On Thundergods and Thunderbolts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Narrative Volume 1

History into fiction: the metamorphoses of the Mithras myths ROGER BECK Toronto Dedicated to Reinhold Merkelbach, whose explorations of ancient narra- tive and the mystery cults have always seemed to me profoundly well oriented, even when I would not follow the same path in detail. This article is neither about a particular ancient novel nor about the genre of the ancient novel in general. But it is about story-telling in the ancient world, and about the metamorphosis which stories undergo when they pass through the crucible of religious invention. Its subject, then, is narrative fiction — narrative fiction as the construction of sacred myth and of myth’s dramatic counterpart, ritual performance. The fictions I shall explore are the myths and rituals of the Mithras cult. Some of these fictions, I shall argue, are elaborations of events and fantasies of the Neronian age: on the one hand, events in both Italy and the orient cen- tred on the visit of Tiridates of Armenia to Rome in 66; on the other hand, the heliomania of the times, a solar enthusiasm focused on, and in some measure orchestrated by, the emperor himself. What I am not offering is an explanation of Mithraism and its origins. In the first place, our subject is story and the metamorphosis of story, not relig- ion. In the second place, I would not presume to ‘explain’ Mithraism, or any other religion for that matter, by Euhemeristic reduction to a set of historical or pseudo-historical antecedents. In speaking of the ‘invention’ of Mithraism and of its ‘fictions’, moreover, I intend no disrespect. -

Examining the Transference Between Mithraism and Christianity Peter J

\ The Sword and the Cross: Examining the Transference between Mithraism and Christianity Peter J. Decker III Advisor: Dr. Elizabeth Manwell Ph. D .. Kalamazoo College Co-Chair of Classics Department I - A paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degr~e of Bachelor of ~rts at - - Kalamazoo College. 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................... ~ .... : ......................................................ii I. The Cult ofMithras: Imagery, Practices, and Beliefs ............................... .1-21 II. Examining the Transference between Mithraism and Christianity ............... ~ .. 23-38 III. Appendix .......................· ............................................................. 39 Bibliography .................... ·................................................................. 40-44 / 11 Acknowledgements I am deeply grateful to my loving parents who made it possible to attend Kalamazoo College and allow me to further my studies in Classics. Without their financial and emotional support I would not have been able to complete this Senior Independent Project (SIP). Love you Mom and Dad! I am also deepl_y thankful to the Todd family and their generous grant, the Todd Memorial Classics Study Abroad Grant, which allowed me to travel to Italy and gain the inspiration for the topic of my SIP. I would like to express aspecial thanks to my SIP advisor Prof. Manwell, for putting up with all my procrastination and my challenging writing. I hope you didn't spend to many nights up late editing my drafts. Without all of you none of this would have been possible. Thank you very much. 1 I. The Cult ofMithras: Imagery, Practices, and Beliefs In the spring of 2011 an American atheist group put up a billboard in downtown New York City which read: "Born of a virgin on December 25th, known to his 12 disciples as "the Son of God, and resurrected three days after his death, we wish a Happy Birthday to Mithras, the mythical Persian god imagined over 600 years before that other guy .. -

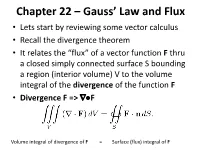

Chapter 22 – Gauss' Law and Flux

Chapter 22 – Gauss’ Law and Flux • Lets start by reviewing some vector calculus • Recall the divergence theorem • It relates the “flux” of a vector function F thru a closed simply connected surface S bounding a region (interior volume) V to the volume integral of the divergence of the function F • Divergence F => F Volume integral of divergence of F = Surface (flux) integral of F Mathematics vs Physics • There is NO Physics in the previous “divergence theorem” known as Gauss’ Law • It is purely mathematical and applies to ANY well behaved vector field F(x,y,z) Some History – Important to know • First “discovered” by Joseph Louis Lagrange 1762 • Then independently by Carl Friedrich Gauss 1813 • Then by George Green 1825 • Then by Mikhail Vasilievich Ostrogradsky 1831 • It is known as Gauss’ Theorem, Green’s Theorem and Ostrogradsky’s Theorem • In Physics it is known as Gauss’ “Law” in Electrostatics and in Gravity (both are inverse square “laws”) • It is also related to conservation of mass flow in fluids, hydrodynamics and aerodynamics • Can be written in integral or differential forms Integral vs Differential Forms • Integral Form • Differential Form (we have to add some Physics) • Example - If we want mass to be conserved in fluid flow – ie mass is neither created nor destroyed but can be removed or added or compressed or decompressed then we get • Conservation Laws Continuity Equations – Conservation Laws Conservation of mass in compressible fluid flow = fluid density, u = velocity vector Conservation of an incompressible fluid = -

