“Eradication of Untouchability” (A Case Study of Post Independent Karnataka)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Employees Details (1).Xlsx

Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services, KALABURGI District Super Specialities ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. Namdev Rathod Assistant Director 08472-226139 9480688435 Veterinary Hospital CompoundSedam Road Kalaburagi pin Cod- 585101 Veterinary Hospitals ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. M.S. Gangnalli Assistant Director 08470-283012 9480688623 Veterinary Hospital Afzalpur Bijapur Road pin code:585301 Assistant Director 2 Dr. Sanjay Reddy (Incharge) 08477-202355 94480688556 Veterinary Hospital Aland Umarga Road pin code: 585302 3 Dr. Dhanaraj Bomma Assistant Director 08475-273066 9480688295 Veterinary Hospital Chincholi pincode: 585307 4 Dr. Basalingappa Diggi Assistant Director 08474-236226 9590709252 Veterinary Hospital opsite Railway Station Chittapur pincode: 585211 5 Dr. Raju B Deshmukh Assistant Director 08442-236048 9480688490 Veterinary Hospital Jewargi Bangalore Road Pin code: 585310 6 Dr. Maruti Nayak Assistant Director 08441-276160 9449618724 Veterinary Hospital Sedam pin code: 585222 Mobile Veterinary Clinics ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. Telephone Nos. Postal Address with No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Fax Mobile 1 Dr. Kimmappa Kote CVO 08470-283012 9449123571 Veterinary Hospital Afzalpur Bijapur Road pin code:585301 2 Dr. sachin CVO 08477-202355 Veterinary Hospital Aland Umarga Road pin code: 585302 3 Dr. Mallikarjun CVO 08475-273066 7022638132 Veterinary Hospital At post Chandaput Tq: chincholi pin code;585305 4 Dr. Basalingappa Diggi CVO 08474-236226 9590709252 Veterinary Hospital Chittapur 5 Dr. Subhaschandra Takkalaki CVO 08442-236048 9448636316 Veterinary Hospital Jewargi Bangalore Road Pin code: 585310 6 Dr. Ashish Mahajan CVO 08441-276160 9663402730 Veterinary Hospital Sedam pin code: 585222 Veterinary Hospitals (Hobli) ANIMAL HUSBANDRY Sl. -

Table of Content Page No's 1-5 6 6 7 8 9 10-12 13-50 51-52 53-82 83-93

Table of Content Executive summary Page No’s i. Introduction 1-5 ii. Background 6 iii. Vision 6 iv. Objective 7 V. Strategy /approach 8 VI. Rationale/ Justification Statement 9 Chapter-I: General Information of the District 1.1 District Profile 10-12 1.2 Demography 13-50 1.3 Biomass and Livestock 51-52 1.4 Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography 53-82 1.5 Soil Profile 83-93 1.6 Soil Erosion and Runoff Status 94 1.7 Land Use Pattern 95-139 Chapter II: District Water Profile: 2.1 Area Wise, Crop Wise irrigation Status 140-150 2.2 Production and Productivity of Major Crops 151-158 2.3 Irrigation based classification: gross irrigated area, net irrigated area, area under protective 159-160 irrigation, un irrigated or totally rain fed area Chapter III: Water Availability: 3.1: Status of Water Availability 161-163 3.2: Status of Ground Water Availability 164-169 3.3: Status of Command Area 170-194 3.4: Existing Type of Irrigation 195-198 Chapter IV: Water Requirement /Demand 4.1: Domestic Water Demand 199-200 4.2: Crop Water Demand 201-210 4.3: Livestock Water Demand 211-212 4.4: Industrial Water Demand 213-215 4.5: Water Demand for Power Generation 216 4.6: Total Water Demand of the District for Various sectors 217-218 4.7: Water Budget 219-220 Chapter V: Strategic Action Plan for Irrigation in District under PMKSY 221-338 List of Tables Table 1.1: District Profile Table 1.2: Demography Table 1.3: Biomass and Live stocks Table 1.4: Agro-Ecology, Climate, Hydrology and Topography Table 1.5: Soil Profile Table 1.7: Land Use Pattern Table -

