Jerry Herman's Leading Ladies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directing and Assisting Credits American Theatre

917-854-2086 American and Canadian citizen Member of SSDC www.joelfroomkin.com [email protected] Directing and Assisting Credits American Theatre Artistic Director The New Huntington Theatre, Huntington Indiana. The Supper Club (upscale cabaret venue housing musical revues) Director/Creator Productions include: Welcome to the Sixties, Hooray For Hollywood, That’s Amore, Sounds of the Seventies, Hoosier Sons, Puttin’ On the Ritz, Jekyll and Hyde, Treasure Island, Good Golly Miss Dolly, A Christmas Carol, Singing’ The King, Fly Me to the Moon, One Hit Wonders, I’m a Believer, Totally Awesome Eighties, Blowing in the Wind and six annual Holiday revues. Director (Page on Stage one-man ‘radio drama’ series): Sleepy Hollow, Treasure Island, A Christmas Carol, Jekyll and Hyde, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, Different Stages (320 seat MainStage) The Sound of Music (Director/Scenic & Projection Design) Moonlight and Magnolias (Director/Scenic Design) Les Misérables (Director/Co-Scenic and Projection Design) Productions Lord of the Flies (Director) Manchester University The Laramie Project (Director) Manchester University The Foreigner (Director) Manchester University Infliction of Cruelty (Director/Dramaturg) Fringe NYC, 2006 *Winner of Fringe 2006 Outstanding Excellence in Direction Award Thumbs, by Rupert Holmes (Director) Cape Playhouse, MA *Cast including Kathie Lee Gifford, Diana Canova (Broadway’s Company, They’re Playing our Song), Sean McCourt (Bat Boy), and Brad Bellamy The Fastest Woman Alive (Director) Theatre Row, NY *NY premiere of recently published play by Outer Critics Circle nominee, Karen Sunde *published Broadway Musicals of 1928 (Director) Town Hall, NYC *Cast including Tony-winner Bob Martin, Nancy Anderson, Max Von Essen, Lari White. -

Senior Musical Theater Recital Assisted by Ms

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Joy Kenyon Senior Musical Theater Recital assisted by Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble Women’s Chorus, Scott Foreman, Daniel Bravo James Kenyon, & Jessica Ziegelbauer Monday, April 13, 2015 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert Please turn off all cell phones and electronics. PROGRAM Just Leave Everything To Me from Hello Dolly Jerry Herman • b. 1931 100 Easy Ways To Lose a Man from Wonderful Town Leonard Bernstein • 1918 - 1990 Betty Comden • 1917 - 2006 Adolph Green • 1914 - 2002 Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist The Man I Love from Lady, Be Good! George Gershwin • 1898 - 1937 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Love is Here To Stay from The Goldwyn Follies Embraceable You from Girl Crazy Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist; Scott Foreman, Bass Guitar; Daniel Bravo, Percussion Steam Heat (Music from The Pajama Game) Choreography by Mrs. Kellis McSparrin Oldenburg Dancer: Joy Kenyon He Lives in You (reprise) from The Lion King Mark Mancina • b. 1957 Jay Rifkin & Lebo M. • b. 1964 arr. Dr. Owen Rockwell Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble; Maddi Jolley, Brooke Kressin, Grace Anna Randall, Mariah Taylor, Elizabeth Walczak, Rachel Walczak, Evangeline Wilds, Julie Wolfe & Jessica Ziegelbauer INTERMISSION The Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim • b. 1930 Sweet Liberty from Jane Eyre Paul Gordon • b. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

