Draft Revised Recovery Plan for the N'n' Or Hawaiian Goose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alien Animals in Hawaii's Native Ecosystems: Toward Controlling The

ALIEN ANIMALS IN HAWAI!IfS NATIVE ECOSYSTEMS: TOWARD CONTROLLING THE ADVERSE EFFECTS OF INTRODUCED VERTEBRATES Charles P. Stone ABSTRACT The adverse effects of introduced birds and mam- mals on native taxa and ecosystems in Hawaifi have been long term, widespread, and severe. Impacts began at least 1,500 years ago with colonization by the Poly- nesians and their flora and fauna, and continued with their increasingly severe disturbance to the landscape, especially below 500 m elevation. Problems accelerated with the arrival of continental man in 1778, and con- tinue to the present day with suspected deliberate re- leases of birds that threaten native species as re- cently as 1982. Alien vertebrates can affect native biota through predation, competition, depredation, and habitat degradation. Negative impacts can be subtle or dramatic, but evidence of importance is manifested in large percentages of extinct and rare taxa. In this paper, adverse effects of major bird and mammal intro- ductions are outlined where possible for islands, vege- tation zones, and rare taxa. Although much remains to be learned, suggestions for reducing negative effects of alien vertebrates can be made. These include: En- forcement of efficient quarantine procedures; suffi- cient support for enduring and complete vertebrate dam- age control programs (including research, management, and monitoring) on lands managed for preservation of native Hawaiian ecosystems and taxa; development of multiple and adaptable methods of vertebrate damage reduction; preservation and management of the most in- tact areas remaining in Hawai'i; and cooperation and communication among the agencies and special interest groups (including developers and conservationists) in land use planning on regional bases. -

December 2011

Volume 22, Number 6 December 2011 Price: $5.00 This Little Piggy… Hawai‘i’s Imperiled Species Receive t may star in GEICO commercials and be National Attention at Wildlife Convention Ifeatured in children’s nursery rhymes, but in Hawai‘i’s forests, there’s nothing ast month, The Wildlife Society, a cent watershed initiative. “We have to con- funny or cute about Sus scrofa, the wild pig Lnational association made up mostly of trol ungulates. Fencing and removal of ungu- that does more damage to Hawai‘i’s native specialists in the area of wildlife research lates, especially in watersheds, is a major part ecosystems than any other animal in the and management, held its annual conven- of our plan going forward,” Aila said. “We islands. tion at the Waikoloa resort, on the Big have made a conscious decision that in prior- And if anyone harbored doubts about it, Island. ity watersheds, we are going to double the they only had to sit through a few of the Over the four days of discussions and amount of fencing and protection.” many presentations at the recent symposia connected with the meeting, some Fencing, removal of introduced game convention of The Wildlife Society, held of the most respected names in Hawai‘i species, and restoration of habitat for native last month on the Big Island. Pigs directly biology took to the lectern, providing a largely wildlife was an undercurrent in nearly all of tear up trees and the forest floor. They mainland audience with their perspectives on the talks by Hawai‘i presenters. -

