The Tradition Continues(Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Vocal of Frank Foster

1 The TENORSAX of FRANK BENJAMIN FOSTER Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Oct. 7, 2020 2 Born: Cincinnati, Ohio, Sept. 23, 1928 Died: Chesapeake, Virginia, July 26, 2011 Introduction: Oslo Jazz Circle always loved the Count Basie orchestra, no matter what time, and of course we became familiar with Frank Foster’s fine tenorsax playing! Early history: Learned to play saxes and clarinet while in high school. Went to Wilberforce University and left for Detroit in 1949. Played with Wardell Gray until he joined the army in 1951. After his discharge he got a job in Count Basie's orchestra July 1953 after recommendation by Ernie Wilkins. Stayed until 1964. 3 FRANK FOSTER SOLOGRAPHY COUNT BASIE AND HIS ORCHESTRA LA. Aug. 13, 1953 Paul Campbell, Wendell Cully, Reunald Jones, Joe Newman (tp), Johnny Mandel (btp), Henry Coker, Benny Powell (tb), Marshal Royal (cl, as), Ernie Wilkins (as, ts), Frank Wess (fl, ts), Frank Foster (ts), Charlie Fowlkes (bar), Count Basie (p), Freddie Green (g), Eddie Jones (b), Gus Johnson (dm). Three titles were recorded for Clef, two issued, one has FF: 1257-5 Blues Go Away Solo with orch 24 bars. (SM) Frank Foster’s first recorded solo appears when he just has joined the Count Basie organization, of which he should be such an important member for years to come. It is relaxed and highly competent. Hollywood, Aug. 15, 1953 Same personnel. NBC-TV "Hoagy Carmichael Show", three titles, no solo info. Hoagy Carmichael (vo). Pasadena, Sept. 16, 1953 Same personnel. Concert at the Civic Auditorium. Billy Eckstine (vo). -

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail. Cottontail stands as a fine example of Ellington’s “Blanton-Webster” years, where the band was at its peak in performance and popularity. The “Blanton-Webster” moniker refers to bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, who recorded Cottontail on May 4th, 1940 alongside Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard, Chauncey Haughton, and Harry Carney on saxophone; Cootie Williams, Wallace Jones, and Ray Nance on trumpet; Rex Stewart on cornet; Juan Tizol, Joe Nanton, and Lawrence Brown on trombone; Fred Guy on guitar, Duke on piano, and Sonny Greer on drums. John Hasse, author of The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, states that Cottontail “opened a window on the future, predicting elements to come in jazz.” Indeed, Jimmy Blanton’s driving quarter-note feel throughout the piece predicts a collective gravitation away from the traditional two feel amongst modern bassists. Webster’s solo on this record is so iconic that audiences would insist on note-for-note renditions of it in live performances. Even now, it stands as a testament to Webster’s mastery of expression, predicting techniques and patterns that John Coltrane would use decades later. Ellington also shows off his Harlem stride credentials in a quick solo before going into an orchestrated sax soli, one of the first of its kind. After a blaring shout chorus, the piece recalls the A section before Harry Carney caps everything off with the droning tonic. Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue. This piece is remarkable for two reasons: Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue exemplifies Duke’s classical influence, and his desire to write more grandiose pieces with more extended forms. -

