Monsieur Lazhar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

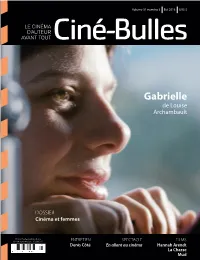

Gabrielle De Louise Archambault

Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 5,95 $ ÉTÉ 2013 Gabrielle de Louise Archambault DOSSIER Cinéma et femmes REVUE DE CINÉMA PUBLIÉE PAR L’ASSOCIATION DES CINÉMAS PARALLÈLES DU QUÉBEC VOLUME 31 NUMÉRO 3 VOLUME DU QUÉBEC PARALLÈLES DES CINÉMAS L’ASSOCIATION PUBLIÉE PAR REVUE DE CINÉMA Envoi Poste-publications No de convention : 40069242 ENTRETIEN SPECTACLE FILMS Denis Côté En allant au cinéma Hannah Arendt La Chasse Mud C0 M49 Y66 K0 Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 2 EN COUVERTURE Gabrielle 2 Entretien avec Louise Archambault SOMMAIRE 8 Commentaire critique ENTRETIEN 12 Denis Côté Scénariste et réalisateur de Vic et Flo ont vu un ours 20 Commentaire critique SPECTACLE 12 59 56 En allant au cinéma FILMS 10 Hannah Arendt de Margarethe von Trotta 58 Au-delà des collines de Cristian Mungiu 59 La Chasse de Thomas Vinterberg 60 The Great Gatsby de Baz Luhrmann 61 Mud de Je Nichols 62 Sarah préfère la course de Chloé Robichaud 10 63 This Must Be the Place de Paolo Sorrentino 23 Introduction au dossier 24 Les pionnières québécoises 28 Au Québec en 2013 38 L’horreur au féminin 42 Le combat émancipateur 46 Du masculin au féminin 50 Les lms les plus populaires 54 Coret 20 Courts et grand talent Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 RÉDACTION ÉDITION ABONNEMENT ANNUEL PAYABLE À L’ACPQ (4 NUMÉROS) Éric Perron, rédacteur en chef Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec (ACPQ) Individuel : 23 $ – Institutionnel : 45,99 $ (taxes comprises) [email protected] Martine Mauroy, directrice générale Étranger : 60 $ (non taxable) 514.252.3021 poste 3413 4545, av. -

Speech by Carolle Brabant, Quebec MBA

QUEBEC MBA ASSOCIATION APRIL 25, 2012 The Canadian audiovisual industry: We mean business Speech delivered by Carolle Brabant, C.P.A., C.A., MBA Executive Director, Telefilm Canada I’d like to thank you for being here today as well as thank the Quebec MBA Association for making culture a part of these lunch-time talks. As an MBA graduate myself, I’m delighted to be able to use this forum to speak to you about a passionate and important industry for the economic and cultural future of Canada: the audiovisual industry. I decided to join this industry over 21 years ago and I’ve never regretted it. It has let me combine my passion for business with my passion for the arts. Every day, I get to work with inspirational, dynamic people who motivate me. 1/24 There’s been much talk of culture in the media these past few weeks as a result of the federal government’s recent budget cuts. But there’s also been much talk about the success garnered by Canadian productions. One need only think of the tremendous box office success enjoyed by Starbuck. It was announced this week that DreamWorks has acquired the remake rights and that Ken Scott would be the director. Then, of course, there’s Monsieur Lazhar, which made it all the way to the Oscars! The Canadian audiovisual industry is a vibrant, active industry that touches us every day through our television screens, at the movies, and increasingly on our computers and phones. It is an industry deserving of our attention, notably because of its contribution to the culture and economy of our country. -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