Respondent College Wise Situation of Campus Democracy

1 2 Acknowledgements esearch Associate Madhu S led this study under the guidance of D Dhanuraj and Prasant Jena. Special thanks to Lakshmi Ramamurthy for R undertaking the data analysis and graphical representation. Gincy Jose and Archana Gayen for editing and formatting, Prof K C Abraham Jiyad K.M, Jithin Paul Varghese, Saritha Varma and Shahnaz for their valuable contribution require a sincere acknowledgement. We extend sincere regards to the LYF core team which was instrumental in designing the study -- Yavnika Khanna, Swati Chawla, Rajan Kumar Singh, Shabi Hussain, Jasmine Jose and Ranjan Baruah. We also extend our sincere appreciation to Nupur Hasija, Saurabh Sharma, Manali Shah and Dr. Parth Shah for their constant support and well wishes. We sincerely thank all the educational institutions which cooperated and provided us the details for the successful completion of the study. We extend our gratitude to all the faculty members and management teams of respondent institutions for helping us with the Study, specifically Dr Soumanyetra Munshi, Assistant Professor at Indian Institute for Management Bangalore for her write- up. Special thanks to Anoop Awasthi (for his valuable contribution on Delhi University elections), Dileep V of Deogiri College, Aurangabad; Mahesh R of Delhi University; Abhinav Pratap Singh of Lucknow University, Richard Haloi of Nagaland, Ratheesh K of Guwahati University and Abin Thomas of Hyderabad University. We are grateful to our reviewers, Mohit Satyanand, Anjana Neira Dev, Nita N Kumar, Rita Sinha and Sumati Panniker. We extend our sincere gratitude to the teams at Liberal Youth Forum, Civitas Consultancy and Frederich Naumann Foundation who supported, ideated conceptualized and carried out the study. -

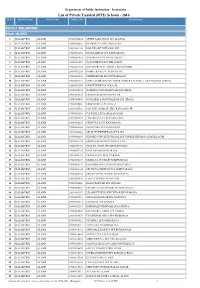

List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No

Department of Public Instruction - Karnataka List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No. District Name Block Name DISE Code School Name Distirct :KALABURGI Block :ALAND 1 KALABURGI ALAND 29040100204 SHREE SARASWATI LPS ALANGA 2 KALABURGI ALAND 29040100603 JNANODAYA HPS AMBALAGA 3 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101102 MALLIKARJUN HPS BOLANI 4 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101202 JNANAAMRAT LPS BANGARAGA 5 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101408 BASAWAJYOTI LPS BELAMAGI 6 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101409 NAVACHETAN LPS BELAMAGI 7 KALABURGI ALAND 29040101908 MATOSHRI NEELAMBIKA BHUSANOOR 8 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103204 INDIRA(KAN)LPS.DHANGAPUR 9 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103310 VEERESHWAR LPS DUTTARGAON 10 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103311 SHREE SIDDESHWAR LOWER PRIMARY SCHOOL LAD CHINCHOLI CROSS 11 KALABURGI ALAND 29040103505 SHANTINIKETAN GOLA (B) 12 KALABURGI ALAND 29040104105 RAMLING CHOUDESHWARI LPS HIROL 13 KALABURGI ALAND 29040104404 SIDDESHWAR HPS HODULUR 14 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105405 SUSILABAI S MANTHALKAR LPS JIDAGA 15 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105406 SIDDASHREE LPS JIDAGA 16 KALABURGI ALAND 29040105503 S.R.PATIL SMARAK HPS KADAGANCHI 17 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106203 C.B.PATIL LPS KAMALANAGAR 18 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106304 LOKAKALYAN LPS KAWALAGA 19 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106305 CHANUKYA LPS KAWAKAGA 20 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106604 NIJACHARANE HPS KHAJURI 21 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106608 SIR M VISHWESHWARAYYA LPS 22 KALABURGI ALAND 29040106609 OXFORD CONVENT SCHOOL LPS VENKTESHWAR NAGAR KHAJURI 23 KALABURGI ALAND 29040107102 SIDDESHWAR HPS KINNISULTAN 24 KALABURGI ALAND 29040107103 -

