Mechanism and Management of the Dumping Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Pancreatectomy for Chronic Pancreatitis

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.29.3.358 on 1 March 1988. Downloaded from Gut, 1988, 29, 358-365 Total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis I P LINEHAN, M A LAMBERT, D C BROWN, A B KURTZ, P B COTTON, AND R C G RUSSELL From the Departments ofSurgery, Gastroenterology and Medicine, The Middlesex Hospital and Medical School, London SUMMARY The operation oftotal pancreatectomy is performed rarely. Its role in the management of patients with chronic pancreatitis remains to be elucidated. We have reviewed our series of 29 total pancreatectomies for benign disease [14 women median age 39 years; 15 men median age 34 years]. Twelve underwent standard total pancreatectomy, in 17 duodenum preserving total pancreatectomy (DPTP) was performed. There was one death (mortality 3.4%). In no patient was the total pancreatectomy the first operative procedure. The patients were compared with age and sex matched diabetic control subjects selected on a best fit basis from the diabetic clinic database. The aetliology of the pancreatitis was idiopathic nine, pancreas divisum nine, alcohol eight and other causes three. The indication for surgery was pain 27, acute pancreatitis one and cholangitis with pancreatitis one. The complications ofthe procedures were mainly caused by infection [wound three, chest six and central line sepsis four] and in two there was a leak from the duodenum; no patient required re-operation. The postoperative stay [standard total, median 21 days (range 13-98) DPTP median 31 days (range 17-49)] has lengthened over the period due to greater attention to analgesic, diabetic and enzyme deficiency control before discharge. -

Gastroparesis and Dumping Syndrome: Current Concepts and Management

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Gastroparesis and Dumping Syndrome: Current Concepts and Management Stephan R. Vavricka 1,2,* and Thomas Greuter 2 1 Center of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, CH-8048 Zurich, Switzerland 2 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospital Zurich, CH-8091 Zurich, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 21 June 2019; Accepted: 23 July 2019; Published: 29 July 2019 Abstract: Gastroparesis and dumping syndrome both evolve from a disturbed gastric emptying mechanism. Although gastroparesis results from delayed gastric emptying and dumping syndrome from accelerated emptying of the stomach, the two entities share several similarities among which are an underestimated prevalence, considerable impairment of quality of life, the need for a multidisciplinary team setting, and a step-up treatment approach. In the following review, we will present an overview of the most important clinical aspects of gastroparesis and dumping syndrome including epidemiology, pathophysiology, presentation, and diagnostics. Finally, we highlight promising therapeutic options that might be available in the future. Keywords: gastroparesis; dumping syndrome; pathophysiology; clinical presentation; treatment 1. Introduction Gastroparesis and dumping syndrome both evolve from a disturbed gastric emptying mechanism. While gastroparesis results from significantly delayed gastric emptying, dumping syndrome is a consequence of increased flux of food into the small bowel [1,2]. The two entities share several important similarities: (i) gastroparesis and dumping syndrome are frequent, but also frequently overlooked; (ii) they affect patient’s quality of life considerably due to possibly debilitating symptoms; (iii) patients should be taken care of within a multidisciplinary team setting; and (iv) treatment should follow a step-up approach from dietary modifications and patient education to pharmacological interventions and, finally, surgical procedures and/or enteral feeding. -

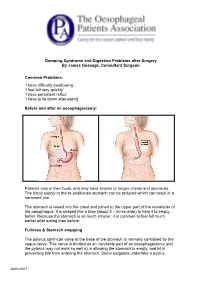

Dumping Syndrome and Digestion Problems After Surgery by James Gossage, Consultant Surgeon Common Problems: 'I Have Difficulty