Hawaii National Parte NATURE NOTES

Hawaii National Parte NATURE NOTES V N o v L M U B M E E Q T T H M E E E E 1933 */£•£>. DEPAMMBNT 0F/Tlffi;lltol9Bgj OFFIC^OF NATIONAL PARKS^? HJIllffNGS,1 ANL RESERVATl6N£f 101W "'"*/?< 'HAWAII NATIONAL PARK V/f< NATURE NOTES f£j. Volume III May - Junfe, 1953 sNumber 2 Nature Notes from Hawaii National Park is % bimonthly pamphlej;N edited by the Park Naturalist, and distributed to those inJereswoT^^the 1 natural features of the park. Free copies may be oMained,^jointhe I office of the Park Naturalist, address, Hawaii National Pa^fc IlajTaii. Anyone desiring to use or publish articles appearing in Naiarre^'Notes may do so. Please give credit to the author end pamphlet. #J%i{$i\. E. G. Wine-ate, Superintendent John E. DaerirJ/Jr, Park Naturalist TABLE OF CONTENTSy |W Nene - The Hawaiian Goose $/ ffl AW ' by John iS. Doorr, Jr. Rocks in Hawaii National'Park - Volcanic Glass, A Common Rock yd^y^y J°hn E. Doerr, Jr. Credit for the diagrarnii^h'pages 23,25,27, and 37 is due S& /V Nancy Elliott Poerr -23- nEnEr THE tnutourtN GOOS£r Introduction. Hawaii has seldom if ever experienced seeing the famous flying-wedge' formation of a flock of geese.. The "honk- honk-k'wonk" of the" Canada Goose migrating southward across a fall sky or northward*with the spring is not heard in Hav7aii.(l) Perhaps - centuries ago - the "honk-honk-k'wbnk" of geese did announce the fall arrival and the spring departure of feathered visitors along the shores of the islands. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Anserini (Swans and True Geese) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Anserini (Swans and True Geese)" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Tribe Anserini (Swans and True Geese) MAP 10. Breeding (hatching) and wintering (stippling) distributions of the mute swan, excluding introduced populations. Drawing on preceding page: Trumpeter Swan brownish feathers which diminish with age (except MuteSwan in the Polish swan, which has a white juvenile Cygnus alar (Cmelin) 1789 plumage), and the knob over the bill remains small through the second year of life. Other vernacular names. White swan, Polish swan; In the field, mute swans may be readily iden Hockerschwan (German); cygne muet (French); tified by their knobbed bill; their heavy neck, usu cisne mudo (Spanish). ally held in graceful curve; and their trait of swim ming with the inner wing feathers raised, especially Subspecies and range. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Index Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Index" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Index The following index is limited to the species of Anatidae; species of other bird families are not indexed, nor are subspecies included. However, vernacular names applied to certain subspecies that sometimes are considered full species are included, as are some generic names that are not utilized in this book but which are still sometimes applied to par ticular species or species groups. Complete indexing is limited to the entries that correspond to the vernacular names utilized in this book; in these cases the primary species account is indicated in italics. Other vernacular or scientific names are indexed to the section of the principal account only. Abyssinian blue-winged goose. See atratus, Cygnus, 31 Bernier teal. See Madagascan teal blue-winged goose atricapilla, Heteronetta, 365 bewickii, Cygnus, 44 acuta, Anas, 233 aucklandica, Anas, 214 Bewick swan, 38, 43, 44-47; PI. -

Hawai'i Bird Coloring Book

Forest Friends Kupuna (our elders) teach us that we are all ‘ohana (family) -- trees of the forest, plants of the seashore, and all critters that live on our islands, including us humans. And as humans, we have a responsibility to care for our ‘ohana. Hawai‘i’s location in the middle of the ocean makes our plants and animals more special. Each one evolved to uniquely adapt to its environment and created microenvironments on which other species depend. This interdependence between species and their small area of habitat makes them vulnerable. Some of our native plants and animals need more help from us humans than others. Many are endangered or have disappeared in recent times What are native plants and animals you ask? Well, natives are species that live in a specific area without the help of humans. They started existence a really long time ago, maybe thousands or millions of years ago and became unique to a specific place. in Hawai‘i, most got here by wind or wave before the ancient Polynesians arrived in their voyaging canoes. There are two kinds of native species: endemic and indigenous. Endemic species are found only in one place in the world. They could live on all our islands or in only one valley on one of our islands and adapted to living only in one isolated location, like our islands. Endemic species are unique to one place. Indigenous species are found in more places throughout the world but have adapted special characteristics for each location they find themselves in. They are more adaptable and can live in a variety of places at the same time. -

Nēnē Or Hawaiian Goose (Branta Sandvicensis)

Nēnē or Hawaiian Goose (Branta sandvicensis) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawaii 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: Nēnē or Hawaiian Goose (Branta sandvicensis) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION.......................................................................................... 3 1.1 Reviewers....................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review:................................................................. 3 1.3 Background: .................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS....................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy......................... 4 2.2 Recovery Criteria.......................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 7 2.4 Synthesis....................................................................................................................... 12 3.0 RESULTS ........................................................................................................................ 12 3.1 Recommended Classification:................................................................................... -

