Chapter Nine Irish Diocesan Priesthood, 1962-2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesus Christ, the Returning King

MARCH 2006 VOL. 2 Jesus Christ, The Returning King INSIDE THIS ISSUE: On a trip to the International Divine The painting shows Jesus in all Mercy Shrine in Krakow, Poland, His glory as a King. See Page 2 for Howard Dee, Pg. 2 DFOT in the Philippines Anne received a surprise gift of the the story of how the painting was oil painting below entitled “Jesus Christ given to Anne. Returning King Icon Pg. 2 The Returning King.” Monthly Messages Pg. 3 Fr. Francis Martin, Pg. 4 Focus on Volume Two Howard Dee, Review of Vol. 2 Pg. 5 Clerical Abuse Booklet Reprint Pg. 6 Anne, Attack on Celibacy Pg. 8 Anne, Sexual Abuse Scandals Pg. 9 NEW! Climbing Pg. 10 The Mountain Book Ronda Chervin, Book Review Pg. 10 Anne, Martha and Mary Pg. 11 Anne, Falseness Pg. 12 Fr. Bill McCarthy, “Flowing Love” Pg. 13 Anne, Questions/Answers Pg. 14 Dedicated to Mary, Queen of Apostles © Copyright 2006 Directions For Our Times. All Rights Reserved An Inspiring The Story of the Volumes New Image for the Mission in the Philippines By Howard Dee, Former Philippines Ambassador to the Vatican By Bill Quinn On February 9, 2005, Jesus gave Anne, a lay On September 8, Archbishop (now apostle, the following message: “The Church Cardinal-elect) Gaudencio Rosales of Manila is aware of this mission of mercy and is received me and gave his blessings to the assisting through the cooperation of your Volumes which I had sent him earlier. He bishop. It is I who wills this mission and it was so impressed with the prescribed is I who directs its course.” guidelines for lay apostles that he said he would encourage his diocesan priests to As Providence would have it, on that observe them. -

Chronology of the Martin and Guérin Families***

CHRONOLOGY OF THE MARTIN AND GUÉRIN FAMILIES*** 1777 1849 April 16, 1777 - The birth of Pierre-François Martin in Athis-de- father of Louis Martin. His baptismal godfather was his maternal uncle, François Bohard. July 6, 1789 - The birth of Isidore Guérin, Sr. in St. Martin- father of Zélie Guérin Martin. January 12, 1800 - The birth of Marie-Anne-Fanie Boureau in Blois (Loir et Cher). She was the mother of Louis Martin. July 11, 1805 - The birth of Louise-Jeanne Macé in Pré- en-Pail (Mayenne). She was the mother of Marie-Louise Guérin (Élise) known in religion as Sister Marie-Dosithée, Zélie Guérin Martin and Isidore Guérin. April 4, 1818 - Pierre-François Martin and Marie-Anne- Fanie Boureau were married in a civil ceremony in Lyon. April 7, 1818 - Pierre-François Martin and Marie-Anne- Fanie Boureau were married in Lyon in the Church of Saint-Martin- Abbé Bourganel. They lived at 4 rue Vaubecourt. They were the parents of Louis Martin. July 29, 1819 - The birth of Pierre Martin in Nantes. He was the oldest brother of Louis Martin. He died in a shipwreck when still very young. September 18, 1820 - The birth of Marie-Anne Martin in Nantes. She was the oldest sister of Louis Martin. August 22, 1823 - The birth of Louis-Joseph-Aloys- Stanislaus Martin on the rue Servandoni in Bordeaux (Gironde). He was the son of Pierre-François Martin and Marie- Anne-Fanie Boureau. He was the brother of Pierre, Marie-Anne, Anne-Françoise- Fanny and Anne Sophie Martin. He was 1 the husband of Zélie Guérin Martin and the father of Marie, Pauline, Léonie, Céline and Thérèse (St. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION In August 2002 Mr George Birmingham SC presented a preliminary report on child sexual abuse involving Roman Catholic priests in the Diocese of Ferns to the Minister for Health and Children. Mr Birmingham had been asked by the Minister to investigate the background to allegations of child sexual abuse in the Diocese with a view to recommending an appropriate form and Terms of Reference for an Inquiry to inquire into the issue. As recommended by Mr Birmingham, the Minister for Health and Children established a non-statutory private inquiry to investigate allegations or complaints of child sexual abuse which were made against clergy operating under the aegis of the Diocese of Ferns. The Ferns Inquiry was established as a three-person team under the chairmanship of Mr Justice Francis D Murphy, formerly of the Supreme Court. The two other members of the Inquiry are: Dr Helen Buckley, senior lecturer in the Department of Social Studies, Trinity College, Dublin; and Dr Laraine Joyce, deputy director of the Office for Health Management. The Inquiry was formally established by the Minister for Health and Children on 28 March 2003. Counsel to the Inquiry was Mr Sean Ryan SC and Mr Declan Doyle SC. Mr Ryan was nominated as a Judge of the High Court in September 2003 and was succeeded by Mr Finbarr Fox SC. The Secretrary to the Inquiry was Mrs Marian Shanley BCL Solicitor. Solicitor to the Inquiry was Mr Joseph O’Malley BCL LLM Solicitor, of Hayes Solicitors, Lavery House, Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2. The Inquiry was assisted in its work by the following people: Stephen O’Brien BA, Administrative Officer of the Department of Health and Children; David Begley, Clerical Officer of the Department of Health and Children. -