Dumping Syndrome and Digestion Problems after Surgery By James Gossage, Consultant Surgeon Common Problems: ‘I have difficulty swallowing’. ‘I feel full very quickly’ ‘I have persistent reflux’ ‘I have to lie down after eating’ Before and after an oesophagectomy: Patients vary in their build, and may have shorter or longer chests and stomachs. The blood supply to the re-positioned stomach can be reduced which can result in a narrowed join. The stomach is raised into the chest and joined to the upper part of the remainder of the oesophagus. It is shaped like a tube (about 5 – 6cms wide) to help it to empty better. Because the stomach is so much smaller, it is common to feel full much earlier after eating than before. Fullness & Stomach emptying The pylorus sphincter valve at the base of the stomach is normally controlled by the vagus nerve. This nerve is divided as an inevitable part of an oesophagectomy and the pylorus may not work so well a) in allowing the stomach to empty, and b) in preventing bile from entering the stomach. Some surgeons undertake a pyloric 26/01/2017 myotomy (cutting the muscles to increase its capacity) as part of the main surgery; others prefer to wait and see if a problem develops, and then treat it by stretching it with an endoscope. Difficulty in Swallowing: Difficulty in Swallowing Narrow join Acid reflux leading to inflammation Fungal infection (candidiasis) Treatment options can be: Endoscopic dilation – acid suppression – sucralfate (binds the stomach) – antifungals Motility agents (domperidone, metoclopramide (good anti-sickness medication but needs 6 weeks to be fully effective; erythromycin). -

Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders

Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders Jassin M. Jouria, MD Dr. Jassin M. Jouria is a medical doctor, professor of academic medicine, and medical author. He graduated from Ross University School of Medicine and has completed his clinical clerkship training in various teaching hospitals throughout New York, including King’s County Hospital Center and Brookdale Medical Center, among others. Dr. Jouria has passed all USMLE medical board exams, and has served as a test prep tutor and instructor for Kaplan. He has developed several medical courses and curricula for a variety of educational institutions. Dr. Jouria has also served on multiple levels in the academic field including faculty member and Department Chair. Dr. Jouria continues to serve as a Subject Matter Expert for several continuing education organizations covering multiple basic medical sciences. He has also developed several continuing medical education courses covering various topics in clinical medicine. Recently, Dr. Jouria has been contracted by the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital’s Department of Surgery to develop an e-module training series for trauma patient management. Dr. Jouria is currently authoring an academic textbook on Human Anatomy & Physiology. Abstract The muscles of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract perform an important job. The GI tract peristalsis, or contractions, mix the contents of the stomach and propel contents throughout the entire GI tract until they exit as waste. When these muscles underperform or fail to perform, it can create serious and painful consequences, diagnosed as GI motility disorders. Although these disorders are rarely fatal, they can cause physical and emotional effects that negatively impact a patient's quality of life. -

Ocreotide and Its Effects on Steroid Resistant Crohn's Disease

2ND YEAR RESEARCH ELECTIVE RESIDENT’S JOURNAL Volume III, 1998-1999 Octreotide and its effects on Steroid resistant Crohn’s Disease Bonnie Wolf A. Introduction The treatment of Crohn’s disease continues to be a challenge as its pathogenesis remains obscure. Compounded by the increased incidence of Crohn's disease in the past twenty years incidence of 5/100,000, prevalence of 50/100,000), we are faced with an ever increasing number of treatment failures. The pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease stems from a dysregulation of the immune system, with persistent amplification of inflammatory cytokines, ultimately leading to tissue destruction and disease. Conventional treatment continues to be sulphasalazine or 5-ASA and glucocorticoids. For early disease and maintenance therapy, these medications have proven to be satisfactory and widely tolerated. Yet by the nature of this disease, patients relapse. They require increasing doses of medications thereby becoming resistant and simultaneously developing side effects. Sulphasalazine was shown to be more effective than placebo in controlling active disease, but was not as efficacious as steroids (2,3). In addition, not all patients can tolerate 5-ASA secondary to mild side effects including diarrhea, dizziness, nausea, and headache. Glucocorticoids are still considered to be very effective and are the most popular prescribed medications for acute active disease. The National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study showed that 47% of patients achieved remission and 60% improvement under therapy with varying doses of prednisilone. (2) Despite it effectiveness, glucocorticoids have a wide and significant side effect profile, and are considered unsafe to be used with frequent exacerbations and moreover as maintenance therapy.(1) Most recently, immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine (Imuran) and Purinethanol (6- mercaptopurine.) have been introduced as potential therapies for patients who have chronic active disease or who are steroid dependent. -