Slavic Pagan World

Slavic Pagan World 1 Slavic Pagan World Compilation by Garry Green Welcome to Slavic Pagan World: Slavic Pagan Beliefs, Gods, Myths, Recipes, Magic, Spells, Divinations, Remedies, Songs. 2 Table of Content Slavic Pagan Beliefs 5 Slavic neighbors. 5 Dualism & The Origins of Slavic Belief 6 The Elements 6 Totems 7 Creation Myths 8 The World Tree. 10 Origin of Witchcraft - a story 11 Slavic pagan calendar and festivals 11 A small dictionary of slavic pagan gods & goddesses 15 Slavic Ritual Recipes 20 An Ancient Slavic Herbal 23 Slavic Magick & Folk Medicine 29 Divinations 34 Remedies 39 Slavic Pagan Holidays 45 Slavic Gods & Goddesses 58 Slavic Pagan Songs 82 Organised pagan cult in Kievan Rus' 89 Introduction 89 Selected deities and concepts in slavic religion 92 Personification and anthropomorphisation 108 "Core" concepts and gods in slavonic cosmology 110 3 Evolution of the eastern slavic beliefs 111 Foreign influence on slavic religion 112 Conclusion 119 Pagan ages in Poland 120 Polish Supernatural Spirits 120 Polish Folk Magic 125 Polish Pagan Pantheon 131 4 Slavic Pagan Beliefs The Slavic peoples are not a "race". Like the Romance and Germanic peoples, they are related by area and culture, not so much by blood. Today there are thirteen different Slavic groups divided into three blocs, Eastern, Southern and Western. These include the Russians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Serbians,Croatians, Macedonians, Slovenians, Bulgarians, Kashubians, Albanians and Slovakians. Although the Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians are of Baltic tribes, we are including some of their customs as they are similar to those of their Slavic neighbors. Slavic Runes were called "Runitsa", "Cherty y Rezy" ("Strokes and Cuts") and later, "Vlesovitsa". -

A Reader in Comparative Indo-European Religion

2018 A READER IN COMPARATIVE INDO-EUROPEAN RELIGION Ranko Matasović Zagreb 2018 © This publication is intended primarily for the use of students of the University of Zagreb. It should not be copied or otherwise reproduced without a permission from the author. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations........................................................................................................................ Foreword............................................................................................................................... PART 1: Elements of the Proto-Indo-European religion...................................................... 1. Reconstruction of PIE religious vocabulary and phraseology................................... 2. Basic Religious terminology of PIE.......................................................................... 3. Elements of PIE mythology....................................................................................... PART II: A selection of texts Hittite....................................................................................................................................... Vedic........................................................................................................................................ Iranian....................................................................................................................................... Greek....................................................................................................................................... -

Origins of Hinduism: the Indus Vanev Cmlizauon

Hinduism Indian Religions Name ____________________ Origins of Hinduism: TheIndus vanev CMliZaUon i Hnduism. unlike most majorreligions, does not have a central figure upon whom it is founded. Rather, it is a complex faith with rootsstemming back fivethousand yearsto the people of the Indus Valley, now part of Pakistan. When the Aryan tribesof Persia invaded theIndus Valley around 1700 BCE, the groups' beliefsmerged and Hinduism beganto form. Most of what we know of the Indus people (also called Dravidians)comes fromarchaeological find ings. Artifacts and relics dating back as early as 2000BCE tell the story of a civilization flourishing with craftsmanship, agriculture, and religious life. As··we will see, manyof these earlypractices and beliefsstill shape Hinduism. For example, the Indus put greatimportance on cleanliness or ritual bathing. MohenjoDaro, one of the major Indus cities, contained a huge water tankfor public bathing. Today, many Hindu temples feature such tanks. Another lastinglegacy of Hinduism is foundin the abundanceof terra-cottafigurines unearthed in the Indus Valley. Popular amongthese small ceramicstatuettes were depictions of pregnant women, "mother goddesses." The fertility and strengthof the goddess and the rebirth andcontinuity she pro vides remaincentral to the Hindu faith. Ceramicseals also provideinsight into the Indus' religious beliefs. Among the most common design was that of the bull. It represented virility, or sexual force,which is still consideredsacred to the Hindus. Shiva, among the most revered Hindu gods, is associated with the bull. The Indus were an agriculturalpeople, growing crops and raising animals. Livingon the banks of the Indus River, dependent on its nourishment and renewal, there was deep reverencefor water. -

