Compartment Syndrome and Volkmann Ischemic Contracture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatomy of the Forearm Musculoskeletal Block - Lecture 9

Anatomy of the forearm Musculoskeletal Block - Lecture 9 Objective: ✓ List the names of the Flexors and Extensor Group of Forearm (superficial & deep muscles). ✓ Identify the common flexor origin of flexor muscles and their innervation & movements. ✓ Identify supination & pronation and list the muscles produced these 2 movements. ✓ Describe the effect of injury of the muscle or its origin ✓ Identify the common extensor origin of extensor muscles and their innervation & movements. Color index: Important In male’s slides only In female’s slides only Extra information, explanation Editing file Contact us: [email protected] Forearm 1- The forearm extends from the elbow to wrist. 2- It posses two bones radius laterally and ulna medially. 3- The two bones are connected to each other by interosseous membrane. 4- This membrane allows movement of pronation and supination while the two bones are connected together. 5- also it gives origin to the deep muscles. Fascial compartment of the forearm 1- The forearm is enclosed in a sheath of deep fascia, which is attached to the posterior border of ulna (it encircle the forearm completely (Without touching the radius) and return again to the posterior border of the ulna) 2- This fascial sheath together with the interosseous membrane and fibrous intermuscular septa divides the forearm into (anterior and posterior) compartments each having its own muscles, nerves and blood supply. (The radius and ulna are connected by 3 structures: the interosseous membrane, superior radioulnar joint and inferior radioulnar joint). Anterior compartment - FLEXOR GROUP 1- 8 muscles.. 2- They act on the elbow and wrist joints and the fingers. -

Treatment of Established Volkmann's Contracture*

~hop. Acta Treatment of Established Volkmann’sContracture* BY KENYA TSUGE, M.D.’J’, HIROSHIMA, JAPAN ldon, From the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Hiroshima Universi~.’ 1-76, School of Medicine, Hiroshima 38. The disease first described by Volkmann in 1881 is the extent of the disease: mild, moderate, and severe. In generally considered to result from spasm of the main ar- the mild type, also called the localized type, there was de- ~ts of teries of the forearm, and their branches as a consequence generation of part of the flexor digitorum profundus mus- Acta of trauma to the elbow or forearm. The severe and pro- cle, causing contractures in only two or three fingers. longed but incomplete interruption of arterial blood sup- There were hardly any neurological signs, and when pres- ~. (in ply, together with venostasis, produces acute ischemic ent they were minimum. In the moderate type, the muscle z and necrosis of the flexor muscles. The most marked ischemia degeneration involved all or nearly all of the flexor digito- occurs in the deeply situated muscles such as the flexor rum profundus and flexor pollicis longus, with partial pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus, but severe degeneration of the superficial muscles as well. The neu- ischemia is evident in the pronator teres and flexor rological signs were invariably present and generally -484, digitorum superficialis muscles, and comparatively mild the median nerve was more severely affected than the :rtag, ischemia occurs in the superficially located muscles such ulnar nerve. In the severe type, there was degeneration as the wrist flexors. The muscle degeneration which fol- of all the flexor muscles with necrosis in the center ). -

Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis And

yst ar S em ul : C c u s r u r e M n t & R Orthopedic & Muscular System: c e Aydin, et al., Orthopedic Muscul Syst 2014, 3:2 i s d e e a p ISSN: 2161-0533r o c DOI: 10.4172/2161-0533-3-1000159 h h t r O Current Research Review Article Open Access Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment Nuri Aydin*, Okan Tok and Bariş Görgün Istanbul University Cerrahpaşa, School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey *Corresponding author: Nuri Aydin, Istanbul University Cerrahpaşa, School of Medicine, Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Istanbul, Turkey, Tel: +905325986232; E- mail: [email protected] Rec Date: Jan 25, 2014, Acc Date: Mar 22, 2014, Pub Date: Mar 28, 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Aydin N, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The term rotator cuff tear arthropathy is a broad spectrum pathology but it involves common characteristic features as rotator cuff tear, leading to glenohumeral joint arthritis and superior migration of the humeral head. Although there are several factors described causing rotator cuff tear arthropathy, the exact mechanism is still unknown because the rotator cuff tear arthropathy develops in only a group of patients with chronic rotator cuff tear. The aim of this article is to review pathophysiology of rotator cuff tear arthropathy, to explain the diagnostic features and to discuss the management of the disease. Keywords: Arthropathy; Glenohumeral joint; Articular fluid Rotator cuff tear not only plays a role at the beginning of the disease, but also a developed rotator cuff tear is a result of the inflammatory Introduction process. -

