Alcohol Advertising: What Are the Effects?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alcohol Intoxication & Intervention Scale

Alcohol Intoxication & Intervention Scale Alcohol affects each individual differently. The effect of alcohol on a person will vary according to the person's mood, the time of day, Standard Drink amount of food in the stomach, the mixer used, how fast the person One standard drink of beer drinks, and what and why they are drinking. There are a variety of One 12 oz bottle of beer positive and negative consequences related to drinking. One 12 oz can of beer One 8 oz glass of malt liquor (i.e. Blood Alcohol Level Old English, Mickey's) Once you know the definition of one standard drink (see chart to the One standard drink of wine right), you can estimate your Blood Alcohol Level (BAL). BAL levels One 4 oz glass of wine (pictured) represent the percent of your blood that is concentrated with alcohol. A One 3 ‐ 3.5 oz of fortified wine (i.e. BAL of .10 means that .1% of your bloodstream is composed of alcohol. port, sherry) One bottle of table wine is about 5 Some key factors that affect BAL: standard drinks How many standard drinks you drink One standard drink of hard alcohol Remember different drinks have different strengths either One 1.25 oz shot of hard liquor because of differences in proofs of hard liquor or because some (pictured) drinks contain more than one shot One mixed drink containing one 1.25 oz shot of hard liquor Food eaten along with drinking alcohol will result in a lower, One 750ml bottle of hard liquor ("a delayed BAL because the alcohol enters the bloodstream at a fifth") is about 17 standard drinks lower rate Intoxication and Intervention Scale Know the visible signs of intoxication. -

Alcohol Marketing and Advertising, a Report to Congress

Alcohol Marketing and Advertising A Report to Congress September 2003 Federal Trade Commission, 2003 Timothy J. Muris Chairman Mozelle W. Thompson Commissioner Orson Swindle Commissioner Thomas B. Leary Commissioner Pamela Jones Harbour Commissioner Report Contributors Janet M. Evans, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Jill F. Dash, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Neil Blickman, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Enforcement C. Lee Peeler, Deputy Director, Bureau of Consumer Protection Mary K. Engle, Associate Director, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Joseph Mulholland, Bureau of Economics Assistants Dawne E. Holz, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Office of Consumer and Business Education Michelle T. Meade, Law Clerk, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Chadwick Crutchfield, Intern, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Advertising Practices Executive Summary The Conferees of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees directed the Federal Trade Commission to study the impact on underage consumers of ads for new flavored malt beverages, and whether the beverage alcohol industry has implemented the recommendations contained in the Commission’s 1999 report to Congress regarding alcohol industry self- regulation. This report sets forth the Commission’s findings on these subjects. The Commission’s investigation of flavored malt beverages (FMBs) indicates that adults appear to be the intended target of FMB marketing, and that the products have established a niche in the adult market. The investigation found no evidence of targeting underage consumers in the FMB market. FMB marketers placed advertisements in conformance with the industry standard that at least 50% of the advertisement’s audience consists of adults age 21 and over. -

Wine Store/Liquor Store Quick Reference

Wine Store/Liquor Store Quick Reference LICENSING Do I need a wine store/liquor store license? If you intend to sell wine and/or liquor for off premises consumption, you need a wine store or liquor store license.1 Can I be a licensed wine store/liquor store owner in New York State? Statutory Disqualifiers The following are the five categories of person who cannot hold an SLA license: (1) persons who have been convicted of any felony, or promoting or permitting prostitution, or sale of liquor without an alcoholic beverage license;2 (2) persons under the age of 21; (3) persons who are not a United State citizen, an alien admitted to the United State for permanent lawful residence, or a citizen of a reciprocal trade nation (see SLA Advisory #2015-21); (4) persons whose alcoholic beverage license was revoked for cause within the past 2 years; (5) persons who are police officers/police officials. Tied House The “tied house law” prohibits any person who holds a direct or indirect interest in any manufacturing or wholesale business (whether in New York State, another state, or abroad) from holding a wine or liquor store license in New York State. 200 Foot Law The “200 Foot Law” prohibits the Authority from issuing a wine store or liquor store license to any premises which is within 200 feet of and on the same street as a building exclusively used as a school or place of worship. One Store A licensed wine store or liquor store owner may only own or have an interest (direct or indirect) in one wine store or liquor store in New York State. -

