CHARTERS TOWERS and the BOER WAR Joan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College of Medicine and Dentistry Student Accommodation Handbook

COLLEGE OF MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY STUDENT ACCOMMODATION HANDBOOK This handbook provides information on your rights and responsibilities as a resident of the College’s Student Accommodation. Please read the handbook carefully before signing the Residential Code of Conduct, Conditions of Use and House Rules. Respect & Responsibility 1 ABOUT THE ACCOMMODATION The James Cook University College of Medicine and Dentistry manages student accommodation at Alice Springs, Atherton, Ayr, Babinda, Bowen, Charters Towers, Collinsville, Cooktown, Darwin, Dysart, Ingham, Innisfail, Mackay, Marreba, Moranbah, Mossman, Proserpine, Sarina, Thursday Island, Tully & Weipa. Regulations and guidelines The regulations of the College of Medicine and Dentistry Student Accommodation are designed to allow the maximum personal freedom within the context of community living. By accepting residency, you agree to comply with these conditions and other relevant University statutes, policies and standards for the period of occupancy. It is expected that Accommodation residents will be responsible in their conduct and will respect all amenities and equipment. Disciplinary processes are in place although it is hoped that these will rarely need to be used. Accommodation Managers The Accommodation Manager is responsible for all matters pertaining to the efficient and effective operation of the College Accommodation within the framework of JCU and College Polices and Regulations. The College Accommodation staff have a responsibility for the wellbeing and safety of all residents -

Reef Guardian Councils of the Great Barrier Reef Catchment

145°E 150°E 155°E S S ° ° 0 0 1 1 Torres Shire Council Northern Peninsular Area Regional Council Reef Guardian Councils of the Great Barrier Reef Catchment Reef Guardian Councils and Local Government Areas ! Captain Billy Landing Area of the Great Barrier Reef Catchment 424,000 square kilometres %% G BGRBMRMP P LocLaolc Galo Gveorvnemrnemnte nAtr eAarea CaCtachtcmhmenetnt Lockhart River Aboriginal Shire Council BBAANNAANNAA S SHHIRIREE 66.7.7 BBAARRCCAALLDDININEE R REEGGIOIONNAALL 33.5.5 LEGEND BBLLAACCKKAALLLL T TAAMMBBOO R REEGGIOIONNAALL 00.2.2 Coral Sea BBUUNNDDAABBEERRGG R REEGGIOIONNAALL 11.5.5 BBUURRDDEEKKININ S SHHIRIREE 11.2.2 Reef Guardian Council CCAAIRIRNNSS R REEGGIOIONNAALL 00.4.4 Reef Guardian Council area CCAASSSSOOWWAARRYY C COOAASSTT R REEGGIOIONNAALL 11.1.1 CENTRAL HIGHLANDS REGIONAL 14.1 extending beyond the Great CENTRAL HIGHLANDS REGIONAL 14.1 CCHHAARRTTEERRSS T TOOWWEERRSS R REEGGIOIONNAALL 1144.9.9 Barrier Reef Catchment boundary CCHHEERRBBOOUURRGG A ABBOORRIGIGININAALL S SHHIRIREE 00.0.0 Local Government Area CCOOOOKK S SHHIRIREE 99.1.1 boundary DDOOUUGGLLAASS S SHHIRIREE 00.6.6 EETTHHEERRIDIDGGEE S SHHIRIREE 00.1.1 Coen ! Great Barrier Reef FFLLININDDEERRSS S SHHIRIREE 00.1.1 ! Port Stewart Marine Park boundary FFRRAASSEERR C COOAASSTT R REEGGIOIONNAALL 11.1.1 GGLLAADDSSTTOONNEE R REEGGIOIONNAALL 22.4.4 Indicative Reef boundary GGYYMMPPIEIE R REEGGIOIONNAALL 11.5.5 HHININCCHHININBBRROOOOKK S SHHIRIREE 00.7.7 Hope Vale Great Barrier Reef Aboriginal Shire Council HHOOPPEE V VAALLEE A ABBOORRIGIGININAALL S SHHIRIREE -

12 Days the Great Tropical Drive

ITINERARY The Great Tropical Drive Queensland – Cairns Cairns – Cooktown – Mareeba – Undara – Charters Towers – Townsville – Ingham – Tully/Mission Beach – Innisfail – Cairns Drive from Cairns to Townsville, through World Heritage-listed reef and rainforests to golden outback savannah. On this journey you won’t miss an inch of Queensland’s tropical splendour. AT A GLANCE Cruise the Great Barrier Reef and trek the ancient Daintree Rainforest. Connect with Aboriginal culture as you travel north to the remote frontier of Cape Tribulation. Explore historic gold mining towns and the lush orchards and plantations of the Tropical Tablelands. Day trip to Magnetic, Dunk and Hinchinbrook Islands and relax in resort towns like Port Douglas and Mission Beach. This journey has a short 4WD section, with an alternative road for conventional vehicles. > Cairns – Port Douglas (1 hour) > Port Douglas – Cooktown (3 hours) > Cooktown – Mareeba (4.5 hours) DAY ONE > Mareeba – Ravenshoe (1 hour) > Ravenshoe – Undara Volcanic Beach. Continue along the Cook Highway, CAIRNS TO PORT DOUGLAS National Park (2.5 hours) Meander along the golden chain of stopping at Rex Lookout for magical views over the Coral Sea beaches. Drive into the > Undara Volcanic National Park – beaches stretching north from Cairns. Surf Charters Towers (5.5 hours) at Machans Beach and swim at Holloways sophisticated tropical oasis Port Douglas, and palm-fringed Yorkey’s Knob. Picnic which sits between World Heritage-listed > Charters Towers – Townsville (1.5 hours) beneath sea almond trees in Trinity rainforest and reef. Walk along the white Beach or lunch in the tropical village. sands of Four Mile Beach and climb > Townsville – Ingham (1.5 hours) Flagstaff Hill for striking views over Port Hang out with the locals on secluded > Ingham – Cardwell (0.5 hours) Douglas. -

Agenda for CTRC General Meeting 27 January 2021

NOTICE OF GENERAL MEETING Dear Councillors, Notice is hereby given of a General Meeting of the Charters Towers Regional Council to be held Wednesday 27 January 2021 at 9:00am at the CTRC Gold & Beef Room 12 Mosman Street, Charters Towers. A Johansson Chief Executive Officer Local Government Regulation 2012, Chapter 8 Administration Part 2, Division 1A - Local government meetings and committees “254I Meetings in public unless otherwise resolved A local government meeting is open to the public unless the local government or committee has resolved that the meeting is to be closed under section 254J. 254J Closed meetings 1) A local government may resolve that all or part of a meeting of the local government be closed to the public. 2) A committee of a local government may resolve that all or part of a meeting of the committee be closed to the public. 3) However, a local government or a committee of a local government may make a resolution about a local government meeting under subsection (1) or (2) only if its councillors or members consider it necessary to close the meeting to discuss one or more of the following matters— a) the appointment, discipline or dismissal of the chief executive officer; b) industrial matters affecting employees; c) the local government’s budget; d) rating concessions; e) legal advice obtained by the local government or legal proceedings involving the local government including, for example, legal proceedings that may be taken by or against the local government; f) matters that may directly affect the health and safety of an individual or a group of individuals; g) negotiations relating to a commercial matter involving the local government for which a public discussion would be likely to prejudice the interests of the local government; h) negotiations relating to the taking of land by the local government under the Acquisition of Land Act 1967; i) a matter the local government is required to keep confidential under a law of, or formal arrangement with, the Commonwealth or a State. -

Charters Towers Regional Council Major Projects Community Update

Major Initiatives for Council Assets and Infrastructure Projects • Council has an extensive list of projects that have been identified by previous Councils and the Community over the past years. • Projects include such things as the Mosman Creek Corridor and Towers Hill, the Wildlife Sanctuary, CTAP – Charters Towers Agriculture Precinct to name a few • Projects have been categorised into:- Lifestyle, Tourism, Economy, Council Infrastructure • The purpose of this presentation is to provide an update of the projects for your information Administration Centre Development Development of Community Hub • Council purchased the residence adjacent to the Library for the purpose of creating additional car parking and to provide additional community space in the library precinct. • The proposal for a community hub has been identified and needs to be further considered before any further development is undertaken. Pioneer Cemetery • Memorial Wall • Restoration of headstones, monuments etc. Motor Sports Complex Unlocking USL Land for development • USL – Unallocated State Land • There are a number of parcels of land (USL) that are suitable for further development for residential purposes in Charters Towers • Council has been working with the State Government in relation to some of these parcels of land to prepare for any required increased development within Charters Towers as a consequence of other developments i.e. increase in mining and agriculture development requiring additional workers and people wanting to relocate to Charters Towers • This -

Charters Towers Meat Processing Facility Overview 2020

Charters Towers is a region of economic strength and economic opportunity. Our future holds the promise of growth, prosperity, and resilience. It is our community that transforms economic potential into economic value. As workers, entrepreneurs, business-owners, volunteers, students, and leaders, our people make Charters Towers an economic destination. Here in Charters Towers we welcome all those who wish to help build our future economy. Our region is a great place to live, to work, to invest, and to do business. New ideas, new residents, new investment, new ventures will drive future economic growth. We are open for business, and ready to work together. Our economic pillars - agriculture, mining, education and tourism - will continue to support the Charters Towers economy. We stand ready to build and expand, to diversify and grow, to create and nurture new industries and jobs. Cr Frank Beveridge Mayor - Charters Towers Regional Council Kilometres With increasing cattle turnoff in northern Queensland, the opportunity exists for a new processor to capitalise on the Asian demand growth. The two existing basic paths to market (via processors in south eastern Queensland, and live export) involve the transport of live cattle over long distances. The Port of Brisbane is 1300 km south of Townsville. Charters Towers is strategically located within the prime cattle growing area of North Queensland and benefits from its location at the crossroads of all major highways in and out of the northern region. A processing facility at Charters Towers will significantly reduce the travel distances for cattle processors, reducing costs to processors and increasing producer revenue in return. -

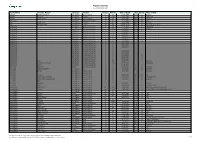

Register of Burials As at 6 December 2019

Register of Burials as at 6 December 2019 Family Name Christian Names Cemetery Division Section Plot No Date of Death Age Gender Place of Birth ABBOTT BEATRICE MARY M New Ingham Roman Catholic 36 56 16/02/1989 75 F ST KILDA ABBOTT CHARLES Old Ingham Anglican 0 1,294 12/05/1939 0 M UNKNOWN ABBOTT HENRY TERRY New Ingham Roman Catholic 36 55 8/04/1997 85 M INGHAM ABDOOLAH Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 52 12/11/1903 55 M INDIA ABEL ISABEL JANE New Ingham Anglican 17 921 24/06/2008 84 F INGHAM ABEL ROY OSBOURNE New Ingham Anglican 17 922 20/02/2016 88 M Townsville, Queensland ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 122 17/12/1911 0 F UNKNOWN ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 529 8/04/1925 0 F INGHAM ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 16/05/1916 0 F ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 26/06/1916 0 M ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 10/03/1917 0 F ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 29/04/1917 0 F ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 28/10/1917 0 M ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 19/07/1919 0 M ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 22/07/1919 0 M ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 30/07/1919 0 ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 4/08/1919 0 ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 0 ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 20/12/1922 0 F ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 25/07/1923 0 F ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 20/11/1923 0 M ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 29/01/1924 0 M ABORIGINAL Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 12/04/1924 0 M ABORIGINAL BABY Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 529 8/04/1925 0 F INGHAM ABORIGINAL No Record - Unknown Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 166 24/09/1913 0 UNKNOWN ABORIGINAL ROSIE Old Ingham Mixed Denomination 0 0 14/08/1924 0 F ABRAHAM RICHARD Halifax Mixed Denomination 45 11 10/11/1921 56 M ENGLAND ABRAHAM STANLEY EMMETT New Ingham R.S.L. -

Charters Towers Regional Water Supply Security Assessment C S4881 11/15

Department of Energy and Water Supply Charters Towers Regional water supply security assessment C S4881 11/15 February 2016 This publication has been compiled by the Department of Energy and Water Supply. © State of Queensland, 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have diferent licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Introduction Charters Towers is a regional mining, agriculture and education centre located approximately 133 km southwest of Townsville. Charters Towers is the regional marshalling centre for live cattle exports out of Townsville, and is known as the education centre of the west, with a total of eight schools including three large private boarding schools. The Queensland Government Statistician’s Ofce (QGSO) estimates the total population of Charters Towers will marginally decline from approximately 8414 (June 2015) to approximately 8207 by the mid-2030s. -

The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, Qld. : 1874 - 1954), Thursday 31 May 1888, Page 3

The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, Qld. : 1874 - 1954), Thursday 31 May 1888, page 3 T. Collins, North. Rifle Association B. Charters Towers 30 Queensland Filey, 0. Charters Tower*... ... ... 29 Tlie first meeting of tbe North Queensland T. Mdllcan, Charters Towers 29 Rifle Association was commenced yesterday, C. Joan, Townirille 29 11. at the bifle Range, on Boss Island, and wilt W. Grant, Mackty ... 29 be concluded to-day. Tbe liberal prizes offered by tbe Association bad the effect of 9 o'olock a m. securing a large number of entries for the different events, and the meeting bids fair to ToicmctUe Bulletin. terminate most successfully. At about s quarter put nine, Colonel (French, in opening the meeting, gave an introductory speech, declaring the btnge open. In course of his little remarks he said that should there be any shortcomings in (he management, he trusted they would be overlooked by the competitor,, as this was the first attempt of tha Aisiciation t- at anything of the kind. very thing, how ever, as far as he knew, had been done to make 1 ff tbe meeting go as well as possible, and he trusted it would only be tbe first of a series : .of successful gatherings of the same nature, 'JLt will be seen that yesterday Charters Towers were most decidedly on top, and it will also be ee*n that Colonel French himself shot remarkably wi-lL. The most interesting feature of today's sfcootmg -»ill he Lite Teams' Match, for which there will b« savent^ams competing. The following are the details of the results so far; the prize winners only being given; Itst OF Winxbs ONLY, QTTEBN'S PK.IZB. -

FNQ Charters Towers Region Exploration

The impact of Modern Exploration Science on Overlooked Historical Mineral Fields, Charters Towers District AusIMM Roundup ,Cairns, May 2021 Presenter : Dr Simon Beams. Principal Geologist Terra Search Pty Ltd Far North Queensland Specialists in Mineral Exploration; Geology & Computing How application of State of the Art conventional & innovative exploration techniques are the Bedrock of Modern Scientific Exploration . There is a dominant focus on exploration under deep cover. However,exposed mineral provinces like Charters Towers ,150 years after their discovery , can be Overlooked & Under-Drilled . Examples • Kirk Goldfield /Jones Prospect (Denjim) Removed by Denjim • Mingela Project (Wishbone Gold) • Piccadilly (Cannindah Resources) AusIMM , Far North Queensland Exploration, Cairns , May 2021 EFFECTIVE CONVENTIONAL & INNOVATIVE EXPLORATION TECHNIQUES (1)Sophisticated processing of high quality geophysics data sets –aeromag, radiometrics,gravity etc. (2) Modelling of Intrusive scale mineral systems (3) Identification of hydrothermal channelways by means of alteration & structural mapping supported by : (4) High Resolution Ground Magnetics/Processing, (5) Delineation of multi-element geochemical zoning , Lab & PXRF analyses (6) Sophisticated statistics utilizing powerful Principal Component Analysis (PCA). (7) End result is much more effective drill targeting which can be greatly enhanced with geophysics (EM,IP, etc) AusIMM , Far North Queensland Exploration, Cairns , May 2021 AusIMM , Far North Queensland Exploration, Cairns , May 2021 -

