Reflection Essay: Designs on Signs: Myth and Meaning in Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cartographic Perspectives Information Society 1

Number 53, Winterjournal 2006 of the Northcartographic American Cartographic perspectives Information Society 1 cartographic perspectives Number 53, Winter 2006 in this issue Letter from the Editor INTRODUCTION Art and Mapping: An Introduction 4 Denis Cosgrove Dear Members of NACIS, FEATURED ARTICLES Welcome to CP53, the first issue of Map Art 5 Cartographic Perspectives in 2006. I Denis Wood plan to be brief with my column as there is plenty to read on the fol- Interpreting Map Art with a Perspective Learned from 15 lowing pages. This is an important J.M. Blaut issue on Art and Cartography that Dalia Varanka was spearheaded about a year ago by Denis Wood and John Krygier. Art-Machines, Body-Ovens and Map-Recipes: Entries for a 24 It’s importance lies in the fact that Psychogeographic Dictionary nothing like this has ever been kanarinka published in an academic journal. Ever. To punctuate it’s importance, Jake Barton’s Performance Maps: An Essay 41 let me share a view of one of the John Krygier reviewers of this volume: CARTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES …publish these articles. Nothing Cartographic Design on Maine’s Appalachian Trail 51 more, nothing less. Publish them. Michael Hermann and Eugene Carpentier III They are exciting. They are interest- ing: they stimulate thought! …They CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS are the first essays I’ve read (other Illinois Historical Aerial Photography Digital Archive Keeps 56 than exhibition catalogs) that actu- Growing ally try — and succeed — to come to Arlyn Booth and Tom Huber terms with the intersections of maps and art, that replace the old formula REVIEWS of maps in/as art, art in/as maps by Historical Atlas of Central America 58 Reviewed by Mary L. -

WHAT MAKES a MAP a MAP? North Carolina State University, Raleigh

81 WHAT MAKES A MAP A MAP? DENIS WOOD North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, United States Abstract Cartographers have long pretended that the authority structure of the world expressed in map form," where of the map was a function of its resemblance to the world. Hence "map" was to be taken, "in the concrete sense of the con cartographers' obsessive concern with accuracy. Here it is argued ventional map, so that the products resemble that the map's power derives from the audiority the map steals maps."'Distinguishing among six hypothesized map from its maker. types, I characterized this standard map as, "what we are used to calling a map," going on to note that such a map, What makes a map a map? It is its mask that makes it "can be acquired at any gas station free or purchased in a map, its mask of detached neutrality, of unbiased com book stores or found bound into atlases."2 prehensiveness. Why does the map wear this mask? Not That is, we were at pains to distinguish among three as it might be imagined to obscure a blemish, but because things: a map (the concrete artifact available at gas sta it finds itself in a situation never meant to be. This is tions), an experimental sketch map (a maplike sketch- true of all alienated sign systems, they have become un product created by people in an experimental setting), and moored from the dock of human intercourse, they are a mental map (the presumed neural medium for purpose floating on a turbulent stream, objects in the world, but ful action in the world). -

Public Taste: a Comparison of Movie Popularity and Critical Opinion

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 Public taste: A comparison of movie popularity and critical opinion R. Claiborne Riley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Riley, R. Claiborne, "Public taste: A comparison of movie popularity and critical opinion" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625207. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-hqz7-rj05 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLIC TASTE: A COMPARISON OF MOVIE u POPULARITY AND CRITICAL OPINION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology The College of William, and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by R. Claiborne Riley 1982 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts R. Claiborne Riley Approved, September 1982 r**1. r i m f Satoshi Ito JL R. Wayne Kernodle Marion G. Vanfossen TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......... iv LIST OF TABLES . ..... .... ..................... v ABSTRACT .......... '......... vi INTRODUCTION .......... ...... 2 Chapter I. THE MOVIES: AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE .............. 6 Chapter II. THE AUDIENCE ........................................ 51 Chapter III. THE C R I T I C ............ 61 Chapter IV. THE WANDERER STUDY AND DUMAZEDIER ON MOVIES AND LEISURE ....... -