South-Florida-Alcohol-Liquor-Licensing-A-Snapshot.Pdf

South Florida Alcohol and Liquor Licensing – A Snapshot By Valerie L. Haber, Miami Alcohol Law and Food Law Attorney Many clients come to GrayRobinson’s Alcohol Law Group with the misconception that getting a beer and wine license, or liquor license in South Florida, (including the City of Miami, Miami Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Broward County or Palm Beach County,) will be a straightforward process. Before reaching out to us, these clients often find themselves stuck in a holding pattern with state or local agencies, which oftentimes have convoluted and burdensome requirements that must be met before a state alcohol license can be issued. Complicating matters further, local municipal requirements vary greatly. For example, the City of Miami Beach, which includes South Beach, requires that you obtain a Certificate of Use and Business Tax Receipt before you can apply for your state alcohol beverage license. The City of Miami, which includes downtown Miami, the Design District, Wynwood, Coconut Grove, and the Calle Ocho area, requires that multiple local inspections be performed before their zoning department will sign off on a state alcohol beverage application. Navigating these complexities can be tough, but completely manageable once you understand important aspects of the licensing process. Florida Liquor License and Beer and Wine License Types: As a starting point, if you are a new business in South Florida wanting to sell alcohol beverages, including beer, wine, or spirits, you need to determine what type of alcohol or liquor license is appropriate for your intended operations. There are multiple Florida alcohol license types available to you through the Florida Division of Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco (the “DABT”), including: Beer and wine for on-premise consumption (2COP license): A “2COP” license allows the licensee to sell beer and wine for on-premise consumption. -

Know Your Liquor VODKA WHISKY

Know Your Liquor VODKA Good to know: Vodka is least likely to give you a hangover Vodka is made by fermenting grains or crops such as potatoes with yeast. It's then purified and repeatedly filtered, often through charcoal, strange as it sounds, until it's as clear as possible. CALORIES: Because vodka contains no carbohydrates or sugars, it contains only calories from ethanol (around 7 calories per gram), making it the least-fattening alcoholic beverage. So a 35ml shot of vodka would contain about 72 calories. PROS: Vodka is the 'cleanest' alcoholic beverage because it contains hardly any 'congeners' - impurities normally formed during fermentation.These play a big part in how bad your hangover is. Despite its high alcohol content - around 40 per cent - vodka is the least likely alcoholic drink to leave you with a hangover, said a study by the British Medical Association CONS: Vodka is often a factor in binge drinking deaths because it is relatively tasteless when mixed with fruit juices or other drinks. HANGOVER SEVERITY: 3/10 WHISKY Good to know: Whisky or Scotch is distilled from fermented grains, such as barley or wheat, then aged in wooded casks. Whisky 'madness': It triggers erratic and unpredictable behaviour because most people drink whisky neat CALORIES: About 80 calories per 35ml shot. PROS: Single malt whiskies have been found to contain high levels of ellagic acid, according to Dr Jim Swan of the Royal Society of Chemists. This powerful acid inhibits the growth of tumours caused by certain carcinogens and kills cancer cells without damaging healthy cells. -

The Beverage Company Liquor List

The Beverage Company Liquor List Arrow Kirsch 750 Presidente Brandy 750 Stirrings Mojito Rimmer Raynal Vsop 750 Glenlivet French Oak 15 Yr Canadian Ltd 750 Everclear Grain Alcohol Crown Royal Special Reserve 75 Amaretto Di Amore Classico 750 Crown Royal Cask #16 750 Amarito Amaretto 750 Canadian Ltd 1.75 Fleishmanns Perferred 750 Canadian Club 750 G & W Five Star 750 Canadian Club 1.75 Guckenheimer 1.75 Seagrams Vo 1.75 G & W Five Star 1.75 Black Velvet Reserve 750 Imperial 750 Canadian Club 10 Yr Corbys Reserve 1.75 Crown Royal 1.75 Kessler 750 Crown Royal W/Glasses Seagrams 7 Crown 1.75 Canadian Club Pet 750 Corbys Reserve 750 Wisers Canadian Whisky 750 Fleishmanns Perferred 1.75 Black Velvet Reserve Pet 1.75 Kessler 1.75 Newport Canadian Xl Pet Kessler Pet 750 Crown Royal 1.75 W/Flask Kessler 375 Seagrams Vo 375 Seagrams 7 Crown 375 Seagrams 7 Crown 750 Imperial 1.75 Black Velvet 375 Arrow Apricot Brandy 750 Canadian Mist 1.75 Leroux Blackberry Brandy 1ltr Mcmasters Canadian Bols Blackberry Brandy 750 Canada House Pet 750 Arrow Blackberry Brandy 750 Windsor Canadian 1.75 Hartley Brandy 1.75 Crown Royal Special Res W/Glas Christian Brothers Frost White Crown Royal 50ml Christian Broyhers 375 Seagrams Vo 750 Silver Hawk Vsop Brandy Crown Royal 375 Christian Brothers 750 Canada House 750 E & J Vsop Brandy Canada House 375 Arrow Ginger Brandy 750 Canadian Hunter Pet Arrow Coffee Brandy 1.75 Crown Royal 750 Korbel Brandy 750 Pet Canadian Rich & Rare 1.75 E&J Brandy V S 750 Canadian Ric & Rare 750 E&J Brandy V S 1.75 Seagrams Vo Pet 750 -

