Occupational Folklore at the Racetrack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Codes of Ethics in Freedom Narratives Syllabus

CE 350: Codes of Ethics in Freedom Narratives Union Theological Seminary-NYC Spring Semester 2010 Tuesday 10 to 11:50 a.m. Katie G. Cannon, Ph.D. Office Hour: by appointment Course Description: This course is an interdisciplinary inquiry into the moral issues related to enslaved Africans who worked in the economies of the North America. Most scholars who study the transatlantic slave trade talk consistently about quantitative numbers and business transactions without any mention of the ethical complexities that offer a critique of the various ways that religion both empowered and disenfranchised individuals in the struggle to actualize an embodied sacred self. Close textual reading of slave novels will spell out how four centuries of chattel slavery affected Christians in previous generations and currently. Objectives: a) to examine theological themes and contemporary ethical issues in the freedom narratives of enslaved African Americans; b) to understand how novels functions as continuing symbolic expression and transformer of Christian discipleship; and c) to develop familiarity with literature in the field of study. Requirements and Procedures: - Regular class attendance and reading that is complete, careful and on schedule are essential for this course. - To help promote lively, meaningful exchange, everyone is required to complete the five steps in writing the Epistolary Journal Entry beginning with Tuesday, February 16, 2010, and each class session thereafter. - As facilitators, 1) each student will open with a devotional moment, 2) watch a clip from a slave documentary that jump-starts a conscientization free write, 3) circulate photocopies of their Epistolary Journal Entry, and 4) discuss findings with the class. -

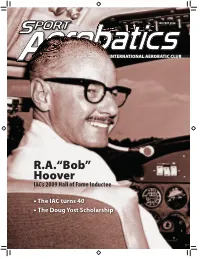

“Bob” Hoover IAC’S 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee

JANUARY 2010 OFFICIALOFFICIAL MAGAZINEMAGAZINE OFOF TTHEHE INTERNATIONALI AEROBATIC CLUB R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee • The IAC turns 40 • The Doug Yost Scholarship PLATINUM SPONSORS Northwest Insurance Group/Berkley Aviation Sherman Chamber of Commerce GOLD SPONSORS Aviat Aircraft Inc. The IAC wishes to thank Denison Chamber of Commerce MT Propeller GmbH the individual and MX Aircraft corporate sponsors Southeast Aero Services/Extra Aircraft of the SILVER SPONSORS David and Martha Martin 2009 National Aerobatic Jim Kimball Enterprises Norm DeWitt Championships. Rhodes Real Estate Vaughn Electric BRONZE SPONSORS ASL Camguard Bill Marcellus Digital Solutions IAC Chapter 3 IAC Chapter 19 IAC Chapter 52 Lake Texoma Jet Center Lee Olmstead Andy Olmstead Joe Rushing Mike Plyler Texoma Living! Magazine Laurie Zaleski JANUARY 2010 • VOLUME 39 • NUMBER 1 • IAC SPORT AEROBATICS CONTENTS FEATURES 6 R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee – Reggie Paulk 14 Training Notes Doug Yost Scholarship – Lise Lemeland 18 40 Years Ago . The IAC comes to life – Phil Norton COLUMNS 6 3 President’s Page – Doug Bartlett 28 Just for Starters – Greg Koontz 32 Safety Corner – Stan Burks DEPARTMENTS 14 2 Letter from the Editor 4 Newsbriefs 30 IAC Merchandise 31 Fly Mart & Classifieds THE COVER IAC Hall of Famer R. A. “Bob” Hoover at the controls of his Shrike Commander. 18 – Photo: EAA Photo Archives LETTER from the EDITOR OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Publisher: Doug Bartlett by Reggie Paulk IAC Manager: Trish Deimer Editor: Reggie Paulk Senior Art Director: Phil Norton Interim Dir. of Publications: Mary Jones Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh Contributing Authors: Doug Bartlett Lise Lemeland Stan Burks Phil Norton Greg Koontz Reggie Paulk IAC Correspondence International Aerobatic Club, P.O. -