The Manchurian Candidate (1962) Directed by John Frankenheimer

Why Don’t You Pass the Time by Playing a Little Solitaire? By Fearless Young Orphan The Manchurian Candidate (1962) Directed by John Frankenheimer I saw it: August 19, 2010 Why haven’t I seen it yet? For the longest time, I didn’t even know what it was supposed to be about, or that it was supposed to be any good. It seemed like one of those movies that is famous for its confusing title. I even saw the 2004 remake first, and then this little beauty turned up on my list of classics. Candidate A platoon of American soldiers stationed in Korea comes under attack. Most of the platoon is rescued by Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey), who displays such valiant behavior that he is awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor upon his return. This is good news for his mother, the Mrs. Iselin who is married to Senator Iselin (who, Raymond assures everyone adamantly, is only Raymond’s stepfather). Mrs. Iselin would like her husband to become the Vice President of the United States, and it certainly doesn’t hurt matters to have a hero in the family. Angela Lansbury, icy and quite beautiful, eats this role alive; she may be one of the most evil and frightening characters I’ve ever seen in a film. What is amusing about her is that we know from the moment we hear her speak that she is a villain, long before we know exactly what the hell she’s up to. Her son hates and fears her; he can’t get away from her fast enough. -

MUSICAL NOTES a Guide to Goodspeed Musicals Productions 2009 Season

MUSICAL NOTES A Guide to Goodspeed Musicals Productions 2009 Season Musical Notes is made possible through the generosity of Music by HARRY WARREN Lyrics by AL DUBIN Book by MICHAEL STEWART and MARK BRAMBLE Directed by RAY RODERICK Choreographed by RICK CONANT Scenery Design Costume Design Lighting Design HOWARD JONES DAVID H. LAWRENCE CHARLIE MORRISON Hair and Wig Design Sound Orchestrations Music Supervisor Music Director MARK ADAM RAMPMEYER JAY HILTON DAN DELANGE MICHAEL O’FLAHERTY WILLIAM J. THOMAS Production Manager Production Stage Manager Casting R. GLEN GRUSMARK BRADLEY G. SPACHMAN STUART HOWARD ASSOCIATES, PAUL HARDT Associate Producer Line Producer BOB ALWINE DONNA LYNN COOPER HILTON Produced for Goodspeed Musicals by MICHAEL P. PRICE Cast of Characters Andy Lee………………………………………………………TIM FALTER Maggie Jones…………………………………………………..DOROTHY STANLEY Bert Barry………………………………………………………DALE HENSLEY Phyllis Dale…………………………………………………….ELISE KINNON Lorraine Fleming……………………………………………….ERIN WEST Ann Reilly……………………………………………………....JENIFER FOOTE Billy Lawlor…………………………………………………….AUSTIN MILLER Peggy Sawyer…………………………………………………..KRISTEN MARTIN Julian Walsh…………………………………………………….JAMES LLOYD REYNOLDS Dorothy Brock………………………………………………….LAURIE WELLS Abner Dillon……………………………………………………ERICK DEVINE Pat Denning…………………………………………………….JONATHAN STEWART Ensemble……………………………………………………….ALISSA ALTER KELLY DAY BRANDON DAVIDSON ERIN DENMAN TIM FALTER JOE GRANDY CHAD HARLOW ELISE KINNON ASHLEY PEACOCK KRISTYN POPE COLIN PRITCHARD ERNIE PRUNEDA TARA JEANNE VALLEE ERIN WEST Swings TYLER ALBRIGHT EMILY THOMPSON Biographies Harry Warren and Al Dubin (Music and Lyrics) Harry Warren and Al Dubin were legendary tunesmiths both as a team and as individuals. Between the two, their prodigious careers spanned six decades. They wrote Broadway shows and revues and were pioneer song- writers for sound pictures. Their combined output of songs can only be described as astonishing. Al Dubin, born in Switzerland in 1891, died in New York in 1945. -