Post-Whipple: a Practical Approach to Nutrition Management

NINFLAMMATORYUTRITION ISSUES BOWEL IN GASTROENTEROLO DISEASE: A PRACTICALGY, SERIES APPROACH, #108 SERIES #73 Carol Rees Parrish, M.S., R.D., Series Editor Post-Whipple: A Practical Approach to Nutrition Management Nora Decher Amy Berry The classic pancreatoduodenectomy (PD), also known as the Kausch-Whipple, and the pylorus- preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD) are most commonly performed for treatment of pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. This highly complex surgery disrupts the coordination of tightly orchestrated digestive processes. This, in combination with a diseased gland, sets the patient up for nutritional complications such as altered motility (gastroparesis and dumping), pancreatic insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, nutritional deficiencies and bacterial overgrowth. Close monitoring and attention to these issues will help the clinician optimize nutritional status and help prevent potentially devastating complications. 63-year-old female, D.D., presented to the copper, zinc, selenium, and potentially thiamine University of Virginia Health System (UVAHS) (thiamine was repleted before serum levels were Awith weight loss and biliary obstruction. She was checked). A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with diagnosed with a large pancreatic serous cystadenoma jejunal extension (PEG-J) was placed due to intolerance and underwent a pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) of gastric enteral nutrition (EN). After several more (standard Whipple procedure with partial gastrectomy) hospitalizations, prolonged rehabilitation in a nursing with posterior anastomosis and cholecystectomy. Seven home, 7 months of supplemental nocturnal EN, and months later she was admitted to UVAHS with nausea, treatment of pancreatic insufficiency with pancreatic vomiting, diarrhea and a severe weight loss of 47lbs enzymes (with her meals and EN), D.D. was able to (33% of her usual body weight). -

Dumping Syndrome Diet

4 The Dumping Syndrome Diet What foods can I eat after stomach surgery? Foods in the “Recommended” list are usually well tolerated after stomach surgery. Remember to drink unsweetened liquids 30 to 60 minutes after eating solid foods. Type of Food Recommended Avoid Milk and milk Milk, plain yogurt, artificially Sweetened milk, chocolate milk, The Dumping Syndrome Diet products sweetened yogurt, cottage milkshakes, sweetened condensed cheese, cream cheese, sugar free milk; ice cream, puddings, custard, pudding, cheese, cream soups fruit flavoured yogurt, frozen yogurt After a stomach resection, you may feel sick when you finish your meal. Breads and Whole wheat breads, whole wheat Cereals with a sugar coating, granola, You will need to make some changes to your diet while your body heals cereals pasta, unsweetened cereals, sweet breads, rolls, cakes, cookies, after surgery. potatoes, rice, crackers, pretzels sweet baked goods, pancakes and Esophagus waffles with syrup, doughnuts Meats and Meat, poultry, fish, eggs, lunch Casseroles and dishes prepared with Bile Duct alternatives meat, tofu, peanut butter, nuts, sweet sauces legumes Fruits and Fruits – fresh fruit, unsweetened Canned fruit in syrup, sweetened fruit Duodenum Stomach vegetables canned or frozen fruit, juice, dried fruit Jejunum unsweetened fruit juice Vegetables cooked in sweet sauces Vegetables – all types Fats and oils Butter, margarine, oil, salad None Bile dressings Beverages All unsweetened drinks such as Sweetened drinks like Kool-aid, (limit to 4 oz Crystal Light, water, -

