The Quaker Meeting House in York 1673 – 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castlegate, York: Audience Research Pilot

CASTLEGATE, YORK: AUDIENCE RESEARCH PILOT PROJECT GEORGIOS ALEXOPOULOS INSTITUTE FOR THE PUBLIC UNDERSTANDING OF THE PAST, UNIVERSITY OF YORK APRIL 2010 1 Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................3 List of figures.................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................5 1.1 Objectives ............................................................................................................5 1.2 Methodology........................................................................................................5 1.3 Potential for fulfilling long term objectives.........................................................6 2. Audience survey demographics.................................................................................6 2.1 Gender..................................................................................................................6 2.2 Age distribution ...................................................................................................7 2.3 Origin of respondents ..........................................................................................8 2.4 Educational background ......................................................................................8 2.5 Occupations .........................................................................................................9 -

Creating the Slum: Representations of Poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate Districts of York, 1875-1914

Laura Harrison Ex Historia 61 Laura Harrison1 University of Leeds Creating the slum: representations of poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate districts of York, 1875-1914 In his first social survey of York, B. Seebohm Rowntree described the Walmgate and Hungate areas as ‘the largest poor district in the city’ comprising ‘some typical slum areas’.2 The York Medical Officer of Health condemned the small and fetid yards and alleyways that branched off the main Walmgate thoroughfare in his 1914 report, noting that ‘there are no amenities; it is an absolute slum’.3 Newspapers regularly denounced the behaviour of the area’s residents; reporting on notorious individuals and particular neighbourhoods, and in an 1892 report to the Watch Committee the Chief Constable put the case for more police officers on the account of Walmgate becoming increasingly ‘difficult to manage’.4 James Cave recalled when he was a child the police would only enter Hungate ‘in twos and threes’.5 The Hungate and Walmgate districts were the focus of social surveys and reports, they featured in complaints by sanitary inspectors and the police, and residents were prominent in court and newspaper reports. The area was repeatedly characterised as a slum, and its inhabitants as existing on the edge of acceptable living conditions and behaviour. Condemned as sanitary abominations, observers made explicit connections between the physical condition of these spaces and the moral behaviour of their 1 Laura ([email protected]) is a doctoral candidate at the University of Leeds, and recently submitted her thesis ‘Negotiating the meanings of space: leisure, courtship and the young working class of York, c.1880-1920’. -

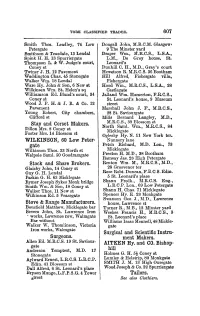

Stay and Corset Makers. WILKINSON, 60 Low Peter- Gate Stock And

YORK CLASSIFIED TRADES. 607 Smith Thos. Leadley, 74 Low Dougall John, M.B.C.M. Glasgow' Petergate 9 The Minster yard Smithson & Teasdale, 13 Lendal Draper Wm., M.R.C.S., L.S.A., Spink H. H. 13 Spurriergate L.M., De Grey house, St. Thompson L. & W, Judge's court, Leonard's Coney st Dunhill C. H., M.D., Gray's court Twiner J. H. 12 Pavement Hewetson R M.RC.S. 36 Bootham Waddington Chas. 45 Stonegate Hill Alfred, Fishergate villa, Walker Wm. 18 Lendal Fishergate Ware Hy. John & Son, 6 New st Hood Wm., M.R.C.S., L.S.A., 28 Wilkinsen Wm. St. Helen's sq Castlegate Williamson Ed. Bland's court, 34 Jalland Wm. Hamerton, F.R.C.S., Coney st St. Leonard's house, 9 Museum Wood J. P. H. & J. R. & Co. 12 street Pavement Marshall John J. F., M.R.C.S., Young Robert, City chambers, 28 St. Saviourgate Clifford st Mills Bernard Langley, M.D., M.RO.S., 39 Blossom st Stay and Corset Makers. North Sam!. Wm., M.R.C.S., 84 Dillon Mrs. 8 Coney st Micklegate Foster Mrs. 14 Blossom st Oglesby Hy. N. 11 New York ter. WILKINSON, 60 Low Peter- Nunnery lane gate Petch Richard, M.D. Lon., 73 Wilkinson Thos. 33 North st Micklegate Walpole Sam!. 50 Goodramgate Preston H. M.D., 38 Bootham Ramsay Jas. 23 High Petergate Stock and Share Brokers. Renton Wm. M., M.R.C.S., M.D., Glaisby John, 14 Coney st 28 Grosvenor ter Guy G. H. Lendal Rose Robt. -