MILITANT ABOLITIONIST GERRIT SMITH }Udtn-1 M

MILITANT ABOLITIONIST GERRIT SMITH }UDtn-1 M. GORDON·OMELKA Great wealth never precluded men from committing themselves to redressing what they considered moral wrongs within American society. Great wealth allowed men the time and money to devote themselves absolutely to their passionate causes. During America's antebellum period, various social and political concerns attracted wealthy men's attentions; for example, temperance advocates, a popular cause during this era, considered alcohol a sin to be abolished. One outrageous evil, southern slavery, tightly concentrated many men's political attentions, both for and against slavery. and produced some intriguing, radical rhetoric and actions; foremost among these reform movements stood abolitionism, possibly one of the greatest reform movements of this era. Among abolitionists, slavery prompted various modes of action, from moderate, to radical, to militant methods. The moderate approach tended to favor gradualism, which assumed the inevitability of society's progress toward the abolition of slavery. Radical abolitionists regarded slavery as an unmitigated evil to be ended unconditionally, immediately, and without any compensation to slaveholders. Preferring direct, political action to publicize slavery's iniquities, radical abolitionists demanded a personal commitment to the movement as a way to effect abolition of slavery. Some militant abolitionists, however, pushed their personal commitment to the extreme. Perceiving politics as a hopelessly ineffective method to end slavery, this fringe group of abolitionists endorsed violence as the only way to eradicate slavery. 1 One abolitionist, Gerrit Smith, a wealthy landowner, lived in Peterboro, New York. As a young man, he inherited from his father hundreds of thousands of acres, and in the 1830s, Smith reportedly earned between $50,000 and $80,000 annually on speculative leasing investments. -

Cloudsplitter

Reading Guide Cloudsplitter By Russell Banks ISBN: 9780060930868 Plot Summary Owen Brown, an old man wracked with guilt and living alone in the California hills, answers a query from an historian who is writing about the life and times of Owen's famous abolitionist father, John Brown. In an effort to release the demons of his past so that he can die in peace, Owen casts back his memory to his youth, and the days of the Kansas Wars which led up to the raid on Harper's Ferry. As he begins describing his childhood in Ohio, in Western Pennsylvania, and in the mountain village of North Elba, NY, Owen reveals himself to be a deeply conflicted youth, one whose personality is totally overshadowed by the dominating presence of his father. A tanner of hides and an unsuccessful wholesaler of wool, John Brown is torn between his yearnings for material success and his deeply passionate desire to rid the United States of the scourge of slavery. Having taken an oath to God to dedicate his life and the lives of his children to ending slavery, he finds himself constantly thwarted by his ever-increasing debts due to a series of disastrous business ventures. As he drags his family from farmstead to farmstead in evasion of the debt collectors, he continues his vital work on the Underground Railroad, escorting escaped slaves into Canada. As his work brings him into contact with great abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and other figures from that era, Brown finds his commitment to action over rhetoric growing ever more fervent. -

John Brown, Abolitionist: the Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights by David S

John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights by David S. Reynolds Homegrown Terrorist A Review by Sean Wilentz New Republic Online, 10/27/05 John Brown was a violent charismatic anti-slavery terrorist and traitor, capable of cruelty to his family as well as to his foes. Every one of his murderous ventures failed to achieve its larger goals. His most famous exploit, the attack on Harpers Ferry in October 1859, actually backfired. That backfiring, and not Brown's assault or his later apotheosis by certain abolitionists and Transcendentalists, contributed something, ironically, to the hastening of southern secession and the Civil War. In a topsy-turvy way, Brown may have advanced the anti-slavery cause. Otherwise, he actually damaged the mainstream campaign against slavery, which by the late 1850s was a serious mass political movement contending for national power, and not, as Brown and some of his radical friends saw it, a fraud even more dangerous to the cause of liberty than the slaveholders. This accounting runs against the grain of the usual historical assessments, and also against the grain of David S. Reynolds's "cultural biography" of Brown. The interpretations fall, roughly, into two camps. They agree only about the man's unique importance. Writers hostile to Brown describe him as not merely fanatical but insane, the craziest of all the crazy abolitionists whose agitation drove the country mad and caused the catastrophic, fratricidal, and unnecessary war. Brown's admirers describe his hatred of slavery as a singular sign of sanity in a nation awash in the mental pathologies of racism and bondage. -

CG's Proficiency Trophy Ready for Units, Basic and Advanced

Vol. XX FORT ORD,CRLIFORniaFRIDPVjnnUflRV 15,1960 Do. 16 Dead-Eye Miss Doesn't; CG's Proficiency Trophy Ready Has Trophy to Prove It Don't look now men, but a girl has been acknowledged as For Units, Basic and Advanced the best junior rifle shot at Fort Ord! In ceremonies held recently at Fort Ord's indoor rifle range, The seemingly endless debate as to which of Fort Ord's basic combat training and advanced Maj Gen Carl F. Rritzsche, commanding general of Fort Ord, infantry training companies is best will be settled—at least temporarily—this month. presented Daryl Evans with the Commanding General's Junior Operations section (G-3) is currently reviewing the over-all proficiency scores of 45 com Rifle Trophy for 1959. <f panies of the 1st and 3d Brigades in order to determine the first winner of the Commanding To gain the trophy in the pre- that if you can do it in six matches General's Proficiency Trophy which was established last September. dominently male sport, 11-year- you can also do it in five, Daryl Twenty companies of the 1st Bri old Daryl had to out-shoot 59 walked off with the Fort Ord Rod gade and 25 companies of the 3d Bri boys and three girls of the Fort and Gun Club Trophy for the best Promotions Tight gade vied during the recently com Ord Rod and Gun Club's Junior average score in five registered mat pleted training cycles for the honor Rifle Team. She did so by main ches: this time she averaged 91.43. -

