Mangea Hill Forest Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species List (Note, There Was a Pre-Tour to Kenya in 2018 As in 2017, but These Species Were Not Recorded

Tanzania Species List (Note, there was a pre-tour to Kenya in 2018 as in 2017, but these species were not recorded. You can find a Kenya list with the fully annotated 2017 Species List for reference) February 6-18, 2018 Guides: Preston Mutinda and Peg Abbott, Driver/guides William Laiser and John Shoo, and 6 participants: Rob & Anita, Susan and Jan, and Bob and Joan KEYS FOR THIS LIST The # in (#) is the number of days the species was seen on the tour (E) – endemic BIRDS STRUTHIONIDAE: OSTRICHES OSTRICH Struthio camelus massaicus – (8) ANATIDAE: DUCKS & GEESE WHITE-FACED WHISTLING-DUCK Dendrocygna viduata – (2) FULVOUS WHISTLING-DUCK Dendrocygna bicolor – (1) COMB DUCK Sarkidiornis melanotos – (1) EGYPTIAN GOOSE Alopochen aegyptiaca – (12) SPUR-WINGED GOOSE Plectropterus gambensis – (2) RED-BILLED DUCK Anas erythrorhyncha – (4) HOTTENTOT TEAL Anas hottentota – (2) CAPE TEAL Anas capensis – (2) NUMIDIDAE: GUINEAFOWL HELMETED GUINEAFOWL Numida meleagris – (12) PHASIANIDAE: PHEASANTS, GROUSE, AND ALLIES COQUI FRANCOLIN Francolinus coqui – (2) CRESTED FRANCOLIN Francolinus sephaena – (2) HILDEBRANDT'S FRANCOLIN Francolinus hildebrandti – (3) Naturalist Journeys [email protected] 866.900.1146 / Caligo Ventures [email protected] 800.426.7781 naturalistjourneys.com / caligo.com P.O. Box 16545 Portal AZ 85632 FAX: 650.471.7667 YELLOW-NECKED FRANCOLIN Francolinus leucoscepus – (4) [E] GRAY-BREASTED FRANCOLIN Francolinus rufopictus – (4) RED-NECKED FRANCOLIN Francolinus afer – (2) LITTLE GREBE Tachybaptus ruficollis – (1) PHOENICOPTERIDAE:FLAMINGOS -

The Eastern Africa Coastal Forests Ecoregion

The Eastern Africa Coastal Forests Ecoregion Strategic Framework for Conservation 2005 – 2025 Strategic Framework for Conservation (2005–2025) The Eastern Afrca Coastal Forests Ecoregon Strategc Framework for Conservaton 2005–2025 The Eastern Africa Coastal Forests Ecoregion Publshed August 2006 Editor: Kimunya Mugo Design and layout: Anthony Mwangi Cover design: Kimunya Mugo Front cover main photo: WWF-EARPO / John SALEHE Front cover other photos: WWF-UK / Brent STIRTON / Getty Images Back cover photo: WWF-EARPO / John SALEHE Photos: John Salehe, David Maingi and Neil Burgess or as credited. © Graphics (2006) WWF-EARPO. All rights reserved. The material and geographic designations in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. WWF Eastern Africa Regional Programme Office ACS Plaza, Lenana Road P.O. Box 62440-00200 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 3877355, 3872630/1 Fax: +254 20 3877389 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.panda.org/earpo Strategic Framework for Conservation (2005–2025) Contents Acknowledgements......................................................................................................... iv Foreword........................................................................................................................... v Lst of abbrevatons and acronyms.............................................................................. v A new approach to -

Hungary & Transylvania

Although we had many exciting birds, the ‘Bird of the trip’ was Wallcreeper in 2015. (János Oláh) HUNGARY & TRANSYLVANIA 14 – 23 MAY 2015 LEADER: JÁNOS OLÁH Central and Eastern Europe has a great variety of bird species including lots of special ones but at the same time also offers a fantastic variety of different habitats and scenery as well as the long and exciting history of the area. Birdquest has operated tours to Hungary since 1991, being one of the few pioneers to enter the eastern block. The tour itinerary has been changed a few times but nowadays the combination of Hungary and Transylvania seems to be a settled and well established one and offers an amazing list of European birds. This tour is a very good introduction to birders visiting Europe for the first time but also offers some difficult-to-see birds for those who birded the continent before. We had several tour highlights on this recent tour but certainly the displaying Great Bustards, a majestic pair of Eastern Imperial Eagle, the mighty Saker, the handsome Red-footed Falcon, a hunting Peregrine, the shy Capercaillie, the elusive Little Crake and Corncrake, the enigmatic Ural Owl, the declining White-backed Woodpecker, the skulking River and Barred Warblers, a rare Sombre Tit, which was a write-in, the fluty Red-breasted and Collared Flycatchers and the stunning Wallcreeper will be long remembered. We recorded a total of 214 species on this short tour, which is a respectable tally for Europe. Amongst these we had 18 species of raptors, 6 species of owls, 9 species of woodpeckers and 15 species of warblers seen! Our mammal highlight was undoubtedly the superb views of Carpathian Brown Bears of which we saw ten on a single afternoon! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Hungary & Transylvania 2015 www.birdquest-tours.com We also had a nice overview of the different habitats of a Carpathian transect from the Great Hungarian Plain through the deciduous woodlands of the Carpathian foothills to the higher conifer-covered mountains. -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Raptor Road Survey of Northern Kenya 2–15 May 2016