Remarks Afzalpur Page 1 of 55 04/04/2019

List of Cancellation of Polling Duty S. No. Letter No. Name Designation Department Emp. ID S/W/DO Reason for cancellation Office Class remarks Rehearsal Centre Code: 1 Assembly Segment under which centre falls Afzalpur 139750 AMARNATH DHULE ASSISTANT ENGINEER PW-PUBLIC WORKS 1 17004700020002 DEPARTMENT Cancelled by Committee Marriage PRO KUPENDRA DHULE Office of the Executive Engineer, PWP & IWTD ,Division Old Jewargi 143801 SIDRAMAPPA B WALIKAR SERICULTURE INSPECTOR SE-COMMISSIONER FOR 2 17005900020012 SERICULTURE DEVELOPMENT SST TEAM IN AFZALPUR PRO BHIMASYA WALIKAR DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF SERICULTURE 144462 DR SHAKERA TANVEER ASSISTANT PROFESSOR EC-DEPARTMENT OF 3 17001400080012 COLLEGIATE EDUCATION DOUBLE ORDERS PRO MOHAMMED JAMEEL AHMED Government First Grade College Afzalpur 144467 DR MALLIKARJUN M SAVARKAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR EC-DEPARTMENT OF 4 17001400090005 COLLEGIATE EDUCATION EVM NODAL OFFICER IN PRO MADARAPPA AFZALPUR Govt First Grade Colloge Karajagi Tq Afzalpur Dist Gulbarga 144476 NAVYA N LECTURER ET-DEPARTMENT OF 5 17001800010067 TECHNICAL EDUCATION ON MATERNITY LEAVE PRO NARASIMHAREDDY B LECTURER SELECTION GRADE 144569 JALEEL KHAN JUNIOR ENGINEER MR-DEPARTMENT OF MINOR 6 17003800020022 IRRIGATION SECTOR OFFICER IN AFZALPUR PRO OSMAN KHAN Assistant Executive Engineer 144813 HUMERA THASEEN TRAINED GRADUATE TEACHER QE-3201QE0001-BEO AFZALPUR 7 17008300090006 (TGT) Cancelled by Committee UMRAH PRO M A RASHEED TOUR. BLOCK EDUCATIONAL OFFICER AFZALPUR 145726 SHARANABASAPPA DRAWING MASTER QE-DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC 8 17004900540008 -