Proposed Inquiry Into the Handling of Allegations of Child Sex Abuse Relating to the Diocese of Ferns

Proposed inquiry into the handling of allegations into child sex abuse relating to the Diocese of Ferns Item Type Report Authors Department of Health and Children;Birmingham, George Citation Department of Health and Children, Birmingham, George. 2002. Proposed inquiry into the handling of allegations into child sex abuse relating to the Diocese of Ferns. Dublin: Department of Health and Children. Publisher Department of Health and Children Download date 01/10/2021 10:16:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10147/575375 Find this and similar works at - http://www.lenus.ie/hse Proposed Inquiry into the Handling of Allegations of Child Sex Abuse Relating to the Diocese of Ferns A Report to Mr MicheaI Martin TD Minister for Health & Children by Mr George Birmingham SC 1 August 2002 CONTENTS Part I Introduction Background 1 Terms of reference Staffing 2 Disclosures 2 Options 3 Part II Methodology Introduction 4 Current and past inquiries 4 interviews with victims 5 Church co-operation 6 Garda and health board co-operation 8 Interviews with cross-section of interested parties 8 Part III An overview of the factual backdrop Introduction 10 The term 'child sex abuse' 11 Forms of reference to parties 11 Priest' A' 12 Priest' B' 12 Priest 'C' 13 Priest '0': Fr James Grennan 16 Priest' E' 22 Priest 'F': Monsignor Miceal Ledwith 28 Priest 'G' 43 Priest' H' 44 Priest'j': Fr Sean Fortune 49 Priest 'K': Fr Donal Collins 63 Priest'L' 66 Part IV Bishop Brendan Comiskey's response and related issues Introduction 67 Bishop Comiskey's approach to complaints -

Irish Schools Athletics Champions 1916-2015 Updated June 15 2015

Irish Schools Athletics Champions 1916-2015 Updated June 15 2015 In February 1916 Irish Amateur Athletic Association (IAAA) circularised the principal schools in Ireland regarding the advisability of holding Schoolboys’ Championships. At the IAAA’s Annual General Meeting held on Monday 3rd April, 1916 in Wynne’s Hotel, Dublin, the Hon. Secretary, H.M. Finlay, referred to the falling off in the number of affiliated clubs due to the number of athletes serving in World War I and the need for efforts to keep the sport alive. Based on responses received from schools, the suggestion to hold Irish Schoolboys’ Championships in May was favourably considered by the AGM and the Race Committee of the IAAA was empowered to implement this project. Within a week a provisional programme for the inaugural athletics meeting to be held at Lansdowne Road on Saturday 20th May, 1916 had been published in newspapers, with 7 events and a relay for Senior and 4 events and a relay for Junior Boys. However, the championships were postponed "due to the rebellion" and were rescheduled to Saturday 23rd September, 1916, at Lansdowne Road. In order not to disappoint pupils who were eligible for the championships on the original date of the meeting, the Race Committee of the IAAA decided that “a bona fide schoolboy is one who has attended at least two classes daily at a recognised primary or secondary school for three months previous to 20 th May, except in case of sickness, and who was not attending any office or business”. The inaugural championships took place in ‘quite fine’ weather. -