The Golden Age of Statistical Graphics

The Golden Age of Statistical Graphics Michael Friendly Psychology Department and Statistical Consulting Service York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M3J 1P3 in: Statistical Science. See also BIBTEX entry below. BIBTEX: @Article{Friendly:2008:golden, author = {Michael Friendly}, title = {The {Golden Age} of Statistical Graphics}, journal = {Statistical Science}, year = {2008}, volume = {}, number = {}, pages = {}, url = {http://www.math.yorku.ca/SCS/Papers/golden.pdf}, note = {in press (accepted 8-Sep-08)}, } © copyright by the author(s) document created on: September 8, 2008 created from file: golden.tex cover page automatically created with CoverPage.sty (available at your favourite CTAN mirror) In press, Statistical Science The Golden Age of Statistical Graphics Michael Friendly∗ September 8, 2008 Abstract Statistical graphics and data visualization have long histories, but their modern forms began only in the early 1800s. Between roughly 1850 to 1900 ( 10), an explosive oc- curred growth in both the general use of graphic methods and the range± of topics to which they were applied. Innovations were prodigious and some of the most exquisite graphics ever produced appeared, resulting in what may be called the “Golden Age of Statistical Graphics.” In this article I trace the origins of this period in terms of the infrastructure required to produce this explosive growth: recognition of the importance of systematic data collection by the state; the rise of statistical theory and statistical thinking; enabling developments -

Click to Download

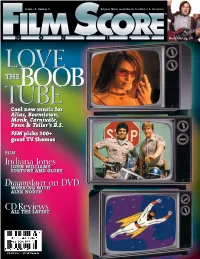

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

Corvette Summer Torrent Download a TORRENTS

corvette summer torrent download A TORRENTS. Corvette Summer (1978) (1080p BluRay X265 HEVC 10bit AAC 2.0 Qman) [UTR] Uploaded at: Jan. 22, 2021. Corvette Summer (1978).1080p.BluRay.x265.10bit.AAC.2.0-Qman[UTR].mkv (5.9 GB) Media Information Code:General Format : Matroska Format version : Version 4 / Version 2 File size : 5.89 GiB Duration : 1 h 44 min Overall bit rate : 8 057 kb/s Encoded date : UTC 2021-01-21 17:56:06 Writing application : mkvmerge v51.0.0 ('I Wish') 64-bit Writing library : libebml v1.4.0 + libmatroska v1.6.2 Video ID : 1 Format : HEVC Format/Info : High Efficiency Video Coding Format profile : Main [email protected]@Main Codec ID : V_MPEGH/ISO/HEVC Duration : 1 h 44 min Bit rate : 7 969 kb/s Width : 1 920 pixels Height : 1 080 pixels Display aspect ratio : 16:9 Frame rate mode : Constant Frame rate : 23.976 (24000/1001) FPS Color space : YUV Chroma subsampling : 4:2:0 Bit depth : 10 bits Bits/(Pixel*Frame) : 0.160 Stream size : 5.82 GiB (99%) Writing library : x265 3.2+23-52135ffd9bcd:[Windows][GCC 9.2.1] [64 bit] 10bit Encoding settings : cpuid=1111039 / frame-threads=4 / numa-pools=16 / wpp / no-pmode / no-pme / no-psnr / no-ssim / log- level=2 / input-csp=1 / input-res=1920x1080 / interlace=0 / total-frames=150485 / level-idc=0 / high-tier=1 / uhd-bd=0 / ref=4 / no-allow-non- conformance / no-repeat-headers / annexb / no-aud / no-hrd / info / hash=0 / no-temporal-layers / open-gop / min-keyint=23 / keyint=250 / gop- lookahead=0 / bframes=8 / b-adapt=2 / b-pyramid / bframe-bias=0 / rc-lookahead=80 / lookahead-slices=4 -

3D Visualization of Cadastre: Assessing the Suitability of Visual Variables and Enhancement Techniques in the 3D Model of Condominium Property Units