Government of Karnataka Directorate of Economics and Statistics

Government of Karnataka Directorate of Economics and Statistics Modified National Agricultural Insurance Scheme - GP-wise Average Yield data for 2013-14 Experiments Average Yield District Taluk Gram Panchayath Planned Analysed (in Kgs/Hect.) Crop : JOWAR Irrigated Season RABI 1 Gulbarga 1 Afzalpur 1 Mannur 4 4 848 2 Mashal 4 4 1168 3 Balurgi 4 4 1168 4 Goura (B) 4 4 1115 5 Udachan 4 4 1230 6 Allagi (B) 4 4 1479 7 Revoor (B) 4 4 1639 8 Afzalpur (TP) 4 4 1277 9 Anoor 4 4 1707 10 Kallur 4 4 1440 11 Kognoor 4 4 1558 12 Bhairamadgi 4 4 1150 13 Athnoor 4 4 1690 14 Chowdapur 4 4 1516 15 Devalghanagapur 4 4 1135 16 Bandarwad 4 4 1188 17 Hasargundagi 4 4 852 2 Aland 18 Belamagi 4 4 2463 19 Tadkal 4 4 2248 20 Niragudi 4 4 2441 21 Jidaga 4 4 2340 22 Madanhipparaga 4 4 2511 23 Narona 4 4 2459 Page 1 of 7 Experiments Average Yield District Taluk Gram Panchayath Planned Analysed (in Kgs/Hect.) 3 Jewargi 24 Nelogi 4 4 2029 25 Kallur (K) 4 4 2095 26 Hipparga (SN) 4 4 2121 27 Kuknoor 4 4 1841 28 Yadrami 4 4 2011 29 Malli 4 4 1867 30 Wadgera 4 4 1814 31 Kuralgera 4 4 1887 32 Magangera 4 4 1898 33 Aralagundagi 4 4 1889 34 Kadakol 4 4 1880 35 Mandewal 4 4 2345 36 Jeratagi 4 4 2095 37 Ankalaga 4 4 2235 38 Itaga 4 4 2406 Page 2 of 7 Experiments Average Yield District Taluk Gram Panchayath Planned Analysed (in Kgs/Hect.) Crop : WHEAT Irrigated Season RABI 1 Gulbarga 1 Afzalpur 39 Mannur 4 4 1664 40 Mashal 4 4 1578 41 Balurgi 4 4 1453 42 Goura (B) 4 4 1837 43 Karajagi 4 4 1806 44 Udachan 4 4 1500 45 Allagi (B) 4 4 2307 46 Badadal 4 4 2401 47 Revoor (B) 4 4 1864 -

The Experiences of Dalit Students and Faculty in One Elite University in India an Exploratory Study

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Experiences of Dalit Students and Faculty in one Elite University in India An Exploratory Study Ovichegan, Samson Keyghobad Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to: Share: to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Nov. 2017 This electronic theses or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Title: The Experiences of Dalit Students and Faculty in one Elite University in India: An Exploratory Study Author: Samson Ovichegan The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. -

Emulating Excellence Takeaways for Replication

Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions Government of India CONTENT Preface 6 6 Pradhan Mantri Krishi 79 Sinchayee Yojana 1 Pradhan Mantri Fasal 9 Introduction Bima Yojana Best Practices for Replication Introduction Suggestions for Effective Implementation Best Practices for Replication Case Studies Suggestions for Effective Implementation Case Studies 7 Stand-up India 93 Introduction 2 Promoting Digital Payments 23 Best Practices for Replication Introduction Suggestions for Effective Implementation Best Practices for Replication Case Studies Suggestions for Effective Implementation Case Studies 8 Startup India 107 Introduction 3 Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana 37 Best Practices for Replication Introduction Suggestions for Effective Implementation Best Practices for Replication Case Studies Suggestions for Effective Implementation Case Studies 9 Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram 125 Jyoti Yojana 4 Deen Dayal Upadhyaya 57 Introduction Grameen Kaushalya Yojana Best Practices for Replication Introduction Suggestions for Effective Implementation Best Practices for Replication Case Studies Suggestions for Effective Implementation Case Studies 5 e–National Agriculture Market 67 Introduction Best Practices for Replication Suggestions for Effective Implementation Case Studies 1. PRADHAN MANTRI FASAL BIMA YOJANA Priority Programme for Prime Minister’s Awards 2017 and 2018 PMFBY | PMFBY | 1.1 INTRODUCTION Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) is a crop The focus areas with regards to -

Crowd Sourcing (Authoritative) of Geographic Information on Public Assets and Amenities H

