A Conductor's Guide to Representative Choral Music Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swr2 Programm Kw 34

SWR2 PROGRAMM - Seite 1 - KW 34 / 23. - 29.08.2021 Montag, 23. August Frédéric Chopin: 8.58 SWR2 Programmtipps Mazurka f-Moll op. 68 Nr. 4 Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli 9.00 Nachrichten, Wetter 0.03 ARD-Nachtkonzert (Klavier) Carl Maria von Weber: Josef Mysliveček: 9.05 SWR2 Musikstunde „Oberon“, Ouvertüre Allegro assai aus dem Violinkonzert Leopold Mozart – Ein Mann mit Staatskapelle Dresden D-Dur EvaM 9a:D2 vielen Talenten (1) Leitung: Bernard Haitink Leila Schayegh (Violine) Der Augsburger Carl Loewe: Collegium 1704 Mit Bettina Winkler Streichquartett G-Dur op. 24 Nr. 1 Leitung: Václav Luks Hallensia Quartett Giovanni Battista Pescetti: Eugen d’Albert: Sonate Nr. 6 c-Moll Musikliste: Sinfonie F-Dur op. 4 Xavier de Maistre (Harfe) Emilia Giuliani: MDR-Sinfonieorchester John Field: Capriccio für Gitarre Leitung: Jun Märkl Rondo aus dem Klavierkonzert Nr. 7 Siegfried Schwab (Gitarre) Jan Dismas Zelenka: c-Moll Leopold Mozart, Wolfgang Sonate Nr. 4 g-Moll ZWV 181 Míceál O’Rourke (Klavier) Amadeus Mozart: Ensemble con bravura London Mozart Players 1. Satz: Allegro „Neue Lambacher Tom Tykwer: Leitung: Matthias Bamert Sinfonie“ aus: Sinfonie G-Dur KV „Cloud Atlas“, End Title Matthew Locke: Anh. 293 MDR-Sinfonieorchester Music for His Majesty’s Sackbuts The Academy of Ancient Music Leitung: Kristjan Järvi and Cornetts Leitung: Christopher Hogwood Philip Jones Brass Ensemble Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: 2.00 Nachrichten, Wetter Robert Schumann: Der Zauberer, Lied für Sopran und Finale aus Fantasiestücke op. 88 Nr. Klavier KV 472 2.03 ARD-Nachtkonzert 4 Juliane Banse (Sopran) Johann Sebastian Bach: Martha Argerich (Klavier) András Schiff (Klavier) Orchestersuite Nr. 1 C-Dur BWV Gidon Kremer (Violine) Hans Leo Haßler: 1066 Mischa Maisky (Violoncello) Cantate Domino, Psalmmotette für Café Zimmermann fünfstimmigen Chor a cappella, Sacri Antonín Dvořák: 6.00 SWR2 am Morgen Concentus (Augsburg, 1601) Slawische Tänze op. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

Table of Contents

Sheet TM Version 2.0 Music 1 CD Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven Major Choral Works Table of Contents Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, The Major Choral Works. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below or in the book- marks section on the left side of the screen to open the sheet music. Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find the score or parts of the work. Return to the table of contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Composers on this CD-ROM HAYDN MOZART BEETHOVEN The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 Music 2 CD FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART The Creation (Die Schöpfung) Veni Sancte Spiritus, K. 47 Part I Te Deum in C Major, K. 141/66b Part II Mass in F, K. 192 Part III Litaniae Lauretanae in D Major, K. 195/186d Mass No. 3 in C Major (Missa Cellensis) (Mariazellermesse) Mass in C Major, K. 258 (Missa Brevis) Mass No. 6 in G Major Missa Brevis in C Major, K. 259 (Organ Solo) (Mass in Honor of Saint Nicholas) Sancta Maria, Mater Dei, K. 273 Mass No. 7 in B Major b Mass in Bb Major, K. -