The British Society of Gastroenterology

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.12.10.853 on 1 October 1971. Downloaded from Gut, 1971, 12, 853-870 The British Society of Gastroenterology The 32nd annual general meeting of the British Society of Gastroenterology was held at Newcastle upon Tyne from 23 to 25 September 1971 under the Presidency of Professor A. A. Harper. The programme included the abstracts that follow and in addition symposia on 'Aetiology and epidemiology of carcinoma of the colon and rectum' and 'Ischaemic colitis', and a progress re- port by Professor E. L. Blair on 'Measurement of gastrointestinal hormones'. A report on the business ofthe meeting is printed on page 871. Gastroenterostomy-An Obsolete Operation? Preparation and Characterization of Lateral and Basal Plasma Membranes of the Rat Enterocyte W. P. SMALL, C. W. A. FALCONER, A. N. SMITH, J. P. A, MCMANUS, AND W. SIRCUS (Gastro-Intestinal Unit, A. P. DOUGLAS, R. KERLEY, R. CORNELL, AND K. J. Western General Hospital, Edinburgh) Gastro- ISSELBACHER (Royal Postgraduate Medical School. enterostomy fell from favour once its association University of London, London, W.12, and Massa- with a high incidence of jejunal ulceration became chusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA) Ana- recognized. It has never regained popularity, tomical and physiological studies suggest there is a although some surgeons have recommended its distinct polarity in the enterocyte. These considera- further trial (Tanner, 1969) and although surgeons tions suggest there may well be differences between who could look back to the heyday of gastroentero- the plasma membrane (PM) of the brush border and stomy claimed that, when uncomplicated by jejunal that of the lateral and basal boundaries of the cell. -

What Is Dumping Syndrome? After a Gastrectomy, Food and Fluids Move Through Your Digestive System More Quickly Than Usual

UW MEDICINE | PATIENT EDUCATION | Gastrectomy Diet | | Nutrition guidelines | This handout gives eating guidelines after having a gastrectomy. Eating After Your Surgery During your surgery, your surgeon removed part or all of your stomach. For at least the first 4 to 6 weeks after your surgery, you will be able to eat and drink only soft foods. It is common to quickly feel full after this surgery. You may also have dumping syndrome, when food moves into the intestines too fast, causing diarrhea or discomfort (see page 4). The guidelines in this handout will help you get the calories and nutrients your body needs during your recovery time. Getting Started During your hospital stay after surgery, you will start with a Clear Liquid Diet then move to a Full Liquid Diet. You will eat and drink clear and full liquids such as broth, tea, water, gelatin, milk, yogurt, pudding, ice cream, milkshakes, creamy soups, and protein drinks. When you leave the hospital, you should be ready to start eating a Soft Diet. This means you will be able to eat and drink soft, moist foods. If moist, soft, solid foods are too hard to swallow, or you have nausea and belly discomfort after eating, go back to the Full Liquid Diet. When you are ready, try eating soft, moist foods again. For Best Results • Eat and drink slowly. • Cut your food into small pieces. Chew it well. • Stop eating when you feel full. At first, you may be able to eat only about ½ cup of food at a time. Eat 5 to 6 small meals during the day instead • Instead of eating 3 large meals, eat 5 to of 3 large meals. -