2017 New York

CANADA NOW BEST NEW FILMS FROM CANADA 2017 APRIL 6 – 9 AT THE IFC CENTER, NEW YORK From the recent numerous international successes of Canadian directors such as Xavier Dolan (Mommy, It’s Only the End of the World), Denis Villeneuve (Arrival, and the forthcoming Blade Runner sequel), Philippe Falardeau (The Bleeder, The Good Lie) and Jean-Marc Vallée (Dallas Buyers Club, Wild, Demolition), you might be thinking that there must be something special in that clean, cool drinking water north of the 49th parallel. As this year’s selection of impressive new Canadian films reveals, you would not be wrong. With works from new talents as well as from Canada’s accomplished veteran directors, this series will transport you from the Arctic Circle to western Asia, from downtown Montreal to small town Nova Scotia. And yes, there will be hockey. Get ready to travel across the daring and dramatic contemporary Canadian cinematic landscape. Have a look at what’s now and what’s next in those cinematic lights in the northern North American skies. Thursday, April 6, 7:00PM RUMBLE: THE INDIANS WHO ROCKED THE WORLD CANADA 2017 | 97 MINUTES DIRECTOR: CATHERINE BAINBRIDGE, CO-DIRECTOR: ALFONSO MAIORANA Artfully weaving North American musicology and the devastating historical experiences of Native Americans, Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked The World reveals the deep connections between Native American and African American peoples and their musical forms. A Sundance 2017 sensation, Bainbridge’s and co-director Maiorana’s documentary charts the rhythms and notes we now know as rock, blues, and jazz, and unveils their surprising origins in Native American culture. -

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

ZOOM- Press Kit.Docx

PRESENTS ZOOM PRODUCTION NOTES A film by Pedro Morelli Starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley Theatrical Release Date: September 2, 2016 Run Time: 96 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Official Website: www.zoomthefilm.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: @screenmediafilm Instagram: @screenmediafilms Theater List: http://screenmediafilms.net/productions/details/1782/Zoom Trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=M80fAF0IU3o Publicity Contact: Prodigy PR, 310-857-2020 Alex Klenert, [email protected] Rob Fleming, [email protected] Screen Media Films, Elevation Pictures, Paris Filmes,and WTFilms present a Rhombus Media and O2 Filmes production, directed by Pedro Morelli and starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar, Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley in the feature film ZOOM. ZOOM is a fast-paced, pop-art inspired, multi-plot contemporary comedy. The film consists of three seemingly separate but ultimately interlinked storylines about a comic book artist, a novelist, and a film director. Each character lives in a separate world but authors a story about the life of another. The comic book artist, Emma, works by day at an artificial love doll factory, and is hoping to undergo a secret cosmetic procedure. Emma’s comic tells the story of Edward, a cocky film director with a debilitating secret about his anatomy. The director, Edward, creates a film that features Michelle, an aspiring novelist who escapes to Brazil and abandons her former life as a model. Michelle, pens a novel that tells the tale of Emma, who works at an artificial love doll factory… And so it goes.. -

HELENE KLODAWSKY Helene Klodawsky Has Been Writing And

HELENE KLODAWSKY Helene Klodawsky has been writing and directing social, political and arts documentaries for 20 years. Her films have been screened and televised around the world, and have received more than 25 awards, including honours from the Chicago International Film Festival, the San Francisco International Film Festival, the Jerusalem International Film Festival, the Mannheim International Film Festival, Hot Docs, Les Rendez-vous du Cinema Quebecois and the Academy of Canadian Cinema. Painted Landscapes of the Times (1986), Motherland (1994), What If (1999) Undying Love (2002) No More Tears Sister (2005), and Family Motel (2007) are some of her credits. Her newest feature documentary Malls R Us will be released in 2009. She is a graduate of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. Helene Klodawsky is a member of Doc Organization, the Director’s Guild of Canada and the Writer’s Guild of Canada. Contact: [email protected] FILMOGRAPHY RESEARCHER, WRITER AND DIRECTOR PRIMAL LOVE (feature film script in development) Set in the early 1970s, PRIMAL LOVE follows the adventures of troubled teenager Naomi Grossman as she discovers Primal Scream, a book that promises a revolutionary cure for “Neurosis”. Scriptwriting Grant, SODEC 2008. MALLS R US (to be released in 2009) A critical look at the global phenomenon of the shopping mall, explored through the eyes of mall developers, architects, labour organizers, environmentalists, dead mall activists, and an international cast of shoppers. Filmed in Canada, US, Europe, India, Dubai -

