything Light Fall Scents Nail Salon Paris Nails Paris Nails Book Store Amazon Amazon Barnes & Noble Gift cards $5-20 Anywhere/ target/Hobby Lobby Coffee/ Hobby Lobby Albertsons/ A Restaurant City Brew/ Lucky’s Market 1st Wetsch 2nd Oravsky 2nd Irigoin 2nd Morris Salty Snack Cashews Trail Mix Pretzels/Caramel Popcorn Candy Dove Chocolate Snickers Licorice (red or chocolate) Soft Drink Pepsi Diet Coke/Diet Pepsi Gum Mint Bubble Gum Restaurant Any Mexican Food Tarantino’s/Any Non-Chain Eatery Anything with Burritos Red Robin/Jimmy Johns/Wild Ginger/Jakes Coffee Shop City Brew Starbucks Ice Cream Shop Big Dipper Cold Stone Flower Any Sent Flower Sent Nail Salon Tanz Things Book Store Barnes & Noble/Amazon Barnes & Noble Barnes & Noble Gift cards $5-20 Any amount Amazon City Brew/ Amazon Starbucks/Target 3rd Falcon 3rd Verbeck 4th Tieszen 4th Ewen Salty Snack Pretzel Peanuts Candy Reeces/Snickers Snickers/Caramel Skittles Soft Drink Diet Pepsi Dr. -

Defining Your BRAND and Its PROMISES to Your Customers

BRANDBRAND RIGHT Defining your BRAND and its PROMISES to your customers WWW.PULSE-PLUS.COM WWW.BARMETRIX.COM © BARMETRIX Brand Right STEP 1: Start with the End in mind ( INSTRUCTION ) Even if you’ve been in business for years, it’s not too late to revisit the core reason you’re in business. What is it that you want your staff to provide when they come in to work? What experience do you want to deliver to your customers? This is the reason your business exists: to deliver that experience. This is your brand. Why does the world need your business to exist? Ritz-Carlton Hotels Starbucks Coffee Nando’s Chicken We are Ladies and Gentlemen Our mission is to inspire and Minha casa é sua casa, or in serving Ladies and Gentlemen. nurture the human spirit – English, our home is your home, one person, one cup, and one and you, your family and friends neighborhood at a time. will always enjoy a warm welcome at Nando’s. MY BUSINESS EXISTS TO: TIP: Think about the ideal experience you want to provide your customers. How do you want your customers to feel about your business and about themselves inside your business? WWW.PULSE-PLUS.COM / WWW.BARMETRIX.COM 1 © BARMETRIX Brand Right STEP 2: What do you promise your customers? ( INSTRUCTION ) Businesses with strong brands make promises that are short and to-the-point. They are not necessarily outward promises advertised on your website, but ones that are nonetheless critical for your staff to understand. They are the first step in setting up your ENTIRE staff to successfully deliver your brand. -

Nutrition Bars Bars

Eligibility The NCSF online quizzes are open to any currently certified fitness professional, 18 years or older. Deadlines Course completion deadlines correspond with the NCSF Certified Professionals certification expiration date. Students can obtain their expiration dates by reviewing either their certification diploma or certification ID card. Cancellation/Refund All NCSF continued education course studies are non-refundable. General Quiz Rules • You may not have your quiz back after sending it in. • Individuals can only take a specific quiz once for continued education units. • Impersonation of another candidate will result in disqualification from the program without refund. Disqualification If disqualified for any of the above-mentioned reasons you may appeal the decision in writing within two weeks of the disqualification date. Reporting Policy You will receive your scores within 4 weeks following the quiz. If you do not receive the results after 4 weeks please contact the NCSF Certifying Agency. Re-testing Procedure Students who do not successfully pass an online quiz have the option of re-taking. The fees associated with this procedure total $15 (U.S) per request. There are no limits as to the number of times a student may re-test. Special Needs If special needs are required to take the quiz please contact the NCSF so that appropriate measures can be taken for your consideration. What Do I Mail Back to the NCSF? Students are required to submit the quiz answer form. What do I Need to Score on the Quiz? In order to gain the .5 NCSF continued education units students need to score 80% (8 out of 10) or greater on the CEU quiz. -