Case Report Forearm Compartment Syndrome Following Thrombolytic Therapy for Massive Pulmonary Embolism: a Case Report and Review of Literature

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Orthopedics Volume 2011, Article ID 678525, 4 pages doi:10.1155/2011/678525 Case Report Forearm Compartment Syndrome following Thrombolytic Therapy for Massive Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Report and Review of Literature Ravi Badge and Mukesh Hemmady Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics Surgery, Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Trust, Wigan WN1 2NN, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Ravi Badge, [email protected] Received 2 November 2011; Accepted 6 December 2011 Academic Editor: M. K. Lyons Copyright © 2011 R. Badge and M. Hemmady. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Use of thrombolytic therapy in pulmonary embolism is restricted in cases of massive embolism. It achieves faster lysis of the thrombus than the conventional heparin therapy thus reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with PE. The compartment syndrome is a well-documented, potentially lethal complication of thrombolytic therapy and known to occur in the limbs involved for vascular lines or venepunctures. The compartment syndrome in a conscious and well-oriented patient is mainly diagnosed on clinical ground with its classical signs and symptoms like disproportionate pain, tense swollen limb and pain on passive stretch. However these findings may not be appropriately assessed in an unconscious patient and therefore the clinicians should have high index of suspicion in a patient with an acutely swollen tense limb. In such scenarios a prompt orthopaedic opinion should be considered. In this report, we present a case of acute compartment syndrome of the right forearm in a 78 years old male patient following repeated attempts to secure an arterial line for initiating the thrombolytic therapy for the management of massive pulmonary embolism. -

Methodical Complex on Gross Anatomy for Ii Course

MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION OF UZBEKISTAN BUKHARA STATE MEDICAL INSTITUTE NAMED AFTER ABU ALI IBN SINO DEPARTMENT OF ANATOMY "APPROVED" by Vice-Rector for Academic and educational work, Associate prof. G.J.Jarilkasinova ________________________________ "_____" ________________ 2020 Area of knowledge: 500000 - Health and social care Education field: 510000 - Healthcare Educational direction: 5510100 - Medical business 5111000 - Professional education (5510100 - Medicine business) 5510200 - Pediatric Medicine 5510300 - Medico-prophylactic business 5510400 – Dentistry (by directions) 5510900 – Medico-biological business EDUCATIONAL - METHODICAL COMPLEX ON GROSS ANATOMY FOR II COURSE Bukhara 2020 The scientific program was approved by the Resolution of the Coordination Council No. ___ of August ___, 2020 on the activities of educational and methodological associations in the areas of higher and secondary special and vocational education. The teaching and methodical complex was developed by order of the Ministry of Higher and Secondary Special Education of the Republic of Uzbekistan dated March 1, 2017 No. 107. Compilers: Radjabov A.B. - Head of the Department of Anatomy, Associate Professor Khasanova D.A. - Assistant of the Department of Anatomy, PhD Bobomurodov N.L. - Associate Professor of the Department of Anatomy Reviewers: Davronov R.D. - Head of the Department Histology and Medical biology, Associate Professor Djuraeva G.B. - Head of the Department of the Department of Pathological Anatomy and Judicial Medicine, Associate Professor The working educational program for anatomy is compiled on the basis of working educational curriculum and educational program for the areas of 5510100 - Medical business. This is discussed and approved at the department Protocol № ______ of "____" _______________2020 Head of the chair, associate professor: Radjabov A.B. -

