Olmstead V. United States: the Constitutional Challenges of Prohibition Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 59, Issue 1

Volume 60, Issue 4 Page 1023 Stanford Law Review THE SURPRISINGLY STRONGER CASE FOR THE LEGALITY OF THE NSA SURVEILLANCE PROGRAM: THE FDR PRECEDENT Neal Katyal & Richard Caplan © 2008 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, from the Stanford Law Review at 60 STAN. L. REV. 1023 (2008). For information visit http://lawreview.stanford.edu. THE SURPRISINGLY STRONGER CASE FOR THE LEGALITY OF THE NSA SURVEILLANCE PROGRAM: THE FDR PRECEDENT Neal Katyal* and Richard Caplan** INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................1024 I. THE NSA CONTROVERSY .................................................................................1029 A. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act................................................1029 B. The NSA Program .....................................................................................1032 II. THE PRECURSOR TO THE FDR PRECEDENT: NARDONE I AND II........................1035 A. The 1934 Communications Act .................................................................1035 B. FDR’s Thirst for Intelligence ....................................................................1037 C. Nardone I...................................................................................................1041 D. Nardone II .................................................................................................1045 III. FDR’S DEFIANCE OF CONGRESS AND THE SUPREME COURT..........................1047 A. Attorney General -

Jenny Parker Mccloskey, 215-409-6616 Merissa Blum, 215-409-6645 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jenny Parker McCloskey, 215-409-6616 Merissa Blum, 215-409-6645 [email protected] [email protected] NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER TO BRING BACK PROHIBITION IN MARCH 2017 Original exhibit, American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, returns for a limited engagement Exhibit opens Friday, March 3 Philadelphia, PA (January 5, 2017) – The National Constitution Center is bringing back American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, its critically acclaimed exhibit that brings the story of Prohibition vividly to life. The exhibit, created by the National Constitution Center, originally debuted in 2012 and has since toured nationally, including stops at the Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry in Washington, Grand Rapids Public Museum in Michigan, and Peoria Riverfront Museum in Illinois. It will open to the public Friday, March 3 and run through July 16, 2017. An exclusive, members-only sneak preview opening party is planned for Thursday, March 2. The event will include an America’s Town Hall panel discussion on the constitutionality of Prohibition and its impact on American society today. “We are thrilled to have this superb exhibit back from its national tour,” said President and CEO Jeffrey Rosen. “American Spirits brings the U.S. Constitution to life. Visitors can educate themselves about the constitutional legacy of Prohibition and how to amend the Constitution today.” The exhibit uses a mix of artifacts and engaging visitor activities to take visitors back in time to the dawn of the temperance movement, through the Roaring ’20s, and to the unprecedented repeal of a constitutional amendment. -

Prohibition (1920-1933) Internet Assignment

Prohibition (1920-1933) Internet Assignment Name______________________________________ Period_____ Go to: https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/ Click on “Roots of Prohibition” Read the section and answer the questions below. 1. By 1830, the average American over 15 years old consumed nearly _______ gallons of pure alcohol a year. 2. In which institutions did the Temperance Movement have their “roots”? Watch the short video entitled, “The Absolute Shall” 3. Why were the Washingtonian Societies rejected by the Protestant Churches of the 1830s and 1840s? 4. What was the anti-alcohol movement started by the Protestant churches called? 5. What was the “Cold Water Army”? Read the sections about the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League. 6. Which two famous “suffragettes” were also involved with the Temperance Movement? 7. Who was the leader of the Anti-Saloon League? 8. Why did the ASL support the 16th Amendment making an income tax constitutional? 9. What types of propaganda did the ASL put forth during the years leading up to World War I? Page | 1 Go back to the top of the screen and click on “Prohibition Nationwide.” This will take you to a map. Click on the bottle depicted in the Pacific Northwest. Watch the video entitled, “The Good Bootlegger” about Roy Olmstead and his Pacific NW Bootleggers. 10. What was Roy Olmstead’s job? 11. After being convicted of bootlegging alcohol & losing his job, what did Olmstead decide to do? 12. From which country did Olmstead and his employees get the alcohol? 13. What were some of the ways in which Olmstead and his employees distributed the alcohol? 14. -