Beiträge Zur Lebensgeschichte Des Salzburger

© Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, Salzburg, Austria; download unter www.zobodat.at 179 Beiträge 3ur €ebensgefd)id)te 6cs Ga^burgct /5ofkapellmciftct5 Jobann £rnft £bedm Von M. Cuvay Lectori Benevolo Nobilis, ac Perdoctus Dominus Joannes Ernestus Eberlin Jettinganus Suevus, postquam in Gymnasio nostro Augustano classes inferiores omnes cum laude boni capacisque ingenii, egregiique profectus inter óptimos est emensus, inde ad Lyceum translatus, anno elapso Logicam inter primos, hoc vero Phisicam inter meliores absolvit, optimis haud dubie et hoc anno annumerandus, si magnae ingenii capacitad parem junxisset diligentiam et applicationem, ac musicae, cujus insigni pollet peritia, plus nimis non tribuisset. His ingenii, doctrinae, artisque Musicae dotibus junxit mores admodum obsequiosos, reverentes, civiles, Superiorumque, et Scholasticae dis* ciplinae observantes. Ita testor manu mea, et consulto Collegii nostri sigillo Augustae Vindelicorum die 19. Sept, anno a partu Virginis 1721. Georgius Kolb Soc. Jesu Lycei et Gymn. Praef. Auf deutsch: Dem wohlwollenden Leser. Der edle und sehr gelehrte Herr Johannes Eberlin, Schwabe aus Jettingen, ist — nachdem er in unserem Gym nasium in Augsburg alle Unterklassen mit der Anerkennung seiner guten umfassenden Intelligenz und seines hervorragenden Fortschritts unter den Besten durchlaufen hat — von dort an das Lyzeum versetzt worden und hat im vergangenen Jahr die Logik unter den Ersten, heuer aber die Physik unter den Besseren absolviert und wäre zweifellos auch in diesem Jahr den Besten zuzuzählen gewesen, wenn er zur großen Begabung seines Verstandes ebensoviel Fleiß und Ausdauer gesellt hätte, wie er sie nur allzusehr der Musik- widmete, in der er über eine gediegene Kenntnis verfügt. Mit dieser Ausstattung an Intelligenz, Wissen und musikalischem Können vereinte er ein Betragen voll großer Dienstwilligkeit, Ehrerbietung und Höflichkeit und voll Hochachtung vor seinen Vorgesetzten und der Schule mit ihrer straffen Zucht. -

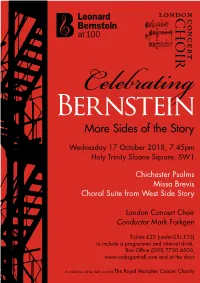

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door A collection will be held in aid of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Music Director: include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all Mark Forkgen ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut Nathan Mercieca from the score of the musical. countertenor In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in Richard Pearce medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for organ The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, countertenor soloist and percussion. Anneke Hodnett harp After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Sacha Johnson and West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Alistair Marshallsay America and Somewhere. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven Franz Schubert Wolfgang

STIFTUNG MOZARTEUM SALZBURG WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 FRANZ SCHUBERT SYMPHONY NO. 5 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART PIANO CONCERTO NO. 23 ANDRÁS SCHIFF CAPPELLA ANDREA BARCA WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Vienna - once the music hub of Europe - attracted all the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 greatest composers of its day, among them Beethoven, Schubert and Mozart. This concert given by András Schiff and FRANZ SCHUBERT the Capella Andrea Barca during the Salzburg Mozart Week Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, D 485 brings together three works by these great composers, which WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART each of them created early in life at the start of an impressive Piano Concerto No. 23 in E flat major, KV 482 Viennese career. The programme opens with Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto: Piano & Conductor András Schiff “Sensitively supported by the rich and supple tone of the strings, Orchestra Cappella Andrea Barca Schiff’s pianistic virtuosity explores the length and breadth of Beethoven’s early work, from the opulent to the playful, with a Produced by idagio.production palpable delight rarely found in such measure in a pianist”, was Video Director Oliver Becker the admiring verdict of the Salzburg press. Length: approx. 100' As in his opening piece, Schiff again succeeded in Schubert’s Shot in HDTV 1080/50i symphony “from the first note to the last in creating a sound Cat. no. A 045 50045 0000 world that flooded the mind’s eye with images” Drehpunkt( Kultur). A co-production of The climax of the concert was the Mozart piano concerto. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Beethoven to Drake Featuring Daniel Bernard Roumain, Composer & Violinist