ISSN: 2319-5967 ISO 9001:2008 Certified International Journal of Engineering Science and Innovative Technology (IJESIT) Volume 2, Issue 6, November 2013 Crowd sourcing (Authoritative) of Geographic Information on Public Assets and Amenities H. Hemanth Kumar, Dr. M. Prithviraj, M. J Rathan Raj, Umesh Ghatage and Mohan Kumar. S Karnataka State Council for Science and Technology (KSCST), Indian Institute of Science (IISc) campus, Bangalore-560012, Karnataka, India Abstract — The utilization of geospatial data and services for a wide range of uses has seen a steady growth in recent decade. This has led the administrators and planners to seek and adopt various data capturing devices to collate quality spatial data at micro level. Availability of spatial data at finer resolution is crucial for planning and decision-making at micro level. Based on the felt need, the Council took up a study to assess the capability of crowd sourcing concepts to capture Geospatial Information by authorities on public assets and community resources, to enrich and augment the spatial content of the data. Crowd sourcing through authorized sources enable authoritative data availability at micro level in a short span of time at nominal cost. Mobile application developed on android platform was assessed on two local governments to check spatial accuracy and data capture format. The results are within the acceptable limits. Keywords—Crowd sourcing, Android apps, GPS (Global Positioning System). I. INTRODUCTION Capturing of geographic information (GI) based on crowd sourcing concepts is a participative activity in which generally citizens voluntarily involve in capturing GI sought by crowd sourcer. The Council under the project funded by Karnataka Knowledge Commission, Government of Karnataka planned to initially capture crowd sourced GI on public assets and community resources by training department officials and local youths. -

Karnataka Circle Cycle III Vide Notification R&E/2-94/GDS ONLINE CYCLE-III/2020 DATED at BENGALURU-560001, the 21-12-2020

Selection list of Gramin Dak Sevak for Karnataka circle Cycle III vide Notification R&E/2-94/GDS ONLINE CYCLE-III/2020 DATED AT BENGALURU-560001, THE 21-12-2020 S.No Division HO Name SO Name BO Name Post Name Cate No Registration Selected Candidate gory of Number with Percentage Post s 1 Bangalore Bangalore ARABIC ARABIC GDS ABPM/ EWS 1 DR1786DA234B73 MONU KUMAR- East GPO COLLEGE COLLEGE Dak Sevak (95)-UR-EWS 2 Bangalore Bangalore ARABIC ARABIC GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR3F414F94DC77 MEGHANA M- East GPO COLLEGE COLLEGE Dak Sevak (95.84)-OBC 3 Bangalore Bangalore ARABIC ARABIC GDS ABPM/ ST 1 DR774D4834C4BA HARSHA H M- East GPO COLLEGE COLLEGE Dak Sevak (93.12)-ST 4 Bangalore Bangalore Dr. Dr. GDS ABPM/ ST 1 DR8DDF4C1EB635 PRABHU- (95.84)- East GPO Shivarama Shivarama Dak Sevak ST Karanth Karanth Nagar S.O Nagar S.O 5 Bangalore Bangalore Dr. Dr. GDS ABPM/ UR 2 DR5E174CAFDDE SACHIN ADIVEPPA East GPO Shivarama Shivarama Dak Sevak F HAROGOPPA- Karanth Karanth (94.08)-UR Nagar S.O Nagar S.O 6 Bangalore Bangalore Dr. Dr. GDS ABPM/ UR 2 DR849944F54529 SHANTHKUMAR B- East GPO Shivarama Shivarama Dak Sevak (94.08)-UR Karanth Karanth Nagar S.O Nagar S.O 7 Bangalore Bangalore H.K.P. Road H.K.P. Road GDS ABPM/ SC 1 DR873E54C26615 AJAY- (95)-SC East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak 8 Bangalore Bangalore HORAMAVU HORAMAVU GDS ABPM/ SC 1 DR23DCD1262A44 KRISHNA POL- East GPO Dak Sevak (93.92)-SC 9 Bangalore Bangalore Kalyananagar Banaswadi GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR58C945D22D77 JAYANTH H S- East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak (97.6)-OBC 10 Bangalore Bangalore Kalyananagar Kalyananagar GDS ABPM/ OBC 1 DR83E4F8781D9A MAMATHA S- East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak (96.32)-OBC 11 Bangalore Bangalore Kalyananagar Kalyananagar GDS ABPM/ UR 1 DR26EE624216A1 DHANYATA S East GPO S.O S.O Dak Sevak NAYAK- (95.8)-UR 12 Bangalore Bangalore St. -