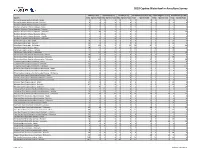

2020 Captive Waterfowl in Aviculture Survey

2020 Captive Waterfowl in Aviculture Survey Global (n=324) Australasia (n=3) Canada (n=12) Continental Europe (n=76) United Kingdom (n=51) United States (n=182) Species Total Species Total Total Species Total Total Species Total Total Species Total Total Species Total Total Species Total Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta - Males 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta - Females 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta - Unknowns 8 9 8 8 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 Southern Screamer Chauna torquata - Males 50 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 45 0 Southern Screamer Chauna torquata - Females 35 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 32 0 Southern Screamer Chauna torquata - Unknowns 1 86 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 1 78 Northern Screamer Chauna chavaria - Males 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Northern Screamer Chauna chavaria - Females 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Northern Screamer Chauna chavaria - Unknowns 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Mute Swan Cygnus olor - Males 38 0 0 0 4 0 8 0 2 0 22 0 Mute Swan Cygnus olor - Females 38 0 0 0 4 0 8 0 2 0 21 0 Mute Swan Cygnus olor - Unknowns 26 102 0 0 5 13 20 36 0 4 1 44 Black Swan Cygnus atratus - Males 94 0 2 0 5 0 20 0 19 0 46 0 Black Swan Cygnus atratus - Females 97 0 2 0 7 0 19 0 20 0 48 0 Black Swan Cygnus atratus - Unknowns 55 246 8 12 0 12 31 70 12 51 4 98 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus - Males 46 0 0 0 0 0 6 0 9 0 30 0 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus - Females 50 0 0 0 0 0 8 0 8 0 33 0 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus - Unknowns 6 102 0 0 0 0 3 17 0 17 3 66 Trumpeter Swan Cygnus buccinator - Males 37 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 3 0 33 -

Prehistoric Decline of Genetic Diversity in the Nene

B REVIA bon chronology (Fig. 1A) suggests that the nene’s EVOLUTION loss of genetic variability took place during a period of prehistoric human population growth Prehistoric Decline of Genetic (900 to 350 years ago), when settlements expand- ed into marginal ecological zones (7). Radiocar- bon dates (1, 5, 8) indicate that the extirpation of Diversity in the Nene the nene on Kauai and the extinction of at least Ellen E. Paxinos,1* Helen F. James,2 Storrs L. Olson,2 five of the nine large ground-dwelling Hawaiian birds (1) occurred during this time period. Eco- Jonathan D. Ballou,1 Jennifer A. Leonard,3 Robert C. Fleischer1,2† logical changes associated with human settlement are assumed to have caused the extinctions (1) The nene (or Hawaiian goose, Branta sandvicen- generations (about 600 years) suggest that the and apparently caused a dramatic reduction in sis) once occurred on most of the main Hawaiian most likely explanation is a prehistoric population genetic diversity in the nene on Hawaii as well. Islands (1), but by Captain Cook’s arrival in 1778, bottleneck (6). A reduction of H from 0.80 to 0.26 Ultimately, we must ask why the nene popu- nene were found only on the island of Hawaii (2). in populations of varying size (500 to 10,000) can lation on Hawaii could escape prehistoric extinc- A decline that began in the 1800s reduced the only occur if the populations decline to fewer than tion while many other Hawaiian birds did not. nene population to fewer than 30 individuals by 270 females (for a rate of decline of r ϭϪ0.01) Cultural changes may have created better condi- the middle of the 20th century (2). -