“Blessings of Liberty” for All: Lysander Spooner's Originalism

SECURING THE “BLESSINGS OF LIBERTY” FOR ALL: LYSANDER SPOONER’S ORIGINALISM Helen J. Knowles* ABSTRACT On January 1, 1808, legislation made it illegal to import slaves into the United States.1 Eighteen days later, in Athol, Massachusetts, Ly- sander Spooner was born. In terms of their influence on the abolition of * Assistant Professor of Political Science, State University of New York at Oswego; B.A., Liverpool Hope University College; Ph.D., Boston University. This article draws on material from papers presented at the annual meetings of the Northeastern Political Science Association and the New England Historical Association, and builds on ideas originally discussed at the Institute for Constitutional Studies (ICS) Summer Seminar on Slavery and the Constitution and an Institute for Humane Studies An- nual Research Colloquium. For their input on my arguments about Lysander Spooner’s constitutional theory, I am grateful to Nigel Ashford, David Mayers, Jim Schmidt, and Mark Silverstein. Special thanks go to Randy Barnett who, several years ago, introduced me to Spooner, the “crusty old character” (as someone once described him to me) with whom I have since embarked on a fascinating historical journey into constitutional theory. I am also indebted to the ICS seminar participants (particularly Paul Finkelman, Maeva Marcus, and Mark Tushnet) for their comments and suggestions and to the participants in the Liberty Fund workshop on Lysander Spooner’s theories (particularly Michael Kent Curtis and Larry Solum) for prompting me to think about Spooner’s work in a variety of different ways. Finally, I would like to thank the staff of the American Antiquarian Society, the Rare Books Department of the Boston Public Library, and the Houghton Library and University Archives at Harvard University for their excellent research assistance. -

John Brown: Villain Or Hero? by Steven Mintz

John Brown: Villain or Hero? by Steven Mintz John Brown, ca. June 1859, four months before his raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. (Gilder Lehrman Collection) In 1856, three years before his celebrated raid on Harpers Ferry, John Brown, with four of his sons and three others, dragged five unarmed men and boys from their homes along Kansas’s Pottawatomie Creek and hacked and dismembered their bodies as if they were cattle being butchered in a stockyard. Two years later, Brown led a raid into Missouri, where he and his followers killed a planter and freed eleven slaves. Brown’s party also absconded with wagons, mules, harnesses, and horses—a pattern of plunder that Brown followed in other forays. During his 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, seventeen people died. The first was a black railroad baggage handler; others shot and killed by Brown’s men included the town’s popular mayor and two townsfolk. In the wake of Timothy McVeigh’s attack on the federal office building in Oklahoma City in 1995 and al Qaeda’s strikes on the World Trade Center and Pentagon in 2001, Americans might ask how they should remember John Brown. Was he a bloodthirsty zealot, a vigilante, a terrorist, or a madman? Or was he one of the great heroes of American history, a freedom fighter and martyr to the cause of human liberty? Was his resort to violence any different from, for example, those by Paul Hill and John Salvi, who, in the mid-1990s, murdered abortion-clinic workers in God’s name? Nearly a century and a half after his execution, John Brown remains one of the most fiercely debated and enigmatic figures in American history. -

The Subject of My Paper Is on the Abolitionist Movement and Gerrit Smith’S Tireless Philanthropic Deeds to See That Slavery Was Abolished

The subject of my paper is on the Abolitionist movement and Gerrit Smith’s tireless philanthropic deeds to see that slavery was abolished. I am establishing the reason I believe Gerrit Smith did not lose his focus or his passion to help the cause because of his desire to help mankind. Some historians failed to identify with Smith’s ambition and believed over a course of time that he lost his desire to see his dream of equality for all people to be realized. Gerrit Smith was a known abolitionist and philanthropist. He was born on March 6, 1797 in Utica, New York. His parents were Peter Smith and Elizabeth Livingston. Smith’s father worked as a fur trader alongside John Jacob Astor. They received their furs from the Native Americans from Oneida, Mohawk, and the Cayuga tribes in upstate New York.1 Smith and his family moved to Peterboro, New York (Madison County) in 1806 for business purposes. Gerrit was not happy with his new home in Peterboro.2 Smith’s feelings towards his father were undeniable in his letters which indicated harsh criticism. It is clear that Smith did not have a close bond with his father. This tense relationship with his father only made a closer one with his mother. Smith described him to be cold and distant. The only indication as to why Smith detested his father because he did not know how to bond with his children. Smith studied at Hamilton College in 1814. This was an escape for Smith to not only to get away from Peterboro, but to escape from his father whom he did not like. -