Orthopedic Trauma Postoperative Care and Rehab

Orthopedic Trauma Postoperative Care and Rehab Serge Charles Kaska, MD Name that Beach 100$ Still 100$ 75$ 50$ 1$ Omaha • June 6th 1941 • !st Infantry Division • 2000 KIA LIFE OR LIMB THREAT 1. Compartment Syndrome 2. Fat Emboli Syndrome 3. Pulmonary Embolism 4. Shock Compartment syndrome case A 16 year old male was retrieving a tire from his truck bed on the side of the highway in the pouring rain when a car careens off of the road and sandwiches the patients legs between the bumpers at freeway speed. Acute compartment syndrome Compartment syndrome DEFINED Definition: Elevated tissue pressure within a closed fascial space • Pathogenesis – Too much in-flow: results in edema or hemorrhage – Decreased outflow: results in venous obstruction caused by tight dressing and/or cast. • Reduces tissue perfusion • Results in cell death Compartment syndrome tissue survival • Muscle – 3-4 hours: reversible changes – 6 hours: variable damage – 8 hours: irreversible changes • Nerve – 2 hours: looses nerve conduction – 4 hours: neuropraxia – 8 hours: irreversible changes Physical exam 1. Pain 2. Pain 3. Pain Physical exam • Inspection – Swelling, skin is tight and shiny • Motion – Active motion will be refused or unable. Must see dorsiflexion • Palpation – Severe pain with palpation • Alarming pain with passive stretch Physical exam • Dorsiflexion Physical Exam • Palpation – Severe pain with palpation • Alarming pain with passive stretch Physical exam • Evaluations from nurses, therapists, and orthotech’s are CRITICAL • If you call a doctor and say that -

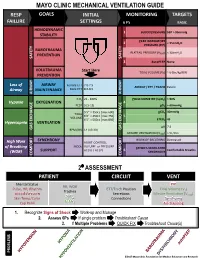

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Acute Compartment Syndrome Complicating Deep Venous Thrombosis

SMGr up Case Report SM Journal of Acute Compartment Syndrome Case Reports Complicating Deep Venous Thrombosis Senthil Dhayalan1*, David Jardine1*, Tony Goh2 and Nicholas Lash3 1Senior registrar and General Physician, Dept of General Medicine, NZ 2Consultant Radiologist, Dept of Radiology, NZ 3Orthopaediac Surgeon, Dept of Orthopaedics, NZ A 40-yr old, heavily-built man initially presented to his general practitioner 2 days before Article Information admission with recent onset of pain and swelling in his left calf. A duplex ultrasound scan Received date: Nov 21, 2018 demonstrated a popliteal and lower leg deep vein thrombosis [DVT], extending 15 cm above the Accepted date: Nov 26, 2018 knee into the femoral vein. He was started appropriately on enoxaparin 130 mg bd. Despite the Published date: Nov 27, 2018 treatment, the pain got worse, particularly when standing, and he was admitted for symptom control. Five weeks earlier he had undergone anterior cruciate ligament repair of the left knee, *Corresponding author [without heparin prophylaxis] and made a satisfactory recovery (Figure 1). Jardine D, General Medicine On examination he was mildly distressed with a low-normal blood pressure [110/70 mmHg] Department, Christchurch hospital, and a persistent low-grade fever [temperature ranged from 37.0-37.8 oC]. The left leg was moderately Private Bag 4710, Christchurch 8140, diffusely swollen, slightly warm and darker in colour [figure]. The pain was localised to the posterior New Zealand, compartments and was exacerbated by dorsi-flexing the ankle and squeezing the gastrocnemius. Email: [email protected] There were no signs of joint effusion, thrombophlebitis, lymphadenopathy or cellulitis. -

Table of Contents 1

GENERAL THORACIC SURGERY DATABASE v.2.3 TRAINING MANUAL August 2017 Table of Contents 1. Demographics ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Follow Up ........................................................................................................................................................................ 9 3. Admission ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 4. Pre-Operative Evaluation ............................................................................................................................................. 14 5. Diagnosis (Category of Disease) ................................................................................................................................... 48 6. Procedure ..................................................................................................................................................................... 70 7. Post-Operative Events ................................................................................................................................................ 111 8. Discharge .................................................................................................................................................................... 135 9. Quality Measures ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Bilateral Atraumatic Compartment Syndrome of the Legs Leading to Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Renal Failure Following Prolonged Kneeling in a Heroin Addict

