Ladino Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume XV Fall 2008 Issue 4

The JournalHALAPID of the Society for Crypto-Judaic Studies Volume XV Fall 2008 Issue 4 Table of Contents From the Editor’s Desk 3 Meetings and Events Sephardic Voices 4 Phoenix Meetings 6 Members Reports Roger Martinez 14 Yvonne Garcia 20 Invited Artist Isabelle Medina Sandoval 22 A Tribute to Cary Herz Mona Hernandez 26 Articles ü Abraham Ben Samuel Zacuto 31 Harry A. Ezratty ü Rodrigo Cota 37 Elaine Wertheimer Book Review 47 2 Winter, 2008, Issue 4 HaLapid: The Journal of the Society for Crypto Judaic Studies ISSN: 1945-4996 Editor: Ron Duncan-Hart Co-Editor: Editorial/Technology: Arthur Benveniste Co-Editor: Scholarly Articles: Abraham D. Lavender Co-Editors: Personal Stories: Kathleen J. Alcalá and Sonya A. Loya Editorial Policy of HaLapid Halapid contributors come from all over the world. The editors respect different national writing styles and, where possible, have left each item in the author’s style. We edit for grammar, spelling and typo- graphical error. Many contributions are memoirs or retelling or family stories and legends. They may or may not be historically accurate although they are indeed valid, sacred memories that have been passed along through time. We do not attempt to change individual perceptions as long as they are reported as such, but we do change obvious misstatements or historical error. We reserve the right to edit material. Opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the Society for Crypto Judaic Stud- ies or HaLapid. Articles from HaLapid may not be reprinted without permission. Submission of Articles HaLapid invites the submission of articles related to the mission of the Society for Crypto Judaic Studies. -

Singing the Memory of Sepharad: Traditional Sephardic Song and Its Interpretation

Singing the Memory of Sepharad: Traditional Sephardic Song and its Interpretation Katerina Garcia Abstract The transmission and interpretation of Sephardic songs is inextricably linked to Sephardic culture, and to this day represents a powerful marker of identity. It is the aim of this article to first contextualise traditional Sephardic song by outlining a brief introduction into the cultural background of the Sephardic Diaspora. Subsequently, I will introduce the various secular forms and genres of Sephardic traditional song, focusing on the modes of their interpretation by both contemporary Sephardic and non-Sephardic musicians. In doing so, I will propose a typology of performance approaches, with regards to the role that the re-imagining of Sepharad as a mythical land of the past plays in this process. Keywords: Sephardic music, Judeo-Spanish song, interpretation Introduction The Sephardic Jews, or Sephardim1, represent the second largest ethnic division within Judaism, the first one being the Ashkenazim, or German and Eastern-European Jews. In the narrowest sense of the term, Sephardim are the descendants of the Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula at the end of the 15th century (Spain, 1492; Portugal, 1496), and those who assimilated culturally to them in the main areas of Sephardic settlement post-1492 The areas of the Sephardic diaspora are indicated in Figure 1: Figure 1 – The Sephardic Diaspora (Sephiha and Weinstock 1997) Ethnomusicology Ireland 5 (2017) Garcia 172 For the present discussion of traditional Sephardic music, only the areas of the Eastern Mediterranean (incl. the present-day state of Israel), the Balkan Peninsula and North Africa (the former Ottoman Empire) are relevant, as it is here that a specific Sephardic language and culture develop. -

Eastern Mediterranean Judeo-Spanish Songs from the EMI Archive Trust (1907-1912)