Ready Rudy? Full Score

Jazz Lines Publications Presents ready rudy? Arranged by duke pearson transcribed and Prepared by Dylan Canterbury full score jlp-7333 Music by Duke Pearson Copyright © 1965 Gailancy Music International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2015 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. This Arrangement Has Been Published with the Authorization of the Estate of Duke Pearson. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA duke pearson series ready rudy? (1966) Background: Duke Pearson was an important pianist, composer, arranger and producer during the 1960s and 1970s. He was born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1932 and played trumpet as well as piano with many local groups. After attending Clark College, he toured with Tab Smith and Little Willie John before he moved to New York City in January of 1959. Donald Byrd heard him, and Byrd was the leader of Pearson’s first recording session. Soon Pearson was playing with the Benny Golson-Art Farmer Jazztet. Pearson became the musical director for Nancy Wilson, as well as continuing to tour and record with Donald Byrd. In 1963, Blue Note Records producer and musical director Ike Quebec passed away, and Pearson became Blue Note’s A&R director, as well as make his own albums. Grant Green, Stanley Turrentine, Johnny Coles, Blue Mitchell, Hank Mobley, Bobby Hutcherson, Lee Morgan and Lou Donaldson all benefited from his arranging and producing skills. Albums that Pearson recorded under his own name ranged in instrumentation from trios to quintets, sextets and octets to choral ensembles. -

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Seconded By~+--~· \ Gq '

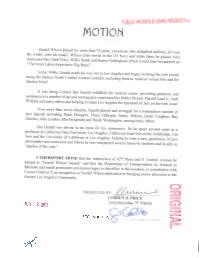

PUBUC WORKS &GANG REDUCTiO. -. MOTION Gerald Wilson played for more than 75 years, a musician who delighted millions, all over the world, with his music. Wilson later served in the US Navy and while there he played with musicians like Clark Terry, Willie Smith and Jimmy Nottingham which would later be reunited as "The Great Lakes Experience Big Band." In the 1940s, Gerald made his way out to Los Angeles and began working the club circuit along the famous South Central Avenue corridor, including famous musical venues like and the Dunbar Hotel. It was along Central that Gerald solidified his musical career, providing guidance and assistance to a number of up and coming jazz musicians like Bobby Bryant, Harold Land Jr., Jack Wilkins and many others and helping to make Los Angeles the epicenter of Jazz on the west coast. Over more than seven decades, Gerald played and arranged for a tremendous number of jazz legends including Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Nancy Wilson, Sarah Vaughan, Ray Charles, Julie London, Ella Fitzgerald and Dinah Washington, among many others. But Gerald was driven to do more for his community. So he spent several years as a professor at California State University Los Angeles, California State University Northridge, Cal Arts and the University of California at Los Angeles, helping to train a new generation of jazz aficionados and musicians and where he was recognized several times by students and faculty as "teacher ofthe year." I THEREFORE MOVE that the intersection of 42nd Place and S. Central Avenue be named as "Gerald Wilson Square" and that the Department of Transportation be directed to fabricate and install permanent ceremonial signs to this effect at this location, in consultation with Council District 9, in recognition of Gerald Wilson dedication to bringing music education to the Greater Los Angeles Community. -

Powell, His Trombone Student Bradley Cooper, Weeks

Interview with Benny Powell By Todd Bryant Weeks Present: Powell, his trombone student Bradley Cooper, Weeks TBW: Today is August the 6th, 2009, believe it or not, and I’m interviewing Mr. Benny Powell. We’re at his apartment in Manhattan, on 55th Street on the West Side of Manhattan. I feel honored to be here. Thanks very much for inviting me into your home. BP: Thank you. TBW: How long have you been here, in this location? BP: Over forty years. Or more, actually. This is such a nice location. I’ve lived in other places—I was in California for about ten years, but I’ve always kept this place because it’s so centrally located. Of course, when I was doing Broadway, it was great, because I can practically stumble from my house to Broadway, and a lot of times it came in handy when there were snow storms and things, when other musicians had to come in from Long Island or New Jersey, and I could be on call. It really worked very well for me in those days. TBW: You played Broadway for many years, is that right? BP: Yeah. TBW: Starting when? BP: I left Count Basie in 1963, and I started doing Broadway about 1964. TBW: At that time Broadway was not, nor is it now, particularly integrated. I think you and Joe Wilder were among the first to integrate Broadway. BP: It’s funny how it’s turned around. When I began in the early 1960s, there were very few black musicians on Broadway, then in about 1970, when I went to California, it was beginning to get more integrated. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