The Changing Image of Zeus in Olympia

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Judith Barringer The Changing Image of Zeus in Olympia aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue 1 • 2015 Seite / Page 19–37 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa/1911/5932 • urn:nbn:de:0048-journals.aa-2015-1-p19-37-v5932.1 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentrale | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 Verlag / Publisher Ernst Wasmuth Verlag GmbH & Co. Tübingen ©2017 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). Terms of use: By downloading you accept the terms of use (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) of iDAI.publications. -

Apple Thunderbolt Display Teardown Guide ID: 6525 - Draft: 2020-05-25

Apple Thunderbolt Display Teardown Guide ID: 6525 - Draft: 2020-05-25 Apple Thunderbolt Display Teardown Apple Thunderbolt Display Teardown Written By: David Hodson This document was generated on 2020-11-17 05:04:21 PM (MST). © iFixit — CC BY-NC-SA www.iFixit.com Page 1 of 19 Apple Thunderbolt Display Teardown Guide ID: 6525 - Draft: 2020-05-25 INTRODUCTION Crafted from the fire pits of Hephaestus himself, and thrust down to Earth by the mighty Zeus, the Apple Thunderbolt Display arrived at the doorstep of iFixit's headquarters. Follow iFixit on twitter for the latest updates. Cool bonus: Here's a wallpaper of one of Thunderbolt Display's chips, made in the Thunderbolt Display's native 2560 x 1440 resolution. TOOLS: Heavy-Duty Suction Cups (Pair) (1) Spudger (1) T10 Torx Screwdriver (1) T6 Torx Screwdriver (1) This document was generated on 2020-11-17 05:04:21 PM (MST). © iFixit — CC BY-NC-SA www.iFixit.com Page 2 of 19 Apple Thunderbolt Display Teardown Guide ID: 6525 - Draft: 2020-05-25 Step 1 — Apple Thunderbolt Display Teardown By the hammer of Thor! With the new Thunderbolt Display in our hands, the future is looking bright. 27" TFT Active-Matrix LCD 2560 by 1440 Pixel Resolution Built-in Thunderbolt and MagSafe Cables FaceTime HD Camera with Microphone 49 Watt 2.1 Speaker System 16:9 Widescreen Aspect Ratio This document was generated on 2020-11-17 05:04:21 PM (MST). © iFixit — CC BY-NC-SA www.iFixit.com Page 3 of 19 Apple Thunderbolt Display Teardown Guide ID: 6525 - Draft: 2020-05-25 Step 2 The Thunderbolt Display contains a sweet lineup of USB, HDMI, VGA, and DisplayPort ports! Oh wait—wrong thousand-dollar display. -

Thunderbolts’

THE CHANGING MEANING OF ‘THUNDERBOLTS’ Kristiina Johanson Abstract: The article concentrates on the widespread belief in the phenomenon of ‘thunderbolts’. Stone artefacts like Stone Age axes, adzes, chisels, daggers, sickles, spear- and arrowheads as well as Iron Age strike-a-lights are mainly understood by the name ‘thunderbolt’, but no doubt various natural stones of peculiar or unusual shape were believed to have been created by strike of light- ning as well. While corresponding examples of identifying and using ‘thunder- bolts’ are given from different areas of the world, the emphasis is set on the respective Estonian material, introducing both the sources of archaeology as well as of folklore. The author discusses the background and the motifs of the well-known belief in ‘thunderbolts’ and reaches the conclusion that in Estonia it cannot be dated to a period prior to the Pre-Roman Iron Age when stone arte- facts were no longer produced for practical reasons, and it is believed that the motifs of the belief were adopted significantly later, perhaps after the Chris- tianization of the country in the 13th century. Key words: archaeological material, folklore texts on ‘thunderbolts’, history of archaeological thinking, ‘thunderbolt’ belief INTRODUCTION The natives of Burmah, China, Japan [...] think that carved stone objects have fallen from the sky, because they think they have seen such objects fall from the sky. Such objects are called “thunder- bolts” in these countries. They are called “thunderstones” in Mora- via, Holland, Belgium, France, Cambodia, Sumatra, and Siberia. They’re called “storm stones” in Lausitz; “sky arrows” in Slavonia; “thunder axes” in England and Scotland; “lightning stones” in Spain and Portugal; “sky axes” in Greece; “lightning flashes” in Brazil; “thunder teeth” in Amboina.. -