Castle Piccadilly Conservation Area Appraisal 2006

rd Approved 23 March 2006 CONTENTS Preface Conservation Areas and Conservation Area Appraisals Introduction The Castle Piccadilly Conservation Area Appraisal 1. Location 1.1 Location and land uses within the area 1.2 The area’s location within the Central Historic Core Conservation Area 2. The Historical Development of the Area 2.1 The York Castle Area 2.2 The Walmgate Area 2.3 The River Foss 2.4 The Castlegate Area 3. The Special Architectural and Historic Characteristics of the Area 3.1 The York Castle Area 3.2 The Walmgate Area 3.3 The Castlegate Area 4. The Quality of Open Spaces and Natural Spaces within the Area 4.1 The River Foss 4.2 The York Castle Area 4.3 Tower Gardens 4.4 Other Areas 5. The Archaeological Significance of the Area 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Evidence from Archaeological Investigations 6. Relationships between different areas covered within the Appraisal 6.1 Views from within the area covered by the Appraisal 6.2 Views into the area covered by the Appraisal 6.3 The relative importance of the different parts of the area covered by this appraisal Conclusion Appendix 1. Listed Buildings within the Appraisal area CASTLE PICCADILLY CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1 PREFACE INTRODUCTION CONSERVATION AREAS AND THE CASTLE PICCADILLY CONSERVATION AREA CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL APPRAISALS This appraisal was approved by the City of York The legal definition of conservation areas as stated Council Planning Committee on 23rd March 2006 in Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings as an accompanying technical document to the and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 is: Castle Piccadilly Development Brief 2006, which is also produced by the City of York Council. -

1-3 CLIFFORD STREET York, YO1 9RG

RESTAURANT UNIT TO LET 1-3 CLIFFORD STREET York, YO1 9RG Key Highlights • New lease available • Nearby operators include Nando’s, Yates and Pizza Hut • Former Prezzo Restaurant unit to let • GIA: 567 sq m (6,104 sq ft) • Situated in close proximity to York City Centre • Midnight premises license • 140 covers arranged over ground and first floors SAVILLS LONDON 33 Margaret Street London W1G 0JD +44 (0) 20 7409 8178 savills.co.uk York Location The basement is accessed by an internal staircase to the rear and comprises customer toilets, trade kitchen, staff The premises is located on a prominent corner plot at the toilets, beer cellar and ancillary storage. crossroads between Coppergate, King Street, Castlegate and the busy Clifford Street (B1227), just 100 metres east of The first floor comprises an additional trade areaExperian with Goad Plan Created: 26/03/2021 the River Ouse. The restaurant is situated fronting Clifford seating 50provided metres on loose tables and chairs for a further Created By: Savills Street, opposite Subway. For more information on our products and services: 70 Copyrightcovers. and confidentiality To the Experian, rear 2020. is© Crown a small food preparation area and www.experian.co.uk/goad | [email protected] | 0845 601 copyright and database rights 2020. OS 100019885 two customer toilets. 6011 York benefits from an extensive leisure offering including operators such as JD Wetherspoon, Greene King, Nando’s, The second floor comprises a staff room, office, meeting The Botanist, Pizza Express, Wagamama, McDonalds and room, staff toilet and ancillary storage. Five Guys. Coppergate Shopping Centre is located just 50 metres to the east of the property and offers further food The premises has the following approximate gross internal and drink options including Caffé Nero, Scoops and Café 21. -

UNIQUE FREEHOLD OPPORTUNITY for SALE Potential for Alternative Use Subject to Planning Shipton Road

22 LENDAL YORK, YO1 8DA UNIQUE FREEHOLD OPPORTUNITY FOR SALE Potential for alternative use subject to planning Shipton Road Wigginton Road Wigginton Malton Road Clifton Haxby Road Stockton Lane Burton Stone Lane Water End Penley’s Grove Street Hewarth Road DARLINGTON SCARBOROUGH A19 A1036 (A1M) RIVER FOSS (A64) Bootham St John St Gillygate Monkgate Tang Hall Lane Jewbury James Street Foss Bank Low Petergate Layerthorpe Foss Islands Road Melrosegate RIVER OUSE Stonegate Leeman Road 24 MILES TO Station Road LEEDS Fossgate Peasholme Green Piccadilly A1036 Navigation Road Castlegate HARROGATE Walmgate YORK RAILWAY Micklegate LOCATION Tower St STATION Skeldergate St Deny’s Road York is an internationally renowned tourist A59 destination and an attractive, historic A1036 cathedralA1079 city. It is located approximatelyHULL 1 HR & 50 MINS TO Hull Road Paragon Street LONDON VIA TRAIN Kent St 200 miles north of London, 24 miles Blossom Street Fishergate north-east of Leeds and 85 miles south Heslingtonof Newcastle. Road There are regular train A59 services to London that take under 1 hour and 50 minutes. Scarcroft Road LEEDS (A64) The retail market in York remains one A1036 of the strongest in the country. Latest research estimate 6.9 million visitors to VISITORS SPEND Barbican Road York per year, spending in the region of £564 million. York is home to a major £564 MILLION PER YEAR Albemarle Road university and benefits from a catchment A19 population of approximately 488,000 of Knavesmire Road Bishopthorpe Road which 294,000 regard York as their main shopping destination. York benefits from great variety with the prime trading areas of Coney Street, Davygate, High Ousegate and Parliament Street complementing the tourist streets of 6.9M VISITORS Stonegate, Low Petergate and The Shambles. -

