A Prison Chaplaincy Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gotham Knights

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2013 House of Cards Matthew R. Lieber University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Lieber, Matthew R., "House of Cards" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. House of Cards ____________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver ____________________________ In Partial Requirement of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ By Matthew R. Lieber November 2013 Advisor: Sheila Schroeder ©Copyright by Matthew R. Lieber 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Matthew R. Lieber Title: House of Cards Advisor: Sheila Schroeder Degree Date: November 2013 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to approach adapting a comic book into a film in a unique way. With so many comic-to-film adaptations following the trends of action movies, my goal was to adapt the popular comic book, Batman, into a screenplay that is not an action film. The screenplay, House of Cards, follows the original character of Miranda Greene as she attempts to understand insanity in Gotham’s most famous criminal, the Joker. The research for this project includes a detailed look at the comic book’s publication history, as well as previous film adaptations of Batman, and Batman in other relevant media. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 4-2-2016 “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Bosch, Brandon, "“Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films" (2016). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 287. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 37–54 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. -

Duplicity: Exploring the Many Faces of Gotham

Duplicity: Exploring the many faces of Gotham “And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughing stock or a painful embarrassment.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, Also Sprach Zarathustra The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan’s follow up to 2005’s convention- busting Batman Begins, has just broken the earlier box office record set by Spiderman 3 with a massive opening weekend haul of $158 million. While the figures say much about this franchise’s impact on the popular imagination, critical reception has also been in a rare instance overwhelmingly concurrent. What is even more telling is that the old and new opening records were both set by superhero movies. Much has already been discussed in the media about the late Heath Ledger’s brave performance and how The Dark Knight is a gritty new template for all future comic-to-movie adaptations, so we won’t go into much more of that here. Instead, let’s take a hard and fast look at absolutes and motives: old, new, black, white and a few in between. The brutality of The Dark Knight is also the brutality of America post-9/11: the inevitable conflict of idealism and reality, a frustrating political comedy of errors, and a rueful Wodehouseian reconciliation of the improbable with the impossible. Even as the film’s convoluted and always engaging plot breaks down some preconceptions about the psychology of the powerful, others are renewed (at times without logical basis) – that politicians are corruptible, that heroes are intrinsically flawed, that what you cannot readily comprehend is evil incarnate – and it isn’t always clear if this is an attempt at subtle irony or a weary concession to formula. -

Establishment and Implementation of a Conservation and Management Regime for High Seas Fisheries, with Focus on the Southeast Pacific and Chile

ESTABLISHMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF A CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT REGIME FOR HIGH SEAS FISHERIES, WITH FOCUS ON THE SOUTHEAST PACIFIC AND CHILE From Global Developments to Regional Challenges M. Cecilia Engler UN - Nippon Foundation Fellow 2006-2007 ii DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Chile, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan or Dalhousie University. iii iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my profound gratitude to the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), Office of Legal Affairs, United Nations, and the Nippon Foundation of Japan for making this extraordinary and rewarding experience possible. I want to extend my deepest gratitude to the Marine and Environmental Law Institute of Dalhousie University, Canada, and the Sir James Dunn Law Library at the same University Law School, for the assistance, support and warm hospitality provided in the first six months of my fellowship. My special gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Aldo Chircop, for all his guidance and especially for encouraging me to broaden my perspective in order to understand the complexity of the area of research. I would also like to extend my appreciation to those persons who, with no interest but that of helping me through this process, provided me with new insights and perspectives: Jay Batongbacal (JSD Candidate, Dalhousie Law School, Dalhousie University), Johanne Fischer (Executive Secretary of NAFO), Robert Fournier (Marine Affairs Programme, Dalhousie University), Michael Shewchuck (DOALOS), André Tahindro (DOALOS), and David VanderZwaag (Dalhousie Law School, Dalhousie University). -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Marion Prison We Don't Want Lobe Helpless

1HI Sheer hopelessness, llosignalinn You lead il in Ihe faces. Before the fad. hefore CATHOLIC WORKER Hie attempt lo do somcluhtg, all of modem life, at its boiling, tossing center, seems ori;an or tiif. catholic worker imovi.imi.nt hopeless. Acceded, admitted lo, Hie bent TETEn MAUniN. Founder bends, cop-otd, rclrcal. jogging heallh spas, kids' games for adults, homeinaking. DOROTHY DAY, Editor and Publisher money making . Hesislance is hopeless, DANIEl MAUK, PEGGY SCHERER, Managing Editors a wasle. 'They' are loo big. omnivorous, powerful. Our side has no one. no motley, Vol. Xl.iv. No. ? no energy, oleolorn, etcetera. The etceteras September, 1978 would fill a Kelly girl's (sic) wasle haskol with a macho sluller. Marion Prison We don't want lobe helpless. We don'l •• waul to be inarticulate. We don't ward lo be ell the slreef. We tfon'1 wnnf lo sit alone Hell In a Very Small .Space in a box, be shunted around in cuffs. We don'l want lo be losers. We don"! ward to ny DANIEL BEMUGAN. S.J.' selves, we awl the havoc we wreak We, and (he needful victims of--we. die. even a tittle. We want, maybe. In talk Wtffinn nhiwH prisoners is n lilllo like A like fear and trembling arises at (he about the poor, or prisoners, or refugees, nrilitig about the dead: the mass dead, spectacle or political prisoners. To Ihc out or Hie ghotloizod lo write about litem, or lite unknown mid unknowable, limn* killpcl commiserate, or (on occasion) leaflet al a in disasters like Managua or Nagasaki or side worlds, prison is somewhat like a can prison, or-proles! the dentil penally. -

