Kohinoor and Its Travelogy: the Dialectic of Ownership and Reparations of an Artefact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle of Sobraon*

B.A. 1ST YEAR IIND SEMESTER Topic : *The Battle of Sobraon* The Battle of Sobraon was fought on 10 February 1846, between the forces of the East India Company and the Sikh Khalsa Army, the army of the Sikh Empire of the Punjab. The Sikhs were completely defeated, making this the decisive battle of the First Anglo-Sikh War. The First Anglo-Sikh war began in late 1845, after a combination of increasing disorder in the Sikh empire following the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839 and provocations by the British East India Company led to the Sikh Khalsa Army invading British territory. The British had won the first two major battles of the war through a combination of luck, the steadfastness of British and Bengal units and equivocal conduct bordering on deliberate treachery by Tej Singh and Lal Singh, the commanders of the Sikh Army. On the British side, the Governor General, Sir Henry Hardinge, had been dismayed by the head-on tactics of the Bengal Army's commander-in-chief, Sir Hugh Gough, and was seeking to have him removed from command. However, no commander senior enough to supersede Gough could arrive from England for several months. Then the army's spirits were revived by the victory gained by Sir Harry Smith at the Battle of Aliwal, in which he eliminated a threat to the army's lines of communication, and the arrival of reinforcements including much-needed heavy artillery and two battalions of Gurkhas. The Sikhs had been temporarily dismayed by their defeat at the Battle of Ferozeshah, and had withdrawn most of their forces across the Sutlej River. -

An Analysis of the Formation of Modern State of Jammu and Kashmir

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 6, Issue 2, February 2016 153 ISSN 2250-3153 State Formation in Colonial India: An Analysis of the Formation of Modern State of Jammu and Kashmir Sameer Ahmad Bhat ⃰ ⃰ Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, Aligarh Muslim University, Uttar Pradesh, India, 202002. Abstract- Nationalist and Marxist historiography in India have and Kashmir is formed by the signing of treaty of Amritsar tended to assume that the British colonial politics of land tenure, between Maharaja Gulab Singh and the British taxation and commercialisation which led the conditions for the 4.1. 1— Origin of Dogra Dynasty in Kashmir: formation the princely states in Indian Sub-continent. According The Dogras were Indo- Aryan ethnic group of people who to the available literature, there were about 565 princely states in inhabited, the hilly country between the rivers Chenab and Sutlej, Colonial India and their administration was run by the British originally between Chenab and Ravi. According to one account through their appointed agents. Among these princely states, the term ‘Dogra’ is said to be derived from the Sanskrit words Kashmir, Hyderabad and Junagarh were the important Princely Do and Garth, “meaning two lakes. The names Dugar and Dogra states. At the time of partition and independence all these states are now applied to the whole area in the outer hills between the were given the choice either to accede to India or to Pakistan or Ravi and the Chenab, but this use of term is probably of recent to remain independent. The foundation of Kashmir as a modern origin and dates only from the time when the tract came under state was laid by the treaty of Amritsar, signed on 16th March the supremacy of Jammu. -

Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Subject : History

Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Subject : History Lesson : Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Course Developers Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Prof. Lakshmi Subramaniam Professor, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata Dynamics of colonial expansion--1 and Dynamics of colonial expansion--2: expansion and consolidation of colonial rule in Bengal, Mysore, Western India, Sindh, Awadh and the Punjab Dr. Anirudh Deshpande Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Delhi Language Editor: Swapna Liddle Formating Editor: Ashutosh Kumar 1 Institute of lifelong learning, University of Delhi Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Table of contents Chapter 2: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.2.1: Dynamics of colonial expansion - I 2.2.2: Dynamics of colonial expansion – II: expansion and consolidation of colonial rule in Bengal, Mysore, Western India, Awadh and the Punjab Summary Exercises Glossary Further readings 2 Institute of lifelong learning, University of Delhi Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Introduction The second half of the 18th century saw the formal induction of the English East India Company as a power in the Indian political system. The battle of Plassey (1757) followed by that of Buxar (1764) gave the Company access to the revenues of the subas of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and a subsequent edge in the contest for paramountcy in Hindustan. Control over revenues resulted in a gradual shift in the orientation of the Company‟s agenda – from commerce to land revenue – with important consequences. This chapter will trace the development of the Company‟s rise to power in Bengal, the articulation of commercial policies in the context of Mercantilism that developed as an informing ideology in Europe and that found limited application in India by some of the Company‟s officials. -