Preliminary Draft

PRELIMINARY DRAFT Pacific Northwest Quarterly Index Volumes 1–98 NR Compiled by Janette Rawlings A few notes on the use of this index The index was alphabetized using the wordbyword system. In this system, alphabetizing continues until the end of the first word. Subsequent words are considered only when other entries begin with the same word. The locators consist of the volume number, issue number, and page numbers. So, in the entry “Gamblepudding and Sons, 36(3):261–62,” 36 refers to the volume number, 3 to the issue number, and 26162 to the page numbers. ii “‘Names Joined Together as Our Hearts Are’: The N Friendship of Samuel Hill and Reginald H. NAACP. See National Association for the Thomson,” by William H. Wilson, 94(4):183 Advancement of Colored People 96 Naches and Columbia River Irrigation Canal, "The Naming of Seward in Alaska," 1(3):159–161 10(1):23–24 "The Naming of Elliott Bay: Shall We Honor the Naches Pass, Wash., 14(1):78–79 Chaplain or the Midshipman?," by Howard cattle trade, 38(3):194–195, 202, 207, 213 A. Hanson, 45(1):28–32 The Naches Pass Highway, To Be Built Over the "Naming Stampede Pass," by W. P. Bonney, Ancient Klickitat Trail the Naches Pass 12(4):272–278 Military Road of 1852, review, 36(4):363 Nammack, Georgiana C., Fraud, Politics, and the Nackman, Mark E., A Nation within a Nation: Dispossession of the Indians: The Iroquois The Rise of Texas Nationalism, review, Land Frontier in the Colonial Period, 69(2):88; rev. -

Prohibition Era Dinner Party

PROHIBITION ERA DINNER PARTY OVERVIEW Many noteable Americans played many roles during the Prohibition era, from government officials and social reformers to bootleggers and crime bosses. Each person had his or her own reasons for supporting or opposing Prohibition. What stances did these individuals take? What legal, moral, and ethical questions did they have to wrestle with? Why were their actions important? And how might a "dinner party" attended by them bring some of these questions to the surface? related activities PROHIBITION SMART BOARD WHO SAID IT? THE RISE & FALL OF PICTIONARY ACTIVITY QUOTE SORTING PROHIBITION ESSAY Use your skills to get Learn about Learn about the Learn about the classmates to identify Prohibition through differences between background of the and define which informational slides the Founders’ and 18th Amendment, Prohibition era term and activities using the Progressives’ beliefs the players in the you draw. SMART platform. about government by movement, and its sorting quotes from eventual repeal. each group. Made possible in part Developed in by a major grant from partnership with TEACHER NOTES LEARNING GOALS EXTENSION Students will: The son of Roy Olmstead said about his father: “My dad thought that Prohibition was • Understand the significance of historical an immoral law. So he had no compunction figures during the Prohibition era. [misgivings or guilt] about breaking that law.” • Understand the connections between Discuss the statement as a large group. Then different groups during the Prohibition have students respond to the statement in a era. short essay. They should consider the following questions: • Evaluate the tension that sometimes exists between following the law and • How can you know if a law is immoral? following one’s conscience. -

Prohibition in the Taft Court Era

William & Mary Law Review Volume 48 (2006-2007) Issue 1 Article 2 October 2006 Federalism, Positive Law, and the Emergence of the American Administrative State: Prohibition in the Taft Court Era Robert Post Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation Robert Post, Federalism, Positive Law, and the Emergence of the American Administrative State: Prohibition in the Taft Court Era, 48 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1 (2006), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol48/iss1/2 Copyright c 2006 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr William and Mary Law Review VOLUME 48 No.1, 2006 FEDERALISM, POSITIVE LAW, AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE AMERICAN ADMINISTRATIVE STATE: PROHIBITION IN THE TAFT COURT ERAt ROBERT POST* ABSTRACT This Article offers a detailed analysis of major Taft Court decisions involving prohibition, including Olmstead v. United States, Carroll v. United States, United States v. Lanza, Lambert v. Yellowley, and Tumey v. Ohio. Prohibition,and the Eighteenth Amendment by which it was constitutionally entrenched, was the result of a social movement that fused progressive beliefs in efficiency with conservative beliefs in individualresponsibility and self-control. During the 1920s the Supreme Court was a strictly "bone-dry" institution that regularly sustained the administrative and law enforcement techniques deployed by the federal government in its t This Article makes extensive use of primary source material, including the papers of members of the Taft Court. All unpublished sources cited herein are on file with the author. -