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special Programs 215 345 6789

County Theater 79 PreviewsMARCH – MAY 2012 DAMSELS IN DISTRESS DAMSELS INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTY T HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. How can you support ADMISSION COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER General ..............................................................$9.75 Be a member. Members ...........................................................$5.00 Become a member of the nonprofit County Theater and Seniors (62+) show your support for good Students (w/ID) & Children (<18). ..................$7.25 films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a member- Matinees ship form or join on-line. Your financial support is tax-deductible. Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 Make a gift. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .......................................$7.25 Your additional gifts and support make us even better. Your Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ..........................$5.00 donations are fully tax-deductible. And you can even put your Affiliated Theaters Members* .............................$6.00 name on a bronze star in the sidewalk! You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. Contact our Business Office at (215) 348-1878 x117 or at The above ticket prices are subject to change. [email protected]. Be a sponsor. *Affiliated Theaters Members Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange The County Theater, the Ambler Theater, and the Bryn Mawr Film for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety Institute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your membership will of ways – on our movie screens, in our brochures, and on our allow you $6.00 admission at the other theaters. -

MY INTERNSHIP in CANADA (Guibord S’En Va-T-En Guerre)

MY INTERNSHIP IN CANADA (Guibord s’en va-t-en guerre) Press Kit A political satire by Philippe Falardeau with Patrick Huard Irdens Exantus Clémence Dufresne-Deslières and Suzanne Clément INTERNATIONAL SALES CANADIAN DISTRIBUTION PUBLICITY Sébastien Beffa Sébastien Létourneau Judith Dubeau Films Distribution Les Films Christal IXION Communications +33 1 53 10 33 99 Tél : +1 514 336 9696 +1 514 495 8176 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] My Internship in Canada synopsis Guibord is an independent Member of Parliament who represents Prescott-Makadewà- Rapides-aux Outardes, a vast county in Northern Quebec. As the entire country watches, Guibord unwillingly finds himself in the awkward position of holding the decisive vote to determine whether Canada will go to war. Accompanied by his wife, his daughter and an idealistic intern from Haiti named Souverain (Sovereign) Pascal, Guibord travels across his district in order to consult his constituents. While groups of lobbyists get involved in a debate that spins out of control, the MP will have to face his own conscience. My Internship in Canada (Guibord s’en va-t-en guerre) is a biting political satire in which politicians, citizens and lobbyists go head-to-head tearing democracy to shreds. My Internship in Canada | September 2015 1 My Internship in Canada cast Steve Guibord Patrick HUARD Suzanne Suzanne CLÉMENT Souverain (Sovereign) Pascal Irdens EXANTUS Lune Clémence DUFRESNE-DESLIÈRES Stéphanie Caron-Lavallée Sonia CORDEAU Prime Minister -