QUASIMODE: Ike QUEBEC

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ QUASIMODE: "Oneself-Likeness" Yusuke Hirado -p,el p; Kazuhiro Sunaga -b; Takashi Okutsu -d; Takahiro Matsuoka -perc; Mamoru Yonemura -ts; Mitshuharu Fukuyama -tp; Yoshio Iwamoto -ts; Tomoyoshi Nakamura -ss; Yoshiyuki Takuma -vib; recorded 2005 to 2006 in Japan 99555 DOWN IN THE VILLAGE 6.30 99556 GIANT BLACK SHADOW 5.39 99557 1000 DAY SPIRIT 7.02 99558 LUCKY LUCIANO 7.15 99559 IPE AMARELO 6.46 99560 SKELETON COAST 6.34 99561 FEELIN' GREEN 5.33 99562 ONESELF-LIKENESS 5.58 99563 GET THE FACT - OUTRO 1.48 ------------------------------------------ Ike QUEBEC: "The Complete Blue Note Forties Recordings (Mosaic 107)" Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded July 18, 1944 in New York 34147 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.35 Blue Note 6507 37805 BLUE HARLEM 4.33 Blue Note 37 37806 INDIANA 3.55 Blue Note 38 39479 SHE'S FUNNY THAT WAY 4.22 --- 39480 INDIANA 3.53 Blue Note 6507 39481 BLUE HARLEM 4.42 Blue Note 544 40053 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.36 Blue Note 37 Jonah Jones -tp; Tyree Glenn -tb; Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Oscar Pettiford -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded September 25, 1944 in New York 37810 IF I HAD YOU 3.21 Blue Note 510 37812 MAD ABOUT YOU 4.11 Blue Note 42 39482 HARD TACK 3.00 Blue Note 510 39483 --- 3.00 prev. unissued 39484 FACIN' THE FACE 3.48 --- 39485 --- 4.08 Blue Note 42 Ike Quebec -ts; Napoleon Allen -g; Dave Rivera -p; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. -

![Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Thad Jones & Mel Lewis: Live at the Village Vanguard] Down Beat 35:8 (April 18, 1968)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5438/morgenstern-dan-record-review-thad-jones-mel-lewis-live-at-the-village-vanguard-down-beat-35-8-april-18-1968-225438.webp)

Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Thad Jones & Mel Lewis: Live at the Village Vanguard] Down Beat 35:8 (April 18, 1968)

Records are reviewed by Don DeMicheal, Gilbert M. Erskine, Kenny Dorha m, Barbara Gardner, Bill Mathieu, Marian McPartland, Dan Mor 11e nslar Bill Quinn, Harvey Pekar, William Russo, Harvey Siders, Pete Welding, John S. Wilson, and Michael Zwerin. Reviews are signed by !lie Wr't n, I ers Ratings are : * * * * * excellent, * * * * very good, * * * good, * * fair, * poor . ' When two catalog numbers are listed, the first is mono, and the second is stereo . times (especially on Yellow Days) · his Thad Jones-Mel Lewis •- •- -. ... touch is uncannily close to the master 's. LIVE AT THE Vl.LLAGB VANGUA.ll." Solid S1A1e SS l80l6: L/lflc Pi:<lo ll; ,1 "/l'v..,. BIG BANDS Two ringers were brought in to beef up l'reodom; Barba l'eo/i11'; Do11'1 Git Sn1ty• tltl•, /0111 Tree; Samba Co11 Gde/m. ' "' 1I. Duke Ellington the trumpet section, currently the ban.d's weakest link. Everybody was on best be Personnel: Jone1, flu·cgelhoro; Snooky y 0 SOUL CALL-Verve V/V6·870l: La Pim Bell• Jimmy No1tingb3m, Marvin Stamm, Rkfiard ~•• Af.-i&11l11r;IVett litdia11 Pa11caltt; Soul C111/;Slti11 Jiavior, it seems-the band sounds tight Iiams, Bill Berry. trumpets; Bob Brool<o, II, Du/I; Jan, Will, Sm11. and together at all times. The superb ·re Garnett Bl'owo, Tom Mclmo,h, Cliff fi~a~yer, Personnel: Cnt Anderson, Herbie Jones, Cootie irombones; Jerome Richnrdson, Jerry Dad !>tr, \Villla 'ms. M,rccer I!llingron. uumpors; Buster cord ing brings out the foll flavor of the Joe Parcell, '.Eddie Daniels, -Pepper Adams r~t• lloiaod Hannn piano; Sam Herm an, • IM • Cooper, Lawrence Brown, Chuck Connors , rrom• magnificent Ellington sound; the reeds, in 1 bonci.: Russell Procope. -