146 Kansas History Kansas Literature and Race

An unidentified African American woman in Topeka in the 1860s. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 36 (Autumn 2013): 146–57 146 Kansas History Kansas Literature and Race by Thomas Fox Averill ansas writers have always had, and rightfully, an ambivalence about race. What else to expect in a place known as Free State Kansas and Bleeding Kansas, but where segregation—at school, work, facilities—was the norm by 1900? What else to expect in a place associated with fiery abolitionist John Brown, but also with rampant Ku Klux Klanism by the 1920s, a half century later? What else to expect in a state that was the chosen destination of the first African American migration from the South after Reconstruction failed—the Exoduster Kmovement—but came to be known, among blacks at least, as a border, even a southern, state? What else to expect in a state that attracted educated blacks and early on elected African Americans to office, but also lynched at least nineteen blacks between 1880 and 1930? What else to expect in a state that gave more lives and suffered more wounds than any other (per capita) in the Union Army during the Civil War, that was decidedly Republican in part because it was so heavily settled by Union Army veterans, but ended up both the home of segregated Nicodemus, the first all-black settlement in the west, with its positive associations, and Tennessee Town and the Brown v. Board desegregation lawsuit in negatively segregated Topeka?1 Thomas Fox Averill is writer-in-residence and professor of English at Washburn University in Topeka, where he teaches creative writing and courses in Kansas literature, folklore, and film. -

'BEMHS^NI^ Tts

'BEMHS^NI^ Tts S 1 mm ;.i\ ' Bk>< 7 r >-' • . Bf f* ft^lipV. '••! -^•^ ? '"' m m w "•- 4 I 41 OMGQOA OFFICIAL STATE PUBLICATION VOL. XIX—No. 5 MAY, 1950 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE PENNSYLVANIA FISH COMMISSION Division of HON. JAMES H. DUFF, Governor ..a PUBLICITY and PUBLIC RELATIONS * J. Allen Barrett Director PENNSYLVANIA FISH COMMISSION MILTON L PEEK, President RADNOR PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER BERNARD S. HORNE, Vice-President PITTSBURGH South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. WILLIAM D. BURK MELROSE PARK 10 Cents a Copy—50 Cents .» Year GEN. A. H. STACKPOLE DAUPHIN Subscriptions should be addressed to the Editor, PENNSYL VANIA ANGLER, South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. Submit fee either by check or money order payable to the Commonwealth PAUL F. BITTENBENDER of Pennsylvania. Stamps not acceptable. Individuals sending cash WILKES-BARRE do so at their own risk. CLIFFORD J. WELSH ERIE PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER welcomes contributions and photos of catches from its readers. Proper credit will be given to con LOUIS S. WINNER tributors. Send manuscripts and photos direct to the Editor LOCK HAVEN PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER, South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. * Entered as Second Class matter at the Post Office of Harris EXECUTIVE OFFICE burg, Pa., under act of March 3, 1873. C. A. FRENCH, Executive Director ELLWOOD CITY IMPORTANT! H. R. STACKHOUSE The ANGLER should be notified immediately of change in sub Adm. Secretary scriber's address. Send both old and new addresses to Pennsyl vania Fish Commission, South Office Building, Harrisburg, Pa. * Permission to reprint will be granted if proper credit is given. C. R. BULLER Chief Fish Culturist THOMAS F. -

Rise Now and Fly to Arms : the Life of Henry Highland Garnet

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1981 Rise now and fly ot arms : the life of Henry Highland Garnet. Martin B. Pasternak University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Pasternak, Martin B., "Rise now and fly ot arms : the life of Henry Highland Garnet." (1981). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1388. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1388 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS/AMHERST 312Qbt.D13S7H35a RISE NOW AND FLY TO ARMS : THE LIFE OF HENRY HIGHLAND GARNET A Dissertation Presented By MARTIN B. PASTERNAK Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 1981 HISTORY Martin B. Pasternak 1981 All Rights Reserved 11I : RISE NOW AND FLY TO ARMS THE LIFE OF HENRY HIGHLAND GARNET A Dissertation Presented By Martin B. Pasternak Approved as to style and content by: i Stephen B . Gates , Chairperson of Committee David Wyman, Membet Sidney Kapl any Member Leonard L Richards , Department Head History PREFACE Historian Paul Murray Kendall called the art of biography the continuing struggle of life-writing. The task of bringing the relatively obscure Garnet to life was difficult, but no biographer could have asked for a more complicated and exciting subject.