Redeveloping the Distillery District, Toronto

Place Differentiation: Redeveloping the Distillery District, Toronto by Vanessa Kirsty Mathews A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geography University of Toronto © Copyright by Vanessa Kirsty Mathews 2010 Place Differentiation: Redeveloping the Distillery District, Toronto Doctor of Philosophy Vanessa Kirsty Mathews, 2010 Department of Geography University of Toronto Abstract What role does place differentiation play in contemporary urban redevelopment processes, and how is it constructed, practiced, and governed? Under heightened forms of interurban competition fueled by processes of globalization, there is a desire by place- makers to construct and market a unique sense of place. While there is consensus that place promotion plays a role in reconstructing landscapes, how place differentiation operates – and can be operationalized – in processes of urban redevelopment is under- theorized in the literature. In this thesis, I produce a typology of four strategies of differentiation – negation, coherence, residue, multiplicity – which reside within capital transformations and which require activation by a set of social actors. I situate these ideas via an examination of the redevelopment of the Gooderham and Worts distillery, renamed the Distillery District, which opened to the public in 2003. Under the direction of the private sector, the site was transformed from a space of alcohol production to a space of cultural consumption. The developers used a two pronged approach for the site‟s redevelopment: historic preservation and arts-led regeneration. Using a mixed method approach including textual analysis, in-depth interviews, visual analysis, and site observation, I examine the strategies used to market the Distillery as a distinct place, and the effects of this marketing strategy on the valuation of art, history, and space. -

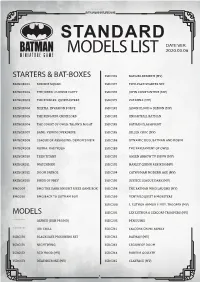

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

Interrogating Religion in Prison: Criminological Approaches

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Social Sciences - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 2014 Interrogating religion in prison: Criminological approaches Natalia K. Hanley University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers Part of the Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hanley, Natalia K., "Interrogating religion in prison: Criminological approaches" (2014). Faculty of Social Sciences - Papers. 2010. https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/2010 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Interrogating religion in prison: Criminological approaches Abstract A preliminary exploration of the contemporary literature on imprisonment and religion suggests three dominant themes: role/effectiveness; risk/security, and human rights. While these themes are interconnected, the literature is broadly characterised by competing and contradictory research questions and conclusions. When taken together, this body of criminological work offers a complex but partial account of the role of religion in contemporary prisons which does not appear to engage with questions about how the provision of religious services is mediated by local prison governance structures. Keywords approaches, criminological, prison, interrogating, religion Disciplines Education | Social and Behavioral Sciences Publication Details -

Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Spectral Science: Into the World of American Ghost Hunters Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3q71q8f7 Author Li, Janny Publication Date 2015 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Spectral Science: Into the World of American Ghost Hunters DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology by Janny Li Dissertation Committee: Chancellor’s Professor George Marcus, Chair Associate Professor Mei Zhan Associate Professor Keith Murphy 2015 ii © 2015 Janny Li ii DEDICATION To My grandmother, Van Bich Luu Lu, who is the inspiration for every big question that I ask. And to My sisters, Janet and Donna Li, with whom I never feel alone in this world. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V CURRICULUM VITAE VII INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: A Case of Quasi-Certainty: William James and the 31 Making of the Subliminal Mind CHAPTER 2: Visions of Future Science: Inside a Ghost Hunter’s Tool Kit 64 CHAPTER 3: Residual Hauntings: Making Present an Intuited Past 108 CHAPTER 4: The Train Conductor: A Case Study of a Haunting 137 CONCLUSION 169 REFERENCES 174 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1. Séance at Rancho Camulos 9 Figure 2. Public lecture at Fort Totten 13 Figure 3. Pendulums and dowsing rods 15 Figure 4. Ad for “Ghost Hunters” 22 Figure 5. Selma Mansion 64 Figure 6. -

Religiousness and Post-Release Community Adjustment Graduate Research Fellowship – Final Report

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Religiousness and Post-Release Community Adjustment Graduate Research Fellowship – Final Report Author(s): Melvina T. Sumter Document No.: 184508 Date Received: September 25, 2000 Award Number: 99-IJ-CX-0001 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. “Religiousness and Post-Release Community Adjustment” Graduate Research Fellowship - Final Report Melvina T. Sumter This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE RELIGIOUSNESS AND POST-RELEASE COMMUNITY ADJUSTMENT BY MELVINA T. SUMTER A Dissertation submitted to the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Degree Awarded: . Fall Semester, 1999 Copyright 0 1999 Melvina T. Sumter All Rights Reserved This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department.