Thad Jones Discography Copy

Thad Jones Discography Compiled by David Demsey 2012-15 Recordings released during Thad Jones’ lifetime, as performer, bandleader, composer/arranger; subsequent CD releases are listed where applicable. Each entry lists Thad Jones compositions/arrangements contained on that recording. Album titles preceded by (•) are contained in the Thad Jones Archive collection. I. As a Leader or Co-Leader Big Band Leader or Co-Leader (chronological): • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Live at the Vanguard (rec. 1/7 [sic], 3/21/66) [live recording donated by George Klabin] Contains: All My Yesterdays (2 versions), Backbone, Big Dipper (2 versions), Mean What You Say, Morning Reverend, Little Pixie, Willow Weep for Me (Brookmeyer), Once Around, Polka Dots and Moonbeams (small group), Low Down, Lover Man, Don’t Ever Leave Me, A-That’s Freedom • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, On Tour (rec. varsious dates and locations in Europe) Discs 1-7, 10-11 [see Special Recordings section below] On iTunes. • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, In the Netherlands (rec. 1974) [unreleased live recording donated by John Mosca] • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Presenting the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra (rec. 5/4-5-6/66) Solid State UAL18003 Contains: Balanced Scales = Justice, Don’t Ever Leave Me, Mean What You Say, Once Around, Three and One • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Opening Night (rec. 1[sic]/7/66, incorrect date; released 1990s) Alan Grant / BMG Ct. # 74321519392 Contains: Big Dipper, Polka Dots and Moonbeams (small group), Once Around, All My Yesterdays, Morning Reverend, Low Down, Lover Man, Mean What You Say, Don’t Ever Leave Me, Willow Weep for Me (arr. -

Jazzletter Jujy 1936, VOI

Jazzletter Jujy 1936, VOI. 5 NO. 7 \ how much jazz had infused his playing. The miscegenation of Are You Reading jazz and hillbilly has longgone on in-Nashville. and some ofthe best of its players are at ease in both idioms. Someone Else’s Copy? Lenny Breau came up through country-and-western music. Each issue of The Underground Grammarian contains the his parents beingprofessionals in the field. and it was'Nashville above question. lt’s discouraging. in the struggle to keep a small that made him welcome. He is. like Garland,‘Carllile and Reed, publication alive. to hear someone say something like, “-1 just the result ofthejazz-country fusion, exceptythat Breau took it a love it. A friend sends me his copies when he’s through with step further and brought into his work the full range ofclassical them.” . A guitar technique. Chet Atkins was the first a&r man to givehim ' In publications supported by advertising. salesmen boast to his head, letting him record for RCAia milestone album in potential advertisers about how many people read each copy. which he showed 0-ff his startling. .for the time, jazz-classical and to the advertiser seeking exposure of his message. those ‘technique, Gene Bertoncini, who is ‘probably the best living figures have weight. He is less interested in how manyypeople exponent of jazz on the five-finger classical guitar. admires buy a periodical than in how many see it. An important Breau; but then you’ll search far to find a guitarist who doesn’t. phenomenon in periodical publishing is what is known as Lenny was a heroin addict. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman,