Download Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minister of the Gospel at Haddington the Life and Work of the Reverend John Brown (1722-1787)

Minister of the Gospel at Haddington The Life and Work of the Reverend John Brown (1722-1787) David Dutton 2018 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wales: Trinity St. David for the degree of Master of Theology in Church History School of Theology, Religious Studies and Islamic Studies Faculty of Humanities and Performing Arts 1 Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. David W Dutton 15 January 2018 2. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in Church History. David W Dutton 15 January 2018 3. This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. David W Dutton 15 January 2018 4. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying, inter- library loan, and for deposit in the University’s digital repository David W Dutton 15 January 2018 Supervisor’s Declaration. I am satisfied that this work is the result of the student’s own efforts. Signed: …………………………………………………………………………... Date: ………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract This dissertation takes a fresh look at the life and work of the Reverend John Brown (1722-1787), minister of the First Secession Church in Haddington and Professor of Divinity in the Associate (Burgher) Synod, who is best known as the author of The Self-Interpreting Bible (1778). -

Coach Welcome Scheme

Coach welcome scheme LIVERPOOL COACH WELCOME There is secure coach parking at the Eco Coach groups can register for a special Visitor Centre alongside the park and ride Coach Welcome, which involves a personal scheme. This includes lounge, kitchen welcome to the city of Liverpool from one and shower facilities for drivers. of our enthusiastic coach hosts, the latest For more information visit www.visitsouthport.com information on what’s on, complimentary or contact Steve Christian on +44 (0)151 934 2319 maps, rest room and refreshment facilities. For drivers, there are coach drop-off WIRRAL COACH WELCOME and pick-up facilities, parking and traffic For a Mersey Ferries river cruise, park at information and refreshments. Woodside Ferry Terminal. Mersey Ferries links There are two locations: Liverpool Cathedral a number of exciting waterfront attractions in the city’s historic Hope Street Quarter, in Liverpool and Wirral, enabling you to and at Liverpool ONE bus station. create flexible days out for your group. We recommend booking at least 10 days in advance. Port Sunlight, a fascinating 19th century garden • LIVERPOOL CATHEDRAL village, is a very popular group travel destination +44 (0)151 702 7284 and home to both the Port Sunlight Museum and [email protected] Lady Lever Art Gallery. There is extensive free coach parking adjacent to the Lady Lever Art Gallery, with • LIVERPOOL ONE BUS STATION the village attractions easily accessible on foot. +44 (0)151 330 1354 [email protected] For more information about these and more visit www.visitwirral.com/visitor-info/group-travel SOUTHPORT COACH WELCOME Coach hosts are available from April to October to meet and greet coach visitors disembarking at the coach drop-off point on Lord Street, adjacent to The Atkinson. -

Student Guide to Living in Liverpool

A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL www.hope.ac.uk 1 LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL CONTENTS THIS IS LIVERPOOL ........................................................ 4 LOCATION ....................................................................... 6 IN THE CITY .................................................................... 9 LIVERPOOL IN NUMBERS .............................................. 10 DID YOU KNOW? ............................................................. 11 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................. 12 HOW TO LIVE IN LIVERPOOL ......................................... 14 CULTURE ....................................................................... 17 FREE STUFF TO DO ........................................................ 20 FUN STUFF TO DO ......................................................... 23 NIGHTLIFE ..................................................................... 26 INDEPENDENT LIVERPOOL ......................................... 29 PLACES TO EAT .............................................................. 35 MUSIC IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 40 PLACES TO SHOP ........................................................... 45 SPORT IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 50 “LIFE GOES ON SPORT AT HOPE ............................................................. 52 DAY AFTER DAY...” LIVING ON CAMPUS ....................................................... 55 CONTACT -

The Emergence of Schism: a Study in the History of the Scottish Kirk from the National Covenant to the First Secession

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bilkent University Institutional Repository THE EMERGENCE OF SCHISM: A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF THE SCOTTISH KIRK FROM THE NATIONAL COVENANT TO THE FIRST SECESSION A Master’s Thesis by RAVEL HOLLAND Department of History İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara September 2014 To Cadoc, for teaching me all the things that didn’t happen. THE EMERGENCE OF SCHISM: A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF THE SCOTTISH KIRK FROM THE NATIONAL COVENANT TO THE FIRST SECESSION Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by RAVEL HOLLAND In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2014 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. ----------------------------- Assoc. Prof. Cadoc Leighton Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. ----------------------------- Asst. Prof. Paul Latimer Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. ----------------------------- Asst. Prof. Daniel P. Johnson Examining Committee Member Approval of the Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences ----------------------------- Prof. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 {\ C, - U 7 (2» OMB NoJU24,0018 (Rev. 10-90) ^ 2280 Ktw^-^J^.———\ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. sW-irTSffuctions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name _____Lower Long Cane Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church and Cemetery other names/site number Long Cane Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church and Cemetery 2. Location street & number 4 miles west of Trov on SR 33-36_______________ not for publication __ city or town Trov___________________________________ vicinity __X state South Carolina code SC county McCormick______ code 065 zip code 29848 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

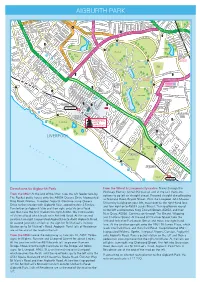

Aigburth Park

G R N G A A O A T D B N D LM G R R AIGBURTHA PARK 5 P R I R M B T 5 R LTAR E IN D D GR G 6 R 1 I Y CO O Superstore R R O 5 V Y 7 N D 2 R S E 5 E E L T A C L 4 A Toxteth Park R E 0 B E P A E D O Wavertree H S 7 A T A L S 8 Cemetery M N F R O Y T A Y E A S RM 1 R N Playground M R S P JE N D K V 9 G E L A IC R R K E D 5 OV N K R R O RW ST M L IN E O L A E O B O A O P 5 V O W IN A U C OL AD T R D A R D D O E A S S 6 P N U E Y R U B G U E E V D V W O TL G EN T 7 G D S EN A V M N N R D 1 7 I B UND A A N E 1 N L A 5 F R S V E B G G I N L L S E R D M A I T R O N I V V S R T W N A T A M K ST E E T V P V N A C Y K V L I V A T A D S R G K W I H A D H K A K H R T C N F I A R W IC ID I A P A H N N R N L L E A E R AV T D E N W S S L N ARDE D A T W D T N E A G K A Y GREENH H A H R E S D E B T B E M D T G E L M O R R Y O T V I N H O O O A D S S I T L M L R E T A W V O R K E T H W A T C P U S S R U Y P IT S T Y D C A N N R I O C H R C R R N X N R RL T E TE C N A DO T E E N TH M 9 A 56 G E C M O U 8 ND R S R R N 0 2 A S O 5 R B L E T T D R X A A L O R BE E S A R P M R Y T Y L A A C U T B D H H S M K RT ST S E T R O L E K I A H N L R W T T H D A L RD B B N I W A LA 5175 A U W I R T Y P S R R I F H EI S M S O Y C O L L T LA A O D O H A T T RD K R R H T O G D E N D L S S I R E DRI U V T Y R E H VE G D A ER E H N T ET A G L Y R EFTO XT R E V L H S I S N DR R H D E S G S O E T T W T H CR E S W A HR D R D Y T E N V O D U S A O M V B E N I O I IR R S N A RIDG N R B S A S N AL S T O T L D K S T R T S V T O R E T R E O A R EET E D TR K A D S LE T T E P E TI S N -

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study..................................................................1 Aigburth....................................................................................................................4 Allerton.....................................................................................................................7 Anfield.................................................................................................................... 10 Broadgreen ............................................................................................................ 12 Childwall................................................................................................................. 14 Clubmoor ............................................................................................................... 16 Croxteth Park ......................................................................................................... 18 Dovecot.................................................................................................................. 20 Everton................................................................................................................... 22 Fairfield ................................................................................................................. -

CHAPTER 4 the 18TH-CENTURY SCOTTISH SERMON : Bk)DES of RHETORIC Ýý B

r CHAPTER 4 THE 18TH-CENTURY SCOTTISH SERMON: bk)DES OF RHETORIC B ýý 18f G Z c9. ;CJ . 'f 259. TILE 18TH-CENTURY SCOTT ISi1 SERMON: )JODES OF RHETORIC Now-a-days, a play, a real or fictitious history, or a romance, however incredible and however un- important the subject may be with regard to the beat interests of men, and though only calculated to tickle a volatile fancy, arcImore valued than the best religious treatise .... This statement in the preface to a Scottish Evangelical tract of the 1770s assembles very clearly the reaction in Evangelical circles to contemporary trends in 18th-century Scottish letters, The movement in favour of a less concen- trated form of religion and the attractions of the new vogue for elegant and melodic sermons were regarded by the majority of Evangelicals as perilous innovations. From the 1750s onwards, the most important task facing Moderate sermon- writers was how to blend the newly-admired concepts of fine feeling and aesthetic taste with a modicum of religious teaching. The writers of Evangelical sermons, on the other hand, remained faithful to the need to restate the familiar tenets of doctrinal faith, often to the exclusion of all else. The Evangelicals regarded the way in which Moderate divines courted fine feeling in their pulpits as both regrettable and ominous. In some quarters, it even assumed the character of a possible harbinger of doom for Scottish prosperity. This reaction on the part of the Evangelicals accounts for the frequent 'alarms' published in connexion with religious topics in 18th-century Scotland. -

The Erskine Halcro Genealogy

u '^A. cpC National Library of Scotland *B0001 37664* Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/erskinehalcrogen1890scot THE ERSKINE-HALCRO GENEALOGY PRINTED FEBRUARY I 895 Impression 250 copies Of which 210 are for sale THE Erskine-Halcro Genealogy THE ANCESTORS AND DESCENDANTS OF HENRY ERSKINE, MINISTER OF CHIRNSIDE, HIS WIFE, MARGARET HALCRO OF ORKNEY, AND THEIR SONS, EBENEZER AND RALPH ERSKINE BY EBENEZER ERSKINE SCOTT A DESCENDANT NEW EDITION, ENLARGED Thefortune of the family remains, And grandsires' grandsires the long list contains. Dryden'S Virgil : Georgic iv. 304. (5 I M EDINBURGH GEORGE P. JOHNSTON 33 GEORGE STREET 1895 Edinburgh : T. and A. Constable, Printers to Her Majesty CONTENTS PAGE Preface to Second Edition, ..... vii Introduction to the First Edition, .... ix List of some of the Printed Books and MSS. referred to, xviii Table I. Erskine of Balgownie and Erskine of Shielfield, I Notes to Table I., 5 Table II. Halcro of Halcro in Orkney, 13 Notes to Table II., . 17 Table III. Stewart of Barscube, Renfrewshire, 23 Notes to Table III., . 27 Table IV. Erskine of Dun, Forfarshire, 33 Notes to Table IV., 37 Table V. Descendants of the Rev. Henry Erskine, Chirnside— Part I. Through his Older Son, Ebenezer Erskine of Stirling, . 41 Part II. Through his Younger Son, Ralph Erskine of Dunfermline, . 45 Notes to Table V., Parts I. and II., 49 — PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION By the kind assistance of friends and contributors I have been enabled to rectify several mistakes I had fallen into, and to add some important information unknown to me in 1890 when the first edition was issued. -

Using Proximate Real Estate to Fund England's Nineteenth Century

Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes An International Quarterly ISSN: 1460-1176 (Print) 1943-2186 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tgah20 Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth? John L. CromptonJOHN L. CROMPTON To cite this article: John L. CromptonJOHN L. CROMPTON (2019): Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth?, Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, DOI: 10.1080/14601176.2019.1638164 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14601176.2019.1638164 Published online: 25 Jul 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tgah20 Using proximate real estate to fund England’s nineteenth century pioneering urban parks: viable vehicle or mendacious myth? john l. crompton It could reasonably be posited that large public urban parks are one of Parliament which was a cumbersome and costly method.1 There were only England’s best ideas and one of its most widely adopted cultural exports. two alternatives. First, there were voluntary philanthropic subscription cam- They were first conceived, nurtured and implemented in England. From paigns that, for example, underwrote Victoria Park which opened in Bath in there they spread to the other UK countries, to the USA, to Commonwealth 1830; Queen’s Park, Philips Park and Peel Park in the Manchester area in the nations, and beyond. -

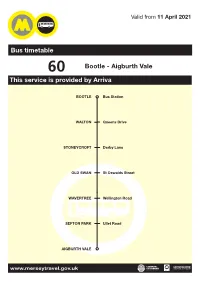

60 Bootle - Aigburth Vale This Service Is Provided by Arriva

Valid from 11 April 2021 Bus timetable 60 Bootle - Aigburth Vale This service is provided by Arriva BOOTLE Bus Station WALTON Queens Drive STONEYCROFT Derby Lane OLD SWAN St Oswalds Street WAVERTREE Wellington Road SEFTON PARK Ullet Road AIGBURTH VALE www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? From Bootle to Aigburth, Mondays-Fridays and Saturdays journeys have minor time changes. The last journey from Bootle Bus Station on Saturday is now half an hour later at 2315. Aigburth to Bootle service hasn’t changed. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Arriva North West 73 Ormskirk Road, Aintree, Liverpool, L9 5AE 0344 800 44 11 or contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call 0151 330 1000, open 0800-2000, 7 days a week. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. Large print timetables We can supply this timetable in another format, such as large print. -

The Forgotten General

FOR REFERENCE Do Not Take From This Room 9 8 1391 3 6047 09044977 7 REF NJ974.9 HFIIfnKi.% SSf?rf?ttr" rn.fg f ° United St.?.. The Forgotten General BY ALBERT H. HEUSSER,* PATERSON, NEW JERSEY Foreword—We have honored Lafayette, Pulaski and Von Steu- ben, but we have forgotten Erskine. No monument, other than a tree planted by Washington beside his gravestone at Ringwood, N. J., has ever been erected to the memory of the noble young Scotchman who did so much to bring the War of the Revolution to a successful issue. Robert Erskine, F. R. S., the Surveyor-General of the Conti- nental Army and the trusted friend of the Commander-in-chief, was the silent man behind the scenes, who mapped out the by-ways and the back-roads over the mountains, and—by his familiarity with the great "middle-ground" between the Hudson Highlands and the Delaware—provided Washington with that thorough knowledge of the topography of the country which enabled him repeatedly to out- maneuver the enemy. It is a rare privilege to add a page to the recorded history of the American struggle for independence, and an added pleasure thereby to do justice to the name of one who, born a subject of George III, threw in his lot with the champions of American lib- erty. Although never participating in a battle, he was the means of winning many. He lost his life and his fortune for America; naught was his reward save a conscience void of offense, and the in- *Mr.