Catholicism and the Judiciary in Ireland, 1922-1960

IRISH JUDICIAL STUDIES JOURNAL 1 CATHOLICISM AND THE JUDICIARY IN IRELAND, 1922-1960 Abstract: This article examines evidence of judicial deference to Catholic norms during the period 1922-1960 based on a textual examination of court decisions and archival evidence of contact between Catholic clerics and judges. This article also examines legal judgments in the broader historical context of Church-State studies and, argues, that the continuity of the old orthodox system of law would not be easily superseded by a legal structure which reflected the growing pervasiveness of Catholic social teaching on politics and society. Author: Dr. Macdara Ó Drisceoil, BA, LLB, Ph.D, Barrister-at-Law Introduction The second edition of John Kelly’s The Irish Constitution was published with Sir John Lavery’s painting, The Blessing of the Colours1 on the cover. The painting is set in a Church and depicts a member of the Irish Free State army kneeling on one knee with his back arched over as he kneels down facing the ground. He is deep in prayer, while he clutches a tricolour the tips of which fall to the floor. The dominant figure in the painting is a Bishop standing confidently above the solider with a crozier in his left hand and his right arm raised as he blesses the soldier and the flag. To the Bishop’s left, an altar boy holds a Bible aloft. The message is clear: the Irish nation kneels facing the Catholic Church in docile piety and devotion. The synthesis between loyalty to the State and loyalty to the Catholic Church are viewed as interchangeable in Lavery’s painting. -

How Different Are the Irish?

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Articles School of Business and Humanities 2015-3 How Different are the Irish? Eamon Maher Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ittbus Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Maher, E. (2015) How Different are the Irish? in Doctrine & Life, Vol. 65, March 2015, no.3, pp. 2-11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Business and Humanities at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License How Different Are the Irish? EAMON MAHER HIS review-article sets about assessing the significance of a new T collection of essays edited by Tom Inglis, Are the Irish Different?1 Tom Inglis is the foremost commentator on the factors that led to the Catholic Church in Ireland securing a 'special position' during the ninetenth and twentieth centuries.2 The Church's 'moral monopoly' has effectively been ceroded by a number of recent developments; the increased secularisation that accompanied greater prosperity, the tendency among a better educated laity to find their own answers to whatever moral dilemmas assail them, and, of course, the clerical abuse scandals. But even in the 1980s, and earlier, change was afoot. We read in Moral Monopoly: The criterion of a good Irish Catholic has traditionally been per ceived as one who received the sacraments regularly and who fol lowed as well as possible the rules and regulations of the Church. -

Sexual Abuse of the Vulnerable by Catholic Clergy Thomas P

Sexual Abuse of the Vulnerable by Catholic Clergy Thomas P. Doyle, J.C.D., C.A.D.C. exual abuse of the vulnerable by Catholic clergy (deacons, priests and bishops) was a little known phenomenon until the mid-eighties. Widespread publicity sur- S rounding a case from a diocese in Louisiana in 1984 began a socio-historical process that would reveal one of the Church’s must shameful secrets, the widespread, systemic sexual violation of children, young adolescents and vulnerable adults by men who hold one of the most trusted positions in our society (cf. Berry, 1992). The steady stream of reports was not obvious was the sexual abuse itself. This Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, contained limited to the southern United States. It was was especially shocking and scandalous an explicit condemnation of sex between soon apparent that this was a grave situa- because the perpetrators were priests and adult males and young boys. There were no tion for the Catholic Church throughout the in some cases, bishops. For many it was clergy as such at that time nor were United States. Although the Vatican at first difficult, if not impossible, to resolve the bishops and priests, as they are now claimed this was an American problem, the contradiction between the widespread ins- known, in a separate social and theological steady stream of revelations quickly spread tances of one of society’s most despicable class. The first legislation proscribing what to other English speaking countries. crimes and the stunning revelation that the later became known as pederasty was pas- Reports in other countries soon confirmed perpetrators were front-line leaders of the sed by a group of bishops at the Synod of what insightful observers predicted: it was largest and oldest Christian denomination, Elvira in southern Spain in 309 AD. -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