All Night Long: Social Media Marketing to Young People by Alcohol Brands and Venues

All night long: Social media marketing to young people by alcohol brands and venues Professor Christine Griffin, Dr Jeff Gavin and Professor Isabelle Szmigin July 2018 AUTHOR DETAILS Professor Christine Griffin, Department of Psychology, University of Bath, [email protected] Dr Jeff Gavin, Department of Psychology, University of Bath, [email protected] Professor Isabelle Szmigin, Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham, [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research team would like to thank those young people who gave up their time to participate in the focus groups and individual interviews. We would like to thank Alcohol Research UK for funding this research, and especially James Nicholls for his enthusiastic support. We would also like to thank Jemma Lennox, Samantha Garay, Lara Felder and Alexia Pearce for their invaluable work on the project. This report was funded by Alcohol Research UK. Alcohol Research UK and Alcohol Concern merged in April 2017 to form a major independent national charity, working to reduce the harms caused by alcohol. Read more reports at: www.alcoholresearchuk.org Opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. 1 Background and aims ......................................................................................................... 1 Methods ............................................................................................................................... -

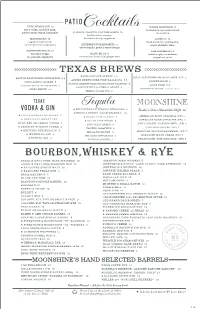

Liquor Menu 3.19

PATIO HARD LEMONADE 10 WHITE LIGHTNING 5 tito’s vodka, muddled mint, Cocktails homemade seasonal infused paula’s texas lemon, lemonade GOOD HEARTED OLD FASHIONED 12 moonshine buffalo trace, orange, MANHATTAN 13 drunken cherry, angostura SAZERAC 14 sagamore spirit rye, knob creek rye, peychaud’s, cocchi di torino, angostura SILVERMOON MARGARITA 8 sugar, absinthe rinse silver tequila, paula’s texas orange SOUTHERN BELLE 12 THE WATERLOO 9 wheatley vodka, BLIND MULE 9 waterloo gin, cucumbers, st. germain, raspberry moonshine, lime juice, ginger beer grapefruit juice <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< TEXAS BREWS <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< KARBACH LOVE STREET 5.5 AUSTIN EASTCIDERS PINEAPPLE 5.5 REAL ALE FIREMANS #4 BLONDE ALE 5 AUSTIN BEERWORKS FIRE EAGLE IPA 5.5 CIRCLE ENVY AMBER 5 SHINER BOCK 5 AUSTIN BEERWORKS PEARL SNAP PILSNER 5 CIRCLE BLUR TEXAS HEFE 5 LONE STAR 3.5 CONVICT HILL OATMEAL STOUT 6 CELIS WHITE 5.5 SEASONAL BREW MARKET PRICE FRESH COAST IPA 6 TEXAS Tequila MOONSHINE ★ VODKA & GIN PEPE ZEVADA Z TEQUILA REPOSADO 8 Dealer’s Choice Moonshine Flight 18 ★ ZEVADA FAMILY “GRAN RESERVA” 12 ★ TITO’S HANDMADE VODKA 7 ★ DULCE VIDA BLANCO 9 AMERICAN BORN ORIGINAL (TN) 8 ★ DEEP EDDY SWEET TEA, ★ DULCE VIDA AÑEJO 9 AMERICAN BORN APPLE PIE (TN) 8 RUBY RED OR LEMON VODKA 7 DON JULIO AÑEJO 9 STILL AUSTIN “DAYDREAMER” (TX) 8 ★ DRIPPING SPRINGS VODKA 8 TANTEO JALAPEÑO 8 CATDADDY SPICED (NC) 7 ★ DRIPPING SPRINGS GIN 8 MILAGRO SILVER 8 MIDNIGHT MOON STRAWBERRY (NC) 7 ★ WATERLOO GIN 8 MILAGRO REPOSADO 8 MIDNIGHT MOON PEACH (NC) 7 ★ ZEPHYR GIN 8 PATRON SILVER -