Raptor Road Survey of northern Kenya 2–15 May 2016 Darcy Ogada, Martin Odino, Peter Wairasho and Benson Mugambi 1 Summary Given the rapid development of northern Kenya and the number of large-scale infrastructure projects that are planned for this region, we undertook a two-week road survey to document raptors in this little-studied region. A team of four observers recorded all raptors seen during road transects over 2356 km in the areas of eastern Lake Turkana, Illeret, Huri Hills, Forolle, Moyale, Marsabit and Laisamis. Given how little is known about the biodiversity in this region we also recorded observations of large mammals, reptiles and non-raptorial birds. Our surveys were conducted immediately after one of the heaviest rainy periods in this region in recent memory. We recorded 770 raptors for an average of 33 raptors/100 km. We recorded 31 species, which included two Palaearctic migrants, Black Kite (Milvus migrans) and Montagu’s Harrier, despite our survey falling outside of the typical migratory period. The most abundant raptors were Rüppell’s Vultures followed by Eastern Pale Chanting Goshawk, Hooded Vulture and Yellow-billed Kite (M. migrans parasitus). Two species expected to be seen, but that were not recorded were White-headed Vulture and Secretarybird. In general, vultures were seen throughout the region. The most important areas for raptors were Marsabit National Park, followed by the area from Huri Hills to Forolle and the area south of Marsabit Town reaching to Ololokwe. There was a surprising dearth of large mammals, particularly in Sibiloi and Marsabit National parks, which likely has implications for raptor populations. -

Management Plan of Babile Elephant Sanctuary

BABILE ELEPHANT SANCTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN December, 2010 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Wildlife for Sustainable Authority (EWCA) Development (WSD) Citation - EWCA and WSD (2010) Management Plan of Babile Elephant Sanctuary. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 216pp. Acronyms AfESG - African Elephant Specialist Group BCZ - Biodiversity Conservation Zone BES - Babile Elephant Sanctuary BPR - Business Processes Reengineering CBD - Convention on Biological Diversity CBEM - Community Based Ecological Monitoring CBOs - Community Based Organizations CHA - Controlled Hunting Area CITES - Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora CMS - Convention on Migratory Species CSA - Central Statistics Agency CSE - Conservation Strategy of Ethiopia CUZ - Community Use Zone DAs - Development Agents DSE - German Foundation for International Development EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EPA - Environmental Protection Authority EWA - Ethiopian Wildlife Association EWCA - Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority EWCO - Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Organization EWNHS - Ethiopian Wildlife and Natural History Society FfE - Forum for Environment GDP - Gross Domestic Product GIS - Geographic Information System ii GPS - Global Positioning System HEC – Human-Elephant Conflict HQ - Headquarters HWC - Human-Wildlife Conflict IBC - Institute of Biodiversity Conservation IRUZ - Integrated Resource Use Zone IUCN - International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources KEAs - Key Ecological Targets -