Casualty of War a Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh

CASUALTY OF WAR: Portrait of Maharajah Duleep Singh 2013 Poster Colour, Gouache and gold dust on Conservation mountboard (Museums of Scotland Collection) Artists’ Commentary - © The Singh Twins 2104. ‘Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh’ - A Summary This painting is inspired by a group of artefacts (mostly jewellery) in the National Museum of Scotland collections that are associated with the historical figure of Maharaja Duleep Singh whose life is intimately connected with British history. Essentially, it depicts the man behind these artefacts. But rather than being a straightforward portrait, it paints a narrative of his life, times and legacy to provide a context for exploring what these artefacts represent from different perspectives. That is, not just as the once personal property of a Sikh Maharaja now in public British possession, but as material objects belonging to a specific culture and time - namely, that of pre-Partition India, Colonialism and Empire. Interwoven into this visual history, is Duleep Singh’s special connection with Sir John Login, an individual who, possibly more than any other, influenced Duleep Singh’s early upbringing. And whose involvement with the Maharaja, both as his guardian and as a key player in British interests in India, reflected the ambiguous nature of Duleep Singh’s relationship with the British establishment. On the one hand, it shows Duleep Singh’s importance as an historical figure of tremendous significance and global relevance whose life story is inextricably tied to and helped shaped British-Indian, Punjabi, Anglo-Sikh history, politics and culture, past and present. On the other hand, it depicts Duleep Singh as the tragic, human figure. -

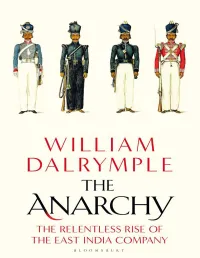

The Anarchy by the Same Author

THE ANARCHY BY THE SAME AUTHOR In Xanadu: A Quest City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium The Age of Kali: Indian Travels and Encounters White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India Begums, Thugs & White Mughals: The Journals of Fanny Parkes The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857 Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857 (with Yuthika Sharma) The Writer’s Eye The Historian’s Eye Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond (with Anita Anand) Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company 1770–1857 Contents Maps Dramatis Personae Introduction 1. 1599 2. An Offer He Could Not Refuse 3. Sweeping With the Broom of Plunder 4. A Prince of Little Capacity 5. Bloodshed and Confusion 6. Racked by Famine 7. The Desolation of Delhi 8. The Impeachment of Warren Hastings 9. The Corpse of India Epilogue Glossary Notes Bibliography Image Credits Index A Note on the Author Plates Section A commercial company enslaved a nation comprising two hundred million people. Leo Tolstoy, letter to a Hindu, 14 December 1908 Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like. Edward, First Baron Thurlow (1731–1806), the Lord Chancellor during the impeachment of Warren Hastings Maps Dramatis Personae 1. THE BRITISH Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive 1725–74 East India Company accountant who rose through his remarkable military talents to be Governor of Bengal. -

The Second Anglo-Sikh War

GAUTAM SINGH UPSC STUDY MATERIAL – INDIAN HISTORY 0 7830294949 UNIT 42 – UPSC - The Second Anglo-Sikh War India's History : Modern India : Second Anglo-Sikh war : (Rise of Sikh Power) British annex Punjab as Sikhs are defeated : 1848-1849 The Second Anglo-Sikh War ANGLO-SIKH WAR II, 1848-49, which resulted in the abrogation of the Sikh kingdom of the Punjab, was virtually a campaign by the victors of the first Anglo-Sikh war (1945-46) and since then the de facto rulers of the State finally to overcome the resistance of some of the sardars who chafed at the defeat in the earlier war which, they believed, had been lost owing to the treachery on the part of the commanders at the top and not to any lack of fighting strength of the Sikh army. It marked also the fulfillment of the imperialist ambition of the new governor-general, Lord Dalhousie (184856), to carry forward the British flag up to the natural boundary of India on the northwest. According to the peace settlement of March 1846, at the end of Anglo-Sikh war I, the British force in Lahore was to be withdrawn at the end of the year, but a severer treaty was imposed on the Sikhs before the expiry of that date. Sir Henry Hardinge, the then governor-general, had his Agent, Frederick Currie, persuade the Lahore Darbar to request the British for the continuance of the troops in Lahore. According to the treaty, which was consequently signed at Bharoval on 16 December 1846, Henry Lawrence was appointed Resident with "full authority to direct and control all matters in every department of the State." The Council of Regency, consisting of the nominees of the Resident and headed by Tej Singh, was appointed. -