Alcohol-Free and Low-Strength Drinks

Alcohol-free and low-strength drinks Understanding their role in reducing alcohol-related harms Scott Corfe Richard Hyde Jake Shepherd Kindly supported by ALCOHOL-FREE AND LOW-STRENGTH DRINKS FIRST PUBLISHED BY The Social Market Foundation, September 2020 11 Tufton Street, London SW1P 3QB Copyright © The Social Market Foundation, 2020 ISBN: 978-1-910683-94-1 The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. THE SOCIAL MARKET FOUNDATION The Foundation’s main activity is to commission and publish original papers by independent academics and other experts on key topics in the economic and social fields, with a view to stimulating public discussion on the performance of markets and the social framework within which they operate. The Foundation is a registered charity (1000971) and a company limited by guarantee. It is independent of any political party or group and is funded predominantly through sponsorship of research and public policy debates. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors, and these do not necessarily reflect the views of the Social Market Foundation. CHAIR DIRECTOR Mary Ann Sieghart James Kirkup TRUSTEES Baroness Grender MBE Tom Ebbutt Rt Hon Dame Margaret Hodge MP Peter Readman Melville Rodrigues Trevor Phillips OBE Professor Tim Bale Rt Hon Baroness Morgan of Cotes 1 SOCIAL MARKET FOUNDATION CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... -

Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health WHO Library Cataloguing-In-Publication Data

Global status report on alcohol and health WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Global status report on alcohol and health. 1.Alcoholism - epidemiology. 2.Alcohol drinking - adverse effects. 3.Social control, Formal - methods. 4.Cost of illness. 5.Public policy. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 156415 1 (NLM classification: WM 274) © World Health Organization 2011 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. -

How to Enjoy a Teetotal All-Night Party: Abstinence and Identity at the Sakha People’S Yhyakh

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/FEJF2015.61.peers_kolodeznikov HOW TO ENJOY A TEETOTAL ALL-NIGHT PARTY: ABSTINENCE AND IDENTITY AT THE SAKHA PEOPLE’s YHYAKH Eleanor Peers, Stepan Kolodeznikov Abstract: This paper exploits the interconnections between alcohol use and politics, to examine changing forms of Sakha identification in the Sakha people’s northeast Siberian Republic, Sakha (Yakutia). The Sakha people are an indi- genous Siberian community; their territories have been under Russian adminis- tration since the early seventeenth century. The public event that is this paper’s main focus – the Yhyakh – is a shamanic ritual, which has come to be regarded as a quintessential traditional Sakha practice. Like many other non-Russian communities across the Soviet Union, the Sakha people have been experiencing a cultural revival, in the wake of an intensive attempt at cultural homogenisation during the Soviet era. Moderate Sakha na- tionalist politicians enjoyed a heady period of political dominance during the 1990s, which ceased with the advent of the Putin administrations. The Sakha people have since then watched the political and economic power of the Sakha nationalist movement fade into nothing, as the central government in Moscow has re-asserted its dominance over the Russian Federation’s subject regions. This brief examination of alcohol consumption at the Yhyakh reveals the emergence of new conventions and discussions surrounding pleasure-seeking, physical dis- cipline, and ethnic identification. It shows how the Sakha identification for many has become integrated into projects of personal reformation, as part of a broader acceptance of the Sakha national revival and its aims. The Yhyakh has become a fulcrum for the physical, spiritual and moral aspirations of a nationalist move- ment that can no longer exert a political influence, but is nonetheless capable of shaping aesthetic and moral values, and physical practice. -

Liquor Laws Hawaii

Chapter 281, Hawaii Revised Statutes L i q u o r L aws Of H awa i i City and County of Honolulu Revised April 2016 ● Printed April 2017 April 2016 TITLE 16 INTOXICATING LIQUOR CHAPTER 281 INTOXICATING LIQUOR PART I. GENERAL PROVISIONS .................................................................................................... 1 §281-1 Definitions .......................................................................................................................... 1 §281-2 Excepted articles; penalty ............................................................................................ 5 §281-3 Illegal manufacture, importation, or sale of liquor. .................................................. 6 §281-4 Liquor consumption on unlicensed premises prohibited, when ............................ 6 [§281-5] Powdered alcohol ......................................................................................................... 8 PART II. LIQUOR COMMISSIONS .................................................................................................. 8 §281-11 County liquor commissions and liquor control adjudication boards; qualifications; compensation ....................................................................................... 8 §281-11.5 Liquor commission and board attorney ..................................................................... 9 §281-12 Commission and board office .................................................................................... 10 §281-13 Meeting ..........................................................................................................................