Thése REBBAH Abderraouf Chouaib Bibliothéque.Pdf

République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique Université Larbi Ben M’hidi Oum El Bouaghi Faculté Des Sciences Exactes et des Sciences de la Nature et de la Vie Département des Sciences de la Nature et de la Vie Thèse Présentée en vue de l’obtention du diplôme Doctorat LMD en Sciences de la nature Option: Structure et dynamique des écosystèmes Théme INVENTAIRE ET ECOLOGIE DES OISEAUX FORESTIERS DE DJEBEL SIDI REGHIS (OUM EL BOUAGHI) Présentée par : Mr.REBBAH Abderraouf Chouaib Membres du Jury: Président: BELAIDI Abdelhakim Pr (Université Larbi Ben Mhidi, Oum El-Bouaghi). Promoteur : SAHEBMenouar Pr (Université Larbi Ben Mhidi, Oum El-Bouaghi). Examinateurs: ABABSA Labed Pr (Université Larbi Ben Mhidi, Oum El-Bouaghi). Examinateurs: HOUHAMDI Moussa Pr (Université de Guelma). Examinateurs: OUAKID Mohamed Laid Pr (Université d’Annaba). Année universitaire: 2018-2019 << ِ ِ أَﻟَْﻢ ﺗَ َﺮ أَ ﱠن ﱠاﻪﻠﻟَ ﻳُﺴَﺒِّ ُﺢ ﻟَﻪُ ﻣَ ْﻦ ﻓﻲ اﻟﺴﱠﻤَ َﺎوات َو ْاﻷَ ْر ِض َواﻟﻄﱠْﻴ ُﺮ ٍ ۖ◌ ِ ِ ۗ◌ ِ ِ ﺻَ ﺎ ﻓ ـﱠ ﺎ ت ُﻛ ﻞﱞ ﻗَ ْﺪ ﻋَ ﻠ ﻢَ ﺻَ َﻼ ﺗَ ﻪُ َو ﺗَ ْﺴ ﺒ ﻴ ﺤَ ﻪُ َو ﱠاﻪﻠﻟُ ﻋَﻠﻴﻢٌ ﺑﻤَﺎ ﻳَﻔْ َﻌﻠُ َﻮن >> ﺳﻮرة اﻟﻨﻮراﻷﻳﺔ 41 Dédicaces Je dédie ce travail à : A mes parents qui m’ont tout donné, et qui étaient toujours la à coté de moi dans chaque pats depuis le premier crie pour m’aidé, m’orienté avec leurs amour et leurs sacrifices, malgré les couts dures de la vie. Aucun hommage ne pourrait être à la hauteur de l’amour Dont ils ne cessent de me combler. -

Small Grants for Building Research Capacity Among Tanzanian and Kenyan Students

CEPF FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT I. BASIC DATA Organization Legal Name: BirdLife International Project Title (as stated in the grant agreement): Small Grants for Building Research Capacity among Tanzanian and Kenyan Students Implementation Partners for this Project: BirdLife International – African Partnership Secretariat, Nature Kenya, Wildlife Conservation Society of Tanzania Project Dates (as stated in the grant agreement): September 1, 2006 - June 30, 2009 Date of Report (month/year): 31 July 2009 II. OPENING REMARKS Provide any opening remarks that may assist in the review of this report. Acceleration in environmental and habitat degradation, habitat and biodiversity loss, over-exploitation of resources and loss of species are some of the threats facing biodiversity conservation. Concerted efforts are being put in place to overcome these threats through: site protection, site management, invasive species control, species recovery, captive breeding, reintroduction, national legislation, habitat restoration, habitat protection and awareness-raising and communication. However, lack of sufficient biological knowledge, shortfalls in funding, and lack of sufficient capacity still pose a major challenge. This project was developed to fill gaps in biological knowledge while at the same time developing the capacity of a cadre of research scientists. When the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) launched its 5-year conservation programme in the Eastern Arc Mountains and Coastal Forests of Kenya and Tanzania (EACF), the focus was to address most of these thematic areas. These included improving biological knowledge in the hotspot through research, monitoring, education and awareness raising, integrating and engaging local populations into biodiversity conservation and livelihood initiatives and building the capacity through small scale efforts to increase biological knowledge of the sites and efforts to conserve Critically Endangered Species in the hotspot and connectivity of biologically important patches. -

The Avifauna of Two Woodlands in Southeast Tanzania

Scopus 25: 2336, December 2005 The avifauna of two woodlands in southeast Tanzania Anders P. Tøttrup, Flemming P. Jensen and Kim D. Christensen In Tanzania Brachystegia or miombo woodland occupies about two-thirds of the country including the central plateau to the north and the south eastern plateau (Lind & Morrison 1974). Along the coast more luxuriant woodlands are found in what White (1983) terms the Zanzibar-Inhambane regional mosaic floristic region. This highly complex vegetation comprises unique types of forest, thicket, woodland, bushland and grassland, interspersed with areas presently under cultivation and fallow (Hawthorne 1993). The coastal woodlands are usually deciduous or semi-deciduous but contain some evergreen species and often merge with coastal thickets, scrub forest and coastal forest (Hawthorne 1993, Vollesen 1994). The avifauna of miombo woodlands has been described for Zambia (e.g. Benson & Irwin 1966) and Zimbabwe (e.g. Vernon 1968, 1984, 1985), while little has been published on the birds of the coastal woodlands. An exception is Stjernstedt (1970) who reported on the birds in lush and dense Brachystegia microphylla vegetation in a sea of miombo in southeast Tanzania. Here we report our observations of birds in two woodlands in coastal southeast Tanzania, one of which harboured miombo trees. We present information on the number of species encountered during the fieldwork, and compare the avifauna of the two sites. We discuss possible causes for the differences observed and provide new information on habitat preferences for some of the species we recorded at these sites. Study sites Field work was carried out in two coastal woodlands in the Lindi Region, southeast Tanzania in September and October 2001. -