THE NEGLECTED HISTORY of CRIMINAL PROCEDURE, 1850-1940 Wesley Macneil Oliver*

THE NEGLECTED HISTORY OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE, 1850-1940 Wesley MacNeil Oliver* INTRODUCTION .......................................... ...... 447 I. HEAVILY-REGULATED "PETTY OFFICERS" (1641-1845) ............ 449 II. ESSENTIALLY UNREGULATED POWERFUL AND CORRUPT POLICE (1845-1921) ...................................... ...... 459 A. Steady Increase in Investigatory Powers ...... ...... 461 B. Police Commissioners Encouraged Police Violence on the Streets ............................. ....... 468 C. Courts Encouraged Police Violence in Interrogation Rooms........................................ 483 III. JUDICIALLY SUPERVISED MODERN POLICE (1921-PRESENT) ........ 493 A. Rampant Corruption and Police Excesses Undermined Myth of Police Perfectability ...... ..... 494 B. New York Judiciary Restored Limits on Interrogations ........................ .......... 510 C. Calls for Exclusionary Rule and Limits on Wiretapping After Prohibition ............... ...... 515 CONCLUSION................................... ............ 523 INTRODUCTION In considering constitutional limits on police investigations, courts and commentators rely on only a small part of the relevant history. No doubt driven by the rising influence of originalism, historical inquiries focus on Framing Era rules limiting constables and watchmen. There are, however, vast differences between eighteenth century and twenty-first century police practices, and vast differences in society's goals in regulating them. Professional * Associate Professor, Widener Law School. B.A., J.D., University of Virginia; LL.M, J.S.D.,Yale. This article is adapted from the final chapter of my J.S.D. dissertation. In this work, I have greatly benefited from the advice and suggestions of a number of persons including Bruce Ackerman, Ben Barros, John Dernbach, Alan Dershowitz, Bob Gordon, Kevin LoVecchio, Ken Mack, Chris Robertson, Chris Robinette, Carol Steiker, Kate Stith, and Bill Stuntz. I have had the great privilege of working with simply excellent librarians at the Widener Law Library, specifically Ed Sonnenberg and Pat Fox. -

SPRING/Summer 2017 Maryland Blood: an American Family in War and Peace, the Hambletons 1657 to the Present

MARYLAND Hisorical Magazine SPRING/SUMMeR 2017 Maryland Blood: An American Family in War and Peace, the Hambletons 1657 to the Present Martha Frick Symington Sanger At the dawn of the seventeenth century, immigrants to this country arrived with dreams of conquering a new frontier. Families were willing to embrace a life of strife and hardship but with great hopes of achieving prominence and wealth. Such is the case with the Hambleton family. From William Hambleton’s arrival on the Eastern Shore in 1657 and through every major confict on land, sea, and air since, a member of the Hambleton clan has par- ticipated and made a lasting contribution to this nation. Teir achievements are not only in war but in civic leadership as well. Among its members are bankers, business leaders, government ofcials, and visionaries. Not only is the Hambleton family extraordinary by American standards, it is also re- markable in that their base for four centuries has been and continues to be Maryland. Te blood of the Hambletons is also the blood of Maryland, a rich land stretching from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean to the tidal basins of the mighty Chesapeake to the mountains of the west, a poetic framework that illuminates one truly American family that continues its legacy of building new genera- tions of strong Americans. Martha Frick Symington Sanger is an eleventh-gen- eration descendant of pioneer William Hambleton and a great-granddaughter of Henry Clay Frick. She is the author of Henry Clay Frick: An Intimate Portrait, Te Henry Clay Frick Houses, and Helen Clay Frick: Bitter- sweet Heiress. -

Hellfire Nation: the Politics of Sin in American History

More praise for Hellfire Nation “In a beautifully written book, Morone has integrated the history of American political thought with a perceptive study of religion’s role in our public life. May Hellfire Nation encourage Americans to discover (or rediscover) the ‘moral dreams that built a nation.’”—E. J. Dionne, syndi- cated columnist and author of Why Americans Hate Politics and They Only Look Dead “This is a remarkably broad, sweeping account, written with verve and passion.”—James T. Patterson, author of Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy “Morone is an exciting writer. Rich in documentation and eloquent in purpose, Hellfire Nation couldn’t be more timely.”—Tom D’Evelyn, Providence Journal “Hellfire Nation offers convincing evidence that no political advance has ever taken place in the United States without a moral awakening flushed with notions about what the Lord would have us do. It’s enough to make a secular leftist gag—and then grudgingly acknowledge the power of prayer.”—Michael Kazin, Nation “This book’s provocative thesis, ambitious scope, and brisk prose ensure that it will appeal to a broad readership.”—Harvard Law Review “[Morone] has written a book for people with no special training in American cultural history. His aim seems to be to meditate on the long history of Christian-based political movements. He wants to encourage people to rethink the possibilities and limitations of the American ten- dency to conflate religion and politics. Morone has succeeded in meeting these worthwhile goals, and he has done so through a set of engrossing narratives. -

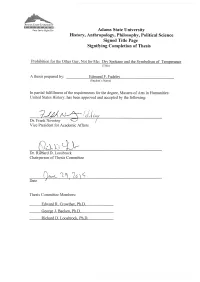

Adams State University History, Anthropology, Philosophy, Political Science Signed Title Page Signifying Completion of Thesis I