3D Visualization of Cadastre: Assessing the Suitability of Visual Variables and Enhancement Techniques in the 3D Model of Condominium Property Units Thèse Chen Wang Doctorat en sciences géomatiques Philosophiæ doctor (Ph.D.) Québec, Canada © Chen Wang, 2015 3D Visualization of Cadastre: Assessing the Suitability of Visual Variables and Enhancement Techniques in the 3D Model of Condominium Property Units Thèse Chen Wang Sous la direction de : Jacynthe Pouliot, directrice de recherche Frédéric Hubert, codirecteur de recherche Résumé La visualisation 3D de données cadastrales a été exploitée dans de nombreuses études, car elle offre de nouvelles possibilités d’examiner des situations de supervision verticale des propriétés. Les chercheurs actifs dans ce domaine estiment que la visualisation 3D pourrait fournir aux utilisateurs une compréhension plus intuitive d’une situation où des propriétés se superposent, ainsi qu’une plus grande capacité et avec moins d’ambiguïté de montrer des problèmes potentiels de chevauchement des unités de propriété. Cependant, la visualisation 3D est une approche qui apporte de nombreux défis par rapport à la visualisation 2D. Les précédentes recherches effectuées en cadastre 3D, et qui utilisent la visualisation 3D, ont très peu enquêté l’impact du choix des variables visuelles (ex. couleur, style) sur la prise de décision. Dans l’optique d'améliorer la visualisation 3D de données cadastres, cette thèse de doctorat examine l’adéquation du choix des variables visuelles et des techniques de rehaussement associées afin de produire un modèle de condominium 3D optimal, et ce, en fonction de certaines tâches spécifiques de visualisation. Les tâches visées sont celles dédiées à la compréhension dans l’espace 3D des limites de propriété du condominium. -

In This Issue 15Th General Assembly of Ica President's Report

www.icaci.org biannual newsletter | number :: numéro 55 | december :: dècembre 2010 president’s report in this issue Dear Colleagues bles the complete newsletter and generates a This December 2010 PDF file. After it is checked and approved, Igor president’s report :: 01 issue of the newsletter generates two PDF versions for placing on the is published to again website – one for screen viewing and another for download and print. ICA Web masters Felix 15th general assembly bring the ICA commu- Ortag and Manuela Schmidt, at TU Wien in of ica :: 01 nity up-to-date with the Vienna, Austria then place these two PDF files activities that have onto the ICA wesite. In parallel, another digital from the editor :: 02 taken place that are version of the newsletter is transferred associated with the electronically by Igor to a printer in Hong Kong, Association, as well as providing complemen- 25th international cartographic where, initially, a proof is output for review. tary information that will be of interest to conference 2011 :: 04 This proof is checked by Hong Kong-based ICA friends of ICA. Editor, Igor Drecki is to be again Vice President Professor Zhilin Li. After congratulated with the publication of another ica news approval the newsletters are printed and great issue. dispatched to Professor Li who, with the children’s map award 2011 :: 03 It is worth noting how Igor is using the global assistance of students at the Hong Kong ica executive committee :: 04 reach of the Association to streamline the Polytechnic University, place the newsletters in ica news contributions :: 04 production, printing and distribution of the envelopes, which are then mailed from Hong 25 years ago.. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

A Brief History of Data Visualization

A Brief History of Data Visualization Michael Friendly Psychology Department and Statistical Consulting Service York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M3J 1P3 in: Handbook of Computational Statistics: Data Visualization. See also BIBTEX entry below. BIBTEX: @InCollection{Friendly:06:hbook, author = {M. Friendly}, title = {A Brief History of Data Visualization}, year = {2006}, publisher = {Springer-Verlag}, address = {Heidelberg}, booktitle = {Handbook of Computational Statistics: Data Visualization}, volume = {III}, editor = {C. Chen and W. H\"ardle and A Unwin}, pages = {???--???}, note = {(In press)}, } © copyright by the author(s) document created on: March 21, 2006 created from file: hbook.tex cover page automatically created with CoverPage.sty (available at your favourite CTAN mirror) A brief history of data visualization Michael Friendly∗ March 21, 2006 Abstract It is common to think of statistical graphics and data visualization as relatively modern developments in statistics. In fact, the graphic representation of quantitative information has deep roots. These roots reach into the histories of the earliest map-making and visual depiction, and later into thematic cartography, statistics and statistical graphics, medicine, and other fields. Along the way, developments in technologies (printing, reproduction) mathematical theory and practice, and empirical observation and recording, enabled the wider use of graphics and new advances in form and content. This chapter provides an overview of the intellectual history of data visualization from medieval to modern times, describing and illustrating some significant advances along the way. It is based on a project, called the Milestones Project, to collect, catalog and document in one place the important developments in a wide range of areas and fields that led to mod- ern data visualization. -