York, 5 Museum Street

TO LET REFURBISHED GRADE A OFFICE ACCOMMODATION MUSEUM STREET YORK, YO1 7DT + Open plan + Fully air-conditioned / heated + Car Parking Available MUSEUM STREET YORK, YO1 7DT LOCATION The property is within easy walking distance of York’s main line railway station with a regular service to London Kings Cross (fastest journey time approximately 1 hour 50 minutes). The premises are close York’s retail, leisure and HELMSLEY cultural amenities including York Minster with B1363 views over Museum Gardens. York has an estimated LORD MAYORS WALK THIRSK population of 207,000 persons and a primary A19 BOOTHAM catchment of approximately 488,000 persons. GATE Park & Ride Y MONKGATE GILL 1 Railway Station ST LEONARDS HIGH PETERGATE2 JEWBUR DEANGATE 2 York Minster 8 GOODRAMGATE MARYGATE LOW PE 3 Museum Gardens 3 MUSEUM STREET TER G A 3 T 7 E 4 National Railway Museum River Ouse LENDAL D 4 MUSEUM STREET AVYGATE COLLIERGA STONEGATE 5 Cliffords Tower SHAMBLES HARROGATE PARLIAMENT STREET PEASH ST SAVIOURGATE A59 LEEMAN ROAD CONEY STREET2 TE LENDAL BRIDGE 1 STONEBOW 6 Jorvik Viking Centre GEORGE HUDSON ST NORTH STREET FOSSGATE 1 4 PAVEMENT 7 Main Retail Centre 6 CLIFFORD STREET PICCADILLY CASTLEGATE 8 York Theatre Royal OUSE BRIDGE River Ouse SKELDERGATE STATION ROAD 1 The Ivy MICKLEGATE 5 PICCADILLY 2 Bettys NUNNERY LANE 3 The Star Inn the City Park & Ride BLOSSOM STREET SKELDERGATE BRIDGE 4 The Grand Hotel LEEDS A64 / A1 MUSEUM STREET YORK, YO1 7DT SPECIFICATION + Fully refurbished Grade A offices + Open plan + Private entranceway + Fully air-conditioned/heated + Kitchen facilities + Access control + Male & Female WC + Fully carpeted throughout + On site car parking available (further details available upon request) STAIRS STAIRS FEMALE MALE WC WC First Floor 2,200 sq ft WC LOBBY LANDING Second Floor 870 sq ft LOBBY LOBBY LOBBY TOTAL 3,070 sq ft FIRST FLOOR SECOND FLOOR MUSEUM STREET YORK, YO1 7DT FURTHER INFORMATION The premises Grade A self-contained offices over two floors which VIEWING can be taken as a whole or part let. -

St Mary Bishophill Junior and St Mary Castlegate L

The Archaeology of York Anglo-Scandinavian York 8/2 St Mary Bishophill Junior and St Mary Castlegate L. P. Wenham, R. A. Hall, C. M. Briden and D. A. Stocker Published for the York Archaeological Trust 1987 by the Council for British Archaeology The Archaeology of York Volume 8: Anglo-Scandinavian York General Editor P.V. Addyman Co-ordinating Editor V. E Black ©York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research 1987 First published by Council for British Archaeology ISBN 0 906780 68 3 Cover illustration: St Mary Bishophill Junior, opening in east elevation of belfry. Drawing by Terry Finnemore Digital edition produced by Lesley Collett, 2011 Volume 8 Fascicule 2 St Mary Bishophill Junior and St Mary Castlegate By L. P. Wenham, R. A. Hall, C. M. Briden and D. A. Stocker Contents St Mary Bishophill Junior ........................................................................................74 Excavation to the North of the Church by L. P. Wenham and R. A. Hall. ..................................................................................75 Introduction ............................................................................................................75 The excavated sequence ..........................................................................................76 Conclusions ............................................................................................................81 The Tower of the Church of St Mary Bishophill Junior by C. M. Briden and D. A. Stocker. .............................................................................84 -