Dist Name Taluk Name GP Name New Accoun No Bank Name Branch Name IFSC Code Rel Amount Gulbarga Afzalpur Kallur 1559 Krishna Gram

Dist_name taluk_name GP_name New Accoun no Bank_name Branch name IFSC code rel_amount Gulbarga Afzalpur Kallur 1559 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Kallur 15.00 Gulbarga Afzalpur Ballurgi 30833298777 State Bank of India (SBI) Afzalpur SBIN0011581 10.00 Afzalpur Total 25.00 Gulbarga Aland Darga Sirur 11180276742 State Bank of India (SBI) Madanhipparga SBIN0005981 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Madan Hipparga 11180276731 State Bank of India (SBI) Madanhipparga SBIN0005981 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Koralli 4513 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Bhusnoor 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Khajuri 5034 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Khajuri 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Kavalga 4531 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Bhusnoor 4.00 Gulbarga Aland Kamalanagar 5192 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) V.K.Salgar 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Yalsangi 5086 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Madiyal 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Kadaganchi 10814186702 State Bank of India (SBI) Kadaganchi SBIN0003825 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Alanga 5038 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Khajuri 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Ambalga 3480 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Ladamugali 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Jidaga 17230 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Aland 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Hodloor 5044 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Khajuri 4.00 Gulbarga Aland Belamagi 5209 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) V.K.Salgar 3.00 Gulbarga Aland Chnchansoor 3217 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Chinchansoor 5.00 Gulbarga Aland Bhusnur 4540 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Bhusnoor 4.00 Gulbarga Aland Bhodhan 201 Krishna Grameena bank (KGB) Narona 4.00 Gulbarga Aland Dhangapur 11132157326 State Bank of India (SBI) Nimbarga SBIN0005981 -

Quantifying Spatio-Temporal Changes in Urban Area of Gulbarga City Using Remote Sensing and Spatial Metrics

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 10, Issue 5 Ver. I (May. 2016), PP 44-49 www.iosrjournals.org Quantifying Spatio-Temporal Changes in Urban Area of Gulbarga City Using Remote Sensing and Spatial Metrics # Mrs. ABHILASHA KUMARI*, Dr. SULOCHANA SHEKHAR *Research Scholar, #Associate Professor& Dean School of Earth Sciences Central University of Karnataka Kadaganchi, Aland Road, Kalaburagi Karnataka, India. (ewm.abhilasha&sulogis) @gmail.com Abstract: Due to dramatic increase in urban population and allied urban problems it is essential to have urban planning and management at local level. For this urban planners and decision-makers need efficient tools to quantify, evaluate and compare the impact of alternative plans and designs so that more informed choices can be made. Gulbarga one of the developing city of Karnataka, it is important to know the extent growth rate of the urban area and to know the landscape fragmentation. The objective of the paper is to analyze the extent and rate of spatio-temporal urban growth of Gulbarga city using multi-temporal satellite images and to quantify the spatio-temporal pattern of urban growth and landscape fragmentation using spatial metrics. This identifies the patterns of sprawl and subsequently predicts the nature of future sprawl. This paper also attempts to describe some of the landscape metrics required for quantifying sprawl for Gulbarga region, so that it will help urban planner to plan city as a sustainable city. Keywords:LULC; spatial metrics; remote sensing; urban growth. I. Introduction Urban sprawl is a universal phenomenon which is taking place all over the world and one necessary for human development which has been occurring much faster in developing countries than in developed countries.