Zambia and Zimbabwe 28 �Ovember – 6 December 2009

Zambia and Zimbabwe 28 ovember – 6 December 2009 Guide: Josh Engel A Tropical Birding Custom Tour All photos taken by the guide on this tour. The Smoke that Thunders: looking down one end of the mile-long Victoria Falls. ITRODUCTIO We began this tour by seeing one of Africa’s most beautiful and sought after birds: African Pitta . After that, the rest was just details. But not really, considering we tacked on 260 more birds and loads of great mammals. We saw Zambia’s only endemic bird, Chaplin’s Barbet , as well as a number of miombo and broad-leaf specialties, including Miombo Rock-Thrush, Racket-tailed Roller, Southern Hyliota, Miombo Pied Barbet, Miombo Glossy Starling, Bradfield’s Hornbill, Pennant-winged ightjar, and Three-banded Courser. With the onset of the rainy season just before the tour, the entire area was beautifully green and was inundated with migrants, so we were able to rack up a great list of cuckoos and other migrants, including incredible looks at a male Kurrichane Buttonquail . Yet the Zambezi had not begun to rise, so Rock Pratincole still populated the river’s rocks, African Skimmer its sandbars, and Lesser Jacana and Allen’s Gallinule its grassy margins. Mammals are always a highlight of any Africa tour: this trip’s undoubted star was a leopard , while a very cooperative serval was also superb. Victoria Falls was incredible, as usual. We had no problems in Zimbabwe whatsoever, and our lodge there on the shores of the Zambezi River was absolutely stunning. The weather was perfect throughout the tour, with clouds often keeping the temperature down and occasional rains keeping bird activity high. -

ETHIOPIA: Birding the Roof of Africa; with Southern Extension a Tropical Birding Set Departure

ETHIOPIA: Birding the Roof of Africa; with Southern Extension A Tropical Birding Set Departure February 7 – March 1, 2010 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos taken by Ken Behrens during this trip ORIENTATION I have chosen to use a different format for this trip report. First, comes a general introduction to Ethiopia. The text of this section is largely drawn from the recently published Birding Ethiopia, authored by Keith Barnes, Christian, Boix and I. For more information on the book, check out http://www.lynxeds.com/product/birding-ethiopia. After the country introduction comes a summary of the highlights of this tour. Next comes a day-by-day itinerary. Finally, there is an annotated bird list and a mammal list. ETHIOPIA INTRODUCTION Many people imagine Ethiopia as a flat, famine- ridden desert, but this is far from the case. Ethiopia is remarkably diverse, and unexpectedly lush. This is the ʻroof of Africaʼ, holding the continentʼs largest and most contiguous mountain ranges, and some of its tallest peaks. Cleaving the mountains is the Great Rift Valley, which is dotted with beautiful lakes. Towards the borders of the country lie stretches of dry scrub that are more like the desert most people imagine. But even in this arid savanna, diversity is high, and the desert explodes into verdure during the rainy season. The diversity of Ethiopiaʼs landscapes supports a parallel diversity of birds and other wildlife, and although birds are the focus of our tour, there is much more to the country. Ethiopia is the only country in Africa that was never systematically colonized, and Rueppell’s Robin-Chat, a bird of the Ethiopian mountains. -

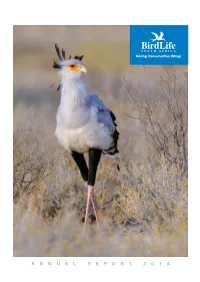

A N N U a L R E P O R T 2 0

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 CONTENTS Chairman’s Message – 1 – Chief Executive Officer’s Report – 2 – Challenges in 2014 – 6 – Awards – 7 – Conserving Terrestrial Birds – 8 – Encouraging Ecological Sustainability – 10 – Saving Seabirds – 11 – Protecting Sites And Habitats – 13 – Birds And People – 15 – Sponsors And Supporters – 20 – Financials – 21 – Albert Froneman Cover page: Albert Froneman ANNUAL REPORT 2014 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE Albert Froneman When BirdLife South Africa’s current Chief Today we are ready for more change. Executive Officer took up his position over six years ago it was like watching new It is time for a subtle shift, a stretch of leaves stretch out from all the trees. It was great wings perhaps, an energetic reach a very ‘green time’. Barn Swallows arrived up to a higher place, to the tips of where on the horizon, and the days widened like the sun comes onto the land, to the big flowers. gathering rows of summer swallows: the governance structure and the membership For many of us there is something structure of BirdLife South Africa must unsettling about change. But if we care As with all good ideas and actions, timing now realign with an even more efficient to look at Nature; if we pick up the is important. Change must therefore be way of doing things, a way that will profit rhythms and listen carefully, we will hear coordinated; it must be sequential. And from greater influence within the world the beautiful (and magnificent) tick of the birdwatchers – like us – appreciate this, of environmental conservation, a way circadian clock.