125 YEARS Beethoven to Drake Featuring Daniel Bernard Roumain, composer & violinist TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE 87TH Annual Young People’s Concert William Boughton, Music Director Thank you for taking the NHSO’s musical journey: Beethoven to Drake Dear teachers, Many of us were so lucky to have such dedicated and passionate music teachers growing up that we decided to “take the plunge” ourselves and go into the field. In a time when we must prove how essential the arts are to a child’s growth, the NHSO is committed to supporting the dedication, passion, and excitement that you give to your students on a daily basis. We look forward to traveling down these roads this season with you and your students, and are excited to present the amazing Daniel Bernard Roumain. As a gifted composer and performer who crosses multiple musical genres, DBR inspires audience members with his unique take on Hip Hop, traditional Haitian music, and Classical music. This concert will take you and your students through the history of music - from the masters of several centuries ago up through today’s popular artists. This resource guide is meant to be a starting point for creation of your own lesson plans that you can tailor directly to the needs of your individual classrooms. The information included in each unit is organized in list form to quickly enable you to pick and choose facts and activities that will benefit your students. Each activity supports one or more of the Core Arts standards and each of the writing activities support at least one of the CCSS E/LA anchor standards for writing. -

The Critical Reception of Beethoven's Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op

The Critical Reception of Beethoven’s Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op. 124 Translated and edited by Robin Wallace © 2020 by Robin Wallace All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-7348948-4-4 Center for Beethoven Research Boston University Contents Foreword 6 Op. 123. Missa Solemnis in D Major 123.1 I. P. S. 8 “Various.” Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 1 (21 January 1824): 34. 123.2 Friedrich August Kanne. 9 “Beethoven’s Most Recent Compositions.” Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung mit besonderer Rücksicht auf den österreichischen Kaiserstaat 8 (12 May 1824): 120. 123.3 *—*. 11 “Musical Performance.” Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode 9 (15 May 1824): 506–7. 123.4 Ignaz Xaver Seyfried. 14 “State of Music and Musical Life in Vienna.” Caecilia 1 (June 1824): 200. 123.5 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of May.” 15 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 26 (1 July 1824): col. 437–42. 3 contents 123.6 “Glances at the Most Recent Appearances in Musical Literature.” 19 Caecilia 1 (October 1824): 372. 123.7 Gottfried Weber. 20 “Invitation to Subscribe.” Caecilia 2 (Intelligence Report no. 7) (April 1825): 43. 123.8 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of March.” 22 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 29 (25 April 1827): col. 284. 123.9 “ .” 23 Allgemeiner musikalischer Anzeiger 1 (May 1827): 372–74. 123.10 “Various. The Eleventh Lower Rhine Music Festival at Elberfeld.” 25 Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 156 (7 June 1827). 123.11 Rheinischer Merkur no. 46 27 (9 June 1827). 123.12 Georg Christian Grossheim and Joseph Fröhlich. 28 “Two Reviews.” Caecilia 9 (1828): 22–45. -