1964-65 Federal Duck Stamp Design Contest Won By

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR *********************news release FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Most - 343-5634 For Release DECEMBER10, 1963 1964-65 FEDERALDUCK STAMP DESIGN CONTEST WON BY MARYLANDARTIST A watercolor drawing showing a pair of Nene geese on the volcanic slopes of Hawaii will be the design for the 1964-65 Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp, the Department of the Interior announced today. Stanley Stearns of Stevensville, Maryland, drew the winning design which was selected today from among 158 entries. Stearns also drew the design for the 1955-56 stamp. A total of 8'7 artists entered this 15th annual Federal "Duck Stamp" contest which is conducted in Washington, D. C., by the Fish and Wildlife Service. Second and third places in the contest went to Leslie C. Kouba of Minneapolis, Minnesota. His two drawings featured old squaw ducks and emperor geese. The Nene goose (pronounced "nay-nay“), one of the rarest species of waterfowl in the world, is seriously threatened with extinction. The birds are native only to the Hawaiian Islands and in 1956 became Hawaii's official bird. The Nene is a protected species and though it will appear on the duck stamp, it may nowhere be hunted. A specialized cousin of the Canada goose, the Nene in the wild lives only at an elevation of between 5,000 and 8,000 feet. It has been away from the water so long that its feet are only partly webbed. This year artists were urged to submit designs showing various species of waterfowl that have not appeared on the 30 previous issues of stamp. -

Focal Species: Hawaiian Goose Or Nēnē (Branta Sandvicensis)

Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan Focal Species: Hawaiian Goose or Nēnē (Branta sandvicensis) Synopsis: The Hawaiian Goose, commonly known as the Nēnē, is the State bird of Hawai’i and is one of the best examples of species recovery by captive breeding. Nēnē were extirpated from all islands except Hawai’i by the 1950s, and their numbers fell to fewer than 50 birds. A captive Geographic region: Hawaiian Islands breeding program began in 1949, and over 2,800 Nēnē Taxonomic Group: Waterbirds have been released on four islands. Nēnē numbers Federal Status: Endangered have grown rapidly on Kaua’i, where mongooses are State status: Endangered not established and high quality lowland habitat is IUCN status: Vulnerable more prevalent; populations on other islands have been Conservation score: 17/20, At-risk periodically supplemented with captive-bred birds. Watch List 2007 Score: RED Conservation actions focus on control of non-native Climate Change Score: LOW predators and restoration of high quality habitat. Nēnē at Volcanoes National Park (left) and Hanalei NWR Kaua’i. Photos E. VanderWerf. Population Size and Trend: In 2011, the Nēnē population was estimated to be 2,465-2,555 birds, including 416 on Maui, 83 on Moloka’i, 1,424-1,514 on Kaua’i, and 542 on Hawai’i (Nēnē Recovery Action Group, unpubl. data). The total population has increased since 2005, when the number of birds was estimated to be 1,754. This increase was caused largely by growth of the Kaua’i population, which grew from 829 birds in 2005 (USFWS 2011). Populations on other islands have been stable or increased slightly, despite periodic releases of captive-bred birds. -

Parasites of Wild and Captive Nene Branta Sandvicensis in Hawaii

Parasites of wild and captive Nene Branta sandvicensis in Hawaii TOM BAILEYand JEFFREYBLACK The risk of introducing disease or parasites into the wild has long concerned managers involved in the Nene recovery programme. In this initial survey helminth eggs were found in samples from 17 of 77free-ranging Nene and eight of 28 captive Nene, giving an overall prevalence of 22%. Percent prevalence, estimated for each of the nine collection sites, was not correlated with bird density. No haemoparasites were detected on micro- scopic examination of the blood smears. A longer term study to determine the dynamics of the Nene-parasite relationship is needed to confirm the initial suggestion that the birds' recovery probably is not limited by heavy parasite infection. Keywords: Nene, Hawaiian Goose, Parasites, Threatened Species The Hawaiian Goose or Nene Branta the risk of disease in threatened popula· sandvicensis is the only endemic goose tions, especially where captive animals surviving on the Hawaiian archipelago are involved through reintroduction pro- and, in 1951,there were just 30 Nene left grammes (Scott et al; 1986, Seal 1991). in the wild (Smith 1952). An intensive Endemic Hawaiian avifauna evolved in international captive breeding and the absence of many diseases common release programme has succeeded in in continental areas and it is believed reintroducing many Nene to the wild. that a reduction in the effectiveness of Restocking began in 1960 and there are immunogenic mechanisms has occurred 500 Nene currently living in the wild on (van Riper & van Riper 1985). Thus, three of the larger Hawaiian islands when native birds encounter introduced (Black et al.