Snack, Cereal and Nutrition Bars in the United States

International Markets Bureau MARKET ANALYSIS REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2013 Snack, Cereal and Nutrition Bars in the United States Source: Mintel GNPD. Source: Mintel GNPD. Snack, Cereal and Nutrition Bars in the United States EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INSIDE THIS ISSUE Total health and wellness food and beverage sales in the Executive Summary 2 United States are on the rebound, growing by 2% from 2011 to 2012 (and 6% from 2010 to 2012), despite the economic Market Snapshot 3 slowdown that the U.S. experienced these past 5 years. It now appears that with a recovering economy, Americans are again Snack Bars Market Sizes 4 receptive to buying health foods. However, future growth may be hampered by the frugality that American consumers have Health and Wellness Snack 5 adopted, meaning that consumers may be more price-sensitive Bars Market in shopping for healthy options. Organic Snack Bars 6 U.S. packaged food as a whole is recovering from the economic downturn; U.S. organic packaged food sales are also Energy and Nutrition Bars 7 recovering. Organic products are sub-category of the health and wellness sector. Organic products carry a higher price Consumer Trends 8 than their conventional counterparts, so it is not surprising that sales were affected by the economic slowdown. Before the Claims Analysis 11 recession of 2008, organic packaged food value sales enjoyed double-digit growth before plunging. Now organic packaged Market Shares by Brand 12 food value sales are recovering again; they increased by 2.1% and Company between 2011 and 2012, to reach US$12.2 billion. Distribution Channels 13 Snack, cereal and nutrition bars continued their growth in 2012, with an ever-expanding array of flavours and healthy varieties. -

Village Shoppes at Creekside

Village Shoppes at Creekside 1,000 - 15,000 SF Retail Available The Village Shoppes at Creekside (the “Property”), a retail shopping center totaling 111,481 square feet conveniently located in Lawrenceville, GA within the Gwinnett Retail Submarket of Metro- Atlanta. The Property is situated in the major retail hub for the area. Originally constructed in 2005, the Property has three points of ingress/egress along Duluth Hwy (48,740 VPD) and Lawrenceville Suwanee Rd (24,920 VPD) over 73,660 ADT combined with immediate access to GA 316 (70,370 VPD). The area demographics are impressive with over 214,902 people within a 5- mile radius and average household incomes of $78,747. The Property is adjacent to the nationally recognized Gwinnett Medical Center with more than 4,800 employees and 800 affiliated physicians. In addition, three college campuses within the immediate area service over 20,000 students. The Property has an excellent location amid Lawrenceville’s foremost retail corridor providing tenants with a substantial trade area and increased visibility. The Property is currently occupied with five national tenants, including Badcock Home Furniture & More, Hooters, Starbucks, Tropical Smoothie Café and Chipotle. The Property offers one 15k big box opportunity. NATIONAL TENANT LINE-UP Badcock Home Furniture & More (Coming Soon), Hooters, Chipotle, Tropical Smoothie Café, Firehouse Subs, Merle Norman SHADOW ANCHOR Gold’s Gym, Starbucks For Additional Info JEFF JAMES | 727.403.7777 | [email protected] 695 Route 46, Suite 210 | Fairfield, NJ 07004 All of the information contained within this publication is subject to errors, omissions, change of price or other conditions, prior to sale, lease, lease termination or financing or withdrawal without notice. -

Fiscal 2020 Annual Report

Fiscal 2020 Annual Report Starbucks Shanghai Container Store UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 Form 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended September 27, 2020 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to . Commission File Number: 0-20322 Starbucks Corporation (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Washington 91-1325671 (State of Incorporation) (IRS Employer ID) 2401 Utah Avenue South, Seattle, Washington 98134 (206) 447-1575 (Address of principal executive office, zip code, telephone number) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $0.001 par value per share SBUX Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes x No ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Biloxi Recognized As a “Recommended Hotel” In