A Comedy Revolution Comes to Starlight Indoors This Winter

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Rachel Bliss, Starlight Theatre [email protected] 816-997-1151-office 785-259-3039-cell A Comedy Revolution Comes to Starlight Indoors This Winter Playing November 5-17 only! “SMART, SILLY AND “SPAMILTON IS SO “THE NEXT BEST THING CONVULSIVELY FUNNY” INFECTIOUSLY FUN THAT IT TO SEEING HAMILTON!” - The New York Times COULD EASILY RUN AS LONG - New York Post AS ITS INSPIRATION!” – The Hollywood Reporter KANSAS CITY, Mo. – As the weather cools off, the stage house heats up with the 2019-20 Starlight Indoors series, sponsored by the Missouri Lottery. Now in its fifth season, this year’s lineup of hilarious Off-Broadway hits opens November 5-17 with the North American tour of Spamilton: An American Parody, making its Kansas City premiere. Tickets are on sale now. Created by Gerard Alessandrini, the comic mastermind behind the long-running hit Forbidden Broadway, which played the 2017-18 Starlight Indoors series, Spamilton: An American Parody is a side-splitting new musical parody based on a blockbuster hit of a similar name. After numerous extensions of its run in New York, this hilarious production made a splash in Chicago, Los Angeles and London. Now, Spamilton: An American Parody brings a singing, dancing and comedy revolution to Kansas City. “Spamilton pays a hilarious tribute to its inspiration and is smart, sharp and funny to its core— everything you’d want and more from a spoof of Broadway’s most popular musical,” Caroline Gibel, director of indoor programming at Starlight, said. “The best part is, you don’t have to have seen Hamilton to enjoy Spamilton. -

Mabel's Blunder

Mabel’s Blunder By Brent E. Walker Mabel Normand was the first major female comedy star in American motion pictures. She was also one of the first female directors in Hollywood, and one of the original principals in Mack Sennett’s pioneering Keystone Comedies. “Mabel’s Blunder” (1914), made two years after the formation of the Keystone Film Company, captures Normand’s talents both in front of and behind the camera. Born in Staten Island, New York in 1892, a teenage Normand modeled for “Gibson Girl” creator Charles Dana Gibson before entering motion pictures with Vitagraph in 1910. In the summer of 1911, she moved over to the Biograph company, where D.W. Griffith was making his mark as a pioneering film director. Griffith had already turned actresses such as Florence Lawrence and Mary Pickford into major dramatic stars. Normand, however, was not as- signed to the dramas made by Griffith. Instead, she went to work in Biograph’s comedy unit, directed by an actor-turned-director named Mack Sennett. Normand’s first major film “The Diving Girl” (1911) brought her notice with nickelodeon audiences. A 1914 portrait of Mabel Normand looking Mabel quickly differentiated herself from the other uncharacteristically somber. Courtesy Library of Congress Biograph actresses of the period by her willingness Prints & Photographs Online Collection. to engage in slapstick antics and take pratfalls in the name of comedy. She also began a personal ro- to assign directorial control to each of his stars on mantic relationship with Mack Sennett that would their comedies, including Normand. Mabel directed have its ups and downs, and would eventually in- a number of her own films through the early months spire a Broadway musical titled “Mack and Mabel.” of 1914. -

Woody & Linda Brownlee 190 @ Jupiter Office

The Garland Summer Musicals in partnership with RICHLAND COLLEGE proudly presents Woody & Linda Brownlee 190 @ Jupiter Office Granville Arts Center Garland, Texas Office Location: June 17-26, 2011 3621 Shire Blvd. Ste. 100 Richardson, Texas 75082 Presented through special grants from GARLAND CULTURAL ARTS COMMISSION, INC. 214-808-1008 Cell Linda GARLAND SUMMER MUSICALS GUILD 972-989-9550 Cell Woody GARLAND POWER & LIGHT [email protected] ALICE & GORDON STONE [email protected] ECOLAB, INC. www.brownleeteam.ebby.com MICROPAC INDUSTRIES Garland Summer Musicals Presents Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Broadway Blockbuster CATS! July 22, 23, 29, 30 at 8pm July 24, 31 at 2:30pm Tickets: $27 - Adults; $25 - Seniors/Students; $22 - Youth Special discounts for season tickets, corporate sales and groups GRANVILLE ARTS CENTER - 300 N. Fifth Street, Garland, Texas 75040 Call the Box Office at 972-205-2790 The Garland Summer Musicals Guild presents Dallas' most famous entertainment group The Levee Singers Saturday, September 24, 2011 Plaza Theatre 521 W. State Street—Garland, TX The Levee Singers are celebrating their 50th anniversary this year and are busier and better than ever! Come join the GSM Guild as they present this spectacular fun-filled evening with the Levee Singers. For tickets call 972-205-2790. THE GARLAND SUMMER MUSICALS SPECIAL THANKS Presents MEREDITH WILLSON’S GARLAND SUMMER MUSICALS GUILD “The Music Man” SACHSE HIGH SCHOOL—Joe Murdock and Libby Nelson Starring THE SACHSE HIGH SCHOOL TECHNICAL CLASS STAN GRANER JACQUELYN LENGFELDER NAAMAN FOREST HIGH SCHOOL BAND—Larry Schnitzer Featuring NORTH GARLAND HIGH SCHOOL—Mikey Abrams & Nancy Gibson JAMES WILLIAMS MELISSA TUCKER J.J. -