PAJT 10.5005/jp-journals-10030-1075 CASE REPORTBilateral Atraumatic Compartment Syndrome of the Legs Leading to Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Renal Failure Bilateral Atraumatic Compartment Syndrome of the Legs Leading to Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Renal Failure Following Prolonged Kneeling in a Heroin Addict. A Case Report and Review of Relevant Literature Saptarshi Biswas, Ramya S Rao, April Duckworth, Ravi Kothuru, Lucio Flores, Sunil Abrol ABSTRACT cerrado, que interfiere con la circulación de los componentes mioneurales del compartimento. Síndrome compartimental Introduction: Compartment syndrome is defined as a symptom bilateral de las piernas es una presentación raro que requiere complex caused by increased pressure of tissue fluid in a closed una intervención quirúrgica urgente. En un reporte reciente osseofascial compartment which interferes with circulation (Khan et al 2012), ha habido reportados solo 8 casos de to the myoneural components of the compartment. Bilateral síndrome compartimental bilateral. compartment syndrome of the legs is a rare presentation Se sabe que el abuso de heroína puede causar el síndrome requiring emergent surgical intervention. In a recent case report compartimental y rabdomiólisis traumática y atraumática. El (Khan et al 2012) there have been only eight reported cases hipotiroidismo también puede presentarse independiente con cited with bilateral compartment syndrome. rabdomiólisis. Heroin abuse is known to cause compartment syndrome, traumatic and atraumatic rhabdomyolysis. Hypothyroidism can Presentación del caso: Presentamos un caso de una mujer also independently present with rhabdomyolysis. de 22 años quien presentó con tumefacción bilateral de las piernas asociado con la perdida de la sensación, después Case presentation: We present a case of a 22 years old female de pasar dos días arrodillado contra una pared después de who presented with bilateral swelling of the legs with associated usar heroína intravenosa. -

Assessment, Management and Decision Making in the Treatment of Polytrauma Patients with Head Injuries

Compartment Syndrome Andrew H. Schmidt, M.D. Professor, Dept. of Orthopedic Surgery, Univ. of Minnesota Chief, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery Hennepin County Medical Center April 2016 Disclosure Information Andrew H. Schmidt, M.D. Conflicts of Commitment/ Effort Board of Directors: OTA Critical Issues Committee: AOA Editorial Board: J Knee Surgery, J Orthopaedic Trauma Medical Director, Director Clinical Research: Hennepin County Med Ctr. Disclosure of Financial Relationships Royalties: Thieme, Inc.; Smith & Nephew, Inc. Consultant: Medtronic, Inc.; DGIMed; Acumed; St. Jude Medical (spouse) Stock: Conventus Orthopaedics; Twin Star Medical; Twin Star ECS; Epien; International Spine & Orthopedic Institute, Epix Disclosure of Off-Label and/or investigative Uses I will not discuss off label use and/or investigational use in my presentation. Objectives • Review Pathophysiology of Acute Compartment Syndrome • Review Current Diagnosis and Treatment – Risk Factors – Clinical Findings – Discuss role and technique of compartment pressure monitoring. Pathophysiology of Compartment Syndrome Pressure Inflexible Fascia Injured Muscle Vascular Consequences of Elevated Intracompartment Pressure: A-V Gradient Theory Pa (High) Pv (Low) artery arteriole capillary venule vein Local Blood Pa - Pv Flow = R Matsen, 1980 Increased interstitial pressure Pa (High) Tissue ischemia artery arteriole capillary venule vein Lysis of cell walls Release of osmotically active cellular contents into interstitial fluid Increased interstitial pressure More cellular -

Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma: Penetrating Chest Trauma

WTA 2014 ALGORITHM Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma: Penetrating chest trauma Riyad Karmy-Jones, MD, Nicholas Namias, MD, Raul Coimbra, MD, Ernest E. Moore, MD, 09/30/2020 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== by http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma from Downloaded Martin Schreiber, MD, Robert McIntyre, Jr., MD, Martin Croce, MD, David H. Livingston, MD, Jason L. Sperry, MD, Ajai K. Malhotra, MD, and Walter L. Biffl, MD, Portland, Oregon Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma his is a recommended algorithm of the Western Trauma Historical Perspective TAssociation for the acute management of penetrating chest The precise incidence of penetrating chest injury, varies injury. Because of the paucity of recent prospective randomized depending on the urban environment and the nature of the trials on the evaluation and management of penetrating chest review. Overall, penetrating chest injuries account for 1% to injury, the current algorithms and recommendations are based 13% of trauma admissions, and acute exploration is required in by on available published cohort, observational and retrospective BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== 5% to 15% of cases; exploration is required in 15% to 30% of studies, and the expert opinion of the Western Trauma Asso- patients who are unstable or in whom active hemorrhage is ciation members. The two algorithms should be reviewed in the suspected. Among patients managed by tube thoracostomy following sequence: Figure 1 for the management and damage- alone, complications including retained hemothorax, empy- control strategies in the unstable patient and Figure 2 for the ema, persistent air leak, and/or occult diaphragmatic injuries management and definitive repair strategies in the stable patient.