Antonio Salieri's Revenge

Antonio Salieri’s Revenge newyorker.com/magazine/2019/06/03/antonio-salieris-revenge By Alex Ross 1/13 Many composers are megalomaniacs or misanthropes. Salieri was neither. Illustration by Agostino Iacurci On a chilly, wet day in late November, I visited the Central Cemetery, in Vienna, where 2/13 several of the most familiar figures in musical history lie buried. In a musicians’ grove at the heart of the complex, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms rest in close proximity, with a monument to Mozart standing nearby. According to statistics compiled by the Web site Bachtrack, works by those four gentlemen appear in roughly a third of concerts presented around the world in a typical year. Beethoven, whose two-hundred-and-fiftieth birthday arrives next year, will supply a fifth of Carnegie Hall’s 2019-20 season. When I entered the cemetery, I turned left, disregarding Beethoven and company. Along the perimeter wall, I passed an array of lesser-known but not uninteresting figures: Simon Sechter, who gave a counterpoint lesson to Schubert; Theodor Puschmann, an alienist best remembered for having accused Wagner of being an erotomaniac; Carl Czerny, the composer of piano exercises that have tortured generations of students; and Eusebius Mandyczewski, a magnificently named colleague of Brahms. Amid these miscellaneous worthies, resting beneath a noble but unpretentious obelisk, is the composer Antonio Salieri, Kapellmeister to the emperor of Austria. I had brought a rose, thinking that the grave might be a neglected and cheerless place. Salieri is one of history’s all-time losers—a bystander run over by a Mack truck of malicious gossip. -

Missa Brevis

Jacob de Haan Missa Brevis Partiture per coro misto Solo per uso personale 2 Ⓡ Ⓡ Soli Deo Hon Et Gl ia 3 Missa Brevis Indice dei contenuti Kyrie .............................................. .............. 4 Gloria............................................. ............... 6 Credo.............................................. .............. 11 Sanctus ............................................ .............. 18 Benedictus......................................... ................ 20 Agnus Dei .......................................... ............... 24 4 Missa Brevis Kyrie Coro Misto Jacob de Haan ø = 80 Soprano 11 2 2 Ky ri e e lei son, Ky ri e e lei son, f f Alto 11 2 2 11 Tenore 2 8 2 Kyf ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son, 11 Basso 2 2 19 S 3 Ky ri e e lei son, Ky ri e e lei son, 2 f f A 3 2 T 3 8 2 Kyf ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son, B 3 2 28 S 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 Ky ri e e 2 lei son, 2 Ky ri e e 2 lei son. 2Christe e 2 lei son, 2 ff f p A 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 T 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 8 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Kyff ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son. Chrip ste e lei son, B 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Coro Misto 5 34 S 3 2 3 2 2 Christe e 2 lei son, e lei son, 2 Chri ste Chri ste 2Christe e A ff ff ff 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 T 3 2 3 2 8 2 2 2 2 Christe e lei son, e lei son, Chriff ste Chriff ste Chriff ste e B 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 41 S 2 2 3 2 3 lei son. -

Oratorios by Amandus Ivanschiz in the Context of Musical Sources and Liturgical Practice1

MUSICOLOGICA BRUNENSIA 49, 2014, 1 DOI: 10.5817/MB2014-1-15 MACIEJ JOCHYMCZYK ORATORIOS BY AMANDUS IVANSCHIZ IN THE CONTEXT OF MUSICAL SOURCES AND LITURGICAL PRACTICE1 Fr. Amandus Ivanschiz was most likely born on December 24, 1727 which was the day he was baptized in Wiener Neustadt (Austria), with the names of Mat- thias Leopold.2 In December 1743 he entered the Pauline Order and took the name Amandus. After receiving his Holy Orders, the years 1751–54 he spent in Rome, where he served as a socius of the Procurator General of the Order. Soon after his return, in 1755, Ivanschiz was moved to the Maria Trost monastery near Graz, where he died in 1758, in the age of merely thirty-one. About one hundred compositions by Fr. Amandus have come down to us. His oeuvre includes both instrumental works, and vocal-instrumental sacred music. Apart from numerous manuscripts of doubtful attribution, the firs group comprises about 20 sympho- nies and 13 string trios. The second group is more extensive, and contains 17 masses, 13 litanies, 7 Oratorios, 9 settings of Marian antiphons, 8 arias and duets to non-liturgical texts, as well as vespers and Te Deum. Many of these works have survived in a few or even a dozen or so copies, which are now found in many, mainly Central European countries, such as Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Re- public, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden and Switzerland. It proves that Father Amandus’ music was known to a wide audience and places him among the most popular monk-composers of the 18th century.