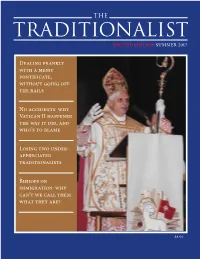

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

Jews, Radical Catholic Traditionalists, and the Extreme Right

“Artisans … for Antichrist”: Jews, Radical Catholic Traditionalists, and the Extreme Right Mark Weitzman* The Israeli historian, Israel J. Yuval, recently wrote: The Christian-Jewish debate that started nineteen hundred years ago, in our day came to a conciliatory close. … In one fell swoop, the anti-Jewish position of Christianity became reprehensible and illegitimate. … Ours is thus the first generation of scholars that can and may discuss the Christian-Jewish debate from a certain remove … a post- polemical age.1 This appraisal helped spur Yuval to write his recent controversial book Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Yuval based his optimistic assessment on the strength of the reforms in Catholicism that stemmed from the adoption by the Second Vatican Council in 1965 of the document known as Nostra Aetate. Nostra Aetate in Michael Phayer’s words, was the “revolution- ary” document that signified “the Catholic church’s reversal of its 2,000 year tradition of antisemitism.”2 Yet recent events in the relationship between Catholics and Jews could well cause one to wonder about the optimism inherent in Yuval’s pronouncement. For, while the established Catholic Church is still officially committed to the teachings of Nostra Aetate, the opponents of that document and of “modernity” in general have continued their fight and appear to have gained, if not a foothold, at least a hearing in the Vatican today. And, since in the view of these radical Catholic traditionalists “[i]nternational Judaism wants to radically defeat Christianity and to be its substitute” using tools like the Free- * Director of Government Affairs, Simon Wiesenthal Center. -

Murphy Report

Chapter 28 Fr William Carney Introduction 28.1 William (Bill) Carney was born in 1950 and was ordained for the Archdiocese of Dublin in 1974. He served in the Archdiocese from ordination until 1989. He was suspended from or had restricted ministry during some of this time. He was dismissed from the clerical state in 1992. 28.2 Bill Carney is a serial sexual abuser of children, male and female. The Commission is aware of complaints or suspicions of child sexual abuse against him in respect of 32 named individuals. There is evidence that he abused many more children. He had access to numerous children in residential care; he took groups of children on holiday; he went swimming with groups of children. He pleaded guilty to two counts of indecent assault in 1983. The Archdiocese paid compensation to six of his victims. He was one of the most serious serial abusers investigated by the Commission. There is some evidence suggesting that, on separate occasions, he may have acted in concert with other convicted clerical child sexual abusers - Fr Francis McCarthy (see Chapter 41) and Fr Patrick Maguire (see Chapter 16). 28.3 A number of witnesses who gave evidence to the Commission, including priests of the diocese, described Bill Carney as crude and loutish. Virtually all referred to his crude language and unsavoury personal habits. One parent told the Commission that the family had complained to the parish priest about his behaviour but the parish priest said there was nothing he could do. 28.4 In 1974, the year Fr Carney was ordained, the President of Clonliffe College, when assessing him for teaching, reported to Archbishop Dermot Ryan that Fr Carney was “very interested in child care” and was “best with the less intelligent”. -

Nick Davis Film Discussion Group December 2015

Nick Davis Film Discussion Group December 2015 Spotlight (dir. Thomas McCarthy, 2015) On Camera Spotlight Team Robby Robinson Michael Keaton: Mr. Mom (83), Beetlejuice (88), Birdman (14) Mike Rezendes Mark Ruffalo: You Can Count on Me (00), The Kids Are All Right (10) Sacha Pfeiffer Rachel McAdams: Mean Girls (04), The Notebook (04), Southpaw (15) Matt Carroll Brian d’Arcy James: mostly Broadway: Shrek (08), Something Rotten (15) At the Globe Marty Baron Liev Schreiber: A Walk on the Moon (99), The Manchurian Candidate (04) Ben Bradlee, Jr. John Slattery: The Station Agent (03), Bluebird (13), TV’s Mad Men (07-15) The Lawyers Mitchell Garabedian Stanley Tucci: Big Night (96), The Devil Wears Prada (06), Julie & Julia (09) Eric Macleish Billy Crudup: Jesus’ Son (99), Almost Famous (00), Waking the Dead (00) Jim Sullivan Jamey Sheridan: The Ice Storm (97), Syriana (05), TV’s Homeland (11-12) The Victims Phil Saviano (SNAP) Neal Huff: The Wedding Banquet (93), TV’s Show Me a Hero (15) Joe Crowley Michael Cyril Creighton: Star and writer of web series Jack in a Box (09-12) Patrick McSorley Jimmy LeBlanc: Gone Baby Gone (07), and that’s his only other credit! Off Camera Director-Writer Tom McCarthy: See below; co-wrote Pixar’s Up (09), frequently acts Co-Screenwriter Josh Singer: writer, West Wing (05-06), producer, Law & Order: SVU (07-08) Cinematography Masanobu Takayanagi: Silver Linings Playbook (12), Black Mass (15) Original Score Howard Shore: The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (01-03), nearly 100 credits Previous features from writer-director