Principles of Data Visualization

Lecture 3: Principles of Data Visualization Instructor: Saravanan Thirumuruganathan CSE 5334 Saravanan Thirumuruganathan Outline 1 Bertin's Visual Attributes 2 Tufte's Principles 3 Effective Visualization 4 Intro to PsychoPhysics CSE 5334 Saravanan Thirumuruganathan In-Class Quizzes URL: http://m.socrative.com/ Room Name: 4f2bb99e CSE 5334 Saravanan Thirumuruganathan Announcements One-time attendance recording Form teams soon! Programming Assignment 1 will be released this weekend (due in 3 weeks) CSE 5334 Saravanan Thirumuruganathan Bertin's Visual Attributes CSE 5334 Saravanan Thirumuruganathan �������������� � �������������������� ����������� � ���������������������� ������ � ����������������������� �������������������� �������������������������� ����� ������ ����� ����� �������� �������� ���� ����������� ������� ����� ����������� ����� ����������������������������������� ������������������� ������������������ ��������������������������������� ����������������������������� ������� ������������ ���� ������� ���������������� �������������������� ������������������������������� ������������ ���� ���������������������� ��������� ������������ ������������������������ ��������������� ����������������������������������� �������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������� ������������������������������� ������������������������������ ������������������������������������ ��� ��������������������������������������� ����� �������� } ������������ } ������� ������ �������� } ������� ������������� ������������������������ -

June 2020June 2020

Legends Ledger JuneJune 20202020 June Meeting Rare Member Sighting... Willie George in his Red 1962. Photo taken at the Legends Club Photo Day at the Cavanaugh Flight Museum in 2010 CANCELLED! Jun 7-13 Hot Rod Power Tour Norwalk, OH-Joliet, IL Rescheduled to August 23-29, 2020 *June 13 Legends Club Meeting 11:00 AM -- 2020 Cancelled Do this instead!> June 13 Parker Square Car Show 4-8 pm Flower Mound, TX 1400 Cross Timbers Rd (FM 1171), 3 mi west of I-35 between Garden Ridge & Morriss. Upcoming Car Shows on the 2nd Sat. of each month Jun & Aug 4-8pm, Sept & Oct 3-6pm, Nov 2:30-6pm. Sponsored by North Texas Mustang Club, http://www.ntmc.org/, All makes of cars welcome. Events June 13 NCCO All-Corvette Show Embassy Suites Norman, OK Cancelled June 20 Conner’s Car Show & Keller Crawfish Krawl Keller, TX Top 100 Show. 11am-4pm. Keller Town Hall, 1100 Bear Creek Pkwy. Live & silent auctions, live music, food, over 100 vendors, shopping & restaruants, and more. All car types and styles welcome. Benefits Downs Syndrome and Autism charities. Info: connerscarshow.com July 10-12 Corvette Kickoff Classic Apache Casino Hotel Lawton, OK This is a New Date-Details on Pg. 10 *July 11 Legends Club Meeting July 17-19 Corvette Invasion Bastrop Convention Center Bastrop, TX Details on page 4 *CLoT Club Participation Event July 19-23 NCRS National Convention French Lick, IN Cancelled *Aug 8 Legends Club Meeting 11:00 AM Aug 21-22 Summer’s End Corvette Show Springdale/Rogers, AR Details on Pg.