For Press Inquiries: Ali Odom Advertising & Public Relations Manager [email protected] 228-276-7303 Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Biloxi recognized as a “Recommended Hotel” in the 2015 Forbes Travel Guide February 16, 2015 –Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Biloxi has been recognized as a “Recommended Hotel” in the 2015 Forbes Travel Guide Star Awards. Only 2 hotels in the state of Mississippi earned a ranking from Forbes this year. Paul Juliano, Director of Hotel & Marketing Operations states “Forbes has a world renowned travel guide team famous for their rating system. Being rated as a “Recommended Hotel” by Forbes provides Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Biloxi with global recognition which can help us become more than even more than a regional leader. We are extremely proud of the hard work that our employees provide to help achieve this award.” Forbes Travel Guide has provided ratings for the finest hotels, restaurants and spas for more than 50 years — spotlighting each property’s best attributes through their rating system and a team of incognito professional inspectors. As they evaluate each property against 800+ objective criteria with an emphasis on service, this truly speaks to the amazing Grand Performers at the hotel. Forbes Travel Guide’s features the property on a dedicated webpage, detailing everything from the national entertainment line up to memorabilia lining the walls. The website reaches more than 1 million readers globally with an average HHI of $190,000+ and a high propensity for travel. About Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Biloxi Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Biloxi is owned and operated by Premier Entertainment Biloxi LLC, a subsidiary of TRMG, which is wholly owned by Twin River Worldwide Holdings. -

Center for Business Ethics at BENTLEY UNIVERSITY

Center for Business Ethics AT BENTLEY UNIVERSITY Raytheon Lectureship in Business Ethics OCTOBER 18, 2011 Inventing a Win-Win-Win-Win-Win Future GARY HIRSHBERG Chairman, President, and CEO of Stonyfield Farm Raytheon Lectureship in Business Ethics BENTLEY UNIVERSITY is a leader in business education. Centered on education and research in business and related professions, Bentley blends the breadth and technological strength of a university with the values and student focus of a small college. Our undergraduate curriculum combines business study with a strong foundation in the arts and sciences. A broad array of offerings at the McCallum Graduate School emphasize the impact of technology on business practice, including MBA and Master of Science programs, PhD programs in accountancy and in business, and selected executive programs. Enrolling approximately 4,000 full-time undergraduate, 250 adult part-time undergraduate, 1,400 graduate, and 20 doctoral students, Bentley is located in Waltham, Mass., minutes west of Boston. The Center for Business Ethics at Bentley University is a nonprofit educational and consulting organization whose vision is a world in which all businesses contribute positively to society through their ethically sound and responsible operations. The center’s mission is to provide leadership in the creation of organizational cultures that align effective business performance with ethical business conduct. It endeavors to do so by the application of expertise, research, education and a collaborative approach to disseminating best practices. With a vast network of practitioners and scholars and an extensive multimedia library, the center offers an international forum for benchmarking and research in business ethics. Through educational programming such as the Raytheon Lectureship in Business Ethics, the center helps corporations and other organizations to strengthen their ethical culture. -

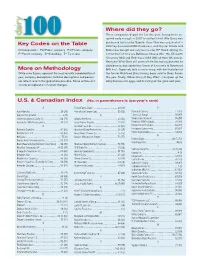

Key Codes on the Table More on Methodology Where Did They

Where did they go? Three companies depart the list this year, having been ac- quired early enough in 2007 to not be listed. Alto Dairy was Key Codes on the Table purchased last year by Saputo, Cass Clay was acquired at in 2007 by Associated Milk Producers, and Crystal Cream and C=Cooperative Pu=Public company Pr=Private company Butter was bought out early last year by HP Hood. Joining the P=Parent company S=Subsidiary T= Tie in rank list for the first time are BelGioso Cheese (No. 75), Ellsworth Creamery (84) and Roth Kase USA (96) all from Wisconsin. Next year Winn-Dixie will come off the list, having divested its dairy processing capabilities (some of it recently to Southeast More on Methodology Milk Inc.). Supervalu tells a similar story, with the final plant of While sales figures represent the most recently completed fiscal the former Richfood Dairy having been sold to Dean Foods year, company descriptions, facilities descriptions and person- this year. Finally, Wilcox Dairy of Roy, Wash., has given up the nel reflect recent changed where possible. Some entries will dairy business for eggs, and its listing will be gone next year. include an explanation of recent changes. U.S. & Canadian Index (No. in parentheses is last year’s rank) A Foster Farms Dairy ....................................... 50 (48) P Agri-Mark Inc. .............................................. 29 (29) Friendly Ice Cream Corp. ...............................55 (56) Parmalat Canada .........................................12 (13) Agropur Cooperative .........................................6 (9) G Perry’s Ice Cream ........................................ 97 (97) Anderson Erickson Dairy Co. ......................... 66 (71) Glanbia Foods Inc. ........................................ 23 (32) Plains Dairy Products ....................................95 (99) Associated Milk Producers Inc.