Eastern Mediterranean Judeo-Spanish Songs from the EMI Archive Trust (1907-1912) Anthology of Music Traditions in Israel The Hebrew University of Jerusalem • The Jewish Music Research Centre 27 Anthology of Music Traditions in Israel • 27 Editor: Edwin Seroussi Eastern Mediterranean Judeo-Spanish Songs from the EMI Archive Trust (1907-1912) Study and commentaries: Rivka Havassy and Edwin Seroussi Research collaborators: Michael Aylward, Joel Bresler, Judith R. Cohen and Risto Pekka Pennanen Jerusalem, 2020 Jewish Music Research Centre, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem The Hebrew University of Jerusalem • Faculty of Humanities Jewish Music Research Centre In collaboration with the National Library of Israel With the support of Centre for Research and Study of the Sephardi and Oriental Jewish Heritage (Misgav Yerushalayim) at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem For additional materials related to this album, see www.jewish-music.huji.ac.il Academic Board of the Jewish Music Research Centre Chairperson: Shalom Sabar Steven Fassberg, Ruth HaCohen, Yossi Maurey, Elchanan Reiner, Eliyahu Schleifer, Assaf Shelleg, Rina Talgam Director: Edwin Seroussi Digital Transfers: SMART LAB, Hayes, Middlesex Digital Editing and Mastering: Avi Elbaz Graphic design: www.saybrand.co.il Cover photograph: Splendid Palace Hotel, Salonika, c. 1910, location of recordings © and P The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 2020 4 Preface In 2008 the Jewish Music Research Centre released a 4 CD package entitled An Early 20th-century Sephardi Troubadour: The Historic Recordings of Haim Effendi of Turkey. Catering to the increasing scholarly and general public interest in the role commercial recordings had on musical traditions from the early twentieth century, that production became a landmark in the revised appreciation of Sephardic music prior to the rapid chain of events leading to the dissolution of the traditional communities that maintained this music. -

Around the Point

Around the Point Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages, Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman, Ber Kotlerman and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5577-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5577-8 CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Around the Point .......................................................................................... 1 Hillel Weiss Medieval Languages and Literatures in Italy and Spain: Functions and Interactions in a Multilingual Society and the Role of Hebrew and Jewish Literatures ............................................................................... 17 Arie Schippers The Ashkenazim—East vs. West: An Invitation to a Mental-Stylistic Discussion of the Modern Hebrew Literature ........................................... -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution Map 0.1

CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Preface and Acknowledgments xiii Introduction Ana Varela-COPYRIGHTED Lago and Phylis Cancilla MATERIAL Martinelli 3 1. Working in AmericaNOT and FORLiving in DISTRIBUTIONSpain: The Making of Transnational Communities among Spanish Immigrants in the United States Ana Varela- Lago 21 2. The Andalucía- Hawaii- California Migration: A Study in Macrostructure and Microhistory Beverly Lozano 66 3. Spanish Anarchism in Tampa, Florida, 1886– 1931 Gary R. Mormino and George E. Pozzetta† 91 viii CONTENTS 4. “Yours for the Revolution”: Cigar Makers, Anarchists, and Brooklyn’s Spanish Colony, 1878– 1925 Christopher J. Castañeda 129 5. Pageants, Popularity Contests, and Spanish Identities in 1920s New York Brian D. Bunk 175 6. Miners from Spain to Arizona Copper Camps, 1880– 1930 Phylis Cancilla Martinelli 206 7. From the Mountains and Plains of Spain to the Hills and Hollers of West Virginia: Spanish Immigration into Southern West Virginia in the Early Twentieth Century Thomas Hidalgo 246 8. “Spanish Hands for the American Head?”: Spanish Migration to the United States and the Spanish State Ana Varela- Lago 285 Postscript. Hidden No Longer: Spanish Migration and the Spanish Presence in the United States Ana Varela- Lago and Phylis Cancilla Martinelli 320 List of Contributors 329 Index 333 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION MAP 0.1. Map of Spain COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION INTRODUCTION Ana Varela- Lago and Phylis Cancilla Martinelli In his book Our America: A Hispanic History of the United States, -

Spain: New Emigration Policies Needed for an Emerging Diaspora

SPAIN: NEW EMIGRATION POLICIES NEEDED FOR AN EMERGING DIASPORA By Joaquín Arango TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION SPAIN New Emigration Policies Needed for an Emerging Diaspora By Joaquín Arango March 2016 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), for its twelfth plenary meeting, held in Lisbon. The meeting’s theme was “Rethinking Emigration: A Lost Generation or a New Era of Mobility?” and this report was among those that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso-American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy. org/transatlantic. © 2016 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: Danielle Tinker, MPI Typesetting: Liz Heimann, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full- text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.migrationpolicy. org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www. migrationpolicy.org/about/copyright-policy. Inquiries can also be directed to [email protected]. Suggested citation: Arango, Joaquín. -