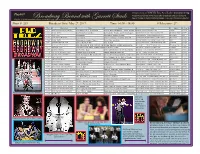

Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack

Originating on WMNR Fine Arts Radio [email protected] Playlist* Program is archived 24-48 hours after broadcast and can be heard Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack free of charge at Public Radio Exchange, > prx.org > Broadway Bound *Playlist is listed alphabetically by show (disc) title, not in order of play. Show #: 269 Broadcast Date: May 27, 2017 Time: 16:00 - 18:00 # Selections: 27 Time Writer(s) Title Artist Disc Label Year Position Comment File Number Intro Track Holiday Release Date Date Played Date Played Copy 3:24 Menken|Ashman|Rice|Beguelin Somebody's Got Your Back James Monroe Iglehart, Adam Jacobs & Aladdin Original Broadway Cast Disney 2014 Opened 3/20/2014 CDS Aladdin 15 2014 8/16/14 12/6/14 1/7/17 5/27/17 3:17 Irving Berlin Anything You Can Do Bernadette“friends” Peters and Tom Wopat Annie Get Your Gun - New Broadway Cast Broadway Angel 1999 3/4/1999 - 9/1/2001. 1045 perf. 2 Tony Awards: Best Revival. Best Actress, CDS Anni none 18 1999 6/7/08 5/27/17 Bernadette Peters. 3:30 Cole Porter Friendship Joel Grey, Sutton Foster Anything Goes - New Broadway Cast 2011 Ghostlight 2011 Opened 4/7/11 at the Stephen Sondheim Theater. THREE 2011 Tony Awards: Best Revival CDS Anything none 9 2011 12/10/113/31/12 5/27/17 of a Musical; Best Actress in a Musical: Sutton Foster; Best Choreography: Kathleen 2:50 John Kander/Fred Ebb Two Ladies Alan Cumming, Erin Hill & Michael Cabaret: The New Broadway Cast Recording RCA Victor 1998 3/19/1998 - 1/4/2004. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with James Earl Jones

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with James Earl Jones PERSON Jones, James Earl Alternative Names: James Earl Jones; Life Dates: January 17, 1931- Place of Birth: Arkabutla, Mississippi, USA Work: Pawling, NY Occupations: Actor Biographical Note Actor James Earl Jones was born on January 17, 1931 to Robert Earl Jones and Ruth Connolly in Arkabutla, Mississippi. When Jones was five years old, his family moved to Dublin, Michigan. He graduated from Dickson High School in Brethren, Michigan in 1949. In 1953, Jones participated in productions at Manistee Summer Theatre. After serving in the U.S. Army for two years, Jones received his B.A. degree from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in 1955. Following graduation, Jones relocated to New York City where he studied acting at the American Theatre Wing. Jones’ first speaking role on Broadway was as the valet in Sunrise at Campobello in 1958. Then, in 1960, Jones acted in the Shakespeare in Central Park production of Henry V while also playing the lead in the off-Broadway production of The Pretender. Geraldine Lust cast Jones in Jean Genet’s The Blacks in the following year. In 1963, Jones made his feature film debut as Lt. Lothar Zogg in Dr. Strangelove, directed by Stanley Kubrick. In 1964, Joseph Papp cast Jones as Othello for the Shakespeare in Central Park production of Othello. Jones portrayed champion boxer Jack Jefferson in the play The Great White Hope in 1969, and again in the 1970 film adaptation. His leading film performances of the 1970s include The Man (1972), Claudine (1974), The River Niger (1975) and The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings (1976). -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158.