Adams State University History, Anthropology, Philosophy, Political Science Signed Title Page Signifying Completion of Thesis Prohibition for the Other Guy, Not for Me: Dry Spokane and the Symbolism of Temperance (Title) A thesis prepared by: --------'E=d=m=m=1d=-=-F:....:.F'-'a=d=e.:..:le:;.Ly ___________ _ (Student's Name) In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Masters of Arts in HUlllanities: United States History, has been approved and accepted by the following: Dr. Frank N~votny I Vice President for Academic Affairs Dr. Ric 1ard D. Loosbrock Chairperson of Thesis Committee Date I 1 Thesis Committee Members: Edward R. Crowther Ph.D. George J. Backen, Ph.D. Richard D. Loosbrock, Ph.D. Prohibition for the Other Guy, Not For Me: Dry Spokane and The Symbolism of Temperance By Edmund "Ned" Fadeley A Thesis Submitted to Adams State College in partial fulfillment of M.A. in United States History August, 2015 ABSTRACT By Edmund "Ned" Fadeley In Washington State, the era of Prohibition spanned more than fifteen parched years. Begim1ing with the passage of the anti-saloon Initiative Number Three in 1914 and closing with the repeal of statewide Prohibition more than a full year before the 1933 ratification of the Twenty First Amendment, the Evergreen State's experience with de jure temperance continues to provide students of American history with fresh opportunities for reappraisal. Using the city of Spokane, the largest between Minneapolis and Seattle, as a lens through which to evaluate the legitimacy of popular memory's cynical appraisal of the nation's Dry years, one encounters two particular historical constructs of enduring salience. -

EXAMINING PROHIBITION in 1920S USA Michael Sweet School of Law

A MEASURE OF SUCCESS: EXAMINING PROHIBITION IN 1920s USA Michael Sweet School of Law Murdoch University This thesis is presented for the degree of Master of Laws by Research Murdoch University, 2017 ii Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary educational institution. Michael Sweet 2017 iii Abstract In 1919, a policy to ban alcoholic beverages was entrenched by Congress into the Constitution - the 18th Amendment. Congressmen Andrew Volstead proceeded to promote the enacting legislation in the United States House of Representatives, and the National Prohibition Act became law. Does Prohibition deserve its overwhelming condemnation as a failure? How successful was the Act’s implementation? After the introduction, part two discusses the theories and perceptions that serve to shape the debate over alcohol prohibition. To measure its success, the Act is then examined according to its outcomes - part three of the thesis assesses the anticipated increase in economic prosperity through the metrics of government revenue, business activity, workplace attendance, wages and sales figures. Part four scrutinises the production and supply of alcohol, prison populations, drunkenness, crime rates and corruption. The success of a reform is also found in how it shapes the nation. Prohibition’s economic and political effects are briefly noted, as is its influence upon policing and the judiciary. The 21st Amendment repealing alcohol prohibition functioned to skew reporting of the Prohibition era, serving the purposes of ideologues and business opportunists. The thesis concludes that the reform was not defeated by any inherent impossibility, but rather by a lack of skilfully wielded political will. -

Nuanced but Never Dry

Nuanced but Never Dry By JULIA M. KLEIN American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition National Constitution Center Through April 28 Philadelphia Mention Prohibition, and the images flow: flappers, speakeasies, gangsters, bootleggers. The national fascination with the period still infuses popular culture, inspiring shows such as HBO's violent, sexually charged "Boardwalk Empire." The National Constitution Center's new exhibition, "American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition," duly features a re-created speakeasy, beaded dresses and mug shots of gangsters, as well as "untouchable" Prohibition agent Eliot Ness's oath of office. But the show, which will travel to at least five other venues, also offers a more nuanced examination of this strange interlude, from 1920 to 1933, during which law breaking was invested with a rare glamor. Balancing the imperative to entertain with serious history was "the hardest part" of crafting "American Spirits," says curator Daniel Okrent, the author of "Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition." The aim was "to be fun, first and foremost," says Stephanie Reyer, the center's vice president of exhibitions. The National Constitution Center's new exhibition, "American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition," offers a more nuanced view of the Prohibition era. The center is billing "American Spirits" as the "first comprehensive exhibition about Prohibition." Exhibits illustrate the country's longstanding love affair with alcohol; the surprising links between Prohibition, suffrage and the federal income tax; the era's impact on Fourth Amendment protections against "unreasonable searches and seizures," and the economics of repeal. But visitors can also get their photos taken in a lineup with Al Capone and Lucky Luciano, chase rumrunners in a video game, and learn to dance the Charleston.