Ian S. Lustick

MIDDLE EAST POLICY, VOL. XV, NO. 3, FALL 2008 ABANDONING THE IRON WALL: ISRAEL AND “THE MIDDLE EASTERN MUCK” Ian S. Lustick Dr. Lustick is the Bess W. Heyman Chair of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of Trapped in the War on Terror. ionists arrived in Palestine in the the question of whether Israel and Israelis 1880s, and within several de- can remain in the Middle East without cades the movement’s leadership becoming part of it. Zrealized it faced a terrible pre- At first, Zionist settlers, land buyers, dicament. To create a permanent Jewish propagandists and emissaries negotiating political presence in the Middle East, with the Great Powers sought to avoid the Zionism needed peace. But day-to-day intractable and demoralizing subject of experience and their own nationalist Arab opposition to Zionism. Publicly, ideology gave Zionist leaders no reason to movement representatives promulgated expect Muslim Middle Easterners, and false images of Arab acceptance of especially the inhabitants of Palestine, to Zionism or of Palestinian Arab opportuni- greet the building of the Jewish National ties to secure a better life thanks to the Home with anything but intransigent and creation of the Jewish National Home. violent opposition. The solution to this Privately, they recognized the unbridgeable predicament was the Iron Wall — the gulf between their image of the country’s systematic but calibrated use of force to future and the images and interests of the teach Arabs that Israel, the Jewish “state- overwhelming majority of its inhabitants.1 on-the-way,” was ineradicable, regardless With no solution of their own to the “Arab of whether it was perceived by them to be problem,” they demanded that Britain and just. -

Association of Jewish Libraries N E W S L E T T E R February/March 2008 Volume XXVII, No

Association of Jewish Libraries N E W S L E T T E R February/March 2008 Volume XXVII, No. 3 JNUL Officially Becomes The National Library of Israel ELHANAN ADL E R On November 26, 2007, The Knesset enacted the “National Li- assistance of the Yad Hanadiv foundation, which previously brary Law,” transforming the Jewish National and University contributed the buildings of two other state bodies: the Knesset, Library (JNUL) at The Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus and the Supreme Court. The new building will include expanded into the National Library of Israel. reading rooms and state-of-the-art storage facilities, as well as The JNUL was founded in 1892 by the Jerusalem Lodge of a planned Museum of the Book. B’nai B’rith. After the first World War, the library’s ownership The new formal status and the organizational change will was transferred to the World Zionist Organization. With the enable the National Library to expand and to serve as a leader opening of the Hebrew University on the Mount Scopus campus in its scope of activities in Israel, to broaden its links with simi- in 1925, the library was reorganized into the Jewish National and lar bodies in the world, and to increase its resources via the University Library and has been an administrative unit of the government and through contributions from Israel and abroad. Hebrew University ever since. With the founding of the State The law emphasizes the role of the Library in using technology of Israel the JNUL became the de facto national library of Israel. -

Comprobados Con Pruebas De Adn Por El Estado De Israel

ORIGENES ISRAELITAS (SEFARDITAS) COMPROBADOS CON PRUEBAS DE ADN POR EL ESTADO DE ISRAEL A Aaron(18)(S) Aarons(18)(S) Abarbanel, Phineas - Comerciante (Merchant)(9) Abarbanel Davids, Moses - Comunidad de Amsterdam (Amsterdam Community)(12)(S) Abdula, Moss - Converso, Venice Ghetto, Italy (5) Abencini, Abraham - Venice Ghetto, Italy (5) Abenacar, Raphael(12)(S) Abenaker, Elias (12)(S) Abendadone,Abraham(18) Abendana, Benjamin - 1634, Venice Ghetto, Italy (5) Abendana, Raphael - Converso, Venice Ghetto, Italy (5) Abenini, Joseph - Venice Gehtto, Italy (5) Abisdid, Isaac (18)(S) Aboab de Fonseca, Isaac - Primer Rabbi En Nueva York (First Rabbi In New York) (1)(7)(S) Aboab de Fonseca, Isaac - Author (3)(S) Aboab, Isaac - Marrano (7) Aboab, Isaac - Rabbi (11)(14)(S) Aboab, Samuel - Rabbi, Venice Ghetto, Italy (5) Aboab de Toledo, Isaac - Rabbi, Emigro A Portugal (Emigrated To Portugal) (6)(S) Aboaf, Abram - De Portugal En El Getto de Venezia (From Portugal In Venice Ghetto) Italy (5)(S) Aboccara(19)(S) Aboulafia - Andalucia, España (Spain) (1)(S) Abrabanel, Isaac - Lider, Activista Politico, Filosofo, Escribio La Respuesta Al Decreto De Expulsion (Leader, Political Activist, Philosopher, Wrote Response To Expulsion Decree) Toledo, España (Spain) (1)(S) Abrabanel, Samuel (1)(S) Abrahams(18)(S) Abravanel - Familia Intelectual, España (Intelectual Family, Spain)(2)(S) Abrines (20)(S) Abu Jinah, Musa (8) Abulafia - De Toledo, España (Toledo, Spain)(1)(S) Abulafia, Abraham (11) Abulker, Isaac - Rabbi (11) Abuttatzirah - Rabbi (11) Acoca (11)(S) Acosta, -