Magic Mike August 2012

MAGA MAGIC MIKE AUGUST 2012... ““UnnhheessiiittaattiiinngglllyyThheeReexxiiisstthheebbeessttcciiinneemaaIIIhhaavveeeevveerrkknnoownn…”” ((SSuunnddaayyTiiimeess2012)) ““ppoossssiiibblllyyBrriiittaaiiinn’’’ssmoossttbbeeaauuttiiiffuulllcciiinneemaa.........””((BBC)) AUGUST 2012 Issue 89 www.therexberkhamsted.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6pm Sun 4.30-5.30pm To advertise email [email protected] INTRODUCTION Gallery 4-5 BEST IN AUGUST August Evenings 11 Coming Soon 26 August Films at a glance 26 August Matinees 27 Rants and Pants 42-43 SEAT PRICES (+ REX DONATION £1.00) Circle £8.00+1 Concessions £6.50+1 At Table £10.00+1 Concessions £8.50+1 Royal Box (seats 6) £12.00+1 From infidelity in Caramel, Nadine takes her or for the Box £66.00+1 All matinees £5, £6.50, £10 (box) +1 women to war. Where Do We Go Now BOX OFFICE : 01442 877759 Mon to Sat 10.30 – 6.00 Mon 6 7.30. Egypt/France/Italy/Lebanon 2012 Sun 4.30 – 6.30 FILMS OF THE MONTH Disabled and flat access: through the gate on High Street (right of apartments) Some of the girls and boys you see at the Box Office and Bar: Dayna Archer Liam Parker Julia Childs Amberly Rose Ally Clifton Georgia Rose Nicola Darvell Sid Sagar Romy Davis Liam Stephenson Karina Gale Tina Thorpe Ollie Gower Beth Wallman Elizabeth Hannaway Jack Whiting Billie Hendry-Hughes Olivia Wilson Thanks to McConaughey's oily power, it's not Abigail Kellett Roz Wilson Amelia Kellett Keymea Yazdanian all sex, violence & chicken legs. Lydia Kellett Yalda Yazdanian Killer Joe Fri 3 7.30/Sat 4 7.00 USA 2012 Ushers: Amy, Amy P, Annabel, Ella, Ellie, Ellen W, Hannah, India, James, Kitty, Luke, Meg, Tyree Sally Rowbotham In charge Alun Rees Chief projectionist (Original) Jon Waugh 1st assistant projectionist Martin Coffill Part-time assistant projectionist Anna Shepherd Part-time assistant projectionist Jacquie Rose Chief Admin Oliver Hicks Best Boy Simon Messenger Writer Jack Whiting Writer "Like a whole series of The Wire in a single Jane Clucas & Lynn Hendry PR/Sales/FoH film..."?? Luckily it's French. -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

The Fifth Republic at Fifty

Franco-Maghrebi Crossings International Conference November 3-5, 2011 Winthrop-King Institute for Contemporary French and Francophone Studies Florida State University, Tallahassee Conference Director: Alec G. Hargreaves Administrative Coordinator: Racha Sattati Program All sessions take place in the Diffenbaugh Building on the FSU campus. Details are subject to change. THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 3 11:45AM, 12:30PM, 1:15PM – Complimentary Bus from Hotel Duval (pick-up at North Monroe entrance) to FSU Campus 12:00 noon-6:00 pm – Registration, 4th floor, Diffenbaugh 1:30 pm-3:00 pm – Panels 1A, 1B, 1C Panel 1A, Diffenbaugh 009 From Colonial Conquest to Decolonization Chair: Lindsey Scott (FSU) Alisha Valani (University of Toronto) - Entre brassage et homogénéité : colonisation, exil et folie au Maghreb Jennifer Fredette (SUNY Albany) and Richard Fogarty (SUNY Albany) - Forever apart: Enduring themes of “otherness” in French discourse on North African Muslims and Islam, 1914-1918 and 1989-2011 Doris Gray ( Florida State University) - Tunisia after the revolution: the end of post- colonialism? Panel 1B, Diffenbaugh 129 Memory I Chair: Robyn Cope (FSU) Janice Gross (Grinnell College) - Slimane Benaïssa: Performing the Tightrope of Franco-Algerian Memory Eveline Caduc (Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis) - « Un futur pour héritages déterritorialisés » Patricia Reynaud (School of Foreign Service-Qatar Georgetown University) - Fractures et cicatrices dans Bent Keltoum Panel 1C, Diffenbaugh 005 Women Writers Chair: Virginia Osborn (FSU) Oana Panaite