EDS for the Gastroenterologist

EDS for the Gastroenterologist Gastrointestinal problems are routine in patients with any of the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes (EDS), a loose term for a number of inherited conditions. These notes are brief reminders to gastroenterologists of items to keep in mind when dealing with people with an EDS. The medical literature contains numerous papers over several decades, documenting the high incidence of joint hypermobility syndromes among patients with a wide variety of gastroenterologic problems, presenting at specialist GI clinics. However, there seems to be no research on whether the diagnosis or treatment of such problems presents special features in these patients. The remarks below are therefore based on a clinical consensus of international experts, as presented at international meetings over the last several years.1 The Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes The great majority of people with an EDS have the “Classic Type” or the “Hypermobility Type”. In both these, there is marked looseness or hypermobility of joints. In the Classic Type the skin is very elastic (stretchy). In the Hypermobility Type, skin is often normal or nearly so. A rarer type is the Vascular Type, in which joint hypermobility may be minor, but there are frequent, very dangerous complications due to rupture of hollow organs, including arterial aneurysms and abdominal viscera. See below for more on this. The underlying lesion is different in different kinds of EDS. Mechanical defects in the microscopic structure of collagen are nearly always present, and in the Classic and Vascular Types can be attributed to specific gene mutations. However, in the Hypermobility Type no such genetic fault has been identified. -

Gastroparesis Part 3, Dumping Syndrome

DUMPING SYNDROME AND GASTROPARESIS-LIKE SYNDROME Gastroparesis is a chronic disease accompanied by bloating, early fullness after a meal, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. A diagnosis of Gastroparesis requires objective data demonstrating delayed gastric emptying in the absence of intestinal obstruction. There are, however, disorders known as Gastroparesis-Like Syndrome (GLS). Patients with GLS have the same or similar symptoms to those who have Gastroparesis, but on gastric emptying studies it shows normal or rapid emptying. Interestingly, both patient types, those with Gastroparesis (slowed or delayed emptying) and those with normal or rapid emptying, have been shown to benefit from Gastro-Electrical Stimulation (GES) placement. GLS may be actually be a spectrum of Gastroparesis. Patients who present with unexplained nausea and vomiting for at least 12 weeks without evidence of obstruction should be evaluated for both Gastroparesis and GLS. Chronic unexplained nausea patients may have similar abnormal scores on the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI); therefore, an objective test of gastric emptying needs to be done, such as a Scintigraphic Gastric Emptying study. For patients who have chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting on biopsy have loss of neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) and loss of Interstitial Cells of Cajal. These two findings are also seen in chronic Gastroparesis. As a quick summary, when comparing patients with Gastroparesis with delayed gastric emptying and GLS with normal or rapid emptying, they both have similar GSCI scores. The difference is in the gastric emptying study. Gastroparesis patients appear to have slow emptying and a loss of the Interstitial Cells of Cajal. However, the Cells of Cajal also decrease in GLS patients. -

Diet After Whipple Procedure (Pancreaticoduodenectomy)

Diet after Whipple Procedure (Pancreaticoduodenectomy) Patient name: Surgery date: Dietitian: Contact number: Introduction A Review of Your Digestive Tract Digestion starts in the mouth. When you chew and swallow food, it Mouth goes down the esophagus and lands in your stomach. From there, the contents move to your small bowel (also known as the small intestine). Esophagus Most digestion happens in this long and narrow muscular tube. The small bowel is where proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and vitamins are absorbed. The pancreas aids in digestion by producing pancreatic enzymes to Stomach help digest food in the small bowel. Next the contents enter your large Small bowel (also known as the large intestine or colon). The large bowel Intestine absorbs water and electrolytes, turning contents from liquid to formed bowel movements. Large Intestine What is a Whipple Procedure? A Whipple procedure also known as a Pancreaticoduodenectomy, is the surgical removal of the head of the pancreas, part of the duodenum (a portion of the small bowel), the lower bile duct, the gallbladder, and sometimes part of the stomach. Your surgeon may do the procedure in one of two ways: Standard (classic) procedure Pylorus preserving procedure Liver Bile duct Stomach Liver Bile duct Stomach Jejunum Jejunum (small intestine) (small intestine) Tail of Tail of pancreas Pylorus pancreas The surgical removal of these organs may cause some people to experience symptoms after the surgery, requiring changes to their diet. Possible Nutrition Problems and Tips Delayed Stomach Emptying (Gastroparesis) Gastroparesis is a condition where food moves through your stomach slower than normal to your small bowel.