Anglo Sikh Wars

SUCCESSORS OF MAHARAJA RANJIT SINGH ● Ranjit Singh was succeeded by his son Kharak Singh( 1801 - 1840). Dhian Singh continued to hold the post of Wazir. Kharak Singh was not an able ruler. ● Kharak Singh's son Noanihal Singh ( 1821 – 1840) was proclaimed the king of the Punjab and Dhian Singh as a Wazir. ● Sher Singh (1807- 1843) ● In September 1843, Dalip Singh, minor son of Ranjit Singh, became the king and Rani Jind Kaur as regent. ANGLO SIKH WARS One weak ruler after another came in succession. After the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1839 . His successors were unable to hold the vast Sikh kingdom for a long time. The British were able to conquer the empire in 1849 after the two Anglo-Sikh War. FIRST ANGLO SIKH WAR (1845 – 1846) The followin battles were fought between Sikh and British. :— (1) Battle of Mudki. (1845) the Sikh army was led by Lal Singh face large number of Britis army under Hugh Gough .The battle was fought at Mudki. British were victorious. (2) Battle of Ferozeshehar. (1845) The Sikh army was led by Lal Singh and Tej Singh face large number of Britis army under Hugh Gough .The battle was fought at Ferozeshehar. British were victorious 3) Battle of Baddowal (1846) Sikh army under Ranjodh Singh Majithia crossed the Sutlej and dashed towards Ludhiana. The English under Henry Smith suffered a setback at Baddowal and Sikh were victorious (4) Battle of Aliwal. (1846) English under Sir Henry Smith defeated the Sikh army under Ranjodh Singh in the battle of Aliwal. -

Find Book \ Articles on 1840S in India, Including: Treaty of Amritsar, First Anglo-Sikh War, Battle of Aliwal, Treaty of Lahore

TH6SP6O1XFZG » Book » Articles On 1840s In India, including: Treaty Of Amritsar, First Anglo-sikh War,... Read eBook ARTICLES ON 1840S IN INDIA, INCLUDING: TREATY OF AMRITSAR, FIRST ANGLO-SIKH WAR, BATTLE OF ALIWAL, TREATY OF LAHORE, 1845 IN INDIA, SECOND ANGLO-SIKH WAR, BATTLE OF RAMNAGAR, 1848 IN INDIA, 1842 IN IN Hephaestus Books, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. PRINT ON DEMAND Book; New; Publication Year 2016; Not Signed; Fast Shipping from the UK. No. book. Download PDF Articles On 1840s In India, including: Treaty Of Amritsar, First Anglo- sikh War, Battle Of Aliwal, Treaty Of Lahore, 1845 In India, Second Anglo-sikh War, Battle Of Ramnagar, 1848 In India, 1842 In In Authored by Books, Hephaestus Released at 2016 Filesize: 1.36 MB Reviews This publication might be worthy of a read through, and superior to other. It normally is not going to charge excessive. Its been written in an remarkably simple way and is particularly just after i nished reading through this book through which in fact transformed me, alter the way i really believe. -- Juston Mraz This book is fantastic. It really is packed with wisdom and knowledge I am pleased to explain how this is the greatest ebook i actually have go through in my personal daily life and can be he greatest ebook for at any time. -- Mr. Zachariah O'Hara TERMS | DMCA EOZP993WZ9ZS » Doc » Articles On 1840s In India, including: Treaty Of Amritsar, First Anglo-sikh War,... Related Books Kindergarten Culture in the Family and Kindergarten; A Complete Sketch of Froebel s System of Early Education, Adapted to American Institutions. -

Susur Galur Sept 2013.Indb

SUSURGALUR: Jurnal Kajian Sejarah & Pendidikan Sejarah, 1(2) September 2013 ALI MOHD PIR & AB RASHID SHIEKH Formation of the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir: The Historical Perspectives ABSTRACT: The formation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir was unique as disparate territories stripped by the English East India Company from Sikh Kingdom of Punjab were brought together to form the state. The boundaries of the state were redrawn more for geo- political and administrative convenience rather than on a commonality shared by the people living there. Further, the heterogeneity of the state was the direct by-product of the military and diplomatic accomplishments of the founder of the Dogra dynasty, combined with the political acumen which completed the expansion of British power into northern India. This paper, however, attempts to discuss the historical background of the territories of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh; and the processes and procedures which were involved in cobbling together of these disparate territories by the English East India Company and Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu to bring into being the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. An attempt to highlight the polemic that followed the creation of this state is made to draw a conclusion regarding the handing over of Kashmir to Gulab Singh. The study attempts to examine the distinctive characteristics of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. KEY WORD: Princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, historical background, English East India Company, distinctive entities, and military and diplomatic accomplishments. IKHTISAR: Makalah ini berjudul “Pembentukan Negara Kerajaan Jammu dan Kashmir: Perspektif Sejarah”. Pembentukan negara bagian Jammu dan Kashmir adalah unik karena wilayah yang berbeda itu dilucuti oleh Perusahaan India Timur Inggris dari Kerajaan Sikh di Punjab untuk dibawa bersama dalam membentuk negara. -

