Livestock Grazing and Its Effects on Ecosystem Structure, Processes, and Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livestock and Landscapes

SUSTAINABILITY PATHWAYS LIVESTOCK AND LANDSCAPES SHARE OF LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION IN GLOBAL LAND SURFACE DID YOU KNOW? Agricultural land used for ENVIRONMENT Twenty-six percent of the Planet’s ice-free land is used for livestock grazing LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION and 33 percent of croplands are used for livestock feed production. Livestock contribute to seven percent of the total greenhouse gas emissions through enteric fermentation and manure. In developed countries, 90 percent of cattle Agricutural land used for belong to six breed and 20 percent of livestock breeds are at risk of extinction. OTHER AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION SOCIAL One billion poor people, mostly pastoralists in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, depend on livestock for food and livelihoods. Globally, livestock provides 25 percent of protein intake and 15 percent of dietary energy. ECONOMY Livestock contributes up to 40 percent of agricultural gross domestic product across a significant portion of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa but receives just three percent of global agricultural development funding. GOVERNANCE With rising incomes in the developing world, demand for animal products will continue to surge; 74 percent for meat, 58 percent for dairy products and 500 percent for eggs. Meeting increasing demand is a major sustainability challenge. LIVESTOCK AND LANDSCAPES SUSTAINABILITY PATHWAYS WHY DOES LIVESTOCK MATTER FOR SUSTAINABILITY? £ The livestock sector is one of the key drivers of land-use change. Each year, 13 £ As livestock density increases and is in closer confines with wildlife and humans, billion hectares of forest area are lost due to land conversion for agricultural uses there is a growing risk of disease that threatens every single one of us: 66 percent of as pastures or cropland, for both food and livestock feed crop production. -

2010 Schedule DI

Schedule Wisconsin Dairy and Livestock Farm Investment Credit DI File with Wisconsin Form 1, 1NPR, 2, 3, 4, 4T, 5, or 5S Name Identifying Number 2010 Wisconsin Department of Revenue 1 Fill in the amount paid in 2010 for the following items if used exclusively for dairy or livestock farm modernization or expansion: a Freestall barns . 1a b Fences . 1b c Watering facilities . 1c d Feed storage and handling equipment . 1d e Milking parlors . 1e f Robotic equipment . 1f g Scales . 1g h Milk storage and cooling facilities . 1h i Bulk tanks . 1i j Manure pumping and storage facilities . 1j k Digesters . 1k l Equipment used to produce energy . 1l m Birthing and rearing structures . 1m n Feedlot structures . 1n o Fish hatchery buildings, fish processing buildings, and fish rearing ponds . 1o p Other (list) 1p 2 Add lines 1a through 1p . 2 3 Multiply line 2 by 10% (0.10) . 3 4 Fill in 2010 dairy and livestock farm investment credit passed through from other entities . 4 5 Add lines 3 and 4 . 5 6 a Maximum credit . 6a $75,000 b Enter credit computed for 2004 to 2009 (from 2009 Schedule DI, line 6b plus line 7) . 6b c Subtract line 6b from line 6a . 6c 7 Fill in the smaller of line 5 or line 6c. See instructions . 7 7a Fiduciaries - Enter amount of credit from line 7 allocated to beneficiaries . 7a 7b Fiduciaries - Subtract line 7a from line 7 . 7b 8 Carryover of unused 2004 to 2009 dairy and livestock farm investment credit . 8 9 Add lines 7 and 8. -

Conservation Grazing.Pdf

MINNESOTA WETLAND RESTORATION GUIDE CONSERVATION GRAZING TECHNICAL GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Document No.: WRG 6A-5 Publication Date: 1/30/2014 Table of Contents Introduction Application Other Considerations Costs Additional References INTRODUCTION Grazing by bison, elk and deer was historically a natural occurrence in grassland and shrubland plant communities in Minnesota. This grazing tended to be nomadic in nature and its intensity depended on the type of grazers, herd sizes, climate conditions, fire frequency, and the composition and structure of individual plant communities. Today conservation grazing is conducted by a variety of species including cattle, bison, horses, sheep, and goats to target specific invasive plants, or to replicate the grassland plant community structure and diversity that historically resulted from grazing. When grazing is conducted to control invasive species the intensity and duration of grazing is carefully monitored to ensure that target species are managed effectively, and that the integrity of the plant community is maintained. Most conservation grazing involves a short pulse of grazing followed by a long rest. Grazing can have benefits as well as negative impacts, so it is important to involve experienced professionals. Detailed grazing plans are an important component in the planning and implementation of prescribed grazing. Equipment that may be needed for grazing includes watering systems, electric, or barb”ed” wire fences around rotational grazing areas, moveable fencing to concentrate grazing and to ensure that areas are not overgrazed, and in some cases salt licks to concentrate animals (Tu et al. 2001). The following is a list of species commonly used for conservation grazing and their general characteristics. -