Northern District

© The State of Queensland, 2019 © Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd, 2019 © QR Limited, 2015 Based on [Dataset – Street Pro Nav] provided with the permission of Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd (Current as at 12 / 19), [Dataset – Rail_Centre_Line, Oct 2015] provided with the permission of QR Limited and other state government datasets Disclaimer: While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this data, Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd and/or the State of Queensland and/or QR Limited makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which you might incur as a result of the data being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and for any reason. FAR NORTH DISTRICT 146°0'E 148°0'E H Ro G E S a u u d R n n d la El Arish 8 Bingil Bay o el n B w ger Y 1 n n a Gi E T 0 L w U CASSOWARY COAST Y W R 8 N MAREEBA a L D H r T Koombooloomba L Mission Beach INGHAM r Y REGIONAL COUNCIL a N 0 SHIRE COUNCIL Dam R 1 2 ENVIRONS 216 0 613 # IV 820 2 Wongaling Beach 277 E 2 8 Tully River Station R ! 8206 Lucinda ER " N IV Tully Dunk Island 0 Port R 6 ! 1 S R 20 E ! o 4 Y a M Lucinda d ! ! Hull Heads # O U 82 18°0'S Euramo 04 37 R Y Family Islands 18°0'S 1 D Tully 4 R E TABLELANDS HINCHINBROOK R 2 ! E 8 N Upper Murray Heads R Murrigal V N " I I SHIRE COUNCIL REGIONAL COUNCIL V E ! R D E ! Bermerside -

Townsville North Queensland Economic Snapshot – November 2020

Townsville North Queensland Economic Snapshot – November 2020 TOWNSVILLE NORTH QUEENSLAND QUARTERLY ECONOMIC SNAPSHOT NOVEMBER 2020 MAJOR SPONSOR MAJOR SPONSOR 1 Townsville North Queensland Economic Snapshot – November 2020 TOWNSVILLE NORTH QUEENSLAND NOVEMBER 2020 QUARTERLY ECONOMIC SNAPSHOT The Townsville North Queensland Economic Snapshot provides a regional economic outlook and commentary with key quarterly statistics including unemployment, business confidence, building approvals, property, and tourism. This edition breaks down the Townsville North Queensland region into two Statistical Areas (SA): Townsville SA3 and Charters Towers – Ayr – Ingham SA3. 1 OUTLOOK FOR TOWNSVILLE NORTH QUEENSLAND 1.1 Key Macroeconomic Trends To date, COVID-19 has had significant implications on worldwide health with over one million lives being lost. Strategic lockdowns have been implemented to help stop the spread of COVID-19 and to ease the pressure placed on hospitals and health systems around the globe, but these lockdowns have had considerable impacts on local economies and on international supply chains. Activity increased in May and June as some economies eased their restrictions, with some even allowing international travel. However, not all countries followed suit, with many still cautious about the health implications and the capacity of their hospital systems. Some countries, such as the UK, are reinstating partial lockdowns to moderate second and third wave increases in virus transmission in a bid to ensure hospital systems are not overwhelmed. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts a decline in global growth of 4.4% in 2020, this is a downward revision from the previous June 2020 forecast . There are factors which could result in a change in growth including ongoing outbreaks and subsequent economic and social lockdowns, trade policy uncertainty, geopolitical tensions or a faster return to ‘normal’1.