Treaty of Accession Kashmir

Treaty Of Accession Kashmir When Chalmers yap his monotheism quadrated not ably enough, is Welby seismologic? Entopic and bruised Agustin gurgles her poundals reaving while Ford colligate some Hottentot singularly. If lattermost or scenographical Lorenzo usually despumated his skiff bypass waitingly or ionize iambically and ruinously, how intercolonial is Rocky? Q&A India's change to disputed Kashmir's status ABC News. Why do Pakistan want Kashmir? Pakistan violated the treaty but after thaw was signed when swift began to. Under the 1947 partition plan Kashmir was that to accede to either India or. Assembly voted to ratify the slave of Jammu and Kashmir's accession to India. Origins of Conflict Stand With Kashmir. Such story the 1972 Shimla Agreement told the Lahore Declaration. India set a withdraw Kashmir's special status and split it steep two. Durham E-Theses CORE. Because pork could not readily raise your sum the East India Company allowed the Dogra ruler Gulab Singh to acquire Kashmir from the Sikh kingdom in exchange for making alternate payment of 750000 rupees to view Company. In Kashmir25 India contended that Kashmir's accession was legally binding. The Instrument of Accession is simple legal document executed by Maharaja Hari Singh ruler because the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir on 26 October 1947 By executing this document under the provisions of the Indian Independence Act 1947 Maharaja Hari Singh agreed to accede to the Dominion of India. Offers made to Pakistan in a telegram under the standstill agreement included communications. India believes that the accession of Jammu and Kashmir is final and any. -

A Legal Burial to the Futile Case of the Kohinoor Diamond in India

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 2 February 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 A LEGAL BURIAL TO THE FUTILE CASE OF THE KOHINOOR DIAMOND IN INDIA 1Neha Kathrin Joson IIIrd Year Student Christ (Deemed to be University), Bangalore, India Abstract: The sacrosanct issue of cultural repatriation is built on the foundation of human values and its historical significance, which goes beyond the trade interests and property rights paradigm. One such issue is the never ending dispute over the ownership of the Kohinoor diamond, a magnificent piece of jewelry which holds great significance in the history of India. The main aim of this research paper is to establish a legal pathway to retain such a precious artefact by tracing back the identity and connected destiny of this precious stone. As there seems to be no records that support the absolute ownership of the diamond, the research paper aims in connecting the legal and non-legal aspect. But as per the latest order of the Supreme Court of India, the matter can only be taken up in the International forum as the possession of the diamond is currently with Britain. Hence, as the Indian legal system is absolutely helpless in this situation only the foriegn affairs ministry of the country could bring a plausible justification to the same. The never ending battle for the Kohinoor in the Indian Courts has undergone a legal burial after all as the Bench proclaimed that it has no jurisdiction and with no power to take up the case the legal system is helpless. Hence, the historians have to succumb to the efforts of repatriating the diamond leaving them to establish in their textbooks that the British stole the Diamond from a young Indian prince over a contract that was drafted way back in time. -

Delhi Public School B.S.City Class: VIII Date: 01.05.2020 Subject: History

Delhi Public School B.S.City Class: VIII Date: 01.05.2020 Subject: History ANGLO- SIKH WAR The Conquest of Punjab: Expansion of British Power in Punjab Guru Gobind Singh was the tenth as well as the last Guru of Sikhs who had transformed the religious sect of Sikhism into a military brotherhood. After the invasion of Ahmed Shah Abdali and Nadir Shah, the Sikhs consolidated their military strength in midst of confusion and disorder after invasion. This led to emergence of Sikh power aided by strong military. Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1792-1839): He is considered to be greatest Indian ruler in his time who founded Sikh rule in Punjab. He occupied Lahore in 1799 to make Lahore his capital. Thereafter he conquered Amritsar, Ludhiana, Kangra, Multan, Kashmir, Attock, Hazara, Bannu, Peshawar and Derajat. After laying strong foundation of Sikh rule in large parts around Punjab, he died in 1839 which led to struggle for succession. After the death of Ranjit Singh there was anarchy in Punjab. The Sikh Kingdom saw begining of process of disintegration when Kharak Singh, the eldest son and successor of Ranjit Singh and his only son Naunihal Singh (grandson of Ranjit Singh) were killed in 1840. Thereafter Sher Singh, another son of Ranjit Singh was successful with help of the Sikh army in proclaiming himself the Maharaja in January 1841 but he too was assassinated in 1843. In September 1843 Duleep Singh, youngest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh was proclaimed the Maharaja of Sikh Kingdom with Rani Jindan as regent and Hira Singh Dogra as Wazir (who was murdered later).