Paths in Education

Introduction ................................................................................... 461 The Knesset ................................................................................... 461 The parties ..................................................................................... 462 The budget ..................................................................................... 467 The local authorities....................................................................... 469 The professional organizations (Teachers' Unions) ....................... 470 The parents..................................................................................... 476 The Academy ................................................................................. 483 The Media ...................................................................................... 487 The State Comptroller .................................................................... 488 Chapter Five: Events that occurred in the Israeli education system and illustrate the policy-making processes .............. 489 Introduction ................................................................................... 489 Problems within the area of social integration in education ........... 489 Integration versus differentiation ................................................... 505 Education in the developmental areas ............................................ 514 The phenomenon of "Bussing" ...................................................... 526 Local government -

Diwan-Flyer-2015 For-Web.Pdf

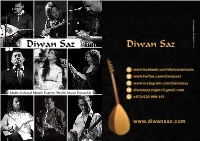

photography: Shmulik Balmas www.facebook.com/diwansazmusic www.twitter.com/diwansaz www.instagram.com/diwansaz Multi-Cultural Middle Eastern World Music Ensemble [email protected] +972-525-999-161 www.diwansaz.com Diwan Saz is a multicultural Jewish ,Christian & Muslim group of musicians who perform ancient music from Central Asia, Turkey, Persia, and the Holy Land - promoting peace and understanding through music. Diwan Saz marries together two great traditions that coexist in the Holy Land - Hebrew and Arab music, The songs are sung together by Rabbi David Menachem , Hamudi Gadir, Tzipora El Rei, lubna sallame & Amir shahsar whose powerful voices, rising at times above the instruments, demands almost undivided attention. Music of peace: The Daly Lama was once asked how to end the conflict between nations and people. He answered, “Through music - playing, learning, and teaching together”. The Diwan Saz Interfaith Ensemble embodies this philosophy photography: Andy Alpern through its repertoire of authentic folk and classical music of the Middle East performed by some of the most respected musicians in the region. The ensemble, led by Musical Director and Baglama musician Yohai Barak, has performed in festivals and venues ”But the most inspiring and quite symbolic performance throughout Europe, Israel , India and several prestigious of the night, was given by the Diwan Saz. A group which festivals in the United States and Canada including The South embodies the ideals of the Festival - diversity and mutual By Southwest Music Festival - Austin Texas. As musicians, respect. Diwan Saz marries together two great traditions artists and teachers Diwansaz combine their many years that coexist in the Holy Land - that of Jewish and Muslim of commitment to their art and their communities to bring a music …A true music of peace and harmony. -

Hispanic-Americans and the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar History Theses and Dissertations History Spring 2020 INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) Carlos Nava [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_etds Recommended Citation Nava, Carlos, "INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939)" (2020). History Theses and Dissertations. 11. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_etds/11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) Approved by: ______________________________________ Prof. Neil Foley Professor of History ___________________________________ Prof. John R. Chávez Professor of History ___________________________________ Prof. Crista J. DeLuzio Associate Professor of History INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Dedman College Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in History by Carlos Nava B.A. Southern Methodist University May 16, 2020 Nava, Carlos B.A., Southern Methodist University Internationalism in the Barrios: Hispanic-Americans in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) Advisor: Professor Neil Foley Master of Art Conferred May 16, 2020 Thesis Completed February 20, 2020 The ripples of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) had a far-reaching effect that touched Spanish speaking people outside of Spain.