Management of Grazing Animals for Environmental Quality

Management of grazing animals for environmental quality Etienne M. in Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products Zaragoza : CIHEAM Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67 2005 pages 225-235 Article available on line / Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=6600046 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ To cite this article / Pour citer cet article -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ Etienne M. Management of grazing animals for environmental quality. In : Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products . Zaragoza : CIHEAM, 2005. p. 225-235 (Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://www.ciheam.org/ -

Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project Final Report

UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project ATLAS ID GEF-00013971 TRAC-00013970 (formerly NEP/99/G35 and NEP/99/021) Final Report of the Terminal Evaluation Mission September 2006 Phillip Edwards (Team Leader) Rajendra Suwal Neeta Thapa ACRONYMS AND TERMS Exchange rate at the time of the TPE was US$1 to NR 71 (Nepali Rupees) ACA Anapurna Conservation Area ACAP Anapurna Conservation Area Project AHF American Himalayan Foundation APPA Appreciative Participatory Planning and Action BCP Biodiversity Conservation Plan CAMC Conservation Area Management Committee CAMOP Conservation Area Management Operation Plan CAMP Conservation Area Management Plan CAMR Conservation Area Management Regulation CBBMS Community Based Biodiversity Monitoring System CBO Community Based Organization CITES Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species CPM Co-Project Manager CRAC Community Resource Action Area Committee CRAJSC Community Resources Action Joint Sub-Committee CTF Community Trust Fund DAG Disadvantage Group DDC District Development Committee DNPWC Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation EIA Environment Impact Assessment FIT Free Independent Tourist/Trekker GEF Global Environment Facility GIS Geographic Information System GON Government of Nepal Ha. Hectares HMG His Majesty’s Government HQ Head Quarters HRD Human Resource Development ICDP Integrated Conservation Development Program ICIMOD International Center for Integrated Mountain Development IEA Initial Environmental Assessment IGA Income -

HOW DOES a LIVESTOCK AUCTION WORK? Paperwork That Goes to the Processor

HOW DOES A LIVESTOCK AUCTION WORK? paperwork that goes to the processor. You need to contact the processor to process and package according to your needs When you arrive at the auction, you need to stop at the Sale Office located in the front • Standard processing only for chickens, turkeys and ducks. corner of the auction barn. Here you will register for a bidder number which will identify • Donate the processed meat the the Second Harvest Food Bank. You will also you to the auctioneer when you buy. Use the first line of the bidder registration card for the need to pay for the processing costs since they do not have the funds to pay for name you want to be announced as the buyer. Due to computer program limitations, space the costs. is limited. • Sell the animal back to the Livestock Sale Committee at the buyback prices posted on the day of the auction. Your cost is the difference between the amount You will also receive a copy of the Sale Catalog, which list the animals in the order to be that you bid, less the buyback. This does not apply to Grand or Reserve Champion sold, along with a lot of information for buyers. NOTE: All Grand and Reserve Champion Market Beef, Hogs, Lambs and Goats. market beef, hogs, lambs and goats must be slaughtered after the auction – BUYBACK IS • Donate the animal back to the exhibitor – except for any grand or reserve NOT AN OPTION FOR THESE ANIMALS. champion market beef, hogs, lambs and goats. As the auction starts, the auctioneer will announce what is being sold, either by the pound • Take the animal home - – except for any grand or reserve champion market beef, or by the lot. -