Coppergate, York: Audience Research Pilot

COPPERGATE, YORK: AUDIENCE RESEARCH PILOT PROJECT GEORGIOS ALEXOPOULOS INSTITUTE FOR THE PUBLIC UNDERSTANDING OF THE PAST, UNIVERSITY OF YORK NOVEMBER 2009 Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................3 Introduction ...................................................................................................................3 Objectives ..................................................................................................................3 Methodology..............................................................................................................4 Potential for fulfilling long term objectives...............................................................4 1. Audience survey demographics.................................................................................5 1.1 Gender..................................................................................................................5 1.2 Age distribution ...................................................................................................5 1.3 Origin of respondents ..........................................................................................6 1.4 Educational background ......................................................................................7 1.5 Occupations .........................................................................................................7 1.6 Ethnicity...............................................................................................................8 -

York Civic Trust Response to York Castle Gateway Open Brief

York Civic Trust response to York Castle Gateway Open Brief Overall, York Civic Trust welcomes the draft Brief as a positive statement of intent. It is well considered and draws extensively on the public engagement exercises that have been undertaken. It considers the site(s) from a range of issues: access, heritage, commercial, playfulness, movement, green space, views, etc. – and benefits from this broad approach. We particularly are supportive of the broad range of perspectives that the brief brings to the site, linking the past and the future. In particular, the focus on individual and personal narratives for discussing the significance of the area both historically and in the present. Before offering specific and thematically arranged comments that are offered as reflections on the Brief, the Trust suggests more guidance might be given in the Brief as way of a ‘hierarchy’ or ‘priorities’ of what is required for the site(s). The budget, let alone the complex spatial and conservation restrictions of the site(s), will likely restrict the ability to satisfy all proposed aspects of the Brief; compromises must be expected. Such a hierarchy may help successful designs come to fruition, as well as help to channel realistic public expectations. We think this is important – not to restrict creativity but as a way of assisting in helping to concentrate this creativity for the greatest impact. Open brief for the Whole Area One of the elements of this site that is so appealing is that for the first time ever the site can be considered as whole, and we can celebrate the open nature of the site. -

Textile Production at 16–22 Coppergate

The Archaeology of York The Small Finds 17/11 Textile Production at 16–22 Coppergate By Penelope Walton Rogers Textile Production at 16-22 Coppergate By Penelope Walton Rogers Published for the York Archaeological Trust 1997 by the Council for British Archaeology Contents Introduction....................................................................................................... 1687 The.excavation.at.16-22.Coppergate.by R.A. Hall .........................................1689 The.range.and.quality.of.the.evidence............................................................. 1708. Significance.of.the.collection........................................................................... 1709. The.Processes.of.Textile.Production..................................................................... 1711 Raw.materials.with a contribution by H. K. Kenward ............................................1712 Fibre.preparation........................................................................................... 1719 Spinning........................................................................................................ 1731 Yarn.winding.and.warping.............................................................................. 1749 Weaving......................................................................................................... 1749 Dyes.and.dyeing.with a contribution by A.R. Hall ..........................................1766 Finishing.wool.cloth.with a contribution by A.R. Hall ......................................1771 -

Bibliography of Stained Glass in York City Churches (Excluding York Minster)

Bibliography of Stained Glass in York City Churches (excluding York Minster) General Manuscript Sources Cambridge, Trinity College MS 0. 4. 33: H. Keep, Monumenta Eboracensia, 1681 London, Victoria & Albert Museum, National Art Library, MSS 86. BB. 50–51: J. W. Knowles, Stained Glass in the York Churches, 2 vols, c. 1890–1920 Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Top. Yorks. C. 14: Henry Johnston, 1669–70 York, City Reference Library, MS Y040 1935. 9. J. W. Knowles, York Churches, c. 1890- 1920 York, King’s Manor Library, University of York: Peter Newton Archive York, King’s Manor Library, University of York: photograph and slide collections York, York Minster Library, MS L1 (8): James Torre, Antiquities Ecclesiastical of the City of York, c. 1691 Published Sources M. D. Anderson, The Imagery of British Churches, London, 1955 —, Drama and Imagery in English Medieval Churches, Cambridge, 1963 H. Arnold and L. B. Saint, Stained Glass of the Middle Ages in England and France, London 1913 [esp. chps 10 ‘Fourteenth-Century Glass at York’ and 15 ‘Fifteenth Century Glass at York’] A. Barclay, Views of the Parish Churches in York, with a Short Account of Each, York, 1831 C. M. Barnett, ‘Commemoration in the Parish Church: Identity and Social Class in Late Medieval York’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, lxxii, 2000, pp. 73–92 —, ‘Memorials and Commemoration in the Parish Churches of Late Medieval York’, PhD thesis, University of York, 1997 J. N. Bartlett, ‘The Expansion and Decline of York in the Later Middle Ages’, Economic History Review, 12, 1959–60, pp. 17–33 P. Barnham, C. Cross and A.