Divine Personality and Personification

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 1 | 1988 Varia Divine Personality and Personification Bernard C. Dietrich Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/77 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.77 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1988 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Bernard C. Dietrich, « Divine Personality and Personification », Kernos [Online], 1 | 1988, Online since 31 January 2011, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/77 ; DOI : 10.4000/kernos.77 Kernos Kernos, 1(1988), p. 19-28. DIVINE PERSONALITY AND PERSONIFICATION The Greeks thought of their gods as personal beings in human shape. They shared their belief in anthropomorphic gods with other and older cultures, sorne of which had contributed to Greek religious thought. But their intense personal quality set the Greek gods apart from others and brought them close to their mortal . subjects. Eastern gods were also conceived of in the image of man but far removed from his level1. The deep gulf between human and divine therefore deprived oriental gods of the most typical and endearing characteristic of the Romeric and Greek Olympians. The Sumerian gods, for example, despite their human shape, remained vasdy superior cosmic powers with only rudimentary persona! characteristics. The gods of Egypt, too, were devoid of personality. The names of most major Egyptian deities are particularly interesting in contrast with Greek practice because their meaning is generally transparent. They translate as divine functions rather than personal tides. They describe the common activity, or nature, of a particular god and not his personality. -

Birth Narratives in Indo-European Mythology

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Birth Narratives in Indo-European Mythology A dissertation submied in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Indo-European Studies by Anna June Pagé 2014 © Copyright by Anna June Pagé 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Birth Narratives in Indo-European Mythology by Anna June Pagé Doctor of Philosopy in Indo-European Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Joseph F. Nagy, Chair is dissertation presents a study of the shared themes and parallel narrative structures of a set of stories about extraordinary birth. Stories about extraordinary birth form a universal story-type that displays widespread and striking similarities in narrative traditions throughout the world. Stories of this nature are typically told about various types of important persons, such as heroes, kings, gods, and saints, and have most frequently been treated within the context of the “heroic biography’’ paern. Because of how well-aested this type of story is in all narrative traditions, a comparison of birth narratives from different Indo-European mythologies offers an ideal case study in the comparison and reconstruction of aspects of the Proto-Indo-European mythological system. While my primary focus is on stories from Indo-European sources, and particularly from Celtic, Greek, and Indic myth, several non-Indo-European examples of this type of narrative are also included in my discussion. e stories under consideration here can be defined as stories that describe a birth (oen including conception and gestation) that in some way or another, and to a greater or lesser extent, deviates from what one would consider a “normal” or “ordinary” birth, from a social or biological standpoint. -

Jupiter's Legacy: the Symbol of the Eagle and Thunderbolt in Antiquity and Their Appropriation by Revolutionary America and Nazi Germany

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2014 Jupiter's Legacy: The yS mbol of the Eagle and Thunderbolt in Antiquity and Their Appropriation by Revolutionary America and Nazi Germany Justin S. Hayes [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Hayes, Justin S., "Jupiter's Legacy: The yS mbol of the Eagle and Thunderbolt in Antiquity and Their Appropriation by Revolutionary America and Nazi Germany" (2014). Senior Capstone Projects. 261. http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/261 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jupiter's Legacy: The Symbol of the Eagle and Thunderbolt in Antiquity and Their Appropriation by Revolutionary America and Nazi Germany Siddhartha Hayes GRST 360-04 Senior Thesis Introduction The thunderbolt and the eagle, the armament and armour-bearer of Jupiter – these symbols had profound cultural significance to the ancients. At first one may think that what was sacred for the Romans has no bearing on modern society, but in truth these icons retain much of their meaning and importance even over two-thousand years later. The Western world has been obsessed with and reverent towards ancient Rome since its fall, and consequently, many different groups have associated themselves with the Latin city and its people, holding aloft its ideas and culture in an attempt to take up the legacy of the “best and greatest” power.