Livestock-Keeping and Animal Husbandry in Refugee and Returnee Situations

LIVESTOCK-KEEPING AND ANIMAL HUSBANDRY IN REFUGEE AND RETURNEE SITUATIONS A PRACTICAL HANDBOOK FOR IMPROVED MANAGEMENT Acknowledgements Our genuine appreciation to The World Conservation Union (IUCN) in Gland, Geneva for their technical expertise and invaluable revision of the Handbook on Livestock Keeping and Animal Husbandry in Refugee and Returnee Situations. We extend our thanks to the UNHCR Field Environmental Coordinators and Focal Points and other colleagues for their very useful comments and additional inputs. Illustrations prepared by Dorothy Migadee, Nairobi, Kenya Background & cover images: ©Irene R Lengui/L’IV Com Sàrl Design and layout by L’IV Com Sàrl, Morges, Switzerland Printed by: SroKundig, Geneva, Switzerland Produced by the Environment, Technical Support Section, UNHCR Geneva and IUCN, August 2005 2 Refugee Operations and Environmental Management Table of Contents Glossary and Acronyms 5 Executive Summary 7 1. Livestock Management in Refugee-Related Operations 9 1.1 Introduction 9 1.2 Livestock-Keeping in Refugee-Related Operations 10 2. Purpose and Use of this Handbook 14 2.1 Introduction 14 2.2 Using this Handbook 14 3. Livestock Management: Some Basic Considerations 16 3.1 Introduction 16 3.2 Traditional and Legal Rules and Regulations 16 3.3 Livestock to Suit the Conditions 17 3.4 Impacts Commonly Associated with Livestock-Keeping 18 3.4.1 Some Positive Impacts of Livestock-Keeping 18 3.4.2 Some Negative Impacts of Livestock in Refugee Situations 19 3.4.2.1 Impacts on Natural Resources 19 3.4.2.2 Social Conflicts 20 3.4.2.3 Impacts on Public Health 21 3.5 Disease Avoidance and Control 22 3.5.1 Common Livestock Diseases 22 3.5.2 Maintaining Animal Health 25 3.5.3 Avoiding Negative Impacts on Public Health 28 3.6 Housing 29 3.7 Carrying Capacity 30 3.8 Resource Competition 32 4. -

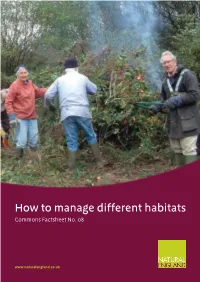

How to Manage Different Habitats Commons Factsheet No

How to manage different habitats Commons Factsheet No. 08 www.naturalengland.co.uk How to manage different habitats Many commons and greens are beautiful places, rich in wildlife. Because commons have a long history of being used by people, the habitats they support are relatively natural but have been shaped by human activities over the millennia (e.g. unimproved grassland, heathland, woodlands). If they are to retain their wildlife and scenery the traditional uses must either be continued, or replicated some other way (see FS3 Why does our common need to be looked after?). This factsheet summarises the characteristic features of each habitat type, together with conservation aims and management techniques for habitats frequently found on commons. Different techniques Before deciding on particular management techniques, you will want to consider their The management of habitats can vary from potential impact on the species present, simple to complex. It can often be carried the landscape, the environment, features out by volunteers with hand tools or may of archaeological and historical interest, need people with specialised training and and public access and safety (see FS5 Is our equipment. Here, the main methods you common more special than we think?, FS4 Who might use are outlined and sources of further has an interest in the common? and FS8 What information signposted. Herbicide treatments future for our commons?). Remember to plan are not discussed, as these are best used only aftercare and monitoring (see FS17 Are we if there are no other realistic options, and getting it right?). you will want specialist advice and possibly contractors to carry out the work. -

Industrial Agriculture, Livestock Farming and Climate Change

Industrial Agriculture, Livestock Farming and Climate Change Global Social, Cultural, Ecological, and Ethical Impacts of an Unsustainable Industry Prepared by Brighter Green and the Global Forest Coalition (GFC) with inputs from Biofuelwatch Photo: Brighter Green 1. Modern Livestock Production: Factory Farming and Climate Change For many, the image of a farmer tending his or her crops and cattle, with a backdrop of rolling fields and a weathered but sturdy barn in the distance, is still what comes to mind when considering a question that is not asked nearly as often as it should be: Where does our food come from? However, this picture can no longer be relied upon to depict the modern, industrial food system, which has already dominated food production in the Global North, and is expanding in the Global South as well. Due to the corporate take-over of food production, the small farmer running a family farm is rapidly giving way to the large-scale, factory farm model. This is particularly prevalent in the livestock industry, where thousands, sometimes millions, of animals are raised in inhumane, unsanitary conditions. These operations, along with the resources needed to grow the grain and oil meals (principally soybeans and 1 corn) to feed these animals place intense pressure on the environment. This is affecting some of the world’s most vulnerable ecosystems and human communities. The burdens created by the spread of industrialized animal agriculture are wide and varied—crossing ecological, social, and ethical spheres. These are compounded by a lack of public awareness and policy makers’ resistance to seek sustainable solutions, particularly given the influence of the global corporations that are steadily exerting greater control over the world’s food systems and what ends up on people’s plates. -

MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 Habitats * Semi-Natural Dry Grasslands (Festuco- Brometalia) 6210

Technical Report 2008 12/24 MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 habitats * Semi-natural dry grasslands (Festuco- Brometalia) 6210 The European Commission (DG ENV B2) commissioned the Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 6210 Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates ( Festuco-Brometalia ) (*important orchid sites) This document was prepared in March 2008 by Barbara Calaciura and Oliviero Spinelli, Comunità Ambiente Comments, data or general information were generously provided by: Bruna Comino, ERSAF Regione Lombardia, Italy Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Mats O.G. Eriksson, MK Natur- och Miljökonsult HB, Sweden Monika Janisova, Institute of Botany of Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovak Republic) Stefano Armiraglio, Museo di Scienze Naturali di Brescia, Italy Stefano Picchi, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Guy Beaufoy, EFNCP - European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, UK Gwyn Jones, EFNCP - European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, UK Coordination: Concha Olmeda, ATECMA & Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente 2008 European Communities ISBN 978-92-79-08326-6 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Calaciura B & Spinelli O. 2008. Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 6210 Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates ( Festuco-Brometalia ) (*important orchid sites). European Commission This document, which has been prepared in the framework of a service contract (7030302/2006/453813/MAR/B2 "Natura 2000 preparatory actions: Management Models for Natura -

Bryn Tip Local Nature Reserve

BRYN TIP LOCAL NATURE RESERVE The village of Bryn is lucky enough to have its own Nature Reserve! The Reserve is popular with the residents of Bryn and visitors from further afield who come to walk their dogs, ride horses on the bridle way or take a gentle stroll whilst enjoying the wildlife and views of the surrounding countryside. The site has been used all year round and is also the starting point for the Bryn Heritage walk. This Reserve is home to hundreds of species of wildlife including flowers, fungi, invertebrates, birds, reptiles and mammals. The site was declared a Local Nature Reserve in order to protect the wildlife and preserve the landscape for people to enjoy long into the future. CONSERVATION GRAZING Over the last few years, the Countryside & Wildlife Team of the Local Authority have been working with contractors, and occasionally volunteers, to reduce the amount of invasive scrub on the site. This initial intensive management has allowed the grasses and flowering plants to flourish in those areas. However, unless the scrub is regularly managed it will become dense and eventually take over the grassland, making the site a lot less attractive to walk through. Similarly, the grassland is becoming rank and tussock and unless it is managed sensitively, much of the special wildlife will be lost. Using contractors and staff is not a sustainable long term approach for managing the Nature Reserve, even less so with the current and proposed budget cuts that the Local Authority is faced with. Conservation grazing is a more traditional, sustainable and less labour-intensive way of getting the grassland into good condition and keeping the scrub under control. -

Intensive Livestock Farming: Global Trends, Increased Environmental Concerns, and Ethical Solutions

J Agric Environ Ethics (2009) 22:153–167 DOI 10.1007/s10806-008-9136-3 Intensive Livestock Farming: Global Trends, Increased Environmental Concerns, and Ethical Solutions Ramona Cristina Ilea Accepted: 14 November 2008 / Published online: 11 December 2008 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008 Abstract By 2050, global livestock production is expected to double—growing faster than any other agricultural sub-sector—with most of this increase taking place in the developing world. As the United Nation’s four-hundred-page report, Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options, documents, livestock production is now one of three most significant contributors to environmental problems, leading to increased greenhouse gas emissions, land degradation, water pollution, and increased health prob- lems. The paper draws on the UN report as well as a flurry of other recently published studies in order to demonstrate the effect of intensive livestock production on global warming and on people’s health. The paper’s goal is to outline the problems caused by intensive livestock farming and analyze a number of possible solutions, including legis- lative changes and stricter regulations, community mobilizing, and consumers choosing to decrease their demand for animal products. Keywords Agriculture Á Animals Á Environment Á Ethics Á Farming Á Livestock Á Meat Global Trends and Overview Approximately 56 billion land animals are raised and killed worldwide every year for human consumption (FAO, n.d.).1 By 2050, global farm animal production is expected to double—growing faster than any other agricultural sub-sector—with most of those increases taking place in the developing world (FAO 2006b, p.